Jasper to Mount Robson

August 2, 2004

I slept late into the morning, which for a distance hiker means 8 am, thanks to the whiskey and the stars the night before. I packed up my gear and headed into Jasper for some breakfast, making sure to pay for another night before leaving. I didn't want to leave my kit sitting around in the campsite all day and so I had to haul it with me. All 14 lbs of it. It looked like it would be a busy day at the campground, as an entire busload of some kind of European kids were waiting around for campsites. HWY 93A, as expected, was empty of cars at this early hour and provided for a pleasant walk into town. I had spotted a good looking breakfast place the day before and hoped to be able to get an American sized meal for a change. Even though the town was empty, everyone that was in town had the same idea that I did and there was a lengthy line of seniors, kids, and other tourists waiting to get in for a big meal. I'm sure they needed the extra calories. Not wanting to wait for food, I walked around the corner to a hotel that had an All-You-Can-Eat breakfast buffet and spent an hour stuffing as much sausage, bacon, ham, hashbrowns, eggs, muffins, cinnamon rolls, and pancakes into my belly as possible. I waddled out of the hotel feeling full for one of the first times on the hike. I definitely got my $7 worth out of the place.

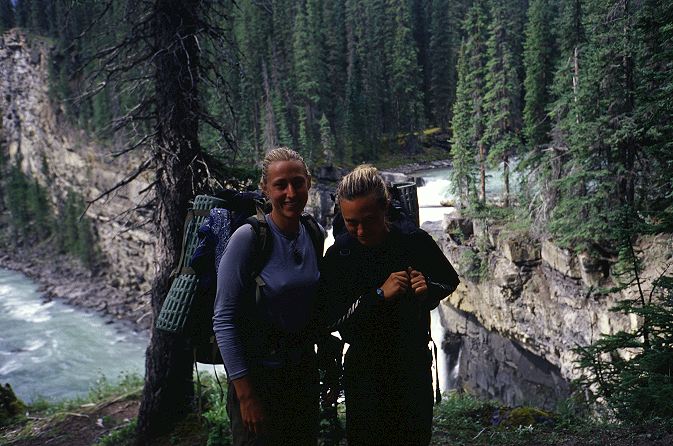

Now that I was full for the next few hours, I could turn my attentions to something other than eating, like drinking coffee and reading the newspaper. I added a half gallon of orange juice for good measure and retired to the park surrounding the Parks Canada office to drink my coffee and OJ and read the paper for a while. A tree provided a backrest and the soft lawn was a pleasant break from the dirt and dust of the trail. Canadian papers are much like American papers, only with more news about Canada and less about the US. Still, I flipped the pages, occasionally reading the words, but mostly looking at the people around. Various types walked through, including some with backpacks on. However, these bore the unmistakable markings of the weekend backpacker: Too much gear, too heavy footwear, nervous gait. I lounged about, occasionally shifting my position near the base of the tree to keep in the shade, glad that I didn't have to hike anywhere today. Out of the corner of my eye, I noticed a change in the surroundings. Two pretty women carrying packs were walking across the lawn to the Parks Canada office. With small packs. And running shoes. Dirty and grimy, with greasy hair, they had all the markings of distance hikers, including the soft, mechanically perfect stroll. No wasted energy. Perhaps these were the GDT hikers that I had been following since Waterton? The engineers had told me there were four or six of them, rather than two. I returned to my paper and coffee.

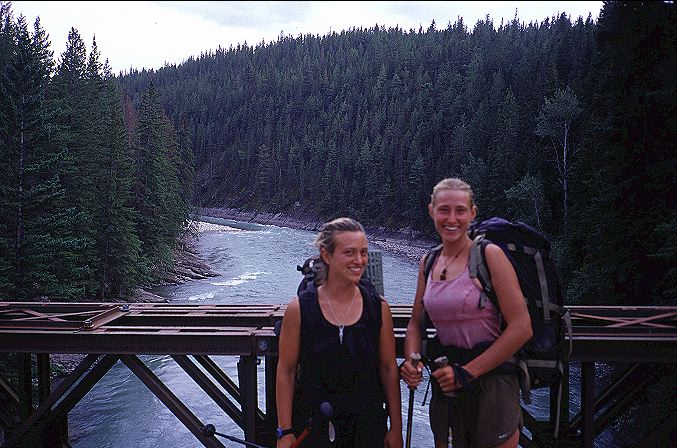

An hour went by and I found the pretty women sitting under a tree ten meters away from my tree. I looked over at them and they looked back, giggling. One asked me what I was doing here. I told her that I was going to hike the North Boundary Trail. "No, I mean how did you get here?" I confessed to having walked here from the States, which brought more giggles. They had done the same. I hopped up and moved over to their tree to meet the first GDT hikers that I had come across this summer. Daris and Paula were both in their mid 20s and from various points across British Columbia. Both were veterans of the PCT and Paula had also hiked the CDT. It took about 2 minutes for us to become friends. Our stories from the trail were shockingly similar. They had been thrown out of Line Creek mine as well. They had barely made it across Cairnes Creek. They had skipped the Cataract Creek section coming out of The Crossing for the same reason I did. They had the same revulsion at Jasper that I had at first and even ended up having a pizza delivered to a back alley so that they could escape from herds. They were planning to finish at Robson, but were planning on taking the Guidebook's route instead of the NBT, as I was. They had spotted me as a distance hiker as surely as I had them. Weekenders rarely carry small packs and use trail runners. We sat and chatted as old friends for an hour, two hours. It was time to feed.

Across from the park was a bar and that seemed like a good place to eat and have a few drinks, so we removed our selves from the lawn and relocated to the smoky interior of the pub. Beer, stories, more beer. Food, beer, more stories, more beer. Although it happens frequently, I'm still amazed at how close distance hikers become in staggeringly short time periods. Daris and Paula had slept next to the trailtracks last night and were happy to hear that I had a campsite already set up where it might be a tad bit more quiet than the night before. Over the course of the afternoon and evening, we decided to hike the NBT together, particularly after I told them about the difficulties of the Colonel Pass area, which had burned a few years back and had not yet been recut. We stumbled out of the pub and headed for HWY 93A, hoping we might be able to score a ride rather than having to hoof it. After a stop at a convenience store for ice cream, an old VW bus pulled over and told us to hop in. The woman driving hadn't planned to go to Whistler's but seemed to understand the problems of hitching in a tourist town and gave us a lift anyways. Needless to say, she was a local and not a touron.

Back at my campsite we finished off my bottle of whiskey, staying up for the stars, before falling asleep in the quiet campground. I couldn't believe my good fortune to cross paths with Daris and Paula. I had apparently passed them when they had to hitch out of The Crossing to buy supplies, as the resupply box they had sent themselves to The Crossing had not shown up. I came through as they were heading back to the trail and was only a few hours ahead of them all the way to Jasper. If today hadn't been a civic holiday, I would have gotten a lift from the helpful warden to the NBT trailhead and missed the two ladies. Fate had intervened, and I would get to spend the end of my trek with two fun and interesting women, rather than all by myself. Fortune, indeed.

