Field to The Crossing

July 23, 2004

Morning on the Kicking Horse came with the rattle of diesel engines. It had been quiet most of the night, with only the occasional train to disturb my slumber. Unlike US Interstates, it seems the TransCanada shuts down over night. I hiked in toward Field along the sandy banks of the Kicking Horse, but had to scramble back up the highway for the last few hundred meters.

I crossed the Kicking Horse on a bridge and came into town, at least what there was of it. I wandered through the residential part of town and found that almost every little house had a B&B sign on it, with a No Vacancy sign hanging below that. There was a school, a PO, some tourist offices for Parks Canada, and a large commercial inn, also with a No Vacancy sign on it. Truffle Pigs Cafe sat across from the inn and had a reasonable looking menu, but was not due to open until 8. I sat next to some motorcycle riders, in full leathers, on a bench overlooking the railroad and river, and waited for the cafe to open. Tapping my feet gently, the hour finally came and the three of us rushed inside, making haste for the coffee pot.

I got a mug of coffee (Princess of Darkness) and a paper from the machine out front, and sat in peace, reading about the world and drinking the wonderful black brew. I had ordered huevos rancheros, but got something that looked suspiciously like a burrito. I ate it and confirmed that it was indeed a burrito, and its only resemblance to the famous egg dish was that both had eggs and tortilllas and beans. It was very tasty, however. I was still hungry and so ordered the French toast supreme, much to the amusement of the waitstaff. I explained how I had gotten into town and where I was going, which amused them even further. More coffee, and then the second breakfast. Again, the French toast had little resemblance to what I thought of as French toast: Bread (a nice brioche or challa) lightly battered in egg and then sauted to a a golden brown. This was more like hunks of a baguette with some sugar and baked. It was delicious, complete with blueberry cream cheese and syrup. Even after the two breakfasts I was still a little hungry, but declined to order a third breakfast. Canadians just don't have the breakfast stomachs of people in the States, it seems.

I retired to the bench overlooking the river to finish the paper and decide how to spend the rest of the day. Although there was a Parks Canada office in town, where I could have made reservations for Jasper, I decided not to, partly because it seemed silly given the number of backpackers I had seen thus far, but also because I didn't want to take up space from weekend hikers would might be denied a permit because I had made reservations that I had no intention of keeping. I eventually settled on walking over to one of the tourist centers to see what they had to offer. I ended up with eight postcards, which I promptly wrote out and mailed from the PO in town. No letter from Mom, which I thought a little odd. I tried to call her and Mark and Kristine, but my phone card (purchased in the US) didn't seem to work in Canada. So, back to Truffle Pigs, where I bought a phone card (they were also the only store in town) and then back to the phone to try calling around. Mom wasn't home, but I did manage to raise Kristine. I mostly just wanted them to bring me a fuel canister from Calgary, but it turned out they were going to be car camping in Peter Lougheed tonight and could come and grab me beforehand. I was rather amused with returning to the park.

I went back to Truffle Pigs for a Brie and ham sandwich for lunch and was treated to some free watermelon by one of the chefs in the cafe. I ate and then retired to the safety of the Kicking Horse, underneath the bridge. On my way there, the postmistress flagged me down and handed me a letter from Mom which had just arrived. I was able to reach her on the telephone and we chatted for about forty minutes, after which I made the bridge. Tourists had started to come out and I wanted to keep out of their way, particularly as I smelled rather atrocious and looked even worse. Dozing in the warm afternoon air, with some of my clothes and gear hanging in the scrub trees lining the bank, I decided that I rather liked Field, but would like it quite a bit more if there were fewer tourists. It would make for an interesting place to live, I thought, in its relative isolation during most of the year. After my nap I looked around under the bridge (nothing else to do) and found a recent set of bear tracks, a lot of deer sign, but no pirates gold or anything unusual. Satisfied that the Field bridge didn't hold any secrets that I needed to be aware of, I went back to Truffle Pigs and bought a half gallon of ice cream for an afternoon snack. Sitting under the local firetower and eating such a container of ice cream, with a spork, seemed to provide the passing tourists with a bit of entertainment. Although I looked homeless (and truly was), I was eating ice cream with a funny looking spoon, which meant that I had to have some money, and hence wasn't dangerous in their eyes. Mostly, they just seemed a little confused.

I polished off the ice cream and was still a bit hungry, but Mark and Kristine were due in town soon and so I declined to eat some more. I lounged across from Truffle Pigs on the porch of the community center, joined eventually by several employees of the cafe on their break. We talked for a while about the town and the area before they had to return to work and I had to get something else to eat. I went inside the cafe and got a cup of coffee and a sausage sandwich to go. When I came out, Mark and Kristine had just arrived. Although I had seen Kristine two weeks ago, I hadn't seen Mark for about three years. I had kept tabs on what he and Kristine had been up to through a mutual friend who worked with Mark on a variety of research topics. We drove back along the TransCanada, all the way to Canmore before stopping for dinner (I had only gotten down half of the sausage sandwich during the ride). We stopped at a pub for some beer and cheeseburgers (not up to PCT standards, but acceptable) and then hit a local beer and wine store before pushing on to Peter Lougheed. It took us some time to find the group campsite which a large collection of Mark and Kristine's friends had reserved a year in advance. Finally settled in after the long drive (long for Mark and Kristine), I thought about how odd it was that I was back here. It took me almost a week to walk from here to Field. It took us a few hours to drive it. I was something of the local freak, with my weather beaten face, salt stained clothes, and odd choice of summer vacations. But, fun all around. My tolerance for alcohol was extremely low after the summer's hiking and after a few pints of Strongbow Cider I had difficulty stumbling back to my tarp a little after midnight. Not philosophizing, just spinning.

I woke with a rather ferocious hang over, wanting nothing more than some coffee and a huge pile of greasy food. Mark and Kristine were up and about, so we packed our things, said our goodbyes to those of the party who were actually up, and set out for Field. Breakfast was on my mind, heavily, and so in Canmore we stopped to find a breakfast place, finally settling on a fancy looking cafe. I was sorry to have to go in smelling as I did, but there was nothing to be done. Besides, I rationalized, Canmore was an outdoor oriented town (as well as tourist oriented) and they were used to smelly people. More great coffee flowed, better even than the Princess of Darkness I had had in Field, and I pondered the menu, trying to think of what would give me the most calories. The pretty, young waitress eyed me with a mixture of curiosity and and hesitation. I finally settled on a benny (a variant of Eggs Benedict) for my first breakfast. While the food was being prepared the waitress came over to talk for a while, eventually getting my trip out of me (I didn't put up much resistance). She seemed interested. The food came and I scarfed it down, and order a fried egg breakfast sandwich for a second breakfast, which brought forth a little squeak of laughter from the waitress. I was rather sad when the time came to pay the bill and leave, wishing I had a few days in Canmore to look around and spend some time with the charming waitress, but Mark and Kristine and I had other things to do today.

