The Crossing to Jasper

July 28, 2004

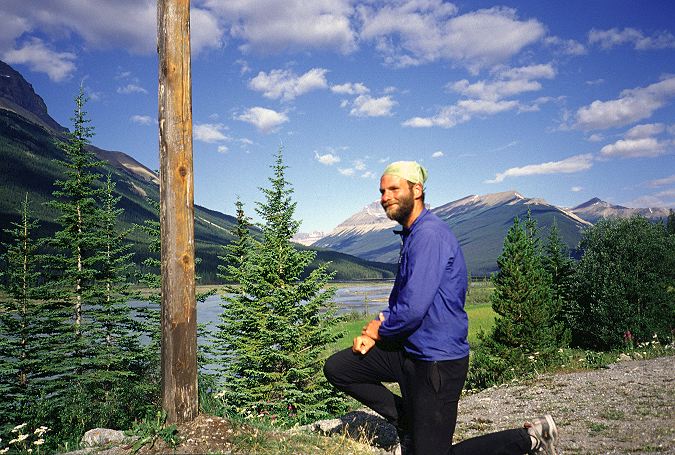

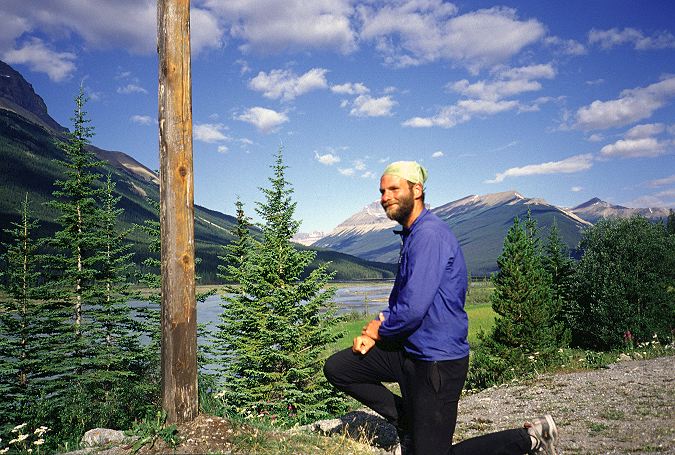

Even on the hard ground, I slept deep and long, not wanting to rise to face the road ahead of me. The cold air must have had something to do with it. There was even a layer of frost on the tarp this morning and I was thankful for the hot tea that I slurped down along with my oatmeal bars. It wasn't until just before 9 that I finally walked out of the campground and began the trek down HWY 93. Tourists just don't get up early in the morning and the usually busy highway was practically deserted. Every few minutes a car would rush by, disturbing my mornings thoughts, but mostly I was able to lose myself in the pleasant land: The North Saskatchewan River on my left, big mountains to my right and directly ahead. The mountains, however, seemed to be of a different sort than usual and reminded me of those in the Grand Canyon area. Utah, even. Eroded buttes and columns. Strange formations that people call The Temple of [blank]. Or, [Blank]'s Amphitheater. Rather than pondering some point of Buddhism, I instead concentrated on geology, something I rarely do. The strange formations in the Grand Canyon were caused by water: Softer rock was worn away by a river, leaving only the hard core behind. Perhaps the valley I was walking in used to much higher? Or the mountains lower? Less likely, this second possibilities. For once I actually wished I was carrying a natural history guide to the area.

As the morning wore on toward noon-time, the traffic on the road picked up, with every second vehicle an RV or a tour bus, making a direct line for the Columbia Icefields and, north of there, Jasper. Tourism seems to be especially popular with Japanese and Koreans, as numerous buses were marked solely in the characters of those two far-off lands. I picked my way through a few bushes to get to a secluded spot overlooking the river and had a good rest. Walking on a road is a long, sometimes dreary proposition. Normally, that is; HWY 93 is scenic enough to let the mind play and forget the asphalt. A few meters ahead of me I saw a small tree quaking, but there was not enough wind to make it move so violently. I knew what I would see long before I saw it. Off to the side of the highway, at the base of the tree, was a yearling black bear scratching himself on the tree. I stopped and looked at him for a moment. Unconcerned with me, he kept scratching. I vaguely threatened him, mentioning my cooking skills, but still he scratched. It was like looking at a tame house cat, even though this one had rather more bite than he normal kitty. No wildness left in it, nothing left that made it any more special than any other domesticated animal. I shook my fist at the yearling and kept on walking down the road.

I passed a famous ice climbing location called The Weeping Wall and simply had to laugh. In the winter time, the trickle of water coming down the sheer rock wall forms excellent and obscure columns of ice and presents ice climbers with something of a challenge. In the summer time, however, the wall had a few damp spots on it and looked as impressive as the backside of a barn. I was in a good mood as I could see from my map that I was nearing the end of my road walk: The Big Bend in the North Saskatchewan, away from which I would climb a few hundred meters and reach the Nigel Pass trailhead. From there, I would be back on trail for the next few days through Jasper National Park. Traffic on the road increased to a solid column and, as I started on the climb up, became almost a traffic jam as slower cars and RVs plodded up the hill side. I cut across a field, bypassing much of the Big Bend, and climbed up a short, but steep hillside to regain the highway near a scenic overlook parking area. Cars filled the lot and tourists wandered about, a little unsure of what they were supposed to be doing. I tried to figure out what was so scenic that it rated a parking lot, but could not figure it out. The valley holding the highway was spread out far below, and in the distance there were several waterfalls but, on the whole, there was nothing special here. Except, perhaps, that a parking lot could be built. I hopped over the barrier meant to keep people away from the edge of the drop off and had a seat, ignoring the herds milling about. I was struck by how happy I was that I wasn't in a car or a tour bus. That in a few minutes I would be back on trail and have most of Jasper to play in. I didn't have any reservations for campgrounds, but I was not overly concerned. Except for Marvel Lake in Banff, most backcountry sites were empty. Near the end of my current resupply leg, I would be traversing the Skyline trail and would have to take precautions not to camp where wardens might find me, but that was still a few days off.

The trailhead for Nigel Pass was located just a few hundred meters down the highway from where I rested and I took the opportunity to take another rest with my dinner. The sun was out and I needed to dry the (previously frozen) condensation from my tarp and fluff up my sleeping bag. Lazing by a river, I again reflected on how fortunate I was, about how perfect everything seemed at this moment. Sitting by a small river with pretty falls close by, no one around (despite the loads of cars in the trailhead parking lot), and a warm sun on my face. It would take me only a couple of hours to reach the first campsite in Jasper. I might stay there, or I might move on. Not having a fixed schedule was delicious.

After my ramen noodles, and feeling very refreshed, I began the gentle climb up toward Nigel Pass, out of ear shot of the road and, indeed, any sign of the road. The only hand of man seemed to be the trail I was walking on. The trail would alternate between short forest walks and open avalanche slide areas, where I could once again gaze upon the distant mountains, knowing that my route would take me close to them. I would once again be in the high alpine that I had left when I descended to Field on the Ottertail. I had truly enjoyed my time on the leg between Field and The Crossing, but that was a different, empty land. I might (would) run into other hikers now, but I would do so in an area that was supposed to be near the pinnacle of outdoor wonderlands. I scanned to the east to see if I could spot the route that Lynx describes in his guide book, but saw only silver mountains. Not grey mountains. Actual, gleaming silver mountains.