Breakfast was on our minds in the cool early morning and we left the campground well before our neighbors were stirring. Just outside of the campground two elk were milling about by the side of HWY 93A, apparently completely oblivious to the presence of humans. Might as well have been housecats. Jasper, at the early hour of 9 am, was almost empty of tourists and we found a table at an Italian place that also offered regular breakfast items. Bad coffee, average omelets, nothing special. I had to resupply and find more fuel, and we had to solve the problem of getting to the NBT trailhead. We could walk the 52 K, particularly as most of the distance was on a little used gravel road, or perhaps hitch to the end of the pavement, or perhaps get a shuttle from someone. I stopped in at Gravity Gear, the local climbing store, and explained our predicament to the amused climbers working behind the counter. They gave some suggestions and I left with a canister of isopropane and a list of names. The Parks Canada office had more names and the three of us talked over how much we could spend while waiting in line at the postoffice. I had a brief scare when they couldn't locate the box containing my maps, but the clerk double checked and found the box sitting right next to her, unscanned as of yet. I grabbed a cup of Princess of Darkness and sat on the lawn of the PO sorting through things with Daris and Paula. About $100 was all we were willing to pay, total, for a lift. Perhaps a tourist with a pickup truck felt like making a few dollars. Surely it wouldn't be too difficult to find a ride to a trailhead, even an obscure one like the NBT.

After sending my package back to Mark and Kristine's place in Calgary, I resupplied at the grocery store, and the Korean convenience store, we met up again on the lawn of the Parks Canada building and decided that we really needed to make some progress on finding a ride to the trailhead. Daris propositioned a few tourists, but everyone looked at her the same: Are you insane? Please don't hurt us! There they were, frightened by 5'4" 120 lb. Daris. I went over to the train station to ask one of the taxis there about shuttling us. Although very friendly, the driver didn't think he could get us to the trailhead. Even if he could, he thought it would run us at least $125, one way. Since he had to drive back, it would be on the order of $250. I thanked him and left.

I stopped into Parks Canada to file a trip plan and get a permit for the NBT which, since I had a Wilderness pass and was reserving less than 24 hours in advance, was free. The warden didn't want to list the permit for three people since I only had one Wilderness Pass (Daris and Paula had theirs, but they were outside), which meant we wouldn't be completely legal. I listed campsites with no intention of keeping to the schedule, and even at a relaxed pace the warden seemed unconvinced that we could hike the NBT in four days. He warned me and warned me, and even wrote the warning on the permit, but eventually handed it over and wished me luck, assured that we were headed for complete disaster.

The ladies hadn't had any more luck with tourists, so I walked back to Gravity Gear for more advice. I explained the high rates, which the climbers were rather disgusted with and found outrageous. They got on the phone and starting calling their friends to see if anyone was in town and could give us a lift. Alas, with the gorgeous weather, everyone they called, if not working, was out climbing or hiking. No luck. I milled about the front of the store, thinking of what to do, when Paula came up with good news: Jasper Taxi would take us, and it would probably only cost us $50. We even had two good hours before they would pick us up, so we could feed again and take our time in leaving.

Jasper Taxi came by at 4 pm and whisked us off to the trail head. Although the first few kilometers were along a busy highway, the taxi quickly got off onto a small paved road, running past an overflow campground, before hitting the end of the pavement and the start of the gravel. There were a few potholes, but even my low-slung Camry could make it in style. The land became more and more wild as we left development behind and all of us were a little giddy with excitement. Daris and Paula tried to make farting noises with their arms, but didn't have the knack. The driver dropped us off at the trailhead and wanted only $40, which I thought extremely reasonable, and left us to our own devices and a cloud of dust. After changing into short running shorts, the ladies and I were off for the last leg of our own personalized GDT hike, far from the Divide, but very happy that we were here.

None of us were under any illusions about the NBT. It was supposed to be low, flat, viewless, but very wild. Everyone we had spoken to about the NBT mentioned it with a sort of reverence. People just didn't hike it when places like the Skyline and Jonas Pass were so much more accessible and traditionally beautiful. This left the NBT to occasional horse groups and the rare hiker. The trail began as an old fireroad, and would continue as one for quite sometime. Originally, Parks Canada had built a road all the way to Snake Indian falls, a few kilometers to the north, but decided that it was too much effort to maintain it and closed it off to motorized traffic. Thick stands of old Aspen, replacing the evergreens of higher elevations, lined the pathway, giving a new aspect to our summer treks. Passing a stream, we stopped to cook dinner, hoping to avoid bear encounters in camp on our last leg. Daris and Paula had come into close contact with a grizzly sow and her cubs in Peter Lougheed. I had my close encounter on Goodsir pass. None of us really wanted any more encounters at smelling range.

The mosquitoes were incessant, swarming over the large amounts of skin that Daris and Paula were showing off in their short shorts. DEET helped, but I hid under my rainjacket for protection. Dinner did not last long and we were soon moving again along the old road, through the Aspens. For no reason whatsoever, the three of us decided, simultaneously, to stop hiking and camp in the middle of the trail. No one was coming, so why work for a campsite when we could use the (hard) road. I had trouble driving stakes in for my tarp, while the ladies had none: They had forgotten to bring the stakes for their tent when we left Jasper. At least it was a freestanding tent.

Bear bagging was more difficult, as we had stopped in one of the few places where the Aspens were non-existent and only small pines grew. I read a few passages of Conze to them before we quit for the night and surrendered to sleep, only a few kilometers from the trailhead, but almost sixty from Jasper. No tourists would disturb us, no trains, no cars, no RVs, no cell phones, no neon signs, no streetlamps, no trailers, no diesel engines, no waddling, pink, frightened, complacent tourists. Just the peace of the woods.

I slept well on the road, despite the hard ground, and woke early. No sign of stirring from the ladies' tent. I brewed a batch of extra strong tea, but didn't really need the caffeine for motivation this morning: I wanted to hike, to see what the NBT had to offer. I set off just as Daris and Paula emerged from their tent, knowing that they would catch up sooner or later. Despite the distance I tended to cover each day, I didn't have a particularly rapid pace; I just hike most of the day. I was in a contemplative mood and worked on refining the questions I had about the metaphysical system of Buddhism. Conze was skirting around the edges of the problems with the selections that he presented. Much of the reasoning that they used was based on analogy, rather than logical deduction. This, it seemed to me, was good way to point to what you wanted to establish, but a poor method for showing it to be true. For example, cutting off one's arm caused irreparable physical harm. By analogy, harboring anger would also cause damage to the soul: Ill causes ill, regardless of the setting. However, the physical damage has something direct and concrete to affect. Buddhists deny the existence of a permanent soul or Self, so what could a negative thought or emotion affect? Many of the selections led up to a central problem, then did not address is. There was a gap between the philosophy and the end-goal of Nirvana; what lay there was left unsaid.