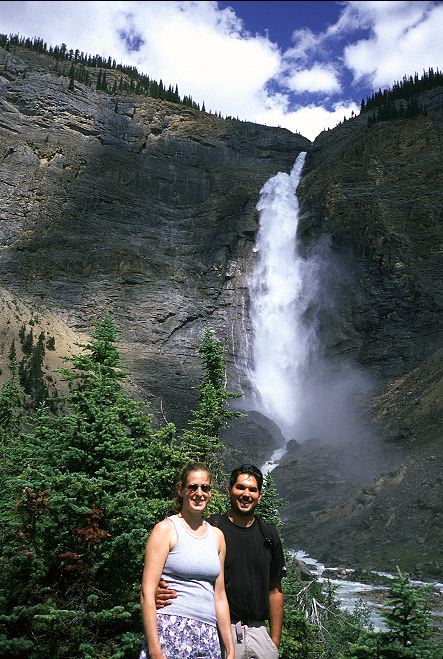

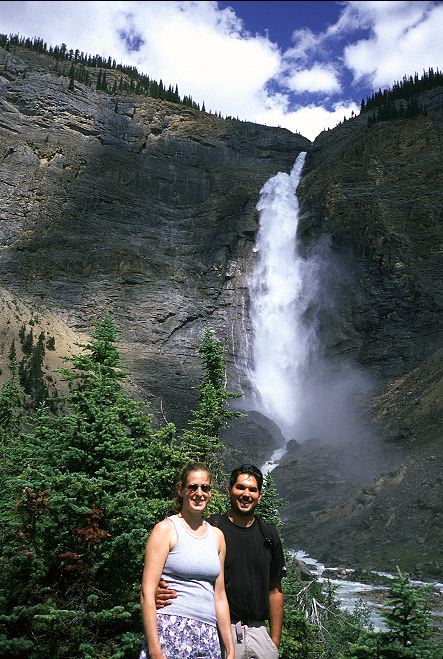

Next door to the cafe was a outdoor store and I was able to get another canister for my stove, thus freeing me from the tyranny of the fuel tabs. We headed toward Field with the idea of setting up camp in one of the local campgrounds and then day hiking a little in Yoho. We staked out a site in Monarch campground and decided to drive up to Emerald Lake via Natural Bridge, where I would pick up the GDT again. Natural Bridge was, surprisingly enough, a natural rock bridge that spanned the Kicking Horse river where it became bottled up. Many tourists were milling about, taking in sights. The road up to Emerald Lake was steep and twisty, but easily managed by the Bauer's Accord. The Walmart sized parking lot at Emerald Lake was filled to capacity, including long tour buses, which seemed somewhat improbable given the road to the lake. One look and the three of us decided it would be better to go elsewhere. Back down the road we went and over to Takakkaw Falls, which are the second highest in the Canadian Rockies. Although there were quite a number of people out, it was not nearly the scene as at the lake. I thought the falls were more impressive than those at Helmet, having a much larger flow and falling from a greater height. Indeed, the spray from the falls floated out quite a way from the base. A few idiots could be seen trying to scramble up the talus slopes of the base and I wondered how long it would be before the warden's had to rescue someone. Perhaps that was why I hadn't seen any warden's in the backcountry.

After looking over the falls, we decided to hike up to a small lake on the other side of the valley where there might be fewer people. We passed a hostel (parking lot filled with cars) and began the short climb up to Hidden Lake. It was just enough to make me sweat, but not enough to tire me during my day off. The trail ended near the lake and we had to follow a game trail around to the far side where there was a bit of a beach. It had taken us less than an hour to get here from the falls, but it was empty of other hikers. There were more important, and easier, places to draw the attention of those with limited time. We sat and ate brie and aged cheddar and bits of other food that Mark and Kristine had brought with them. Lounging, with nothing else to do but lounge, is a great pastime. We pondered whether or not to continue hiking uphill toward another lake and put in a full day hike, but it was getting time to start thinking about dinner and so we headed back down toward the car and the falls, taking the easy way out.

We returned to the campground where I sorted out the maps I would need to get me to Jasper and the box of food that I had bought in Calgary. I also had a new pair of shoes and so, with a little sadness, pitched the old pair into the trashcan. I had gotten them in Unionville, NY on the Appalachian Trail and they were now like an old friend to me. Progress, however, takes its toll. Back to Truffle Pigs for the nightly feast, where I was now known by sight (anyone that wasn't a tourist stood out in town). I had a splendid dinner, but did have to drop $40 on it. I had a few beers and an order of mussels, along with a salad and a Middle Eastern inspired vegetable ragout with chicken. Quality food costs, and the chef at Truffle Pigs knew his business. We retired to the campground, where I cooled down some beer in the Kicking Horse, and sat up talking for few hours. There was so much to catch up on, but all of us were still feeling effects from the previous night in Peter Lougheed. Plus, I had to hike tomorrow along a path that the guidebook described in not-so-glowing terms. It was time for sleep as surely as tomorrow would be the time to push further north. I retired to my tarp and finished The Four Noble Truths, which I had concluded was too basic, too simple, to answer any of the questions that I had about Buddhism. I had a new book on Buddhism to work through, and hoped that it might reveal answers to the questions that I had been struggling with this summer.

Mark, Kristine, and I packed up from Monarch camp in the early morning and drove into Field for a little last coffee and pastries before I hit the GDT again. I downed a few cups of Princess of Darkness at Truffle Pigs and bought four very large day old pastries for breakfast. A few final goodbyes to the staff at Truffle Pigs and I was off. The natural bridge trailhead was deserted at this early hour of 9 am. No tourists, no cars, no buses. We said our goodbyes and the Bauers headed back to Calgary, leaving me alone in the parking lot. I sat and watched the falls for a few minutes and finished off the last of the Princess of Darkness. Some park workers rolled up in a truck to empty the garbage cans in the parking lot and restock the outhouse.

The GDT took the Amiskwi Pass trail, an old fire road, through Yoho National Park and, despite two mountain bikers early on, the solitude was stunning and the hiking easy. The guidebook had warned that the area had burned a few years ago and was now dry, dusty, and sun baked. While it technically was heading for a pass, the grade of the old fire road was gentle enough not to be noticeable. Wild flowers dotted the land (a great side benefit of forest fires) and occasionally large mountains would come into the view as I worked my way up the valley toward the pass. Despite the beauty around me and the wild feeling of the land (even with the old road), I was just not into hiking.

