US-Canadian Border to Blairemore

July 8, 2004

Kristine is gone, and I have no more ties, no more deadlines, no people to meet. A few tourists mill about downtown Waterton, but the wind is high and cold and the main tourist season is still a few weeks away. Summer comes late to the Rockies. Unsure of what to do with myself, I do the only thing possible. I sit.

Kristine and I made the short walk out to the border for some obligatory pictures earlier in the day. The border, like that at Manning Park, has little of interest. Like Manning Park, there is a small replica of the Washington Monument and stone pillar with a few words of wisdom. A trail sign indicates that the trail to the south is the Continental Divide Trail, the American, and more established, version of the GDT. A boat load of tourists float by on the lake, no doubt irked that we will appear in their border pictures. There isn't much reason to linger, especially in the cold wind.

Which brings me back to Waterton and my lack of anything to do. I sat alone for only a few minutes before a strong, tanned man with shoulder length blonde hair walks up and introduces himself as James. Without a doubt, he is a hiker or climber or some sort of outdoors person. We chat for a few minutes and he abruptly invites me to dinner, his treat. He is a chef in one of the restaurants in Waterton and spends most of his free time climbing and fishing in the area. Very craftily, we sneak ahead of the long line of waiting patrons at one of the restaurants by asking to sit outside. After ordering a couple of beers and some dinner, James then asks if we could move inside where it is warmer. Sipping on our beers, the conversation begins to get slightly strange. James becomes confused and surprised when I am able to use the metric system. He gets highly agitated when I mention the American ban on importing Canadian beef, despite the fact that we both disagree with Bush's policy on this. He seems to think that the US tariff on softwood lumber is actually benefitting the Canadian market. The subject of Iraq comes up, and genuine rage flares in his eyes, again despite the fact that we both disagree with the official US policy. I try to explain to him that I do not feel anger or hatred toward my leaders, but rather pity and sorrow. His expression changes instantly and the conversation moves toward a more philosophical one. James finishes another beer and orders another. I'm starting to worry that he might not have the best of intentions toward me, but am determined to stay and find out.

Our bout of philosophy over, he becomes frightened when I assert that there will be some sort of terrorist attack in the United States before the election. This seems to be fairly logical, given that there was a large attack in Madrid just before the Spanish elections. James asks me if I am a terrorist. A little unsure of how to respond, I try the simple approach and just say no. He asks again, and I tell him no again. "You're not going to kill me, are you? I mean, you won't stab me with a knife or anything like that, will you?" I hear the words and push a french fry into a bit of ketchup on my plate. I'm again taken aback by the directness of James' questions. Again, I opt for the simple approach and tell him no. James seems much relieved by my response. "What are you running away from?" Thinking that he means some sort of metaphysical running, I ponder the questions for a moment, and tell him that I am running away from nothing. Rather, I am trying to run toward something. This, he does not believe for a moment and demands that I answer him while looking at him. I repeat my answer, staring straight at him. Still, he seems to think this odd. "Parents? Girlfriend? Boyfriend?" I grasp immediately that he was not trying to be philosophical with his question. Rather, he quite literally thought I was a runaway. I chuckle when I realize that all along he thought that I was running away from my home or from some bad relationship. That my picture was on the side of a milk carton somewhere. After all, what could someone with a pack be doing in Waterton?

After assuring James that I was indeed going on a long walk to the north, we finish our beers and part ways. I look back to make sure James left the right amount of money on the table, as initally he was short by $10. The waitstaff nod when I point to the money and, satisfied, I set out to find a place to stay for the night. Walking through town toward the lake, I pass through the entrance to the campground without giving them attendant the $19 for the night. He doesn't bother to ask, and I don't bother to tell. At the far end, right on the lake and exposed to the full force of the strong winds blowing in from the US, is situated a patch of rolling grass that is meant for hikers and bikers. A three sided picnic shelter is right next to the bear lockers (only 1/3 of which actually latch closed) and I decide to spend the night in there, instead of in my tarp exposed to the howling wind. An American cyclist from Colorado, out on a long loop from home, is in the site as well, although he has put up his tent, which sits flapping in the wind. We talk briefly until the sun goes down, at the ridiculously late hour of 10, at which point we adjourn to our respective homes for the night. After putting the final touches on today's journal, I read the first few pages of the Dhammapada, a Buddhist text that I am carrying with me for the first half of the trek. I don't get much further than the introduction before sleep begins to overcome me. The live-wire feeling that I had before beginning the PCT last year is gone, but excitement still courses through my veins. It is a different kind of excitement. Serenity mingles with joy. There are no doubts, no worries, no concerns. I look forward to tomorrow when I'll first climb into the mountains, knowing that grand scenery is ahead, knowing that I have more than a thousand kilometers of adventure ahead of me, knowing that the Unknown Future is to be neither feared nor brooded upon . The Way is clear and everything will work itself out in time, as long as I let it.

Morning begins early this far north, and I roll out of my sleeping bag into the cold air to find clear skies, and the ever-present howling wind. My watch reads 5:30 am, and it is completely light. I pack up most of my stuff, not wanting to have appeared to have slept in the shelter (which is technically illegal), and begin to brew some tea. I don't have a long walk today and there is no hurry to leave town. No hurry, that is, except for my desire to get into the mountains again. Because of the restrictive Parks Canada system, I have to camp only in designated campsites. I've decided to try an alternate route tomorrow, and a short 25 K day will get me into Akamina-Kishinena Provincial Park, near the start of the alternate route. As it is located in British Columbia, and as I am currently in Alberta, I will cross the Continental Divide for the first time today. Sipping on tea, I pour over the massive stack of maps that I have brought with me. Covering the entire trail corridor from here to the hamlet of Field, near Banff townsite, I've never carried such a swath of land on my back. My tea done, I pack up the rest of my gear and am ready to leave when the Coloradan cyclist emerges from his tent and invites me to coffee. We talk about our various trips and he laments the fact that he doesn't have the time to go further north than he can on this trip. He also laments the fact that he is on a bike, reasoning correctly that one can see more on foot on a trail than from a bike on a road. I counter with the fact that, as he is on a bike, he can see a wider variety of land in a shorter amount of time than I can on foot. I don't completely believe this argument, but for someone with two weeks of vacation time a year, it seems sensible. Coffee finished, I wish him well on his journey and head into town for breakfast.