I was heading directly for a gap in the silver mountains, although it was so low as to hardly warrant calling it a pass. I was gently gaining altitude through the meadows and occasional stand of trees. Without realizing it, I had made the pass. Below me was a river, that could only be the Brazeau. To the east was the GDT route. All around was heaven. Except for the quickly darkening skies.

I loped down to the river and a sign indicating that I was now in Jasper National Park. I rock hopped across the river, changed my mind, and returned to the middle where there was a large rock on which I could rest. Looking up river, toward the east, the GDT route looked like it might be difficult not too much further away. And fun. Interesting mountains, but difficult river fords, according to Lynx and my maps. Sometime in the future, I thought. With friends.

The skies were forming as I picked up the trail on the other side and climbed into a barren land composed only of rock and dirt. I tried to find any example of local vegetation, but could come up with only a weed or two growing between rocks; a few patches of lichen coloring a grey boulder red; some plucky shrubs hugging the ground, trying to hide from the scouring wind. Lovely, absolutely lovely. Even the skies could not hurry me from this place.

Winding around through the land, I was constantly bombarded with the thought, "This is the most beautiful place in the world. There is nowhere as stunning." It must been the tenth or twentieth time since leaving the US that I had thought that. I thought it many, many times on the PCT. And, I would think it many more times in the future. Jasper was putting on a show for my first trip in, showing off her wares and strutting, flaunting, luring. Where were all the tourists? As nice as the view from HWY 93 was, a few hours of fairly gentle walking would have taken them to a place more wonderful than anything they might see from their car. They had already paid to get their cars into the park, so coming up here would be free for them. They might have to pass up one front country attraction to do so, but it was worth it. Some bread, cheese, and a bottle of wine would make for an excellent few hours surrounded by the land. But, there was no one here, except for myself and a few rodents scurrying about.

The pure rock eventually gave out as the ridge that I was on dropped toward a deep, green valley holding Boulder Creek, my home for the night. Somewhere, buried in the forest below me, was an official campsite. I stopped, yet again, to sit on a rock, for no other reason that I wanted to. I didn't want to come down just yet. Perhaps I should camp up here? I could walk back to Brazeau and get water for the night. Surely I could find some flat ground on which to sleep for the evening and I doubted that any one was behind me. There were no bugs here, there were no tourists or other backpackers to disturb me. If it cleared, I might even get a good sunset, should I prove able to stay awake until 10:30. Alas, the skies were not good. Rain was coming, and probably within the next two hours. There wasn't a good place, protected from bad weather, where I could put up my tarp. No, the valley would have to do.

I dropped into the valley and crossed Boulder Creek on a bridge into the campsite. Yuck. There were four other hikers already set up, although there spots didn't look particularly appealing even against the dirt patch that was left for me. I scouted through the area looking for a feasible place to camp, someplace that would not act as a collection point for water. Some place that had a nice, soft bed of needles and black, loamy earth. Not a place that was rock hard, except for the inch of loose dirt. I found places, but for some inexplicable reason I returned to the dirt patch to pitch my tarp. I suppose I was afraid that a warden might come by and, seeing me camped somewhere unofficial, want to see my permit. In truth, there was no good reason to return to the dirt patch. I should have hiked on and stealth camped. Instead, I pitched in the dirt. The crummy, lousy dirt.

When I stepped into the patch, a cloud of dust sprung up like a geyser and in the few short minutes it took me to set up, both myself and my gear were coated in dirt. I carefully put out my ground cloth and sleeping bag to try to keep them from getting to dirty, but this was a losing battle and eventually I gave up and went over to the cooking area for some desert and journal writing. A group of four backpackers came in and I directed them to some of the clear areas I had found. I was still amazed that I had camped in the dirt patch, particularly as I knew it was going to rain tonight. Mosquitoes buzzed about, mostly ignoring me and my DEET covered skin. The other occupants of the campsite ignored me. When the rain came, twenty minutes later, I ran into my tarp for cover. The rain and wind came in with a fury and for thirty minutes I huddled in my tarp, hoping that I wouldn't get too wet. Puddles of water formed about me. Rain came down the mosquito netting, but the bathtubbing I had done with my ground cloth kept it from running on to me. As the rain let up, the cold front behind it descended into the valley, forcing me inside my sleeping bag; I even had to read with my hands inside my bag to keep them from going numb with cold. Why did I camp here? Even a randomly chosen spot would be better than this place, yet Parks Canada was charging people to stay in it. Bastards. Just as I had vowed never to leave good trail for bad, I vowed never to stay in a bad campsite again. Feeling sufficiently self-righteous, I read some more Conze, which served, along with the softly falling rain, to put me instantly to sleep.

It rained on and off through the night, but by the time the sun came up the skies were beginning to clear and I found myself camped in a muddy mess. The outside of the tarp was wet with rain. The inside was wet with condensation. And everything was covered in dirt. Very carefully I got out of my bag and retrieved my food bag. Because I had been unable to buy tea at The Crossing, I had to use one tea bag for 3 cups of water, resulting in a very weak, but hot, brew. Packing up, without getting even more dirt on my gear, was challenging, prompting more curses in the direction of Parks Canada. Big puffies floated by as I hit the trail at 7:30, glad to be moving again and generating body heat. I very quickly reached Four Points Campground, which seemed world's better than Boulder Creek, which has to rate as one of the worst I've ever found. However, it seemed that Boulder Creek was filled to capacity, causing me to worry that I might have difficulty in the near future. Stealth camping might become necessary even if the upcoming campsites are nice. Just as I started to get into a good train of thought about cause and effect, I started wheezing. Legs burning. The trail was heading uphill with an Appalachian Trail like grade. However, unlike the AT, I knew that there would something good on top. I was heading for a place called Jonas Pass and, above that, something called Jonas Shoulder. I had never climbed up to a shoulder before. After 300 vertical meters the forest began to run out and I emerged into the alpine. Directly infront of me was a broad, long pass. Like Citadel or Goodsir, Jonas pass was more like a slopey plateau than a mountain pass.