Sitting in the shade of a fragrant pine, I was able to put my finger on what was bothering me: Mark and Kristine were now back in Calgary, showered, clean, and sitting on soft sofas drinking rum and cokes, or maybe a Scotch. I was sitting under a tree, and for the moment it seemed like a poor trade. I pushed some dirt around with a stick and then threw it in to the woods. I just didn't feeling like hiking right now. I felt like the comforts of civilization. I hadn't even gotten a shower during my two days off in Field, nor had I washed clothes, or watched television, or slept or sat on anything soft. My days in Field were much like my days on the trail, except with better access to food and a lack of walking. To make things worse, it was going to be a rather long while before I reached another town. A few hundred kilometers, in fact, to the north lay Jasper. Even there, however, I might find row after row of overpriced motels, filled to capacity. But, surely there would at least be a laundromat in town. I could bathe along the way, find some river, but wanted, and needed, my clothes to be clean for at least a few minutes. I tried to stop feeling sorry for myself, but the image of Mark and Kristine lounging was strong. I had to walk.

I walked and walked and walked, and occasionally hiked. There was nothing to do but to go forward and let myself melt into the land around me. This, indeed, proved easy to do and after a few hours I forgot all about the plush loveseat in Mark and Kristine's front room back in Calgary. The valley began to open up and the fireroad degraded itself into an honest trail, unmaintained it seemed. I would lose the trail occasionally, but always pick it up again. Pack trains and small group equestrians seemed to keep the trail alive by their hooves. Certainly hikers were not doing much here, and this suited me just fine. Not only was the land empty of people, but there didn't even seem to be a chance of running into others. With so much splendor nearby, this area would be overlooked by people with a week of vacation time to spend in the outofdoors mall that is the Canadian Rockies. My mood had reversed, and I loved being where I was.

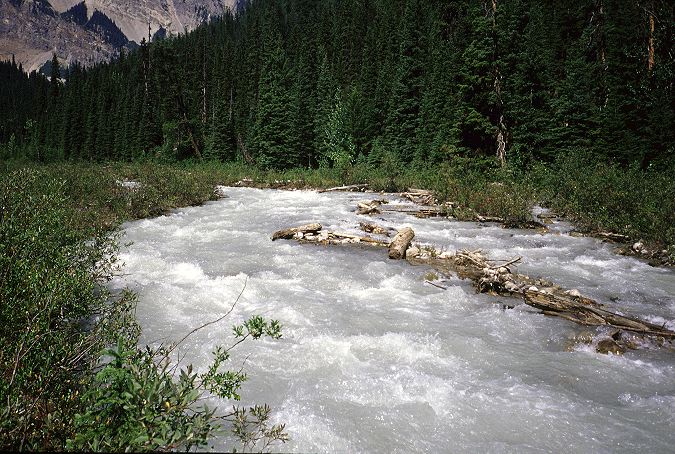

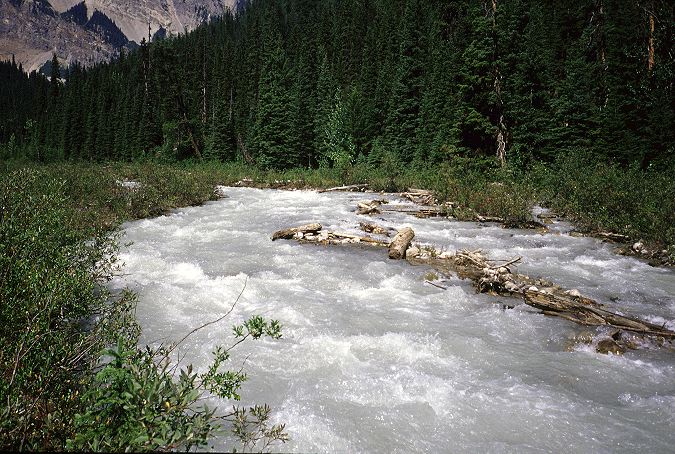

I stopped before my first river ford to relax a bit before getting my feet wet and pondered going for a swim. But, the creek was fast enough that I might have to do some work to keep from flowing down the river back toward Field. Large water falls could be seen in the distance, up the valley, and my map indicated that they were near Amiskwi Pass, where I thought I might make camp for the night. I forded the creek, which was mid thigh on me, but clear of obstructions, and quickly lost the trail on the other side. Apparently it bent in some direction other than up valley and when I could not find it, I simply headed across the mostly open land, following the river up. Ten minutes later, I recovered the trail or, rather, the horse track, although I would lose it again shortly. Another ford of the same river (why didn't I just stay on the other bank?) brought me back to a trail-less section. Before hunting for the trail, I sat by the creek to rest for a while and eat dinner (fancy kimchi ramen) and contemplate the upper end of the valley. I was only a few hours from the pass and had plenty of daylight left. Sitting in the shade of a gnarly scrub tree, everything was right again. My dinner was cooking, I was feeling strong and fit, and there was nowhere else I wanted to be. Pretty flowers provided some color, distant mountains provided my entertainment. I had plenty of good, clean water, and there was little danger of being overrun with tourists here. Indeed, I probably could have sat under the tree for a week and seen no one. Buddha had obtained enlightenment while sitting under the bodi tree. Perhaps I would think of something original while sitting under this trash tree, so ugly and bent and withered, yet so alluring, sheltering, and comforting. Just me, my tree, and my ramen. I apologized to the river for forgetting it during my musings and tucked into dinner.

I had one more actual ford of the Amiskwi river, getting wet up to my calves, before the trail began to actually climb, lifting me into the last of the burned out areas. The land was recovering quite well, I thought, with the burned trees mostly fallen and covered by new growth. Nature was working, unfettered by our helping hands, and working well. I passed by the waterfall that I had seen in the distance and stepped over the trickle of the Amiskwi near its headwaters and picked up water for the night and morning before heading to the pass itself. With this last lift I entered into a different world, one that had not burned, a place more distant from the valley proper that was only a few kilometers away. Thick trees and long swathes of green grass replaced the scrub and flowers of the valley. When the trail, what there was of it, stopped climbing I decided that I was on the pass itself. It was hard to tell, as the Canadian passes were long and broad. I entered a boggy meadow and at the far end spied a marker, complete with antlers. The marker, as I found, was the boundary of Yoho National Park. On the other side I would enter the Golden Forest District, which was not appealing, given that Forest Districts seem to exist in Canada for the sole reason of marking off land to be clear cut. The meadow would do for the night and I rapidly set up my tarp, for the mosquitoes had come out of the afternoon slumber and were attacking in waves. Finding a place to throw a bear line was more difficult, as all the trees were of the evergreen variety, with no long, extended branches. After twenty minutes of searching, I was finally able to get my food high enough off the ground and far enough out from the trunk of a tree and retired to my the safety of my tarp. I had to kill fifty mosquitoes and other bugs that came in with me, but after that I was free from the pests.