Cafe Franks advertises various breakfast specials along with Chinese food. I order one of the specials, which consists of two sausages, two strips of bacon, two eggs, and two pancakes. I add an order of hashbrowns and coffee and relax with the morning paper. The place was empty when I came in, but slowly begins to fill, first with people obviously getting ready to set out on some sort of day trip, then with older RV types, and finally with corpulent tourists. I've been sitting and drinking coffee for quite some time, as the paper is long. Finally, it is time to start walking north. Stepping outside, I am surprised by how much the morning has warmed. Barely above freezing when I awoke, the air has warmed to a comfortable fifty degrees, with clear skies and a warm sun. I move leisurely through town looking for the trailhead that will take me up into the hills. I stop and linger by the shore of the deep blue lake, thinking of nothing in particular. My stop becomes drawn out as I stand by the shore and simply be.

The spell is broken by the rattle of a large diesel pickup truck, hauling around someone's summer home, driving down the main town road. Setting off, again, I miss the trailhead and climb up various use trails to no where in particular, before cutting cross country to get to the true trailhead. Thirty minutes have gone by, and I am no further north, but this does not seem to me to be wasted time. The sun is shining and the air is warm, and I am in no rush.

Beginning in low forest, the trail climbs in earnest toward Alderson lakes and the alpine. While steeper than the average grade of the PCT, it is gentler than the grade of the Appalachian trail. Having hiked more than 1100 miles on the AT before beginning the GDT seems to have been wise from a fitness perspective. Of course, the hills on the AT are generally lower and it is rare for a climb to ever take more than 40 minutes. It takes me an hour and a half to reach the turn off for Alderson lakes. Declining to walk to them, I decide to take a break by the trail sign. A deer promptly walked into the area, not overly concerned with my presence, in search of something good to eat. I was still in the trees, but it was clear that I would not be for very long. The evergreens were getting shorter and thinner and the stands more spaced out. I caught the smells of the alpine that drifted down from above and knew that treeline was not far off. Saying good-bye to the deer, who was now in the forest a few meters to my left, I began to climb again, with a renewed pace. Not five minutes later, I leave the trees for good and stare down at the shimmering blue-green of Alderson lake.

Sitting at the base of the mountain that I was now skirting, Alderson lake is about as scenic as it is possible for a lake to be. The trees are gone, replaced with low lying vegetation and rock. I could be back in the Sierras. My spirit lifts up and begins to soar on the wind, joining the hawks above me. Everything feels so right, despite the sweat running down my face and neck and the panting of my breath. After forty eight days on the AT, I needed to return to the hills. I needed to be in a place like this, at a time like this. The only trace of humanity is the trail that I am on. The constant road sounds and hum of electricity on the Appalachian trail is gone. The (relative) swarms of hikers are gone. Shelters are gone. White blazes and blue blazes are gone. There is no trail purity or dogma.

The trail climbs up to a ridge, passing through a few small snowbanks, and then flattens out while skirting Carthew lakes, even more scenic than Alderson. Unfortunately, the Canadians do not allow camping here. Given the alpine conditions, it is probably for the best. Climbing once again on snow, I lose the trail occasionally, but this doesn't seem to matter much to me. I can see where I need to go, and so just go. The snow runs out and I regain the trail for the final push up to Carthew Summit, which is more like a mountain pass than a peak. I can see several day hikers huddled around the pass, trying to hide from the cold wind. My steps become slower and my breath heavier as I struggle with the steepening grade. The trail I'm following climbs above the pass and the descends on a snow bank to the pass itself. Although use trails take a more direct route, I stay on trail, if for no other reason than that people are watching me. Arriving at the pass, I'm stunned by the view. I've been in some beautiful places in my short life, but still Carthew summit amazes me. Three hundred sixty degree view. The towering mountains to the south in Glacier National Park in the US. To the east, the powerful mountains I had come through drop off into the plains that make up most of Alberta.

To the north and west, pile upon pile of mountains that I will have to (as if this is a bad thing) traverse on my way to Robson. The emerald lakes that sit at the base of glaciated mountains dot the landscape. The brown and tan of a land of mountains in a rain shadow contrast with the lush green of the ones that form the rain shadow. The Spectrum Range. The Khumbu. Death Valley in the early morning. A sunset in the Syrian desert. Now, Carthew summmit. I'm as stunned as the day hikers and none of us offer up even a greeting. Preferring the howl of the wind and the sights around us to the companionship of yet another human.

I sit for thirty minutes before I finally say hello to the day hikers. They had come up from the Cameron lake, where I was heading, as the distance is much shorter than coming from Waterton. A woman among them seemed to have hiked quite a bit in the area and offered some dire warnings for the alternate route that I was planning. She seemed to think that the ridge connected Mount Rowe to Lineham ridge was difficult at best. I was not worried, as I was not planning to take the ridge to Lineham, but instead stay on the crest all the way to Sage Pass and the end of Waterton park. Thanking her for her advice and the information, I left them to begin the long switchbacked descent to Cameron lake. For thirty minutes I slowly descended, battered by the high winds that raged unchecked by the lack of trees, along the side of the mountain. I was actually happy to regain the trees and get a respite from the winds. I passed one, two, three groups of day hikers coming up from Cameron lake, all looking to be in various stages of exhaustion. I continued to thump down the trail, now off the exposed side of the mountain, and reached the bottom to find throngs of tourists out on the lake. It could have been the Appalachian trail all over again. In fact, it was just as bad as the hordes at Bear Mountain in New York. Although tired from my exertions, I couldn't stop at the lake. It was just too much after the relative isolation and grandeur of the morning and early afternoon. I straggled out onto the road, passing by the first car I'd ever seen with license plates from the Northwest Territories, and began the several kilometer walk to the trail into Akamina-Kishinena. Surprisingly, the road was much more open and relaxing than Cameron lake. Few cars passed me and the kilometers went by quickly. I was, however tired by the time I reached the trail and did not like the idea that I was going to have to climb over Akamina Pass. I rested and looked at my map again, hoping that the pass would not be very high. I was relieved to find it less than a hundred meter climb up, spread out over several kilometers.