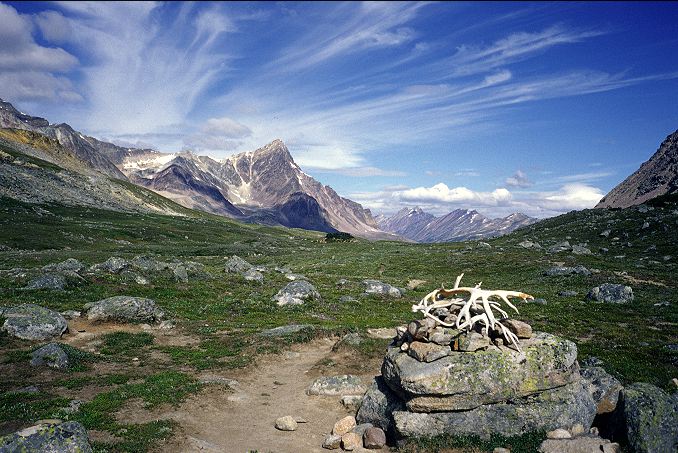

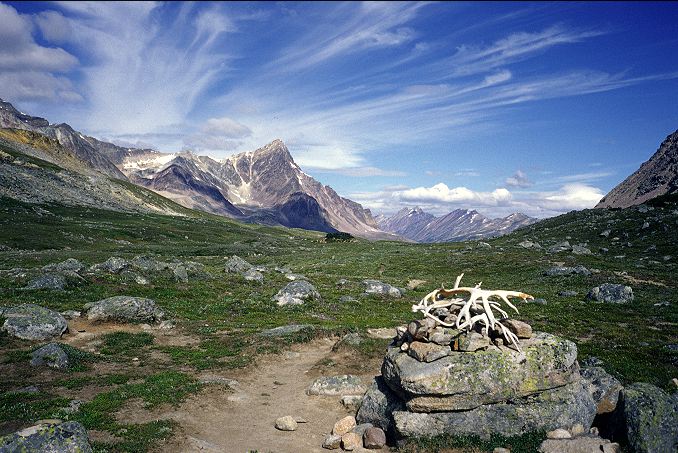

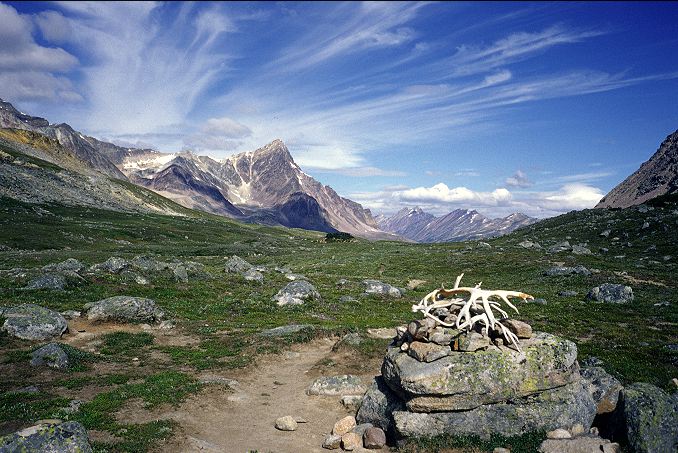

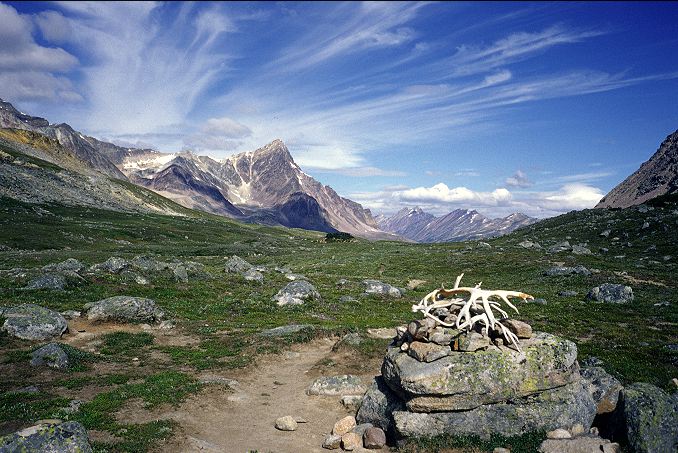

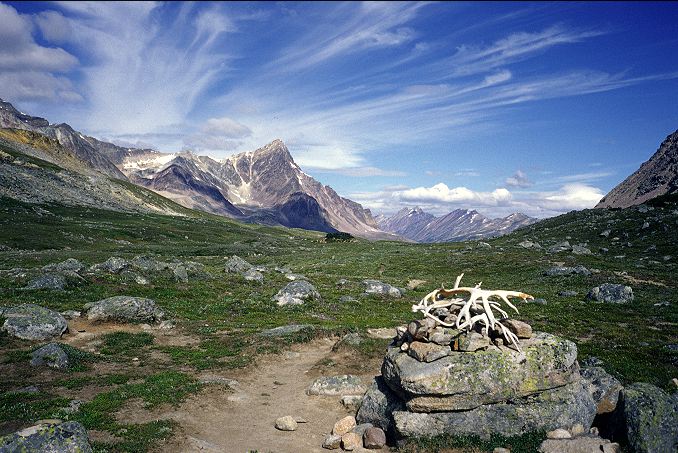

Winding slowly up toward the pass, all my frustrations with Boulder Creek were gone and I was again transported into that most beautiful place in the world. I had been there yesterday afternoon before dropping down to the creek and the camp, and I was back once again. I cannot help but think that a life spent immersed in beauty is somehow good for the soul, good for the spirit, good for the Self. Buddhists deny the existence of these things and so would disagree with me on these points. Alpine flowers spread out along the green carpet of grasses and shrubs, all low and hugging the ground for protection from the wind. Glaciers sat and stared down into the valley, clinging to the slate and tan colored mountains lining the pass area. Almost out of the blue, I reached the official pass, marked with a cairn and a set of antlers.

Lovely, but it was unclear why this was the pass, and not any of the points within a hundred meters of it. It was all flat and level and perfect. Even the clouds twisted themselves into funny shapes, with odds bends and spurts, wisps and blocks. If I were a competitive hiker, I thought, I would be able to stop my hobby, knowing that there was no where else I could go that could rival this place (forgetting about yesterday, of course). Strolling down the valley in the sun I passed a few backpackers on their way up toward the pass. They had come from Maligne Lake, where I was heading tomorrow and had been enjoying their time in Jasper immensely. I could understand already, despite the awful Boulder Creek. I left the hikers and climbed off trail a few meters for a rest and some privacy. Two backpackers came by, but did not see me on my scrub covered hillock. Spread out below me was a deep valley running off toward, most likely, the valley holding HWY 93. I was not going to follow it. Instead, I'd climb up the wall of mountains on my right, breaching them at something called Jonas Shoulder. Then, down to the valley on the other side.

Clouds were whipping by at a great rate and I thought that I should probably make it over Jonas Shoulder, my last high point for the day, before there was any chance of a lightning storm. Along I wound, hugging the right side of the valley and slowly gaining elevation. A group of four backpackers came down the trail from the Shoulder and asked, expressively, if I had seen the bear. What bear? They were dumbfounded that I hadn't seen it. "But, we've been staring at it for thirty minutes on our way down!" I didn't remind them that what they were looking at was behind my back, and instead expressed some sort of remorse. The trail began to climb seriously and sweat broke out onto my forehead and arms. Slowly I trudged up the side of the mountain, switchbacking occasionally, but mostly just plowing into it. The valley floor dropped off beneath me, rapidly, and more mountains began to rise up on the other side of the Shoulder. The wind picked up as I neared the top and reached something approaching that of a tornado at the top. With the wind and the chill, I had planned to keep going down the other side, but it was just too pretty at the top not to stop and lounge for a while.

I could see most of the land that I had traversed since leaving the antlers and Jonas Pass. Everything on my level was rock and sand and dust and unlife. Below me was the lush valley. On the other side the icy mountains. My wind shirt and pants and bandana began to hum with the wind like they hadn't since LaCoulotte Ridge. LaCoulotte? Wasn't that the prettiest place in the world? The view on the otherside of the Shoulder was just as lovely and I could see, more or less, my afternoon hiking: Down to the plateau and run the valley down, down, down. Lots of switchbacks, completely open, and, hopefully, a lot of treeless trail.