Looking over my maps and guidebook, it seemed that I had some difficult trail ahead of me. There was a glacial creek ford coming up, and I would get to it mid-day tomorrow, just at the worst time. Beyond it lay the David Thompson Heritage trail, which Lynx described as an explorers route that perhaps is maintained only by the resident elk population. On the other side of Howse pass, the end of the DTHT, was Banff National Park and the Howse river, which I might be able to ford and cut off a few miles of forest and road walking. Beyond the Howse was my next resupply point at The Crossing. From there, I had options. The GDT took what sounded like a difficult route, almost all off trail, through the White Goat Wilderness and into the southern end of Jasper. There seemed to be several difficult fords, which worried me. The other option was to road walk up HWY 93 and go over Nigel Pass into Jasper and pick up the GDT at Boulder Creek, effectively cutting off a day. Or, I could continue up to the Columbia Icefields and be a tourist for a day. SnoCat tours of the icefield could be had for only $30 and the thought of riding out onto part of the largest icefield in North America in comfort and safety had some appeal. To do so, however, meant around 65 K of road walking and having to spend time with the people that I liked to poke fun at from time to time. I had plenty of time to consider my options and so put away the maps in favor of some Buddhism, courtesy of one E. Conze. The text that I was reading was a collection of some of the central writings of the Buddhist tradition, covering the different sects and branches, while trying to emphasize the unity and commonality of them all. The legend of the Buddha and the future was the first selection from the text. I found this as helpful and informative as the legend of Christ, or any other creation myth. It did, however, help to set context. I wasn't looking for religion and so the magical notions of how the Buddha attained enlightenment and later died did not inspire or help answer questions. I finished the selection and closed my eyes on the still-light day, hoping for good weather and a reasonable trail tomorrow.

Rain had fallen on several occasions last night, but it was no more than a few drops, it seemed, and by the time I awoke, around 6 am, the sky was dominant blue. Cold air temperatures meant that I had to scramble quickly to get my food out of the tree so that I could feed and drink tea. With the rotten fuel tabs discarded, and a full canister of isobutane, I relished the tea. Not only did it warm me up inside, but the caffeine perked me up and boosted my confidence in the day. By 7:30 I had broken camp and was leaving Yoho with a streaming cloud of mosquitoes behind me. The trail ran for a few meters, downslope, and then faded out near a creek, which my map told was named Ensign. Cutting cross country, I quickly picked up a large gravel road, above which I could spot a few cars in a rudimentary parking lot. There was a private lodge somewhere in the area, but I could not see it. The road was rough, and would give my car trouble, but was passable for those with high clearance. Despite seeing the cars, the land felt free and unconstrained by people. Mountains with big glaciers on them loomed on both sides of me, with the ones to the west the more powerful. I doubted they were in any park or protected area. Just stunning mountains on Crown land, ready to be mined.

The road wound around and around, dropping steeply at times and I lost the views of the mountains to the east, but retained those to the west. A tent was thrown up on the shoulder of the road and two packs and a stove were sitting outside of it. The tent occupants were not to be seen and presumably were still asleep. I hadn't seen anyone since the mountain bikers early yesterday morning, hadn't spoken a word to another human (although I had said plenty to the plants and creeks and rocks in the valley of the Amiskwi) since Mark and Kristine left me. I strolled down the road pondering the question of an eternal soul. If the basic tenet of Buddhism is correct, that all things are impermanent and without independent existence, then there could be no such thing as a soul, spirit, or other metaphysical construction that went beyond the land of sensory experience and, most importantly, was unique to each being. The mathematician in me focused on the consequences of this idea and disliked what I saw. For one thing, if people are punished in future lives for their actions in the past, then it seemed that something must be retained from life to life, something that the physical world could not touch, and this seemed to be at least a partial definition of a self or a soul. The Buddhist notion of Karma seemed to contradict their idea that there was no Self. A self contradictory philosophy was generally not worth pursuing. I looked up to see what the world had been doing during my thinking, and saw that it had not changed. I smiled at the mountains like I would a pretty girl.

I returned to my contemplations with a different angle: If there is no Self (or Soul or Spirit or whatever you want to call it), then was there any meaning to existence? It seemed that the answer had to be a resounding NO. Without an independent, unique soul, there could be no notion of heaven or an afterlife in paradise. There could be no moral or immoral actions as there was nothing to be marked or degraded by them (forgetting about Karma for the moment). Given this, was Buddhism nothing more than Eastern nihilism? I did not think so, as such a religion, or philosophy, would not have endured for thousands of years. I hoped that further reading in Conze might help and let the matters drift out of my mind. I washed socks instead.

I reached the bottom of the road about a half hour earlier than expected and met the bridge over the wide, fast, and very glacial Blaeberry river. I shuddered to think that I might find something similar when I reached Cairnes Creek and the start of the David Thompson Heritage Trail. There was no fording such a thing, only a desperate swim. Not being a desperate person, I would either have to retrace my steps, or climb high up the valley to ford Cairnes Creek near its source, which hopefully would be more manageable. I knew that neither option was realisitc (a glacial river isn't any weaker near its head and I wasn't turning around) but there was little I could do until I reached the creek itself. On the other side of the bridge I met the Blaeberry River road, which was very similar to the one I had just come down, only mostly flat: It was pleasant walking, even if I had the itch of worry about the future in my head.

The road was shorter than expected, and I mistakenly walked past the turnoff for the Cairnes creek ford and the DTHT and found myself next to a truck, completely with fencing around it, in the Cairnes Creek Campground. I couldn't hear the Cairnes due to the Blaeberry, on whose banks I stood. A register was tacked up on a tree and I opened it, looking for evidence of other hikers. Inside, I found a note left by two hikers who, it seemed, were on the GDT this summer. The engineers, way back at Shadow Lake, had been right! Only a couple days ahead of me! Unfortunately, there note also said that at 3:30, when they tried to cross, Cairnes Creek was impossible and they were staying the night. This did not bode well for me. There was no note saying that they had to turn around and I hoped that this meant they had gotten across in the morning when the flow would be less. A week before them was another note left by some hikers of the DTHT that were out scouting the ford before heading south from The Crossing. No follow up note to indicate that they made it. An odd note was left by someone who was hiking, improbably enough, from The Sea of Cortez to The Crossing! The next entries were months, and years, old. People, it seemed, just didn't come out here much. I wanted to take a break, but I also wanted to see what the Cairnes was like.

I left a note in the register, not only for the record but also for a friend of Birdie's (of PCT fame) that was supposed to be hiking the GDT this summer, only starting a week or ten days behind me.