I found myself at a pleasant creek and stopped to scrub out my socks from yesterday in the cold water, using a flat rock as my washboard. Daris and Paula came down the old road after I had finished and was reclining against a tree thinking about the differences between religion and philosophy, between direct experience and pure logic. It would be nice to think about something else for a chance, and the three of us started the slow climb toward Snake Indian Falls, the end of the old road, chatting about the Legend of the Hot Warden and his plastic shorts. Daris and Paula had actually met him near Elk Lakes and I listened intently to their tale. Not only had they met a warden (actually a provincial ranger) in the semi-backcountry (at a cabin on the road that I had walked in on), but they had met a strange one at that. Something to think about that was as far removed from obscure metaphysical musings as it is possible to get.

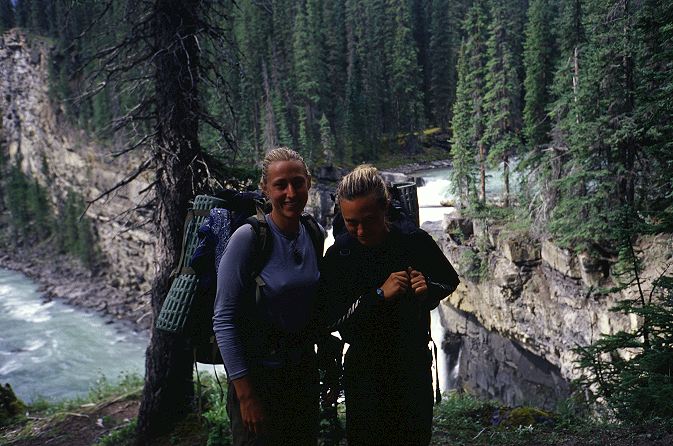

We reached Snake Indian Falls two hours later, climbing the barely noticeable grade, and had a sit on a cliff overlooking the impressive work of gravity and snow melt. While not nearly as high as Helmet Falls or Takahkwa Falls in Yoho, Snake Indian was broad and powerful, rather than thin and high, giving a notion of solidity and mass. Daris scampered down to the falls so that we could get some perspective on their size relative to her.

Below the falls were scattered the remains of massive tree trunks that had been swept down the river to the falls. This was the river that we would be following for the next day and a half to Snake Indian Pass. From there we would cross a valley and wind our way up to Robson Pass, and then the end run to the park headquarters, where Daris and Paula's parents would be meeting us. We lunched at the pleasant spot, basking in the sunshine, telling stories and just enjoying the company. The GDT had been a lonely trail, and I was glad to have company for the last part of it.

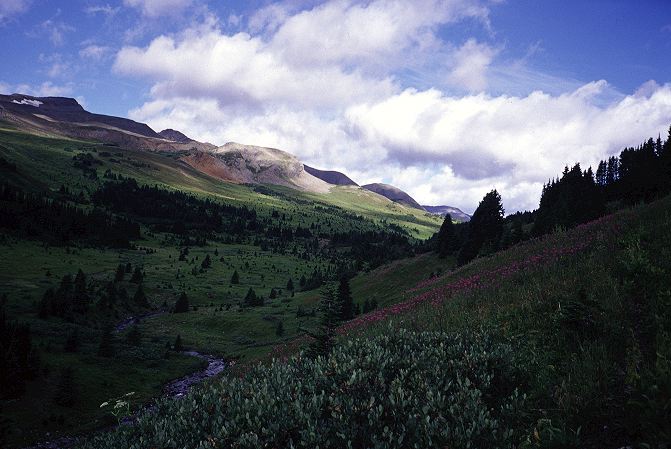

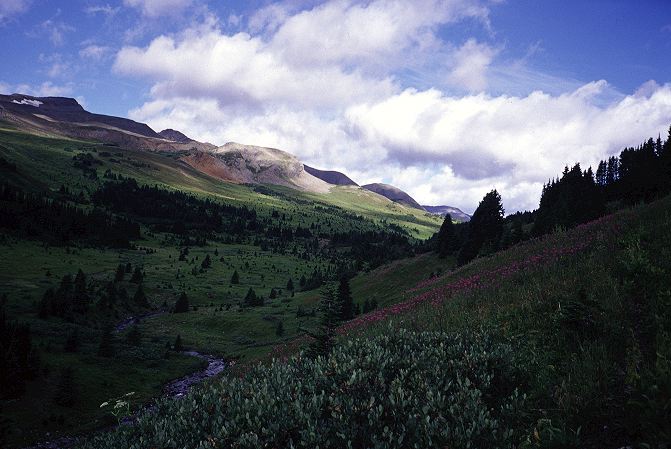

We separated for a while after the falls, each of us taking our own pace, just as things should be. On the PCT last summer Birdie became the perfect hiking companion, hiking at her own pace, stopping where and when she wanted, joining me at breaks or in the evening. Daris and Paula did the same thing. The NBT ran through forests and swamps, with minimal gain and with maximum ease. Although we were only a day out and were on an actual trail (despite its fading out occasionally), I had rarely felt like I was in such a wilderness. Northern British Columbia, in the Hickman area, was as wild as it got (for me or anyone, for that matter), and this was close. The world outside could have ended, and there would have been nothing to tell us, nothing to indicate that anything was the matter. The place was primal.

It wasn't the presence of rugged mountains or devastating glaciers or thin ridges or needle spires that created the beauty of the place. Rather, it was the place itself, its own quality, that shown through. Here, indeed, was proof that Things were not simply the sum of their parts, of their causes. The marshes were not beautiful. The shrubs were not. The rapidly growing storms clouds added little. Rather, it was the land taken as a whole that was special, not any single part of it. If each part had no special quality to it, how could they add up to something so marvelous?

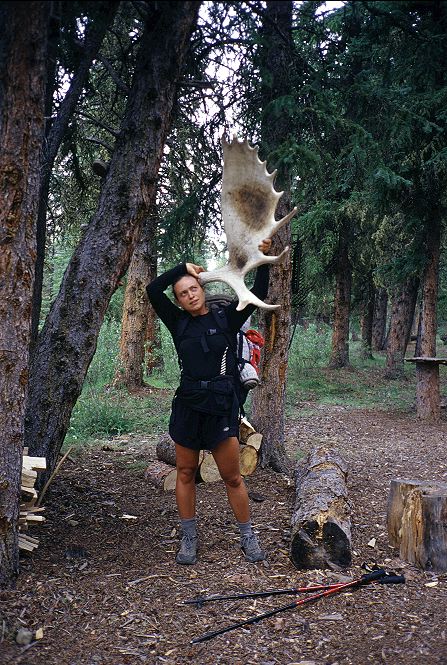

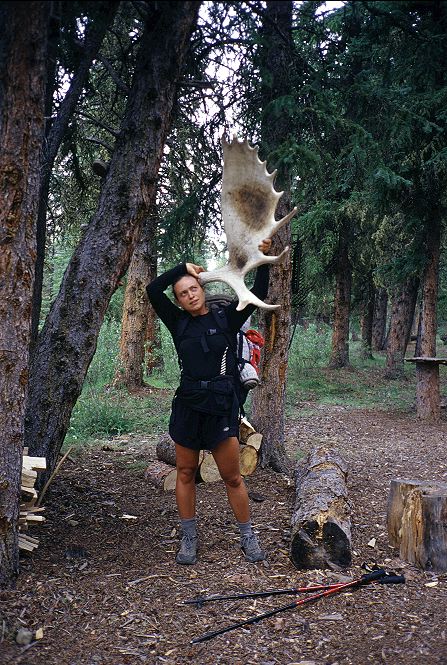

We rolled in, together, into a campground and pondered staying the night, but with the amount of daylight left, plus the coming of a storm, we thought we might hustle a bit further up the trail to Welbourne Falls, where there was another campground and a backcountry warden cabin. With any luck, a warden might be there (improbably) doing trail maintenance and invite us in and out of the storm that was sure to strike shortly. Near the edge of the campground we found numerous antlers and horns, including some large specimens from the Moose.