After taking pictures, I sat around, despite the wind and the cold. Just sat. Nothing more, nothing less. The perfect break, without a soul around, despite being in the high season of hiking in the Rockies. I had seen eight backpackers earlier, but now that I was up, it was fairly clear that there were no more within a few hours walk. I was glad that I was alone up here, but I was surprised that more people didn't come into the area. Given the size of the campgrounds that I had passed, Parks Canada clearly were anticipating that more people would use the area. But the people didn't come to the land, to this magnificent places. Perhaps Canadians were lazier than Americans, although that would go against every stereotype. Perhaps Canadians didn't like to backpack. That didn't fit in with the Canadians that I knew. Maybe it was Parks Canada itself, its policies and requirements. Maybe the Canadian people would one day get tired of being hassled over accessing their own heritage and they would sack the entire department or bureau or ministry or whatever Parks Canada was classified as. Perhaps they would put the National Parks in the hands of BC Parks, which actually seemed to know what it was doing and why it existed.

I sat on Jonas Shoulder for as long as I could before the wind dropped my temperature too low, and after a half hour had to start scampering down the other side of the Shoulder, switchbacking gently down toward a small rivlet and the plateau I had spotted from above.

Being able to see in all directions is comforting, and I was not terribly happy when the trail began to run down toward the trees as it descended into the deep, glacially carved U-shaped valley. Clouds were mounting, once again, as is massing their troops for a rainstorm. If I wanted to eat out of the rain, I would have to do it quickly. Jonas Cutoff campsite was significantly better than Boulder Creek, but it was swarmed with mosquitoes. I started my daily ramen cooking and spread out my gear, taking the time to smother my face and hands in DEET. The mosquitoes, I had found, could bite through my socks and so I had to keep my feet covered with my rain jacket or risk a mild chemical burn if I wanted to DEET my ankles under my socks. There was enough sun, with the relatively dry air, to get my sleeping bag and ground cloth dry, but my soaking tarp was only partially cleared of its moisture. Rain was coming and so I packed up quicker than usual after eating my dinner and set off for Poboktan campground.

The trail ran mostly through the forest and there wasn't much in the way of grand scenery, but I was enjoying myself immensely. The clouds parted and the sun came out, its light filtering down softly through the forest canopy, like morning service in a cathedral. More similarities between the two settings occupied my mind for the walk. These were certainly not original thoughts, as Abbey and Muir and Powell and King and Thoreau had all written as much. Was I thinking this because I had read what they wrote, or because I was seeing the same things they had seen, felt what they had felt. I was tiring physically and I wasn't sure why. It wasn't that I was exhausted or sore or breathing hard. Indeed, the walking was mostly flat or barely downhill. Everything in my body was working just fine. But, for some reason I didn't have much energy. I was eating plenty and was getting enough water, which usually prevents lethargy. As composed as my mind was, my body was somewhere else, a condition that one can definitely feel and is even more definitely distracting. Eventually, my mind would begin to feel the effects of the lethargy and this would impact my hike in a most negative way. I hoped that it was simply general fatigue from the long summer, as this could be cleared up by some rest in town. I was glad to arrive at Waterfalls campground and take a sit.

The camp was one of the nicest in the national parks that I had yet come across. Most official campsites in the Waterton and Banff and Jasper were absolute dumps, where no one would ever camp if the decision was left up to them. Waterfalls was different. Located on a cliff next to the falls of a large flow, the roar of the water crashing against the rocks was just loud enough to be charming, without being intrusive. The camping pads were spacious and looked relatively comfortable. Views could be had off the cliff edge along Poboktan Creek (which the falls flowed into) and the mountains in the distance. My mountains tomorrow. And, there was no one camped here. A solitary man sat at one of the picnic tables eating some lunch and looking over his maps. I joined him at the picnic table to chat for a bit. He was on a trip from somewhere in the south up to Maligne Lake and was taking the same path that I was. Maligne Lake was the southern end of the Skyline Trail, which was supposed to be the most popular backpacking trip in Jasper (and probably all of the national parks). He had a permit, but wasn't keeping to it, and for good reason: There just wasn't anyone out here. We talked about Jasper and some of his other ramblings in Jasper, a place that he loved. Originally from Germany, he now lived in Edmonton and got out to the Rockies as much as possible. At the end of a long list of the glories of the area, he had a bit of bad news: The warden's had told him that the bridge over the Maligne river might be out. This was decidedly bad. On the map, the river looked fairly large. If it was even close to the size of the Poboktan, a ford might prove rather challenging. I didn't understand why the warden's didn't know for sure. Couldn't one of them just walk out to the river and see if the bridge was still there? We looked over alternate routes. If the bridge was out, he would walk back upstream and see if he could ford near the river's source. I was planning to walk to the where the river met Maligne Lake, and then swim the lake itself. Mine was the more foolish, but faster. Confidence of youth, I suppose.

We were both heading to Poboktan campsite for the night, but my summer-conditioned legs and small pack left little doubt as to who would arrive first and get the pick of campsites. I wasn't expecting anyone else, given how many I had seen on trail recently, and hoped for a lonely site tonight. I loped down the trail through the pleasant forest, bordered by the glacial body of Poboktan, and again pondered the religious overtones that streaked much of outdoor writing. Commonality of experience sometimes indicates a true vision. Other times a mass delusion. I wanted to believe that I was seeing truly, but there was nothing concrete, as in mathematics, that I could use to logically analyze this thing. I could only, as it seemed the Buddhists did, directly experience it and hope for the best.

I crossed a log bridge over a stream and arrived at Poboktan campsite to find it empty, but with several containers strung up in the bear wires. The campsite was another good one, right on the glacial creek. I hadn't passed any non-glacial water sources, but didn't mind drinking the silty stuff. In fact, I found the glacial milk to have a peculiarly sweet taste that I liked. There were four spaces for tents, each with a sign, and one that had no sign. It seemed to be the flattest and best drained, so I pitched my tarp there, ignoring the fact that it was I wasn't supposed to, and quickly put my gear out in the sun in hopes of drying it a bit more before the sun went behind the mountains. With the proximity of the creek, and the absence of bugs, I scrubbed out my windshirt, T-shirt, thermal shirt, and socks in the creek and set them out to dry as well. The buckets in the wires drew my attention and I dropped the cables down to see what was in them. Two were full with various bits of junk, the other two empty. The bear wires in the Canadian parks didn't have hooks where you could attach your food bag. Instead they had metal loops. Because I wasn't carrying a carabiner, I had to tie my bags onto the loop with a bowline and then haul them into the air. While this wasn't a problem when they were nearly empty, it was when they were relatively full: The wires didn't come down to the ground and I had to balance the bags on one knee (thus standing on one foot) so that I could get enough slack to tie them on. The buckets in the air disposed of this problem for me and so I was glad to find them, even if some were filled with trash.

My chores done, I ate desert and wrote in my journal for a while, and then tucked into some more Buddhist writings. The German rolled into camp about forty five minutes after I did, and immediately asked where the water was. A little stunned, I pointed to the river just three meters away. "No, I never drink glacier water," he said. Shrugging my shoulders, I wished him well on his hunt for a spring. He dropped his pack and departed on his water hunt. I returned to Conze for a while, but by the time the German had returned, thirty minutes later, my maps were out instead and I was plotting my assault on the Skyline. Which campsite might have the fewest number of campers, and thus be the safest for me to use? I tried to think like a 10 K a day backpacker, but this was really rather hard, as I was used to covering 40 K in a day, at a leisurely pace, and still being in camp by six. I pondered one place, then another. Perhaps a stealth camp would work best of all. Then, the simple solution occurred to me: Camp just before the Skyline, and then hike the whole thing in a day. There was a campsite on the fireroad that led up to the real start of the Skyline, and surely no one would camp there. It would mean that I would cover 45 K, but this shouldn't be a problem, no matter how steep the trail might be. Being popular, it was probably well marked and I wouldn't spend anytime with navigational problems. That would put me in Jasper the morning after. Lovely.