I retraced my steps and took the turnoff to the DTHT, arriving shortly at Cairnes Creek. I was not happy with what I saw.

Cairnes Creek was not going to be a walkover and any thoughts of resting before the ford were banished from my head. I needed to be careful and do some snooping before entering into the silty waters. Checked upstream for any log bridges and found none. The Blaeberry was perhaps twenty meters downstream, which meant that if I fell, there was a good chance that I would be swept into it rather quickly. Assuming that I could ditch my pack rapidly, should be able to swim out of the Blaeberry before I was in trouble. Hopefully, I would be able to recover my pack, but this was doubtful. Even then, my gear would be soaked and the overnight temperatures meant that I would have to get a fire started in order to survice. Or, I'd have to hike all night to keep warm. There were enough downed trees in near the mouth to make drowning a distinct possibility: Getting swept under could happen, and that would be very bad. The Cairnes was fast and I could not see the bottom of it, only the numerous patches of whitewater that indicated the presence of submerged rocks. The rocks would make footing difficult and increase the chances of a fall, which I wanted to avoid at all costs.

I chucked a few heavy rocks into the creek to try to determine the depth. My estimate was that I would be in up to my waist by the middle of the creek. Matters were not helped by the fact that rocks the size of a grapefruit were swept away by the flow before they sank out of site. I moved up and down looking for a ford and debated whether to try a narrow, but fast and deep, section, or a slightly broader one. The narrow section meant that I would be in the water for less distance, but that the time would be harder. I might be able to get to the middle and then leap or swim to the other side. I decided against this and looked at the broader area. There was a rock bar that I could reach without trouble, leaving me with only six or seven meters of a ford. I found a log that I could use as a brace and might be heavy enough to be effective in the rapid water. Taller than me and about the diameter of my calves, it should work. I undid the sternum strap and hip belt on my pack to make ditching it, in the event of a fall, easier. A deep breath, and into the water I went.

A few steps into my knees got me to the rockbar. I stared at the other side and began my traditional tough-ford chant. "You're a machine. You're a beast. A beast. You can't be stopped." I stepped into the water again and braced myself with the log. I was quickly into my knees and moving my legs became difficult: When I picked up my foot, it was quickly swept away, making balance difficult. I planted the log, downstream, then wiggled a leg forward, searching by feel for rocks. The pressure on my legs became intense as I neared, slowly, the center. "A beast, a beast..." Eyes focused on the bank, it drew closer as I went in to my waist. A rock here, a rock there, and I was beginning to lose my balance. Planting the log became difficult as the fast current swept it away from the bottom before I get it planted. "A beast, a beast..." Water raged about me as I slowly moved away from the center, struggling to keep control over my body and over the fear in my mind. I was getting closer, but I was also starting to get out of control. A rock nearly felled me. The smallest of mistakes would put me in danger and I started to lose my mental balance. My physical balance began to waver a few meters from the bank. I was going in.

My log fell out of my hands as I began to topple over. My feet started to sweep away from me and I flailed, trying to get one last push. Fortunately, my downstream leg did not hit a rock, and I found enough solid ground for a leap out of the water. Powered by fear, I threw my body out of the water and managed to land with my chest and arms on the bank, clutching at bushes for security. My legs were pulled downstream, but I was safe. I hauled myself out of the water and stood on solid ground. I shouted an oath up stream toward the glacier whose melting ice I had fought against. Joyful at being on the other side, I hopped about in some sort of motion that I thought of as a victory dance, but would have been seen by a disinterested observer as mere flopping. It was time to rest and I found a bit of shade near the trail, where I could rest, eat, and dry my clothes and gear in a nearby patch of sunshine. I took my gear out of my pack and was glad to find that it was almost all dry, though the bottom of the pack itself was wet. I spread out my tarp and sleeping bag to dry from the condensation of the night before, and set my shoes out for good measure. My pants hanging on a nearby bush, I sat down to a well earned lunch of Nutella burritos and cashews and looked at the Cairnes. It was only 1:30.

I sat and looked and sat and looked, relieved at having gotten across the creek. Had the other GDT hikers been turned back? Were their bodies submerged under one of the downed trees? I had little desire to ford more such creeks and the GDT route to the north of The Crossing held less and less appeal. I had gotten out of Cairnes creek with a desperate leap. I might not be so lucky, particularly as one of the future fords was of something called Cataract Creek. After sitting for an hour, I packed up and started down the trail, which was supposed to take me to Howse Pass, only a few hours ahead, if the DTHT was in reasonable shape. If it wasn't, I might have another bushwhacking experience on the order of my ordeal moving up the Palliser.

Although the trail had some overgrowth, and was occasionally completely eroded, it was highly passable. Generally following the Blaeberry upstream, it sometimes cut into the woods to escape from the floods, and at other times got too close and was washed out, forcing me into the river for short stretches. Scenic, and in much better condition than I expected, the DTHT was fun to hike and I moved up the valley rather pleased with myself and with the land. For once, Forestry lands were not simply clear cut. Indeed, with a bridge across the Cairnes and a little work with a machete and a chainsaw, the DTHT could really be something. Thompson is one of the seminal figures in the history of the exploration of the Canadian West. A trader employed by the Northwest Company, Thompson spent a lifetime wandering through the mountains, looking for new trade routes to the Pacific and mapping lands that are still relatively unknown today. This route reflected a historical route that he had taken when he pioneered a trade route (used for centuries by the local inhabitants before him) over the relatively low Howse Pass (named for a later discoverer).

Two hours of hiking along the DTHT brought me to another glacial creek crossing, that of the outflow of the Lambe glacier. However, this one, as the guidebook told me, was bridged and indeed it was, in fact. A sturdy aluminum bridged spanned the raging outful, just below a picturesque set of falls, made even better by the light behind them. It seemed odd to me that there was a bridge here, and not one over the Cairnes. After all, getting a bridge in here required a lot of work. One could simply drive the materials to the Cairnes. I was, however, most grateful that the bridge was here and stopped to rest and cook a dinner of noodles with a packet sauce advertised as Tikki Masala flavor.