Still feeling tried, I began the haul to my campsite for the night, in Akamina-Kishinena provincial park. British Columbia has a standardized system for camping in its provincial parks: Pay $5, no reservations. It seemed much more civilized than the Parks Canada system for the national parks. I shuffled along until reaching the turn off where I would try the alternate route up Mount Rowe, where the paybox for the campsite was also located. I filled out the registration form and dropped $5 into the box before exploring up the alternate route. There was a rough use-trail leading past the monument marking the border between British Columbia and Alberta and it looked reasonable: Slightly overgrown, but nothing bad. Returning to the paybox, I shouldered my pack and walked down to the campsite, situated along a small creek. Two large tents were already in place, but their occupants were nowhere to be seen. I put up my tarp in a rock hard campite next to the tattered remains of a building. A sign warning not to camp in the building seemed rather comical at the time, as even the base of a tree would offer better weather protection.

My camp set, I moved to the cooking area, which had the obligatory bear boxes and a stack of firewood that the provincial rangers had chopped for use by campers. How nice! The bear boxes even latched properly, unlike those in Waterton. I made some tea before dinner and looked over my maps and the guidebook to familiarize myself with my route. It looked challenging, but very exciting as well. I started water boiling for my dinner of kimchi ramen when the other campers returned from fishing at one of the local lakes. Two father-son teams, they rode up on mountain bikes, the three kilometers out to the road being too much to walk. They had an interesting mix of car-camper mentality with backpacker gear. The car camper mentality told them to cook up their fish right in camp and toss the innards and heads into a plastic sack on the ground. I didn't bother with a lecture about attracting bears, despite the fact that one of the father's told me that bears were common in the area. The backpacker gear meant that they had to cook the fish over one small backpacking stove that could not simmer. The result was a lot of burnt fish, despite the copious amounts of butter they used. Still, they were very friendly and I enjoyed talking with them quite a bit. One of the fathers had hiked in the Lineham ridge area and warned me that it was very rugged with a lot of exposure. Both fathers seems intrigued by my trip and wished they had the time off to do something like that some day. It was always some day, never today, it seemed.

As the temperature began to drop, I retired to my tarp and the Dhammapada. A light rain began to fall and the tarp began to sag. Made of silicone impregnated nylon, or silnylon, the tarp was taught when I pitched it. Silnylon stretches slightly when it gets wet or damp and needs to be restaked. I was too tired to be bothered with getting out of my sleeping bag. It was still completely light out when I began to drift off to sleep at nine. No sunset, no stars. Only the light patter of rain on the tarp and the anticipation of tomorrow. I would always remember today's hike, not only because of the spectacular land it traversed. I would remember it as the first steps on my adventure. It was not happening some day. It was right now, right here.

It rained lightly on and off during the night, and was still raining when I woke up. The tarp was sagging quite a bit and I had to be careful getting out of my sleeping bag without touching the wet-with-condensation walls. Donning my rain jacket, I walked through the rain to the bear boxes to retrieve my food and cookpot. A cold morning made worse by the wet demanded that tea be had before moving on. I restaked the tarp so that it was taut and quickly set about making tea and eating breakfast. The rain stopped, for the moment, and, breakfast and tea finished, I took the opportunity to pack up. The father-sons teams were still asleep when I began walking at the incredibly late hour of 7:30 am. Although it never rained hard, it had rained long and the vegetation was heavy with water. My hopes for the alternate route were soon dashed. While the use-trail past the monument was good initially, it quickly degenerated after passing by a weather station that was monitored by the provincial rangers. Swamps began the difficulty, vegetation finished it. Everything was hanging over the route I was trying to take, soaking me to the bone as quickly as if it was actually raining. I could see the cut line easily by looking up at the gaps in the trees. But, down at my level, everything was thick and tangled. Dejected, I decided not to fight nature and instead to return to the road and walk it a bit further north so that I could take an actual trail up to Lineham ridge and the interesting sounding Tamarack summit.

I found the road walk quite enjoyable, as there were few cars out this early in the morning, the weather was improving, and the sights from the road good. By the time I reached the trailhead for the Tamarack trail, the weather was looking positively delightful, with patches of clear blue showing through the slate gray sky. A few day hikers were milling about, looking uncertain. Perhaps they were worried about the weather or waiting for others. I started up the trail into the woods, gaining elevation slowly. Better graded, and with more switchbacks than yesterday, the Tamarack trail worked its way slowly up the hillside, running straight up a valley toward Lineham ridge. Mountains appeared here and there through the trees as I climbed higher and higher.

Finally breaking through the trees, the trail swung to the south to enter a large meadow at the base of a cirque. A pleasant stream meandered through the green grass. Powerful mountains thrust up above, forming the walls of a cirque. To go any further, I was going to have to do some work. I found a middle aged couple with a dog sitting by the log bridge over the stream and decided to sit and have a break with them before starting to climb. The couple pointed out some hikers nearing the crest of the cirque, far above, their outlines visible, just barely, again a patch of white snow.

The couple had recently gotten married at Bertha Lake, which Kristine and I had passed on our walk out to the border. They had known each other for years, but were only recently married. I thought their choice of marriage hall to be a good one indeed. The man had been exploring in the area for years and had nothing but good things to say about the route to the north. He didn't have to add that he would like to do it some day. He had been doing things like it for decades, for longer than I was alive.

Feeling refreshed, I started the steep climb up to Lineham ridge and Tamarack summit. Although tiring, I knew the rewards would be great. Indeed, I quickly left the trees behind and was again ensconced in the alpine. Passing one snow back after another, the trail gained elevation without the aid of switchbacks as it traverse along the wall of the cirque. Not until I was well past the small gap that I was shooting for did the trail start to switchback and work its way back to the gap. Higher I climbed, with better and better views down into the valley I had just come up.

With sweat pouring off of me, I finally reached the top of the ridge and began the traverse to the gap, and eventually Tamarack summit, a clump of rock fifty meters above. The mountains forming the cirque that I had climbed out of loomed large, and the route that the day hiker yesterday had warned me about seemed very precarious.

With the last bit of strength I had, I finished the climb to Tamarack summit, only to find the two hikers I had spotted from below lazing about. Not wanting to disturb them and wanting to enjoy the area by myself, I walked off the top of the summit and back onto the ridge that I was to run for a kilometer or so. A few meters past the hikers, I sat on the lee side of a large rock to get out of the cold wind. Even with a bright sun and few clouds, it was cold in the wind and I was wet with sweat. As with Carthew summit yesterday, I again found myself in the midst of the most beautfiul place in the world. At least, the most beautiful right now.