Satisfied, and with my logistics solved, I retired to my tarp to read a bit more. I was coming to realize that I didn't really need the reading, nor was it, perhaps, the best way to proceed metaphysically. Experience reality directly, not through spoken words or printed words. A Zen phrase that came up in one of Conze's selections seemed to confirm this: The practice is Enlightenment. A perfect thought for tomorrow.

It was actually only semi-cool in the morning, which greatly aided my desire to get out of my sleeping bag. I still made a full pot of weak tea for warmth and strength at set out at 7:30, with the German still asleep, snoozing away one of the best parts, for me, of the day. I was heading for Maligne Pass and the route seemed to be a duplicate of yesterday's climb up to Jonas Pass: Steep forest walking, followed by a gentle, broad valley void of trees. The classic alpine, but so plateau like as to hardly warrant the name Pass. I wasn't complaining. Jonas Pass and Shoulder were, at least yesterday morning, the most beautiful places in the world and a repeat was not something to be dreaded.

The pass went on and on and on, which suited me just fine. If I could run this pass all the way to town I would be a happy kid indeed. Alas, I finally reached the small pond that marked the pass (a pond at the top of a mountain pass?) and knew that once I left this place, the rest of my day would be literally and figuratively downhill. That meant a mandatory sit by the lake, on top of a small, scrub hillock.

My feet propped up on a rock and the sun on my face, I ate some summer sausage and a Snickers bar with my eyes closed. I may have drifted off to sleep, or I may have simply lost my stream of consciousness for a while, as when I opened my eyes I had the sensation of having missed out on a few minutes of the time swirling around me. The sun was still warm and the pond was still blue. The mountains hadn't gone anywhere and I was still on the hillock. I closed my eyes again and did nothing for a while longer. I just was, and was without.

When the time came for me to depart from the pass, I did so with a little sadness, and with a little hope. The trail sloped gently downhill heading toward the woods once more. Not until tomorrow morning, when I started on the Skyline, would I again get into the alpine. Bugs and much and a possibly nasty ford were awaiting me in the valley, experiences that I would rather avoid. However, if I wanted the Skyline, I had to do get there first and my step quickened as I entered the forest on the valley floor.

A few typos in the guidebook and on trail signs caused me some distress, but little else happened until I happened to look up from my shoes and saw a family of four heading in my direction. My surprised look was mirrored on their faces, and it took us both a few seconds to compose ourselves. I had seen few people since Jonas Pass (the German), while they hadn't seen a soul in three days. I didn't bother to ask about the river ford, as if they had gotten across it the bridge was either in tact, or the ford was manageable. We swapped recommendations for the future before continuing on our separate journeys.

My afternoon lethargy returned once again and it became difficult to hike. My body just didn't seem very interested in seeing what was around the next corner. Pessimistically, it recalled the Appalachian trail, which was easily countered by my Mind shouting out that no one was around. I began to take breaks every thirty minutes, rather than every two hours as I normally did. A nice tree with a bit of shade would do. Or, a funny looking flower. Eventually the trail left the forest as it struck the plain holding the Maligne. Even the pretty land couldn't restore vigor to my body and it became the responsibility of my mind to drive my body forward, which cut out any sort of contemplation that I might have engaged in during the long afternoon hike.

I reached the Maligne and found scant evidence that a bridge had ever existed. This was something of a mystery as usually a washed out bridge is deposited somewhere in the area of the flood plain. Perhaps it was quite a deluge that cleared out the man-made structure. The Maligne was clear and slow, and shallow, barely up to mid-calf on me. It would take a warden about two hours to walk out here, and another two to walk back, to find out if the bridge was actually washed out. If they were tired, they could ride a horse up. Even on foot, they could leave after breakfast and be back by lunch, but it seemed that there were more important things to do in the front country.

I forded the Maligne and walked a few hundred meters into the forest on the other side for shade and yet another rest. What was wrong with me? Physically, I could point to nothing in particular. It was just my motivation that had up and vanished. Another 30 or 45 minutes and I would make Trapper Creek and stop. I hoped that a longer-than-usual campstay might breathe some strength into me and forced myself to start walking once more. The trail began to fade in and out and I lost it several times when it ran through a meadow, or a swamp. Small troughs of standing water were found here and there, and usually I could manage to avoid getting my feet wet. However, at one point the trail, or, what was left of it, ran across a small creek and, putting my left foot onto what appeared to be solid ground, I sank in above my ankle in mud. A bit perturbed, I took my foot out and put it in the stream to wash off the solid red mass that clung to my foot, obscuring all sight of my shoe. A minute of soaking brought off the rest of the mud and I crossed to the other side to find the trail. While hunting for it, my other foot, the right, went in above the ankle in another mud pot. Back to the creek, in which I stood for two minutes, battling the mosquitoes and washing off my shoes. A huge deer fly flew into my ear and, in the process of killing it, I squished it up, which meant that for the last twenty minutes of hiking, I had to defend myself from the mosquitoes as well as pick bits of fly out of my ear.

Trapper Creek, at least, was not a complete dump. Perhaps not the best of campsites, but acceptable and with a good water source, although it was also swarmed by bugs. It was only 5:30, yet all I wanted to do was to go to close my eyes and go to sleep. Or power hike for another 15 K and reach the alpine again. I decided to stay with the bugs and my solitude. I quickly lathered in DEET and put up my tarp while water for couscous was heating. I gulped down dinner and attached half a flat of raspberry newtons. I had four of the cake-cooky jammed into my mouth when out of the corner of my eye I spotted something coming up the trail from Maligne Lake, something human. A man with a day back was walking up, with a ID badge on a necklace. "I was hoping to run into someone here," he said. I took a look at the badge and the picture did not seem to be his. Nevertheless, we were only 5 K from a road, so he might be a dayhiker afterall. "What is the fastest way to the lake?" I managed to choke down the newtons and told him that he'd have to walk back to the lake on the trail that he came in on. "But we've been following the river for a long time now," he proclaimed, not seeming to believe me. I wanted to make short work of this conversation, so that I could get back to my newtons, and so pulled out my maps and pointed to the campground with my middle finger and the trailhead with my little finger, without speaking a word. He looked at his compass and then at me, and then at the compass again, finally understanding. It turned out that he and a friend had day hiked up to a mountain in the area and thought that it would be a good idea to bushwhack straight down the hillside, cutting off a kilometer or two of trail hiking. They had no maps and had gotten turned around by the creek. He scratched his head, thanked me, and set off in the correct direction of Maligne Lake. I returned to my newtons with happiness.

The bugs were too much to stand, even covered in clothing and DEET and so, upon finishing desert, I hung my food in the wires and crawled under my tarp. I had to kill 48 bugs that had followed me inside before I could get some peace. Close to my record, I thought, of 60 at Howse Pass. I was worried that there was something wrong with me, as the last two afternoons had seen rather extreme lethargy, which usually doesn't strike me. It could be the forest walking, I thought, I hoped. It could be a sign that I had taken on a parasite during my summer. I had drunk most of the water this summer straight from the source, rather than treating it with iodine (which I was carrying for emergencies), trusting that I would be able to recognize a good water source from a bad one. My confidence might not be justified. Tomorrow I'd be in the alpine all day long, so if the lethargy returned, I could rule out the forest syndrome. I went to sleep with hope, but not with the serenity of other nights.