We reached the campground under malevolent skies and wandered about, looking for the warden cabin. The trail had gone from gross to well manicured as we approached the campground, so the cabin had to be somewhere close. Finally I spotted a trail leading through a swamp and we followed it into a clearing holding a large and newly stained cabin. No one was home and it was locked up tight with a rather impressively sized lock given the remoteness of the area. Were they worried that addicts from Commercial Street in Vancouver might wander by and try to steal something? At least it had a porch on which we could sit and rest and cook dinner out of the rain, which began to fall violently just as we arrived.

We found a good way to hide from the rain and relax, the rain driving away the mosquitoes, thankful that we did not have to be out in the downpour. I cooked a double helping of Lipton's Singapore Curry noodles, one of my favorites and not available in the US, and tried to stay warm while my pot bubbled away. The storm dropped the temperature significantly and I was thrilled when Daris produced a plastic bottle of Dr. Skipper which held some brandy inside. We took a few sips, for warmth only, and decided to save the rest for some other time, for some other people. The storm raged for almost an hour before it blew itself out and passed on, leaving nothing but sunshine and warmth once again.

After a bath in the creek next to the warden cabin, we sat about the porch chatting about nothing inparticular, and important things in general. Too lazy to walk over to the campground that the warden station abutted, we simply camped out in the warden's domain, hoping that no one would show up in the middle of the night and make us move on. Even with the foul weather at the end, the NBT was living up to the reputation that it held with those we had talked to in Jasper. There was something special about the land that did not come from classical alpine scenery, something that I had felt in between Field and Howse Pass. Life is so easy when you can go to sleep looking forward to Life the next day, rather than simply being a day closer to death.

The day dawned early and clear, with the excellent weather that followed yesterdays storm continuing into the morning. I got the ladies stirring around 7:15 and we had tea and coffee on the porch before setting out. As before, I walked out on my own, knowing that the faster paced Daris and Paula would catch up with me in an hour or so. The NBT continued as it had in the past: Mostly flat, forested, and with a lot of mosquitoes. On the entire 156K length of the NBT, there was only a single pass, and that was another day ahead. It was an easy route through the mountains, and its charm lay not in the alpine, but in the feel of the place, the wildness. Occasionally open view points would appear in the forest, revealing mountains in the distance, but these were not the prime attraction.

I thought back to the beginning of the trek from the border with muted delight. I was pleased at how the trip had worked out, but sad that it was coming to an end at Robson, only a few days in the future. I was glad to have the company of Daris and Paula for the last run, and yet I could not help but feel that the NBT was something to be experienced alone, like the desert. I liked the laughter and constant smiles from the ladies, as well as the stories of their interesting lives, but needed some space to myself during the day, and the morning seemed the best time. I thought about how many times I had heard "Some Day" this summer. Almost constantly on the Appalachian trail people told me how they would like to come out and hike Some Day. Some Day they would like to leave their settled life behind and migrate on foot for five months. Some Day they would like to experience the freedom that comes by living with only what one can carry on their back. Some Day they would change their lives so that they could spend their remaining years in happiness, rather than routine. But, for them, it was always Some Day, and never Today. In a month or so, it would be Some Day for me as well. In a month I would put on clothes made for an office, rather than a trail, and lecture students on some point of mathematics. I, too, would have a routine, a schedule, and would have to think in terms of Some Day. I didn't know how to make everyday Today, rather than simply passing time until the breaks in the school year gave me the time and space to live deliberately, as Thoreau once said. I was thankful for what I had, but I wanted more.

I met up with Daris and Paula at Nellie Lake, a pretty lake with a hulking mountain towering over it. We talked about where we might spend the night, and the Hoodoo warden cabin seemed like a reasonable choice, only 35 K from the Welbourne warden cabin. At least it would have a porch to shelter us from the rain and it was unlikely that any wardens, or other hikers, would be in the area. An hour from Nellie Lake we crossed the Blue river on a fun suspension bridge, swaying and moving with each step. Daris even simulated a fall from it, dangling herself over the edge before becoming upright again.

Everything was fun and happiness with the two of them. Such a good, positive mood is infectious, and I found myself smiling more than I usually did, found myself talking more, enjoying the company more. Everything was more, it seemed, when they were around. Alone I could think. But with them, I could be happy for a while and not worry about the near future when button down Oxford shirts would be the rule once more and runs to the grocery store would be looked upon as a chore, rather than a joy.

We passed a large lake on the way to the Three Slides Warden cabin, which provided a nice view of the distant mountains that we were slowly threading our way through. Just as quickly the view ceased as we moved through the forest once more.

The forest gave way to marshy lowlands, with their resident bloodsuckers, though from the marsh we did get a look into the future as Snake Indian Pass seemed to be sitting just on the horizon. Or, perhaps it was some other pass for some other time and some other set of hikers.

The clouds were forming once again and it seemed that our run of good weather was about to give out. Our pace quickened as we pushed for the warden cabin and a bit of shelter from the cold rain that seemed ready to fall upon us. The Hoodoo Warden cabin was just off the trail, through a marsh, and was empty and locked up tight, a massive lock keeping its warm inside safe from hikers and their evil schemes. The porch provided enough coverage from the rain that came down the instant we made the cabin, but not enough for sleeping purposes. The view off to distant Upright Mountain, with its massive glaciers, was satisfying, particularly as we were not on the glacier in this foul weather.

The temperature dropped rapidly with the storm and I hurried to cook dinner for some additional warmth. With dinner done and the rain still coming down, we looked to the woodshed for better protection from the weather. I could have set up my tarp and the ladies their tent, but the woodshed was more convenient. Indeed, despite the lattice work walls, it was dry and just big enough for the three of us to sleep in. Cramped, and with several resident woodchucks who were rather put out by our presence, it was nonetheless comfortable, at least for one night. We stayed up for a while swatting at mosquitoes and shouting insults at the woodchucks, hoping for good weather tomorrow for our only pass of the NBT proper.

Before retiring for the night, I made a last trip to the river to grab some water and was astonished by how much it had risen during the rainstorm, which was continuing now, but at a more subdued pace. I actually had to be careful to grab some of the glacial melt, as the bank was now partially below water. I stayed up for an hour, thinking about the day and the coming end of the trek, listening to the quiet breathing of Daris and Paula, broken only by an occasional mutter as they swatted at a mosquito. The rain had tapered off completely by 10 and I fell slowly into sleep in the cramped quarters, perfectly happy and content. Here, in a wood shed, the three of us slept in a space normally big enough for one, dogged by mosquitoes, and with cold damp air all around us. An outside observer would have declared us miserable. An outside observer, however, would not understand, could not understand, why happiness might be possible in such surroundings. They could only see the physical setting and compare it to their own, comfortable life, their hot food and warm bed, their bug free house and woodchuckless room. All physical indicators would point to misery. Everything else, those indicators that could not be seen with the eyes or felt with the skin or measured or weighed or formulated, pointed to contentment in the wood shed.