I was reminded heavily of the Sonora pass area on the PCT, where the trail takes an adventurous route along a ridge crest for many miles of treeless hiking. Here, the same thing was happening. There is something very pleasing about being in a high place with views measured in the hundreds of miles. The mountains of northern Montana were clearly visible as were the plains of eastern Alberta. Everywhere I looked suggested some fun place to go. Some day, I thought, maybe I would do something like that, but for now I've got my own trip to Mount Robson to take joy in. I sat in the sun and the calm provided by the rock for some time. Day hikers would be going no further, as the closest road in the direction I was going was too far for them to reach. There were no backpackers behind me. I had the place to myself and was not pressed for time. Again, Parks Canada's camping policy was going to force me to end my day early. This, I suppose, was a good thing as my body was beginning to tire anyways. I eyed the route I had been planning to take and it looked very feasible. I was on the ridge on one side of a valley, down into which I must eventually go. On the other side of the valley was the alternate ridge, up to which I would eventually have to cliimb. Few trees and no cliffs seemed to offer much obstuction to cross country hiking, and as beautiful as the climb up here was, I wished I was on the other side.

My ridge ended after a kilometer, or so, or, rather, the trail dropped off of it and began to switchback steeply down into the valley below. Regaining the trees meant a loss of views, but also protection for the wind. There always seemed to be a tradeoff between comfort and views, and now I was in the comfort zone.

The trail ran to one side of the valley and switchbacked up, unexpectedly, the hillside, before dropping down steeply to reach a crossing of a stream. Gathering clouds convinced me to take a break and dry some of my gear while I had the sun to do it. Munching on Nutella burritos, the stream proved to be a nice place to rest and I dawdled for nearly an hour before deciding that it might be good to get to camp before the rains came. I climbed up a very steep section of trail to reach a pass over looking a scenic lake, barely pausing for the sight before dropping steeping down the other side and back into the trees.

The sky was turning gray, even black in places, and it seemed that rain was imminent. I ran into two women on horses heading in the opposite directions, and stopped long enough to find out that it was not going to rain for a couple of hours at least. How they knew this, I do not know. But, they were local to the area and probably had a better knowledge of the local weather patterns that I did. I pushed on for Twin lakes, hoping they were right. The rumble of distant thunder could be heard, and I quickened my step. I pushed up hard to the final pass, topping out with a gorgeous panorama of the Twin Lakes. The lower lake had the prototypical glacial lake appearance: Small, deep emerald-blue, silty. The upper lake appeared dark and mysterious. Somewhere by it was the campground I was gunning for. Above the lakes towered the ever present grey mountains holding columns of snow in various gullies. I stopped. I paused. I didn't bother to sit or take off my pack. Places like this are the goal of every one who has ever set foot in the outdoors. Places of such beauty that you can lose yourself in simple sensory splendor. Places that feel so right that nothing needs to be said, nothing needs to be pointed out. Twin Lakes is a place everyone should go, Some Day.

I trotted down from the pass and along the mountain side, stopping to pick up a full water bag from a freshet coming off the mountain above. Lake water is almost universally bad and I didn't want to have to walk back here from camp. The campsite had the same hard tent pads as in Akamina-Kishinena, and as before I had company. Three groups of backpackers had come in via the much shorter, and according to them not-very-scenic, Snowshoe trail. A fourth group came in as I set up camp. This is one of the problems with not allowing random camping: In an attempt to control where people camp, the system destroys much of the solitude that Parks Canada states is one of its goals. Still, the backpackers were all fun to be around and several of them were veterans of various treks in Nepal, which gave us much in common. They were all excited about my trip, and two German women had just returned from Jasper. They were at the end of a trip in the US and Canada and gave me some information about the upcoming (in the far future) restrictions on permits (not that I intended to permit the restrictions to affect my trip). I had just finished cleaning up from another dinner of kimchi ramen when the skies opened up and it began to rain slightly. I hung my food and retired to my tarp, which I restaked in an attempt to keep it taut. The Dhammapada came out once more, although the day's exertions had tired me to the point that I could read only a few pages before beginning to drift off. Again, it was past 9 pm and it was completely light out. Last summer on the PCT I always had the sunset and the stars to look forward to at the end of the day. Now, I had only hard tent pads and a grey tarp.

The rain tapered off over night and I awoke to a mostly blue, very cold sky. I retrieved my food and hopped back into my sleeping bag while my morning tea was brewing. The Oatmeal-To-Go bars that I had bought in Calgary for breakfast were quite solid, and so I sat them on top of the pot to warm while I looked through the guidebook. It seemed like a difficult day was in front of me. Directly above Twin Lakes is Sage Pass and the end of Waterton National Park. This also meant the end of good, reliable trail. Later in the day I would leave trail completely for what Dustin Lynx, the guidebook author, described as a "bold segment." Phrases like "faint trail" and "extremely strenuous" and "sparse water" popped up now and then. It seemed like getting cliffed out on LaCoulotte peak was highly probable. To be blunt, I was a little scared. The confidence that I had only two days ago about the Unknown had largely vanished. And I hadn't even left my tarp yet.

I quickly gulped down the tea for warmth, drawing some confidence from the caffeine, and ate the now warm oatmeal bars. The icing had melted slightly, given them a gooey, fresh baked texture. No one was stirring in the camp when I left 7:15. High above me, small puffy clouds were racing by at an extraordinary pace. Wind. High wind. I pushed up to Sage Pass, where a marker indicated that I was leaving the park, and the trail began to thin. A blast of wind met me, though this abated as I followed the faint trail through the woods. Although it faded out at times, I was knew that I had to go up hill and climb a ridge. Up I went, gradually leaving the protection of the trees for the spectacular views of the land around me. And the wind.