As I went to sleep at 8 pm last night, I awoke at the very early hour, for this summer, of 6 am. It was very cold out, however, especially while sitting on the open-air composting toilet. I brewed strong tea, having reserved three bags for today, and ate breakfast, all alone at Trapper Creek. It looked like a beautiful day was in the works, which was important to me as I would be in the alpine for a long time today. By 7:15 I was rumbling down the trail and saw how the dayhikers had gotten confused with the stream. The trail down to Maligne Lake runs upstream for about 1.5 K before rounding over a ridge and heading down hill. The dayhikers must have come down through the woods and hit the trail and followed the stream, quite naturally (without a map, that is), down hill and intersected the campsite where I was staying.

The quiet forest was good for contemplation and I thought, as I did most mornings, of some of the fundamental questions of Buddhism. First, everything except Nirvana and Space was conditioned. That is, everything else had a cause, and thus was not independent and subject to decay. However, mathematics (i.e, pure logic) does not seem to follow this. For example, the Pythagorean Theorem (which relates the length of one side of a triangle to the lengths of the other two sides) stems from a few simple axioms. It makes no statement about the physical world. It is only a mental exercise to prove the theorem and it just so happens that our universe, at least locally, obeys these axioms. What are the causes of the Theorem? It seemed that the causes had to be the axioms and logic. If you removed these, was the Theorem false? That is, if no sentient being knew the axioms or the proof, was the Theorem no longer valid? It seemed to me that this was not the case, that logic remained and was independent of people's cognition of it.

What of the idea that removing the causes of an event also removes an event? On the surface, this seemed self evident: Remove the glacier above Cairnes Creek, and the creek would disappear as well. However, some simple physical examples deny this. For example, one could take a radio out into space and transmit a signal. A radio wave would go out into the vacuum of space and would continue to travel on forever, until acted upon by some outside force, even if the radio was destroyed. The direct cause of the radio wave was gone, but the wave was still there. However, one might extend the notion of the causation of the wave to include the Universe itself, and if the Universe disappeared, the wave would have to as well.

A bend in the trail, a pretty meadow, Life rolled by at 5 kilometers per hour as I was lost in thought. What about Karma? How does it act if there is no permanent soul or conciousness? If there is nothing concrete for negative actions or thoughts to stick to, how do they slide from life to life? Without a permanent Self or a superstructure to the Universe, it didn't seem possible. Perhaps, however, there is no re-incarnation in the simple sense. Perhaps there is only one life and the physical change of death is simply like waking up from a dream each day: Consciousness continues as one long, unbroken being, with only its physical characteristics changing over time. This would negate the need for a Self or for a superstructures, but the texts that I had been reading did not seem to mention this. The idea was for death to enter, a soul of sorts to depart the body and be reborn in another physical being, along with all of its negative (and positive) Karma.

I found myself in the parking lot for Maligne Lake standing next to a few trash cans and wondering why. A few cars were in the lot, with some backpackers getting ready to start the Skyline and I decided that the time for contemplation was over for the day. Now, I was going to hike, and only hike. After dropping some trash in the bins, I started up the Skyline, walking past the warning signs that told me to turn back, as I did not have a permit for the trail. The trail climbed gently up hill and I passed six wheezing backpackers with heavy loads on the way up to Evelyn Creek campground, which was one of the nicest that I had seen in the national parks of Canada. I sat by the creek and scrubbed my dirty socks on a flat rock in the creek, waving the backpackers as they came up. A few tents were still up in the campsite, despite the fairly late hour of 9:30, the owners sitting on picnic tables after finishing their respective breakfasts. I continued up the trail, climbing gently on numerous switchbacks, toward Little Shovel Pass. I re-passed the six backpackers rather rapidly, and then another two, as the trail lifted me out of the forest and above treeline into the alpine zone.

Climbing higher and higher, the trees became few, and those few were stunted, at best. This place was clearly not hospitable for most of the year, but I was moving through on a sunny, warm day, despite the howling wind that greeted me as I neared the pass.

Never had I worked so little for such rewards. I could have rolled myself up the trail to Little Shovel pass in a wheelchair and yet, once up, the scenery was of the sort that finds its way into calendars and promotional shots for SUVs. Mountains, valleys, glaciers, passes, flowers. All were present in this land, along this most popular of trails.

I descended from Little Shovel pass, saying hello to the various marmots and pika that shrieked at me as I strolled down, meeting a mother and son hiking southbound, both with huge grins on their faces despite the sweat on their brows.

I dropped into a small ravine which held a quiet brook before climbing out and on to the plateau between Little and Big Shovel passes. The plateau extended for quite some distance and there was nothing to obstruct the views in all directions, except the heavy mountains in the distance that rimmed the area. Big Shovel Pass, a small notch, was in view, several kilometers away. The plateau began to slope gently upward, which provided some perspective on the ground that I had just traversed.

I walked through Snowbowl campground, which was another stunner, set in once of the only groves on the plateau. I left a note for future GDT hikers in the campground register before setting off toward the pass, admist long meadows filled with pretty alpine flowers, struggling for life in this exposed land, trying to get all their growing and procreation done before the coming winter would bury them for most of the year.

I stopped to rest in a flower patch alongside a stream, enjoying the sun and cheese, not caring that my black pants were quickly coated in sticky yellow pollen. I was so filthy that a little pollen might actually improve my general appearance and smell. Following the pattern of almost every afternoon, there were not thoughts in my head or contemplations or obscure points of philosophy. I was simply sitting in a flower patch, eating and resting, watching the stream go by. The greatest disruption I faced to my tranquility was an occasional gust of wind, spread the pollen of the patch across the plateau. Big Shovel Pass was not far above me and a short walk though more meadows, sloping uphill would bring me to a few switchbacks up to the pass itself. There was no need to rush, no weather to hound me, no deadlines, dates, schedules, or other constraints upon life. There was only here and now.

I hauled myself out of the flowers and thirty minutes later stood on top of Big Shovel Pass, astounded with what I saw. The Skyline had been mostly green so far, with small trees and shrubs, and plenty of flowers. North of Big Shovel the land was bare rock, with hardly a trace of vegetation, beyond supersaturated lichens, to be seen. Indeed, the lighter shade of the trail provided the one of the few contrasts with the dark red and brown rock.

Why the abrupt change? Big Shovel Pass went over mountains that were not particularly formidable and I couldn't see why there was such a rainshadow. Perhaps some old volcanic event had scoured the land on this side of the pass. The trail remained as gentle as ever, and the thought of someday doing a thru-roll, in a wheelchair, seemed rather possible, although I am sure that Parks Canada would disapprove of people bringing wheeled devices into their Domain. The trail ran alongside the flanks of the mountains, with far Curator Lake, shimmering blue, in the far distance. I passed three day hikers, which seemed somewhat improbable given our distance from a trailhead. Still, they had microscopic days packs, too small even for ultralighters. Perhaps a base camp somewhere? I downed two King Size Snickers bars that I had saved from the leg from Field to the Crossing, fueling up with more than 1100 calories of fat and sugar for the climb up to the Notch, as the pass above Curator Lake was called.