The ladies vacated the wood shed around 11 pm last night to set up their tent for more protection from the mosquitoes, giving me ample space to sleep comfortably. The weather looked questionable and my motivation to hike was non-existent. Only the lure of Snake Indian Pass got me going up the trail. Even though I knew the trail would be easy to walk, I also knew that I was in for a hard day. Hiking without motivation always is. The trail began to climb gently toward the pass which, following the pattern of all the passes in the northern Rockies, was broad and open. Indian Paintbrush dotted the landscape on the upper reaches of the pass, providing a nice foil to the dark green scrub and the tall, grey-tan mountains.

Daris and Paula caught up to me at the pass itself and we had a sit to think about the rest of the day and to soak up this final pass before reaching Mount Robson. There were so few alpine areas on the NBT that it seemed a shame to leave it too rapidly, if for no other reason than soon we would be back into the marshy forest land with the bugs.

The clouds overhead did nothing for my motivation. Usually seeing that rain was coming was enough to quicken my pace, but today I seemed mired in lethargy. I wanted to get to the end of the trail but, as with last summer on the PCT, did not want to see my summer come to an end. Fortunately, I had a couple of weeks on my hands before I had to move into my new place in Lakewood (that I had not found yet) and had to return to sedentary life once more. I had time to decompress, a luxury that I didn't have after finishing the PCT. Still, the prospect of rejoining civil society was not a comforting one. Eventually we had to leave the pass and the alpine and started down the other side of the long pass.

I took a final look back to the pass on the way down, tracing the thin creek back to where we had sat. the NBT was muddy and the trail was not in good shape. No attempt had been made to put in water bars or spars or any other device to prevent erosion of the trail. Fitting for the NBT, I thought. However, the trail areas around the warden cabins were always well maintained and groomed, and this seemed a bit provincial to me.

Staring down to the valley that held Byng campground I separated from the ladies for a little while. I did not want to contemplate, but rather I was hoping to muster some enthusiasm for the rest of the day. Oddly enough, I ran into two sets of hikers, but did nothing other than mutter hello to them on my way past. I wasn't particularly happy to see them and felt, quite selfishly, that they were invading our space. Of course, I was also invading theirs. The vastness of the land through which the NBT led should have been enough for many. But the feel of it was meant for only a few at a time. It was not a popular trail, and I hoped that it would never be. I hoped that the wardens would not clean up the trail. I hoped that the masses would gravitate to the Skyline and Jonas Pass areas, where the scenery was grand and the access easy. The NBT was perfect as is.

After lunching with Daris and Paula at the marvelously maintained Byng Warden cabin I set off by myself again, lacking dramatically in the enthusiasm department. I was dour and sour and wanted the day to end, to be magically transported to the Smoky River and a fine campsite. I struggled into Twintree lake, one of the largest lakes that I had come across during the summer time. It is always easy to spot a manmade lake as they are far larger than anything one finds in nature (there are a few exceptions to this, of course). Twintree had the delightful white-blue sheen of many of the lakes in the Rockies, caused by the large amount of dissolved rock from nearby glaciers.

Daris and Paula came up with a smile and we joined together once again at the local warden cabin. There was a row boat chained to a tree. An excursion onto the lake would have been rather pleasant, but the wardens had decided that this was a treat only to be enjoyed by those with property authority and a key. We still had 15 K to go to make the Smoky River warden cabin, which would hopefully be open and shelter us from the rain that was too obviously coming. I was tired of being lethargic and, our break over, hopped up with a forced enthusiasm. I sped down the trail just ahead of Daris and Paula, following the outflow of Twintree lake downhill, to where the trail crossed the now raging creek via a slender log bridge.

Powering up the other side, I lost sight of Daris and Paula in my effort to get to the Smoky River. Harder and harder I pushed, sweat flowing freely over my face for the first time in days. The trail climbed steeply up and over a shoulder of Twintree mountain before dropping down into a valley on the other side, deep in the woods at all times. Almost two hours passed and I was beginning to tire. Not physically, but rather mentally. I was done. The rest would have to be death marching. I sat at small brook and waited for the ladies, hoping they might pep me up a little. But, when they arrived fifteen minutes later, they seemed equally spent. After sitting for a while, they took off in front of me, leaving me alone to shuffle along the trail. Although I caught up to Daris as she foraged amongst the dense huckleberry bushes lining the trail (giving me a handful of the sweet berries), I did not see the ladies again until reaching the Smoky River warden cabin. A Canadian flag was flying from the flag pole, a sure indicator that a warden was there and might let us stay inside tonight.

However, when I arrived I found Daris and Paula sitting in two handmade rocking chairs and the place locked up tight. Perhaps the warden was on patrol? The cabin was significantly larger than the others we had passed and seemed to be some sort of district headquarters for the rarely seen wardens. There was no question of moving on, or even of where I was going to sleep. We cooked dinner on the porch and enjoyed the views of the mountains in the distance (warden cabins always being placed somewhere pretty) before the ladies set up their tent and I went to the wood shed to sleep out of touch of the rain, which began to fall shortly after dinner. Although Snake Indian Pass was grand, the day seemed to have been wasted in lethargy: I had only wanted to get to the end of the day, rather than enjoying the progress of time throughout. I was tired and beat and had a great desire to be somewhere other than where I was. I wanted tomorrow to come and go and for me to be within striking distance of the parking lot at the base of Mount Robson. I hated it when I got this way and hoped that my foul mood would disappear with the morning. The weather came in and a thick, white fog enveloped us, accompanied by more rain. I hoped for the next next, a hope that had no basis in rational fact or scientific thinking. It was a hope based on the faith that my body would heal, my mind would adjust, and my spirit lift with the next day's sun. Hope was all I had, laying in the wood shed. And the giggling coming from the tent as Daris and Paula told jokes, happy as always.

It rained steadily, though never hard, throughout last night, but I was able to stay dry in the wood shed, despite the crosshatch walls. The last full day of the GDT would be a wet one, it looked, from the weather. A thick mist hung in the forest, with drizzle falling, and cold breeze blowing. Not the best of conditions, particularly for getting a good, close up view of Mount Robson from Robson pass, thirty kilometers distant. I sat and drank strong tea and tried to screw up my motivation for hiking. I would not, I resolved, hike in the same mindframe as I did yesterday. I would not lose my desire. I would not be bored. I would not be tired. I would be a dynamo on the final day. I rallied and at 7:30 I was off on the trail, just in front of Daris and Paula, moving well. Within minutes my feet were soaked through from the water on the trail and clinging to the vegetation on the trail. Within 10 minutes, my softshell pants were wet through as well. I powered along, enjoying the easy trail, trying to ignore the rain and hoping, against all hope, that the fog and mist might lift as I got closer to Robson Pass. The low mist gave the landscape a spooky visage and made everything feel somewhat fantastic.