The clouds were mounting, although they did not look very threatening. What I didn't like was the wind. I was going to be above treeline quite a bit today, which could be unpleasant if the winds didn't die down. If they increased in strength, unpleasantness might be the best I could expect from the day. Still, the high, open land comforted me with its expansiveness. Big spaces, as the old salt or desert rat knows, are good for the soul. In the distance I could see large swaths of clear cuts, the logging companies having pushed right up to the boundaries of the park. The trail solidified on the ridge and, except for the punishing wind, the hiking was glorious. I felt myself pushing for LaCoulotte ridge, wanting to get to the hardest part of the day as soon as possible. The trail ran along the ridge, which bent into the shape of a canyon rim high above the lush land. And still the wind pummeled me.

The air was not warming up with the passing of the day and, with the exception of a highly odd canyon on the ridgeline, filled with snow, I was completely at the mercy of the wind. The skies were darkening, the clouds changing from puffy white to billowly slate. I thought about LaCoulotte and the cross country travel. My breaks became shorter and the trail started to thin out again as I rounded the hulk of Font Mountain.

I lost the trail up to the pass north of Font Mountain entirely, although this was not a great shame. There were no trees to block my progress, and I knew I had to go up to the pass. Once on top, however, I found only game trails. I walked down one, then another, then a third. Each was leading down the wrong side of the pass, rather than traversing along it. Finally, I followed the guidebook's directions exactly and found the trail precisely where Lynx said it would be. I hustled on, hoping that the weather would miraculously improve before I got on top of LaCoulotte ridge. I pondered the wisdom of going high and off trail with the wind and potential rain. There was an ATV track coming up that I could run down and then pick up a road to get back to Castle Mountain Ski Resort, through which the GDT passed. Around 1 in the afternoon, I found myself staring up at LaCoulotte ridge, the wind smashing me about. I scurried down the Scarpe creek a few hundred meters to pick up a liter of water for the upcoming traverse, which was waterless, and then hit in a thicket to escape from the wind. I snacked and tried to screw up my courage as best as I could. Having someone around to get strength from would have been nice. But, no one was around, and no one was coming for me. I had to do it myself.

I started up the hillside, alternating between rock gullies and vegetation. The grade was steep enough that I took to counting my steps. Forty steps, then rest. Forty steps, then rest. At a painfully slow rate, I hauled myself up to the top of the ridgeline and was stunned by the sight. The ridge had hidden most of the views, but once on top, I could not only see forever, but more importantly I could see the work ahead of me. A liter of water was not going to be enough. The wind ripped at me and my wind breaker no longer flapped: It hummed like a generator. Black clouds were on the horizon, and with the wind, they would be here soon.

Five minor mountains stood between myself and an old ATV track that the GDT took down to Castle Mountain. I paused and considered going back down. It would be easier, safer, and faster, I pondered. I was alone in a remote area with no prospect of other hikers finding me in case of trouble. I had never felt so alone, even in the midst of the desert. Pride drove me forward. I began the slog up the first peak, dodging the few trees that had managed to get a foot hold in this beautiful, awful land. A few boulders had to be scrambled over, but mostly the ascent was fairly gentle. The descent, on the other hand, was complete scree. Steep, sliding rock makes for unsure footing and a slow, deliberate pace. I tried not to think too hard about falling on my way down to the gap between the first and second peaks. I tried simply to walk and let my body take care of things. I looked off into the horizon to check the clouds and the mountains. Both were still there, shockingly enough.

Arriving, finally, at the pass, I did not dawdle. The wind was punishing and the air was cold. Any break in the full force of the wind would soon result in an uncomfortable body temperature. My exertions had left me drenched in sweat and now I was cold. Up the second peak I had to go. There was nothing at all to block the wind. The mountain was curiously devoid of even the smallest vegetation. I pushed up through the rock and scree, straining and sweating. The wind intensified. Even my pants, made from tough, heavy Schoeller Dryskin, began to hum, although at a more baritone level than my windbreaker. As I neared the top a small clump of trees appeared. Providence. In my haste to reach them, I mistepped, striking my knee hard on a boulder and bringing forth a howl of pain. I wallowed over underneath a tree, grimacing in pain, but happy to be mostly out of the wind. I had been hiking for 90 minutes and wasn't even to the top of the second of the five peaks. I began to consider my options. If I continued at this pace, it would likely be quite late when I got to the last of the five peaks. The weather looked like it was getting worse, not better. I would soon be running on caloric fumes, although I could dig into my food bag for some of tomorrow's snacks to make up for a late dinner. I now had a hurt knee. I could return to Scarpe creek. I had no one to impress and there is no shame in turning around. Pride drove up up LaCoulotte ridge, and pride drove me on again. Or, perhaps, stupidity.

Moving slowly, I re-entered the wind and picked my way up to the top of the second peak, taking care not to overly stress my knee. At the top, I wanted to cry. LaCoulotte peak stood in front of me. It was not going to be easy. I was scared.

Very cautiously did I pick my way down from the top of the second peak, weaving inbetween the few trees and shrubs that were growing near the gap between the mountains. LaCoulotte had stands of trees dotting on of it flanks, which would make for reasonable footing, but also for many obstacles to push through. The direct route, straight up the ridge coming down from the summit looked safe, but with very poor footing and no protection from the wind. As I dropped down, the peak got larger until, standing at the gap, I again thought about turning around. Once I got to the top of LaCoulotte there was no going back. I thought about what others might feel if I happened to take a tumble out here and end up dead. I tried to think my way out of my mental funk. Objectively, there were no real dangers, only hard work. If I was careful, there was nothing to worry about other than a freakish accident, and that could happen to me anywhere. My best efforts were as nothing compared to finding what seemed like a very faint climbers trail heading toward the stands of trees. I no longer felt so alone. The climbers trail turned out to be nothing more than some hikers foots steps in the scree. With every step I slid. I abandoned the foot steps and headed directly up hill into the trees, where the vegetation would provide better footing and something to grab on to.

Very slowly, I climbed up the side of LaCoulotte using the trees as much as I could to help me The stand I was in thinned, and I was left with neither holds nor reasonable footing. The scree was unbearable. For each step up the steep grade, I slid two thirds of the way back down. Sometimes my plant leg would slide a foot down hill. The wind crashed around me to the point where I could barely move without being knocked off balance by it. Despite the sky directly overhead being blue, a stinging hail began to pelt me. Blown from the clouds far in the distance by the cruel wind, the hail pricked and prodded me, adding another discomfort to the climb. I took to counting steps. Ten steps, rest. Five steps, rest. Five steps, rest. Step, rest. I began scanning the slope above me looking for any sign of vegetation that might indicate firmer ground. My progress was agonizing. Ten minutes, twenty minutes, thirty minutes. Still, I had not reached the top. Improbably, the scree began to get larger and the footing better as I neared the top. Large, black, lichen streaked boulders formed a final bit of scrambling. Even this took more time that usual, as the wind kept me from hopping about as I was used to doing. Struggling, I reached the last rock on top. There was nothing there except an upset grouse.