A deep valley split off to the left of Curator Lake, running, for sure, down toward HWY 93 and Jasper. Hikers who could not get permits for the Skyline faced the unenviable possibility of following a trail down into the valley and a forest walk into Jasper. There was no way I could do such a thing at this time, permit or no. If the wardens wanted to fine me, that was a just price to pay to be up here. I arrived at Curator Lake to find two women sitting by its banks, resting before tackling the Notch, or perhaps after coming down from it.

I had planned to rest here myself, but did not want to disturb their zone and so began the steep climb up to the notch. Perhaps 400 vertical meters above me, the Notch had a narrow, precarious looking trail leading up to it and it looked like there was a snowfield right on it. Distant figures could be seen high up, just below the Notch, moving very slowly. I moved slowly myself on the only steep climb thus far today. My idea of a thru-roll was dashed, as I doubted I could get a wheelchair up the narrow, rocky, and steep trail. There were places even when I had to be careful with my footing as the trail had begun to erode away. It seemed that the trail was not cut into the mountainside due to the loose rock and the path was more of a climbers route than a trail: A long history of boot tracks wore a path into the flank and provided guidance for the hiker, rather than a trailbed. That was fine with me, but I could see why the people above me had been moving so slowly: It would be bad to fall here.

Curator Lake dropped beneath me as I gained elevation. I could see all the way back to Big Shovel Pass, and even, I believed, to Little Shovel and perhaps even Maligne Pass. It was all so wonderful that I began to worry that the top of the pass would be a let down. Sweating hard now, but without breathing too hard, I slowly worked my way up to the Notch, losing and gaining the bootrack, and eventually, skirting the snow field, reached the top of the Notch. The entire world to the north opened up and I lost all sense of perspective, all sense that there might be some other place to compare the Notch to.

To the north I could clearly see the town of Jasper, along with HWY 93 and an ugly scar of a ski resort cut into what used to be a forested mountain side. The awesome mountains of the northern Rockies spread out for me, with a large white pyramid probably being Mount Robson. The end of my hike, then, was visible, yet I was still more than a week away from it. Further to the south were clustered the huge peaks of the Columbia Icefields area. Most of the high summits in the Rockies are in the Icrefields area, with the notable exception of Robson, which stood on its own, aloof and without lesser sentinels.

Three packs were sitting just off the trail, and it took some time before I was able to spot three hikers on a small peak above the Notch. I contemplated heading up myself, but everything was so great from the Notch that I simply sat down on the rocky ground, my pack acting as a pillow, and gawked like a tourist. I suspected that I would experience no lethargy this afternoon.

The hikers came down from the peak, with one of them proving brave enough to come over and talk for a while. I must have presented a truly awful appearance, but when the hiker heard my tale he seemed to understand. After resting for half an hour and soaking in the land, I set off just behind the three hikers.

The Skyline was up and intended to stay up, running along flanks and ridges in an attempt to keep hikers as high and exposed as possible for the greatest length of time. In bad weather, this place would be scary. But today the sun was shining and there were only a few clouds in the sky, and the only fearsome thing was the prospect of dropping into a valley. Below and to the left was a land that suggested many off trail hiking possibilities due to the lack of trees. Parks Canada would probably frown on it, but I didn't really care at this point. Open, magnificent, stunning, complete, perfect, dreamy, Edenic, I lost myself searching for adjectives.

The Skyline rumbled over barren, seductive Amber mountain and my brain finally retrieved a memory with which to compare the Skyline. On the PCT, there is an unbelievably scenic stretch from Kennedy Canyon, near the 1000 mile mark, to Sonora Pass that gets up, stays up, and provides memories that never fade out. The Skyline was as close as I'd come to finding a place that matched the PCT through Sonora pass. Indeed, it might even exceed it. I passed one group of backpackers on a break, and then another, declining to say hello or even acknowledge them, not wanting to break my feast. I hoped they would understand.

From Amber Mountain the trail began a very slow descent toward the valley that held Tekarra campground, which presumably was at the base of hulking Mount Tekarra. Below me the trail switchbacked like crazy, dropping only a few vertical meters for a hundred walked. I passed a few more backpackers and those above me were on the move again. Signs everywhere warned hikers not to cut switchbacks, as it tended to cause erosion of the trail. I would have ignored the signs and headed straight down the easy hillside, something I rarely do, but declined as it would probably set a bad example for those above me. Besides, there was no rush at all.

I slowly reached the valley floor and skipped over the small stream than was issuing forth from the head of it, greeting two tired looking hikers but not stopping. I just couldn't bring myself to stop. I had to keep going, to see what was ahead. I rumbled along the plateau, moving through a few small stands of trees, until I finally reached Tekarra campground. Huge and spacious and really well set, it was barely occupied. I thought for a moment about staying here for the night, but there were twenty some-odd hikers behind me, all of which were planning on staying here and probably had permits. I settled onto a picnic table and started water heating for Ramen noodles before spreading out my sleeping bag and ground cloth to dry in the sun. Few bugs, gorgeous mountains, and a pleasant creek made this place special and I was honestly surprised that Parks Canada allowed people to camp here. It seemed that they usually picked inhospitable sites far from attractions. Not on the Skyline, though. This was someone's baby, and they wanted visitors to come away with only great memories.

I polished off my noodles and was eating desert when the hikers I had passed near Amber Mountain began filtering into Tekarra for the night. I still had plenty of juice left, something they found astonishing when they found out that I had started on the other side of Maligne Lake this morning. I was traversing the Skyline in a day, while they were taking three. Some chalked it up to my (relative) youth, others, undoubtedly, to some sort of machismo. On my part, I couldn't see how they could start hiking so late, and stop so early, given how grand the land was. Each of us considered the other a little off and were convinced of our own correctness when I crossed the creek via a sequence of rock hops and set out for Signal Mountain.

The trail climbed briefly through a miniature forest before gaining the side of an open mountain where all could be seen once again. A particularly savage looking chain of silver mountains dance in the distance, giving me more thoughts for a future hike, although they looked brutal enough that a hike in them would be more like an extended climb.

I rolled through the open hillside and started to think about stealth camping on top of one of the rounded knobs that I saw above me. The weather was good, if windy, and I doubted that anyone would hike cross country to find me. I would be visible from the trail, however, but it was even more unlikely that anyone would be out hiking now, or before I left in the morning.

I stopped to fill my waterbag from a small stream and thought about the possibility. The only real downside is that I would have to stop hiking through this place, even if it would mean saving something special for tomorrow. I just didn't want to stop. I wanted it all, and I wanted it right now. No, I would continue on to Signal Mountain, which hopefully would be as nice as Tekarra. After my rest, I happened to pass two hikers coming from Jasper and heading for Tekarra. They had nothing but bad things to say about Signal Mountain, but I was committed now to finishing the Skyline.

Just before dropping to the fireroad that marked the end of the Skyline (at least, the end of the scenic part), the entire valley north of Jasper was visible. I could even see the route that the North Boundary Trail would take toward Robson: A big gash of a valley to the north ran straight through the mountains. It didn't seem very far from Jasper, but I knew that distances were distorted from my vantage point up high and it might be something of a haul to get to the start of the NBT and the beginning of the last leg of my summer trekking. It was a rather sad thought and I tried to forget about it as I straggled into Signal Mountain campground for the night.