Rain came and went, came and went, and my upper body soon joined my lower body in dampness, as the sweat began to build up inside my rain jacket. As long as I kept moving I could maintain body heat well, but knew that on any break I would chill down rapidly. As we crossed a fog covered flank, Daris pointed out two moose that were foraging down below in the valley, apparently unaware (or unconcerned) of our presence. With my little camera, taking a picture would be worthless. After two hours I took a brief break, not wanting to cool down too much, and wanting to keep my momentum going forward for as long as possible. The fog, predictably enough, was not lifting although it was not quite as thick as in the early morning. Pushing, pushing, I felt like racing up the valley toward Robson pass. There wasn't anyone to race other than myself, which made the competitive spirit more like self assessment. No views, just the spooky river that threaded its way up the valley toward the pass.

During a lull in the rain I sat down under a bush and had a few snacks. The valley had begun to get more rocky and less forested. I was heading for the alpine for the last time on the GDT, a finality that was both depressing and joyful. Daris and Paula found me under the tree snacking quickly and sat down for a more full lunch. I wanted the pass and set out thundering up the trail, still hoping for a miracle clearing by the time I reached Robson Pass. Needless to say, this didn't happen, but I did run into several backpackers heading in the opposite directions, each of which got a grunt rather than a greeting. As the land openned up below the pass, the local mountains came out, shrouded in mist, which occasionally thinned enough to get a peek at a peak, or a sighting of a glacier. I passed one campsite, then another, and knew I was getting close to the end. The rain came back for the last kilometer of the NBT and it was in something of a squall that I stood at the boundary between Jasper National Park and Mount Robson Provincial Park. The boundary of Alberta and British Columbia. The boundary of the Atlantic and Pacific watersheds. The Continental Divide. The Great Divide. Whatever it was, there was the standard marker along with a large board that had some information about Mount Robson. There was a ranger cabin nearby, along with some campgrounds. I could find someplace to get out of the rain, even if it was in a privy.

After a few false turns, I found the ranger cabin on the banks of a small stream, looking warm and comfortable and quite empty. Investigating, I found the back door to the cabin open, intentionally left so by the rangers so that hikers could get into the covered back porch of the cabin. From the back porch of the cabin, one could get out of the rain, yet the security of the cabin was still intact as the door from the porch to the main room was locked up tight. Very nice arrangement, I thought. This seemed to be a reoccuring theme: Pronvincial rangers were helpful and on the side of hikers, national wardens generally were not (at least in my limited experience).

While not exactly toasty, the backporch was out of the wind and rain and I could sit on something dry. I shed my rainjacket and laughed at the cloud of steam that escaped and poured through my hiking top. I sat and rested for a bit, before adding a note to the ranger's notebook register, at which point Daris and Paul strolled up, looking at me a little sheepishly. I assured them that the door was open and that I had not broken in. I fired up my stove for to make a hot lunch and we sat in the (now) cramped back porch thinking of our good fortune, even if visibility was generally limited to 10 meters. We heard foot steps arroaching and stuck our heads out to find three day hikers, up from a lower down camp. The rangers were out working with a trail crew from the Sierra club building a retaining wall. Apparently, it was a large outfit, with big cabin tents and a lot of food. All three of us had the same idea at once: A dry, warm place to spend the night. There was no chance that the Sierra Club would not offer to let us spend at least some time in doors, with plenty of hot coffee, and they might even let us sleep in the cabin tent.

.

The day hikers left and I wolfed down my ramen noodles (fancy Korean ones that I had scored in Jasper), while the ladies had only a half dinner, saving the rest for later. I wanted the warmth now and forgot about the future for the moment. Remarkably, by the time we left the cabin the mist had lifted significantly and we were treated to local views of the valley and of Berg lake. The area reminded me alot of the high Khumbu, in Nepal: Lots of barren rock, little vegetation, glaciers everywhere. Indeed, a massively fractured glacier came spilling down off a mountain (presumably Robson), hidden in the mist, right into the lake. We hardly needed a trail at this point, given the breadth of the valley, but the manicured bridges over the streams were appreciated.

The trail ran around a beautiful lake on the pass and eventually ran by a large, plush cabin. Almost like a resort in the mountains, it was incongruous with its surroundings. It was certainly very popular, but I wished it wasn't around. Sort of like going to the opera and finding that Brittany Spears was performing. A tame marmot sat on the front porch, looking fat and complacent, like every other marmot in existence. Some fat and complacent tourists stared at us, in the mist, from the window of the cabin as we took pictures of the chubby creatures. I reflected that in the US this place would have been under federal control and would almost certainly have been declared wilderness. The cabin would never have existed, or would have been burned down long ago and never rebuilt.

Leaving the cabin and the microforest that it sat in, the trail returned to the gravelly plane, passing some people who had no business being in the backcountry. If the cabin wasn't close by, they would have died for certain had someone not rescued them. Of course the cabin was there. Perhaps we were not in the backcountry anymore, I mused, despite being more than 20 K from the nearest road. Although I was now in a good mood, despite the rain and the mist, I only grunted at them as I passed. They were about at their physical limit and, I suppose, knowledge that the cabin was close would have cheered them up.

Rumbling along the valley, the mist and fog lifted slowly, but certainly, although there was enough to still obscure any views of Robson. There was still enough to make everything scary and spooky and magical. What a nice treat, I thought, as the three of us rumbled on toward hot coffee and my countrymen. I could see pictures of Mount Robson at home, but I could never re-create the feeling of walking through the Berg Lake area in the mist.

We began to encounter the Sierra Club's handy work: A big solid rock retaining wall along the flanks of a rocky mountain. I was a little unsure of the utility of such a thing, especially given the fact that so much trail work needed to be done on the Jasper side of things, but it was volunteer labor. The Americans would have viewed this as a working vacation, and who wants to vacation on the comparatively dull NBT? Why not on the spectacular Berg Lake trail? Send the wardens to the NBT.

A man in a green jacket and no pack came hiking toward us and I stopped to greet and thank him. He had to be a ranger, and I had really appreciated his leaving the back porch open. We stopped and talked for a few minutes in the drizzle. He seemed to think that our reception by the Sierra Club might be a chilly one. "They're pretty tired and grumpy down there," he mentioned. No doubt, but when they heard that we had walked here from the States, they would warm up, I thought. I thanked the ranger for the fourth time and he sent off after telling us that it might be best to camp down at Kinney Lake, which was more or less empty, rather than at the upcoming camps, which were fairly full. Rumbling down the trail, I could smell the coffee, strong and thick, from a kilometer away and started bloodhounding along. A few twists and turns by the trail and a run into the woods found us in the mist and cold and wet standing out front of a large cabin tent, from which the coffee scent was wafting. I knelt at the entrance, not moving inside unless I was invited, stuck my head in, and said hello.