I was beat. Defeated. Crushed. I didn't even bother to look to see what I had accomplished. I looked, instead, for a rock to sit by and rest. Sweat poured off of me. Clouds of steam gushed off of my face and out of my windshirt. I leaned against a rock, partially out of the wind, and a meter or two from the grouse. And I sat. I took a drink of water before getting cold and worked on a Snickers bar. Ten minutes went by before I bothered to look at the vista in front of me. I could appreciate it once again. Things were not so bad, I reasoned. I was in a beautiful place and I had it all to myself. My knee was feeling better and I was half way done with the traverse. It had taken me nearly two hours to go from the top of the second peak to the top of LaCoulotte peak. I wanted to hope that the final two peaks would be easier than the first three. I had to get over them now. There was no turning around. I read over the guidebook another time and looked at my compass, trying to figure out which route I was to take off of LaCoulotte. An alternate headed in one direction, but the guidebook described it as challenging. I wanted easy right now. Back in the wind, accompanied by the hum of my clothes, I started dropping down LaCoulotte, taking care not to go too far down the slope, as Lynx warned of a band of rock that faced the hiker too eager to lose elevation. A few scrub trees provided some break from the wind. My hands began to chill and the skin become numb. It was cold, I was almost out of water, and I still had to get off LaCoulotte and over two more peaks before reaching the safety of an ATV track.

Although I tried to stay to the left, I ended up on top of the rock band that Lynx had warned of. Although not far down, the slope beneath it was steep, and I couldn't afford to risk simply jumping down. I retreated along the rock band looking for a way to climb down. Twenty or thirty meters away, I found what looked like a reasonable sequence of ledges and started downclimbing. Only a few feet from the bottom, I found that I could not go further without jumping or pushing my skill beyond what it could bear. The slope was just too steep. I started climbing up when one of the footholds simply broke and gave way. My body swung lightly as I shifted weight to the one good foothold and clung tightly to the rock. Calming myself, I relaxed the death grip I had on the rock and finished climbing back up the rock band. I moved another few meters along the top of the band to small gully, which conveniently had a small tree coming up through it. Carefully, and using the tree, I was able to get down the rock band and onto the slope below. I slowly negotiated the steep screen slope, broken up by clumps of vegetation, and reached the bottom of the rock band where I had initially been cliffed out.

Staring at me was the fourth peak, a steep and rough looking red mountain, but one which appeared to have a faint climbers trail on it. Overjoyed, I moved quickly, for once, down the rest of LaCoulotte and attacked the red mountain. The climbers trail was steep and direct, and barely there, but it gave me confidence. Once again, I was not alone on the ridge. Counting steps again, although this time back in the fifties, I surmounted the red mountain and was calm enough on top to savor the views of the massive land around me. The grandeur of Waterton and the mountains in northern Montana were spread out to the south, clear cuts to the north, where I was heading. The alternate route on Barnaby ridge could be seen clearly coming off of LaCoulotte peak. More importantly, for the moment, I could see my ATV track and the last of the five peaks. The smallest and easiest looking, it would be a breeze to get over. The ATV track cut down the side of the mountain, running north toward Castle Mountain Ski resort. I began my descent of the red mountain, thirsty and hungry but confident for the first time today. Glancing backward, I was pleased with what I had so far accomplished.

I still, however, had some work to do.

The dark clouds had arrived and rain seemed imminent. I needed a break, however, and found a few trees in which to hide from the wide and occasional hail. I had only a sip or two of water left and was extremely thirsty after the exertions of the afternoon. I saved a last sip for the a celebration at the ATV track. Although tired, I was cold enough that I had to start moving again or risk hypothermia. The fifth and final peak was as easy as I thought, both in terms of steepness and the total elevation gain. Once on top, I barely paused for the views, after all I had been on the ridgeline for more than five hours, and now I was racing the rain. I trampled over a few small snow banks, making sure to stay off any potential cornices, and dropped down a thin scree ridge to reach the ATV track. The rain came.

I gave a war whoop, donned my rain jacket, put on my pack cover, and drank down my celebratory water. I was still very thirsty, but at least I was back on a trail and could cruise down hill for a while. My stomach rumbled for food and my parched throat cried out for liquid, but I had several kilometers to cover before I would reach a stream. The rain came down softly and the wind died out. Even the rain stopped after a few minutes, by which time I was scampering along the ATV track directly above the valley that ran into Castle Mountain. Providence seemed to approve of my exertions, and painted a large rainbow across the valley.

The ATV track was obviously no longer used, as parts of it had broken off and tumbled down into the valley below. While easy for a person on foot to get around, they would not have been possible to traverse on a four wheeled machine. The trail steepened significantly as it entered the forest. Thick downfall blocked the way, and at times I could not see the track except for looking at my feet. Dead trees, overgrown shrubs, and other annoyances blocked my path, but these seemed to me to be rather poor obstacles after my experience on LaCoulotte ridge. A few kilometers down the old ATV track a gushing stream came down from the mountains, providing a much needed water source. Greedily, I set to cooking dinner and hydrating. Nothing could taste better than the wild mushroom couscous I plowed through, accompanied by pure mountain water. With the drop in elevation, the day was even warming up, especially as I no longer had wind to worry about. After 45 minutes of resting, I continued down the track, glad to be walking along such easy terrain.