I was greeted with a swarm of bugs and an unpleasant campground. I would just as soon have camped in the parking lot of a mall. The concrete would have been softer, probably, than the compacted gravel that formed the tent pads. There were some hikers here already, but there was plenty of space for me to put up my tarp and, after talking briefly with a few who were interested in my rig, I dove underneath the bug netting. I set a new record for killing, with 71 bugs falling prey to my fingers and the walls of the tarp. One group of hikers even packed up and left for the trailhead, too disturbed by the bugs to stay the night, despite their tent. One of then slipped me a few candy bars on their way out and wished me luck on the last leg of my trip to Robson. In my sleeping bag, I reflected on the day. The Skyline was simply the most fantastic, easilly accessible short trail that I had ever been on. Its magnificence could not be captured in words, at least by me, and I couldn't imagine coming to Jasper and not hiking it. It could be essentially day hiked by anyone in reasonable shape, so permits were not much of an issue. I read some Conze, but could not follow it: My mind was still on the Skyline, my eyes still seeing Amber Mountain and the twin lakes and the northern Rockies, rather than a page filled with rather sterile seeming words. I was tired, but I was happy and not even the hard ground could take away from that.

I awoke feeling more tired than when I went to sleep. I had had a sequence of powerful and unique dreams (when have you ever had a unique dream, one never experience before?) combined with the emotional highs of yesterday to force an illsleep upon me. I was physically tired as well. Not just weary, but exhausted. I needed some downtime and luckily Jasper was not far. I might even be able to get a lift into town from the trailhead, rather than having to walk for another two hours along a mountain bike trail to get there. I didn't imagine that I would be able to get a motel room in Jasper and hoped that one of the local campgrounds would have a shower and some quiet space in which to rest. Otherwise, it would be stealth tonight. I rolled on down the fireroad, bypassing what seemed to be a short cut trail that was more direct, if it went. At the bottom not even a great surprise could lift me back to normal spirits: My first Great Divide Trail sign.

I managed a small laugh at my first, and only, sign for the trail that I had been hiking for the past few weeks. Since I had been booted out of the Line Creek mine area I had missed the only constructed section of trail outside the national parks, where the trail was not named anyways. In conversations with Dustin Lynx, the guidebook author, I had learned that the GDT had several different northern terminii, ranging from Jasper to Mount Robson, and the author's own preference of Kakwa Lakes, north of Robson. I sat on a bench and rested, wishing that Jasper was closer than two hours away. No ride was to be had, so I had to walk the mountain bike trail instead. Every step was forced, every swing of my arms tiring. I rested as frequently as I could, at one point in the middle of the fireroad, which almost caused an accident with some mountain bikers who, quite rightly, did not expect to find a bearded, filthy, disheveled person sitting in the middle of their track. I apologized and they went by, seemingly happy that no one was hurt by my foolishness. I skirted the edge of a golf course and thought about borrowing (stealing) a golf cart to take to town.

I continued, however, on foot and eventually reached the Athabasca river and a jumping off point for raft trips. I had been in the wilds for so long that the appearance of hundreds of tourists beat me into a bloody mental pulp. I tried to close my eyes out to them, but the sounds of kids laughing and running about, and parents chasing them, still came through. I hustled out of the area, crossed a bridge and reached HWY 93A, which was quiet and still in comparison. The town of Jasper, however, broke this. Like being in a mall at Christmas time, it was simply crowded. I hated crowds, at this point, and my mood became darker and darker as I felt surrounded and confined. Diesel engines rattled down the street towing massive trailers. Fat, pink tourists strolled about eating icecream, looking bored and complacent. I needed a place to hide, and settled on a park bench in front of a McDonalds. I was hungry, but didn't want to go into a confined place smelling as I did: My smell bothered me, and I was used to it. My hunger finally got the better of me and I hoped that the tourists would be able to forgive my intrusion upon their senses while I stood in line. I left as quickly as I got my food: Two double quarter pounders with cheese and a large strawberry shake. Returning to my bench, I hoped no one would talk to me or even acknowledge me. I just wanted to be alone with my food which, despite not having eaten civilized food since the cafe with the pretty waitress in Canmore, tasted foul. The shake, however, was nice and satisfied my craving for dairy product.

After finishing my food on the bench, I felt a little better and worked my way through the throngs to the Parks Canada office, where I hoped to find a little refuge and some information on the NBT. I left my pack outside and found the inside to be somewhat empty. I talked with a helpful warden about the NBT and he even xeroxed a few pages of a guidebook for me! He even offered to drive me to the trailhead tomorrow! It was a long 52K roadwalk (although along rough, gravel roads) to the trailhead and his ride would help immensely, even if it meant not taking much rest in town. I couldn't believe my luck, but when he mentioned that tomorrow was a civic holiday and thus the post office would be closed, my luck crashed back down. I had maps waiting for me in the post office and thus would have to take a zero day and find a different way to the trailhead on Tuesday. I told him that the bridge over the Maligne was out, but that it was an easy ford, something he took note of. Whistler's campground, outside of town, had plenty of walk in spaces and a hot shower and he advised me to take it and not even try the motel thing. We talked for a while longer before the office started to fill and he had to work again. He was the first helpful warden I had run into during the summer (John and Chad, the trailcrew workers in Yoho, were not wardens, but very helpful) and I was sad to leave him. I bought some postcards on my way out and wandered over to a laundromat to wash clothes for the first time since leaving Calgary.

The laundromat had internet access, but no bathroom to change clothes in. I managed to talk the clerk into letting me change in a utility closet, rather than stripping down in public, but in mid-undressing the manager came over and wanted to boot me out. Explaining what I was doing, he let me finish; he was just worried that I might hurt myself in the jumbled closet, which was perfectly valid as their were many sharp tools laying about and plenty of open electrical boxes as well. I apologized, finished, and started my laundry going, sitting about in my underwear and rainjacket. I drank a coffee while waiting and checked email, but mostly I just waited under the stares of the other clotheswashers.

I was able to change into my clean clothes in the video store above me (owned by the same manager) and felt moderately better, despite my oily, stinking body. I bought some supplies for the night at the grocery store, including a newspaper, and a bottle of whiskey from a women in something like a sports bra at a liquor store, and began to head out of town. I stopped at a Subway for a sandwich before pushing my way through the tourists of Jasper on my way to HWY 93A. The highway provided some open space and walking along it was really very nice, as it ran along the banks of the Athabasca. Whistlers campground was about a 30 minute walk away and cost me $19 for the night for a walk in sight, something I would have objected to had they not had hot showers. I found my campground and put up my tarp, before retiring to the comfort of a tree for afternoon cocktails and the newspaper.

I read and drank coke-whiskey for a few hours before making my way over to the shower and scrubbing myself clean as best I as I could. I had purchased a small bottle of shampoo to use for soap, and my underwear acted as a washcloth. Smelling fresh and with all the built up grime removed, I felt born again. The weariness of most of the day was gone, at least in part because I knew tomorrow would be a true zero day: Eat, resupply, try to find an easy way to the NBT trailhead. Eat, eat, and eat. Maybe buy some fuel. Read another newspaper while eating in the expansive park outside the Parks Canada office. Maybe eat a half gallon of ice cream. Hopefully find an AYCE buffet. I went stayed up well past dark to see the stars come out and went to sleep happy and content, safe in my $19 home-for-the-night.