The three of us left fifteen minutes later, without any coffee, without even being invited into the spacious cabin tent, which was well heated by a wood burning stove. I had tried everything I knew, everything that should have at least gotten us an invitation to come in and warm up before moving on. I had made sure they knew that we had walked more than 1000 K from the States to get here and that tomorrow was our last day. I made sure that they knew I was an American as well, and that I lived in the same state as several of them. I made them laugh with simple jokes and smiled as much as I could. I made sure to complement and thank them for the hard work they had been doing. Twice. Three times. Volunteers, it seemed, did more trail work than the wardens and a well constructed trail was rather useful at times. At one point, the rain started coming down on us, as we were huddled outside the cabin tent. I could feel the heat on my face and, when one of the club members waved a cup of coffee under my nose, I wondered if they might chase me if I stole the coffee pot from under their noses. Alas, nothing. With the rain coming down, one of the other volunteers chuckled and said we would have to hoof it if we didn't want to be caught in the rain. They mentioned that they had built a new privy around the corner and told us to go look at it. And so we left, with out drying out and without coffee, and certainly without a warm, dry place to sleep during our last night on the trail.

We found their new privy, right next to the old one, which seemed to be in fine shape as privies go. Originally the three of us were going to huddle inside the old one to get out of the rain, but the place smelled and the rain had changed to drizzle. So, we sat under a pine tree, wet, damp, and with our defeat in recent memory. Daris took a picture of us, to commemorate our happy day. We pondered borrowing (stealing) one of the work crew's wheelbarrows and taking turns riding down the trail in comfort. In the end, however, the juvenileness of such an action seemed rather pathetic. The rain picked up and dropped off as began the long descent down to the river valley below, the valley of a thousand falls.

We couldn't be stopped. The trail was stunningly beautiful, but there were few places we could get out of the mist and cold to appreciate a break. At least while walking we could stay warm. Oddly enough, the temperature began to drop as we lost elevation. Waterfalls seemed to coming down from every possible notch in the valley walls. Some were small trickles, others massive things.

We passed a few hikers who looked like they should have stayed in camp, but mostly we had the place to ourselves. The bad weather was keeping most people in their tents rather than in the outdoors that they had come to experience. I would rather have been in the warm cabin tent drinking coffee, but if I couldn't be, the trail was the next best place.

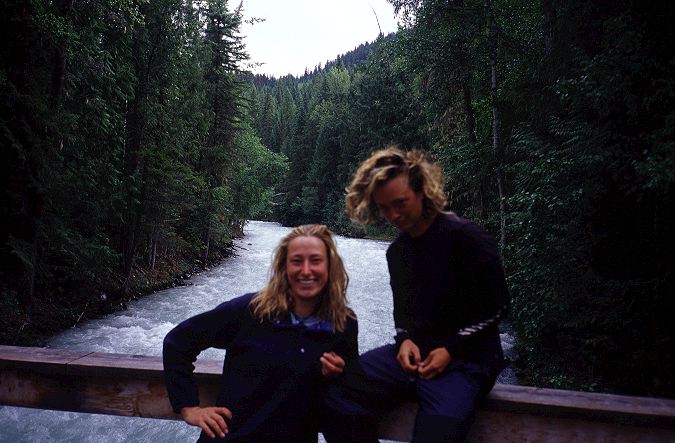

We had finally reached a pleasant looking campground on a river, complete with a covered picnic area. Unfortunately, as the ranger had told us, it was packed to capacity. Everyone was in the picnic area eating and chatting, and despite there being six big tables, there was no place to sit. The three of us huddled by the edge for a a smoke, under the watchful, wary eyes of the pavillion dwellers, to contemplate what to do. I happened to look up to the message board near us, and spotted that Kinney Lake, the ranger's recommended place, also had a covered picnic area! Only a few kilometers away. We shouldered our packs and set off, leaving the others, it seemed, somewhat relieved, and crossed the raging river on another fun suspension bridge. Motoring now, despite the rain letting up, we finished the last of the elevation loss and dropped down to a really nice, illegal campsite. It was right on the trail, but sheltered and well drained, and it was unlikely that any one would come by tonight or tomorrow before we left. It had even stopped raining. Although the ladies wanted to stop here, I managed to talk them into continuing on to the picnic shelter at Kinney Lake instead.

Thirty minutes later we rolled into Kinney Lake and almost instantly the heavens opened up. No longer a drizzle or light rain. Monsoonish rains and wind slammed into the area and the three of us were collectively thankful for moving on from the pretty campsite. There were a few families under the pavillion, but there was plenty of space for us as well. Daris and Paula had been clever enough to save half their dinner for tonight. I had only cold (even if filling) food to munch on. The temperature continued to drop, and for the first time on the GDT I was forced to put on all my clothes to stay warm. Even then my body heat was precariously close to being cold, something I didn't like to be. Still, we were all in good spirits, despite having hiked 47 kilometers today. We were about seven kilometers from the end of the trail, a distance we could cover in about 75 minutes, had it not been pouring down rain. One last night on the trail, then a bit of luxury with the ladies' parents.

A few soaked hikers rolled in as the others were trundling off to the security of their tents. There was no question of where we were sleeping, however. The three of us put our sleeping pads and bags down on the floor of the pavilion in tight formation and chatted with the soaked hikers after they returned from putting up their tent and started to eat their dinner of pizza bagels. It seemed like an odd way to spend a final night on the trail, curled up under a man-made structure after so much wilderness over the past month. While we had shelter the last few nights, there was something about the finality of tonight that grated on me. I had more than a month before my new job in Washington began and little to do in-between now and then: Find my way back to Calgary, pick up some stuff in Utah, find a place to live in the Puget Sound area. Unlike last summer, I had some time to decompress from the summer and slowly adjust to the demands of civil society: Shower regularly, use toilets, wear clean clothes, keep a schedule. Only seven kilometers from the end. I was ready to finish, but was glad I didn't have to go home just yet.

There was no great rush in the morning, although all three of us wanted to get down the trail to the end of the line and Daris and Paula's parents. Several of the campers found us still in our bags when they came over to cook breakfast, which forced us from our sleeping bags and into the day. Daris and Paula had no food left, and I had only a single oatmeal bar, so we skipped breakfast and began the final trek down to the Robson river and the end of the trail for the summer. The lower elevation of the trail from Kinney lake to the river brought about a final environment for the trek: Rain forest, complete with the beastly Devil's Club, a thorny, spiny plant whose spurs could cause great pain to the unaware. We took a final break under a massive cedar, along the banks of the Robson, whose trunk was large enough for all three of us to lean against and talked about anything other than the trail. Food, shower, where the parents might be. After sitting for a half hour, we made the final 10 minute walk down to the bridge over the Robson, passing a few hikers on their way up to the alpine. No monument, no cheering crowds, just a parking lot packed with cars and some backpackers gearing up. Once they crossed the bridge, we let out a collective whoop and took the mandatory pictures.