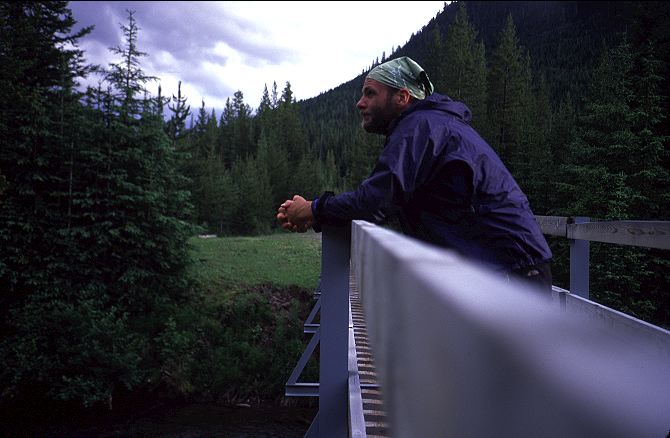

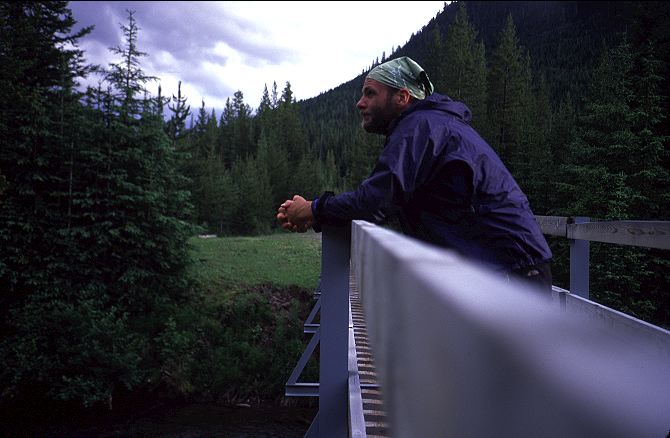

I had no particular place in mind to camp, but Castle Mountain Ski Resort kept popping into my head. They might have a place to eat breakfast tomorrow, or to have a beer tonight. The skies continued to blue and by the time I reached the valley floor, the trail had (mostly) cleared and the track became nice, flat walking along the banks of the Castle River. Two fords of tributaries of the Castle were uneventful. Even though I had been walking most of the day, and was tired, I kept plowing along, so thrilled was I at the easy track. With delightful weather and easy trail ahead, how could I not be happy? Big mountains rimmed the valley, with the Barnaby ridge alternate route towering above me to the left. It looked like a fun bit of work, but for another time and with other people. I had gotten along LaCoulotte ridge, but the margin was very slim. I paused over a bridged tributary where the camping looked good. I could stop here, in this pleasant spot. But Castle and a beer were pulling at me. On I walked into the darkening day.

it was 9:30 by the time I finally rolled into Castle Mountain Ski resort on the now truck-wide road. A real dump in the summer, it seemed. The bar was closed (it was Sunday), the bathrooms locked, and all the water turned off. I found a spot to camp next to some RVs and set up on rock hard ground. Compared to the innumerable quality camp sites on the walk in, I felt rather foolish for having pushed so hard to get here. I had covered 42 kilometers today. More than 25 miles over very tricky ground covered in nearly 14 hours. I was wiped out and hoped for an easier day tomorrow. Even though the scenery was grand, the price it had extracted was high. I needed some down time before I had to wage another such battle. It was with an Empty mind that I fell asleep on the hard, cold ground.

The ground was still hard and cold when I woke in the morning, the air was cold but the skies were glorious. The high winds of the day before had blown everything out of the area and the weather was stable. I lazed in camp drinking tea and reading the guidebook, munching on gooey oatmeal bars. The day looked easy and with lots of ATV tracks and dirt roads. I could make Coleman tomorrow without much difficulty and that thought comforted me. My aloneness had seemed to vanish with LaCoulotte ridge and I was again comfortable without anyone around. The GDT followed the road out of the ski resort. Only a few minutes out, a medium sized black bear loped across the road twenty meters in front of me. A reminder that I should not sleep with my food anymore. The alternate route on Barnaby ridge came down to meet the road and shortly there after I hit the bridge over Suicide creek. Two trails, one on each side, led up to Syncline mountain, the lumpy green and grey rock over head. I pondered the guidebook for a moment, which turned into a full thirty minute break by the pleasant creek under the increasing warm sun. My black pants and black shirt seemed appropriate yesterday in the cold air, but not now, under the hot sky.

I followed the ATV track up and into the woods, climbing hard for twenty minutes before reaching flatter ground at a perch with a view down into the valley holding the ski resort. I followed the easy ATV track as it wound throw the woods, enjoying the easy walking and weather. No cares, no worries, just here and now. The ATV track would occasionally degenerate into mud pools, necessitating an occasional bushwhack, but there were no route finding problems or large peaks to climb or scree to deal with. Pretty flowers, the occasional view out to a distant mountain, and a soft, warm wind were the worst conditions I had to overcome.

A couple of hours later, I found the pleasantness gone, replaced with clear cuts and long mud swimming pools. Numerous ATV tracks led off in innumerable directions and the sun was actually hot. Dusty air and the high pitched whines of two stroke motorcycles completed the experience. I declined to look at the map or guidebook and instead stayed on the largest track, which ever way it bent. Two motorcycles idled past, stopped, looked at maps, and then drove away. A few minutes later they were back, apparently as lost as I was. However, I was headed in a direction and didn't really care what particular route I took to get there. I ambled along until I hit a large gravel road. The signs that the guidebook indicated would be there were, in fact, missing. As I had not bothered to follow the guidebook, this didn't surprise me much. I left the swathes of naked land and followed the road, where the signs the book mentioned were placed, shrugged my shoulders, and pushed on. The clear cuts had given way to cattle ranching on Lynx Creek road. The cattle ranches had apparently burned last year. The land was tired, it seemed.

I took a long break at the Lynx Creek campground, a pleasant spot with closed bathrooms right on the banks of Lynx Creek. I sat in the shade and ate some noodles, napped briefly, then ate some nutella burritos for desert. I had not eaten much the day before and had some extra food to stuff myself with. Around 2:30 I set out down Lynx Creek road with my eyes on my watch. I had to make a turn off on an unmarked ATV track in 4.8 K and I didn't want to miss it. After thirty minutes, I did, in fact, pass an unmarked ATV track. But, declining to check the map, I powered on, assured that I had not gone 4.8 K. After another 30 minutes, I realized that I really did want to take the previous ATV track. But, walking alongside the banks of the creek and letting the world go by at 5 K an hour was just too indulgent to pass up. So, I continued along the road. Looking up, I could see the ridge that the GDT was traversing. It had burned hard the summer before and deadfall might be precarious up there. I was happy where I was.