After lazing about for more than an hour, I set off to complete the DTHT and hopefully find good camping at Howse Pass. On the other side of the bridge was a small campsite, with two trails leading off from it. One followed the Blaeberry and looked bad. The other set off up hill in a perpendicular direction from the river and looked good. My map indicated that the DTHT ran along the Blaeberry, but my heart indicated that the one running away from it was better. Using the maxim of never leaving good trail for bad, I hiked up and away from the Blaeberry. Climbing uphill, the trail was a joy to hike. Most of the overgrowth of the lower part of the DTHT was cleared and the trail was mostly uneroded, though in spots the trail had sunk a meter below its walls. I moved up and around, winding on this excellent tread, until it spit me out into an meadow with a large mosquito pond in the middle. The trail ended at the edge of the meadow and I had to go in search of the trail. Nothing. I walked around the entire boundary without finding a trace. The mosquitoes had noticed me by now and were swarming. I swatted them as soon as they landed, but I could never get them all before I was bite. I would pop one and see my own blood run down my arm. I smashed one on the crown of my skull, and returned with a hand smeared red. I had to get out of the meadow and made another circular search, this time finding a trail that ran back in the direction I came. Not wanting to think, I hurried down it, but thick overgrowth slowed by progress enough for the bugs to keep up. I crashed through the growth for ten minutes before giving up on the long-since-gone trail. It was going in the wrong direction anyways, and my suspicion was that it was, in fact, the DTHT branch that connected with my branch down at the campsite on the Lambe outflow. I turned back into the trail of mosquitoes that I had brought with me and returned to the meadow for another search.

I successfully found the trail near where I had diverted onto the bad one, hidden behind some downed trees. The trail was good for only a short distance before it became so thickly overgrown that I could no longer see it, but could feel it with my feet. Long stretches were so densely over grown that, although my shoulder and head were above the level of the brush, no more of my body could be seen, even by myself. Mosquitoes swarmed and plagued me, but finally I cleared the last of the brush, covered with my own blood from dead mosquitoes, and was able to resume a pace fast enough for the bugs to leave me alone. Longing for the pass, and the respite that my tarp would give me, I powered my way through the forest and practically ran into the sign marking Howse Pass.

I could not rest, however, as I needed water for this evening and following morning and thus had to walk a few hundred meters, slightly downhill to a creek that I would have to ford in the morning. Water stocks replenished, I quickly returned to the pass and started looking for campsite. The pass was in the middle of a forest and the few clear areas were slopey and rooty. The pass itself was marked with a large historical sign and the traditional monument that discriminated between the boundaries of Alberta and British Columbia. This would be my last crossing of the Continental Divide until I reached Robson Pass, far in the north and almost at the end of my journey. Right next to the signs was an area just large enough for my tarp and, assured that no one else was coming this way tonight, set up camp almost on top of the trail. I smothered my face and head in DEET and put on my windshirt for protection. It was still early in the day, but I had no desire to leave this place until tomorrow morning.

The monument had been carved into by various hikers over the years and I spent sometime reading over the various inscriptions. Carving up a metal post in the middle of the woods seemed like a reasonable thing to do and I hunted around for a sharp rock with which to add my own scrawl. There were two inscriptions from GDT hikers. One dated to 1996, before Lynx had written his book, and was signed by one James Rhodes. The other was from 2003 and was left by two hikers I had heard of, but never met: Lindy and Marmot. I carved out my name and date on the back of the post that discussed the history of the pass area, and then turned around to read it. While Thompson was the first Whitey to get over the pass (in 1807), the pass itself was named for Joseph Howse, who led the first team from the Hudson's Bay Company over in 1809. With my food hung, I sat about, mostly ignored by the bugs, and read some Buddhism. I wanted answers to my contemplations in the morning, but few were forthcoming, as the selections still dealt with creation myths and the Buddhist notion of time (which bore no resemblance to any common place notion of time). I moved through the material, but none of it was what I wanted. I retired to my tarp, where I set a new record for dead bugs: By the time I was through, the killing walls of my tarp were littered with 56 corpses. Looking ahead on my maps, it seemed less and less likely that I would attempt the White Goat, with its bad trail and creek fords. With other around, it might be a fun trip. By myself, it seemed more and more foolish. That left some amount of road walking on HWY 93, possibly with a trip to the Columbia Icefields. I was going to make the Crossing tomorrow with some ease, although the bad descriptions of the trail in Banff might force some work out of me. I put the maps and guidebook away in disgust at myself for worrying about something over which I had no control. Falling asleep on the gentle pass, I reflected on the fact that I had not seen an actual human being since leaving Natural Bridge (the two mountain bikers). I had covered more than 80 K without a conversation or sighting. As close as it got was the tent near Amiskwi Pass and the truck at Cairnes Creek. Except for the ford today, this was turning into one of my favorite sections yet. Not because of the scenery, but because of the Land.

At home, in the normal routine of wake-eat-work-eat-sleep, there are few mornings like today, mornings when you wake up and are glad to be where you are, glad that a new day has come once again. Perhaps that is why long distance hiking is so addictive: Days are actually looked forward to, anticipated, and arrive with joy. It had condensed hard last night on the pass and it was colder than usual in the morning, but tea and gooey oatmeal bars helped get my body moving down the pass and into Banff National Park. Although the trail began nicely, rolling down the hillside and fording a few minor creeks, it quickly became littered with deadfall and overgrowth. The trailbed itself was in good shape and dry, but no one had bothered to come here with a chain saw for some time. I began having to scramble over trees or cut my way off trail to work around particularly bad falls. With the slow warming of the morning, mosquitoes began to come out en masse, excited at such a slow moving food source. The blowdowns became serious and my pace dropped to perhaps a kilometer per hour. The trail became lost in bogs and marshes, re-appearing every twenty meters or so, usually underneath a tree. My feet were soaked from the earlier fords, and now completely muddied by the marhses. Parks Canada had not bothered to build or maintain water bars along the trail (requires actual work), nor had they bothered to walk out with a chainsaw (easy work). What did the fees, that user pay to access the backcountry, pay for? Why charge for areas that clearly receive no attention from the Park Service work crews? In some areas the trail would return and evidence could be seen of chainsaw work from a few years ago. But, mostly I walking on the bodies of trees that had fallen on top of, and parallel to, the trail. Or, walking up to my ankles in mud. For almost four hours I struggled through the forest to reach the flood plain of the Howse., a distance of perhaps twelve kilometers.

When I finally saw my chance to dodge over to the flood plain, I took it, The plain was broad, open, braided. The Howse, like the Blaeberry and Cairnes Creek, was glacial fed, but was spread out into enough channels that it did not appear particularly threatening. I was hoping to ford it and reach a trail short cut on the other side. For now, however, the most important feature was the lack of trees on the plain itself. The trail cut back into the forest, and I refused to follow it. I would rather ford the channels constantly than deal with the forest again. Never leave good trail for bad. I set off down the flood plain under increasingly gray skies, which did little to dampen my happiness at being out of the forest. Mountains, as usual, rimmed the valley, with a few gaps here and there for valleys, snaking there way up to higher, further set-back peaks.

I was forced, at times, to walk a winding route along the flood plain in an attempt to minimize the number of channels that I would have to ford. The Howse was a tricky river. Though glacial fed, there were channels that ran a clear yellow, while others, close by, ran the pale blue-white that is so indicative of the alpine highlands of Canada. The lack of trees, and the shape of the flood plain, provided no defense against the wind and I felt my temperature dropping as the wind cooled down my soaking lower body. Into and out of a channel. Cross a rocky island. Repeat. I tired of the process and returned to the edge of the forest, where I spotted the trail in an open stretch of land. It seemed that the going was easier down here on the plain as opposed to the horrific conditions higher on the slopes. According to the guide, there was supposed to be a sign, on the trail, pointing me out and into the flood plain. If I forded the Howse, I could cut off a few kilometers of walking, including three or four on a road. All I had to do was get across the multi-channeled Howse. This didn't seem to be much of a problem, as the guidebook indicated that the main channel of the Howse was right next to the trail. So, if I could ford that, I should be okay. Moreover, I had been dipping into and out of various channels of the Howse and knew that it wasn't much of a problem. I found the sign and gladly turned off the trail and onto the flood plain.

I crossed a few braids to get to the first, big channel, which I took for the main. Although I went into the middle of my thighs, the flow was not hard and the bottom of the river clear of obstructions. No problem. I still had, perhaps, a hundred meters of flood plain to cross, and it wasn't clear where on the other side I was suppose to go, but I had the worst part behind me already. One ford, a second. A difficult one that I had to end run. Another difficult one that cause me yet another detour. Standing twenty meters from the other bank, I realized that the water had shifted since Lynx had last come through. The main channel was not on the east side of the flood plain, but on the west. The main channel was wide and looked deep. It wasn't particularly fast, but it was wide and I could not see the bottom. It would not have to be much deeper than the other channels in order to sweep me away. If I didn't have my pack I could have swum across without much difficulty. Standing in the wind, a bit cold, I was most decidedly not happy.

I pushed out into the main channel and was in up to my waist after less than 5 meters. I turned around and looked for shallower or narrower crossing point. I picked up a gnarled piece of drift would to use for support and to test the deepness of the river. And thus began my two hour assault on the river, for the purpose of saving a few kilometers of walking. The actual benefits of taking the short cut had disappeared on the flood plain. Now, I was battling only for pride. I moved down the plain and attempted a re-ford. Same result. I moved further down and eyed the banks for anything that might indicate a ford that would be below my waist. At one point I was within seven meters of the other bank before I had to turn back or risk falling in. At one point I walked off an underwater cliff in a shallow channel and fell face first into the water, soaking my entire body, though my pack stayed dry. The cold wind and the steel sky brought thoughts of Solzhenitsyn into my head, images of hunting scenes from Tolstoy. I had made four assaults upon the Howse and all four had been repelled by the main channel. While it is possible that there is a viable ford for humans, I could not find it. Beaten and cold, I recrossed the minor channels of the Howse and climbed up a small ridge to find the trail. Huddled next to a tree for wind protection, I rested my cold and wet body, at least while I still had body warmth from exertion. My breaks, from now on, would have to be short, lasting only as long as residual warmth lasted.

I estimated that I had, perhaps 10 K left to HWY 93, which I would then road walk to the Crossing, a few K further up the road. From there, the Blaeberry, Cairnes, and Howse all told me, rather directly, not to follow the GDT into the White Goat and southern Jasper. The risks of the creek fords on that route were just too high for me to stomach. Instead, I was taking to the shoulder of HWY 93 for perhaps 40 K to a trailhead leading up and over Nigel Pass, where the GDT comes into the main part of Jasper. It would be safe and hopefully pretty as well. The highways in the Rockys were scenic to begin with, except for the clogs of cars, and the Canadians seemed to build them with walkers in mind. There was a campground, and a hostel, at Rampart Creek, about 10 K north from the Crossing on HWY 93. While it might be nice to get to there, HWY 93 ran parallel to the North Saskatchewan River and on my map it appeared to have flood plain even larger than the Howse (the two meet near The Crossing), which would make for an attractive, if illegal, campsite.

I began to hike rapidly down the trail, taking a pace that was useful only for getting somewhere and is just short of running. The trail bent around and started up a valley. My body warm once again, I slowed on the climb and, just as I did so, came around a corner of the trail and almost ran into two day hikers. I was a little disoriented, but managed to cough up something that sounded like "Well" in response to their question of how far it was to the pass. It was only after I had left them (which was almost as soon as I met them) that they thought they were going to hike to Howse Pass. I looked at my watch. It was almost 3:30. I had worked hard for nearly 9 hours to get to here and thought it unlikely that they could make the pass, and come back, today. I should have warned them about the trail, but had not thought of it. Indeed, they were the first people that I had seen since the mountain bikers near Field. The first people in 2.5 days. The first people in about 110 K. My mood darkened as the sounds and smells of the front country began to filter up the hillside. I had crested over the ridge at the head of the minor valley and was now heading into the teeth of one of the prime front country attractions along HWY 93: The gorge of the Mistaya.

Located perhaps 100 meters, downhill, from a parking lot off the side of HWY 93, the gorge is stunning, but perhaps rather commonplace as well: A powerful glacial river is forced into a narrow canyon. The increase in water pressure makes the river appear turbulent and energized. The water action wears away at the canyon walls, polishing them into smooth, surreal shapes as softer parts of the wall wear away around the harder ones. It is like any other canyon of its type in the world. From my perspective, there was nothing much to see here. However, I was in the minority, it seemed. A pair of sweaty men, holding hands, wandered up the trail toward me for a better, ariel, viewpoint of the canyon. Red faced and huffing, they seemed to be enjoying themselves. Kids ran around the bridge over the canyon, chased and screamed at by their nervous, worrying parents. Teenagers lounged, trying to look cool and disinterested, along the cliffs of the gorge, well beyond the warning signs. Families, motorcyclists, bikers, lovers, haters, and me. It seemed the whole world was standing in Mistaya Canyon. After my solitary experience of the last three days, this was just too much. Most people seemed to be having a good time. In fact, I seemed to be the only person in a foul mood. I hurried up hill, my eyes on my feet, ignoring the greetings sent to me by various families on their way down to the parking lot. I did not belong here, and that was a problem for me. Never had I felt more alone amidst a group of people than I did on the short hike over the canyon and up and into the parking lot. I had devolved into something else, into something different from the people around me. I felt as lost as a pilgrim from ninth century Spain would have felt in a Walmart in Johnson City. I felt pity for those around me, compassion for their, in my eyes, wasted lives. I was glad that I was not them, and that I was now sitting in tall grass next to a busy highway, rather than sitting in the front seat of an RV with satellite TV and my choice of cold beverage. I was glad that I was me, even if the Buddha said that there is no such thing as Me. I hoped that the people were happy in what they were doing, but I suspected that they were not. They were going through the motions of what culture had told them was the path to happiness, but whether or not they found it, or even could find it, was a matter for themselves, not for me, or for culture to decide.