Along the road were camped what appeared to be squatters. People with old RVs that had clearly been there quite some time (some had flower gardens). Not just one or two people, but a small colony of people living a kilometer or two apart, doing whatever seemed right to them at the time. This was Crown land, which seems to mean that people can do what they want as long as they don't cut down the forest or dig up minerals. For that, they have to file paper work and pay money. An elderly couple was cutting deadfall by the side of the road and I waved to them in a friendly way that reflected how nice the world seemed at the moment. They seemed surprised to see me walking down the road, but waved back nonetheless. Thirty minutes later, they came driving past in their pickup truck and pulled alongside for a chat. They offered me a ride into town, which I declined and told them my story. They were surprised, to put it mildly. They said people hiked in the hills with some frequency, some of them going as far as Waterton. But, they had never run into anyone trying to hike the GDT all the way to Mount Robson. We talked for fifteen minutes about the route up ahead. I had planned on going into Coleman to resupply and was going to pick up the GDT where it intersected the road a few kilometers up. From the intersection, the GDT takes an ATV track to another gravel road, which runs into Coleman. The couple very astutely pointed out (I had not grasped it) that I was on a gravel road already. Why work hard to get to yet another one, only to go into Coleman, which had minimal supplies? Their logic seemed to overpower any notion I had of going directly into Coleman. Lynx Creek road runs right into Blairemore, which has an actual supermarket. From there, you could just walk or hitch on HWY 3 to get into Coleman. Their suggestion seemed to make perfect sense, and I began to wonder why the GDT didn't go there in the first place. Then, it occurred to me, there is no GDT. There is no official route. Much of the GDT is simply what the guidebook says it is. Lynx picked out a good route from Waterton to Castle Mountain, but here it seemed more natural to go into Blairemore, so that was where I was heading. I'd have a few kilometers along a busy highway, but I didn't mind that too much. I thanked the couple. As they drove off, they mentioned that there was active logging ahead and warned me to find a good campsite for the night. I waved, they waved, and they were gone from my immediate life.

The day turned hot. The road had minimal shade as the area had burned the summer before. It had been clear cut before that. A few cars passed me on the road, heading in from Blairemore to cut wood or visit friends or fish or do whatever. Weaving my way down the road mountains rose up in the distance, reminding me that I needed to get back into the hills sometime soon. The big national park mountains were far in the distance, but in a few days I would hopefully be back in the alpine. For now, distant views would have to do.

The road began to push upwards and the sweat started flowing freely. A truck passed, then repassed me ten minutes later. I walked by the junction with the GDT, and the truck repassed me again. I waved for a third time, which both myself and the two occupants found strangely funny. Pushing higher and higher I finally gained some shade from trees growing alongside the road and made the final push up to the pass. I made the final push to the top. I made the final push to the edge of the logging operation. Sweat was pouring off of my hands and onto my camera, but I took pictures anyways.

All around me mountains stretched their bulk into the sky, their flanks stripped of anything that one might call a tree. The land wasn't tired. It was broken. A ghastly sight and one that instilled neither anger nor rage, but only shame and embarrassment. The fact that I wasn't Canadian and that this land was not part of my heritage seemed not to matter in the least. I was embarrassed for the human race. That we might destroy a land like this. Certainly hikers and climbers could not longer use it. But, hunters would no longer spend much time here. The Game would have fled long ago, quite literally for greener pastures.

Who would ever want to come here? Fishermen could find better streams elsewhere. Trail riders? Ditto. Even ATVers could find better places elsewhere. This land was done. I felt like lighting millions of forest fires and finishing the job that the lumber companies had started. There was nothing to be done now. In a thousand years or so, the land might come back. Then again, it might not. It is possible to so thoroughly destroy a forest system that it never returns to anything resembling a forest. Time would tell, but by then other areas might be torn down as well. Perhaps there were plans to strip mine the land after the lumber companies were done. I am not against the logging of forests. Much of lives is built around access to lumber. It has to come from somewhere, unless we are willing to make a lot of changes. But, it seems that it could be done in a more responsible, less destructive method. But not here, it seems.

I left the pass area and headed down hill, feeling crestfallen. Who had the solution? I certainly didn't, and it didn't seem very fair of me to criticize people who were trying to make a living if I didn't. Or, rather, had an alternate suggestion for how they might make a living. Only so many people could guide others into the area. There was only so much help needed in tourism. Without an alternative, it seemed akin to my knocking over someone's house (or country) and not helping them rebuild a better one. I took comfort in the idea that this might be isolated. I had seen plenty of clear cuts from up high on LaCoulotte and Lineham ridges, but they didn't seem as large and expansive as this one. It continued down the hillside. Whole city blocks of trees were gone, their soil to follow when it rained. The mountainsides cast that light that makes Death Valley seem so surreal. It is appealing in the desert. Here, it is not. I walked down past more and more cutting operations and saw more squatters. These, however, seemed different than those on the other side of the pass. Mixed in with people on ATVs, they were hunting for wild mushrooms. Several offered me rides down the hill to one of the mushroom buyers, but I didn't want to be around others at this particular moment.

Passing by one of the mushroom buyer stands, I slowed to see what it was the forest was producing. Morels seemed to be the prime target. Morels the size of bananas. Last year the forest had burned. This spring had seen much rain. Apparently, these are the ideal conditions for spring mushrooms. The buyers were paying phenomenal amounts for the morels and had crates upon crates of them stacked up alongside their roadside homes (RVs and trailers). I could tick off one more activity that would cease when the timber companies reached this tract of forest.

The sun was beginning to drop down and I was beginning to feel tired. Weary, perhaps, is a more adequate description. Glancing around, I decided to head up onto a hill above the road which had been stripped of most of its trees, figuring that I would incur the wrath of neither the logger nor the hunter in this case. Soft, pleasant ground greeted me in a field; my first soft bed since beginning the trek. I hung my food off of a sickly looking tree that had escaped the chainsaw and rolled under my tarp. Blairemore was only two kilometers away. I thought about the 47 K I had covered today and compared them with the 42 from yesterday. I thought what the clear cuts told us about humankind. I thought about how fun it might be to become a squatter out here for a summer or a year or a decade. A decade probably wouldn't be feasible, as the timber companies would no doubt want me off to cut down some more trees, to make a few more dollars.