I walked slowly along the highway in a stooped shuffle, not even bothering to try for a hitch. I didn't want one. I didn't want to talk to the people in the RVs and trailers. I didn't want to answer their questions or try to explain why I was out here. I didn't want to convince them that I was not a dangerous vagrant. I didn't want to tell them that I taught calculus during the off season and that I enjoyed going to the opera. Let them keep their preconceived notions of me, and let me keep my, equally bigoted, mine of them. Everyone will be happier in the end. The crossed the bridge over the North Saskatchewan river and shuffled along, with Solzhenitsyn in my head again, to the Crossing. To one of the most hideous things that I had come across this summer.

The Crossing was an oasis for cars and RVs and trailers and buses and tourists along HWY 93. There was not much between Banff and Jasper townsites and few were the places that such things and people could rest and eat and not move for a while. The Crossing held numerous gas pumps for the things and cottages for the people, along with a large central building for trinkets, souvenirs, and food. A display of the SnoCats that people ride in on the Columbia Icefields tours abutted the building. Well fed, pink tourists stood about in clots eating icecream and drinking sodas and I tried my best to give them a wide berth, given the stink that was coming from my body (noticeable even by myself. Although much dirt and salt had been washed from my person after my morning and afternoon in the Howse, an oily accumulation of funk clung to my body and there was no reason to expose others to this. A lone hitchhiker stood near on the shoulder of HWY 93 with his thumb out, heading north. Given the size of the main building, I hoped for a good resupply point. What I found was a store filled with the stock and trade of the tourist business and little for a hiker. The restaurant was so unappealing, and overpriced, that I declined to buy a hot, cooked meal. I settled instead for a liter of chocolate milk, a liter of ginger ale, and a large bag of tortilla chips. There was enough food for a monotonous resupply, but it would cost. An oatmeal bar cost $1, and I needed three per breakfast. A 290 gram block of cheese, half the amount I would normally buy, cost $5. I found the ubiquitous ramen noodles and some macaroni and cheese and stocked up on lots of candy bars. The only good deal was a 450 gram hunk of summer sausage for only $2.69! They didn't even have peanut butter, let along Nutella. I filled a basket with five days worth of food and walked over to the one register that took credit cards (the others were cash only) and stood in line behind people buying fancy bottles of maple syrup and T-shirts with First Nations designs. The sight of me seemed to briefly startle the clerk at the register, but she quickly recovered, apparently unused to seeing people like me in The Crossing but knowing what I was doing. She was probably a hiker who worked in the area so that she could also play in the area.

Slowly a line built behind me as the clerk scanned each of my items. A few other clerks came over to help some of the people in line and I heard whispers of trips they were planning for the near future. Places that I, too, would be going to shortly. I said nothing, but inside thanked them. A sign hung by the register saying that everything had to be bagged before it could be taken outside of the building. I pleaded to be allowed to take things out in the basket and, after a brief conference with a managerial type, they agreed to walk me outside where I could repack the supplies and return the basket. No reason to waste the bags.

The hitchhiker was still waiting, patiently, for a ride north. The sun had come out and I staked out a position on the far fringe of the complex where I could sit in the shade and hang my sleeping bag, tarp, and ground cloth, wet from the previous night's condensation, out to dry in the sun. I could also watch the hitchhiker and his progress and would out of the way of the tourists of The Crossing, though not out of sight (which meant I had to keep my wet clothes on). Barefoot and reclining on my sleeping pad, I set into the chips and milk and soda before beginning the repacking of my food.

I sat and rested for more than two hours. The hitchhiker had not moved. He had gotten two nibbles, it seemed, one from a taxi and another from a diesel pickup hauling a trailer twice the size of an one bedroom apartment, but had not taken either. My pack was heavy again, although not uncomfortable, and I began the walk down HWY 93, stopping to talk with the hitchhiker. A grizzled old man with crooked, and missing, teeth, he was a delight to talk to. He had spent three weeks camping, illegally, on the shores of Lake Louise, far from the thousands of tourists that flock to the area. I didn't have to ask what he had done for the three weeks, as I knew already. Tiring of Lake Louise, he was heading to Jasper for a change of scenery and didn't know where he would go from there. I told him about my trip and he didn't feel the need (indeed, he knew) the reason why I was out walking. He had been trying to hitch for about four hours now, and the two nibbles that I saw were the only ones that he had gotten in that time frame. One was heading to the Columbia Icefields, about 50 K to the north, but he had not taken the ride because he didn't know how the hitching would be there. The taxi had offered him a free ride to Jasper, but he hadn't taken it because he was unsure of the driver. And so we stood by the side of the road, each understanding the other, each equally reviled by the people driving by. "Tourists just don't give rides to hitchhikers," he said, "only locals." He didn't seem put out by the lack of ride. He had all the time in the world to wait and was a patient man. I wished him luck and set out down the sunny road in good spirits.

I had only gone about 5 K down the road, and was beginning to look for an access point down to the nearby North Saskatchewan River, when a mini-SUV pulled off along the shoulder in front of me. Inside was a dirty, sweaty man who offered me a ride. I hopped in the SUV and off we sped down the road. He had been in my position a few hours before after finishing a day hike and no one had given him a ride back to his SUV. Although I was perfectly happy on the road, I took the ride and was equally happy. He was only going to the Rampart Creek campground, 5 K north, which would do for the night. He dropped me off at a campsite along the river and left me for his own campsite and friends. Standing on the banks of the campsite, I faced the question that many distance hikers face: Pay for accomodations in a front country campsite (hard ground, $13), or move into the woods and camp illegally (soft ground, free). I chose to pay and sleep on the hard ground, for no particular reason, other than I felt like having a picnic table to sit on.

After a meal of ramen noodles I turned into my sleeping bag, which sat underneath my tarp on the edge of the tenting area, which was too compacted to drive stakes into. Just as I did so, a warden drove up in a pick up truck and came over to tell me to move my tarp onto the tent site. I pre-empted him, still in my bag, by telling him that the tenting area was too hard to drive stakes into. He nodded, grunted, and left me alone, in peace and quite once again. I opened up Conze, who had finally gotten off the mythical origins of Buddhism and was now presenting selections from texts whose primary mission it seemed was to try to inform the reader of something useful. It didn't matter what it was, I thought. I was learning on my own, I was following my own path, and this, according to the Buddha's last words, was a good thing to do. I was reading to help me find the path, but it was I, and not the printed words, that would have to find it. It was I, my Self, that would walk the path, that would lose the path. My Self, that was not supposed to exist in reality.