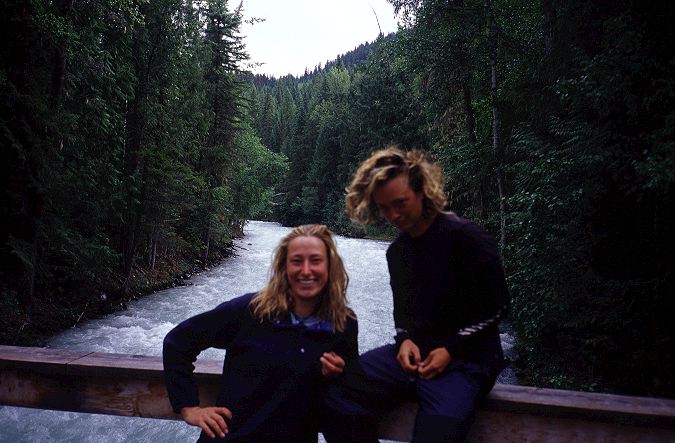

The grinning group shot, of course, had to be taken.

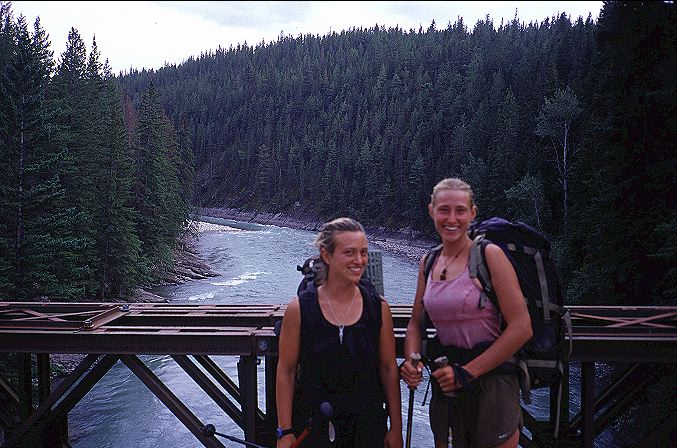

I needed a picture of Daris and Paula's wild, greasy hair, generated by several weeks between real showers with shampoo.

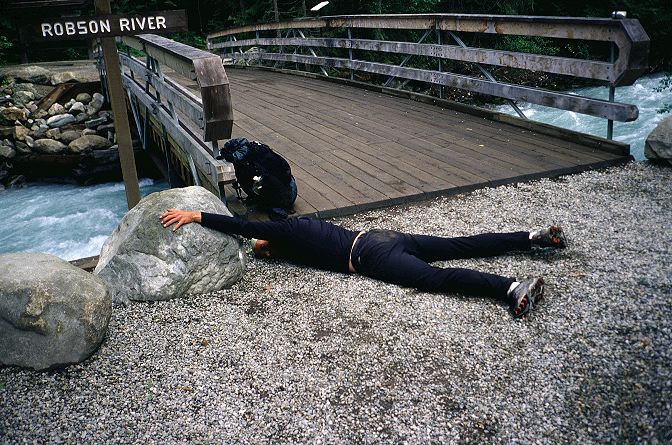

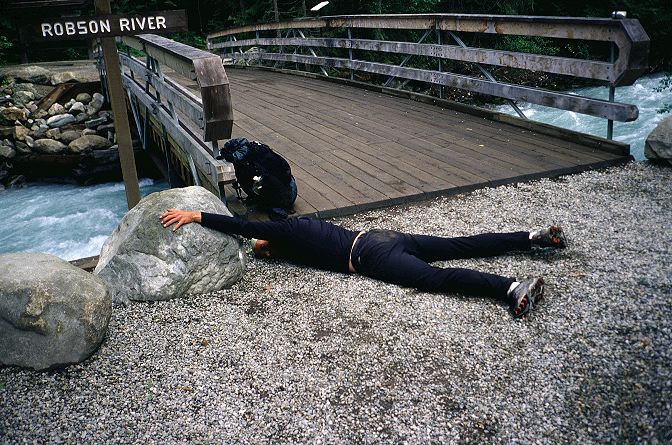

Of course, there had to be a photo of a hiker struggling to reach the end.

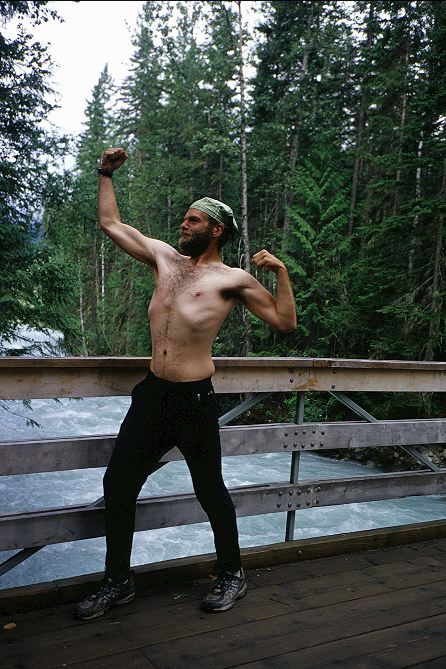

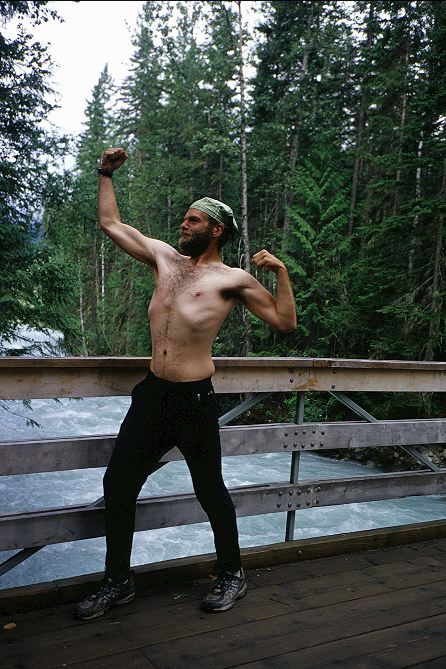

And I had to have a picture of me flexing after a summer of hiking, mostly so that in the winter I might remember that I was once in decent shape.

With the ending of the clicking of the cameras we had nothing more to do. No more trail to hike, no passes to surmount, no route finding difficulties. What we did have was a food problem. There were notes from Daris and Paula's parents, indicating that they were staying in a couple of cabins outside of the park. None of us had any desire to walk any more today. The garbage man was hauling away the trash from the trailhead parking lot and Daris talked him in to giving us a lift to the visitor's cente, where we could eat and called the parents. The garbage truck was really a pickup hauling a flat bed trailer, into which we scampered and arranged ourselves around various sharp instruments for trimming the bushes around the trailhead. The driver whisked us the four or five kilometers to the visitors center, at which we hopped out to unbelieving stares of the RVers milling about, seemingly lost as to what to do in one of the world's great mountain parks. Fortunately, for both us and them, they would have to do some walking to get to the real stuff.

We walked toward the cafe/gas station/tourist center and found Paula's parents just finishing breakfast. The standard familial scene ensued, although the collective hunger of three hikers after finishing a thousand kilometer trek was enough to get us inside quickly and into the food line. I ordered an omelet and hashbrowns and toast and coffee, and topped it off with a ridiculously sized raspberry scone and a huge blueberry muffin, both of which would have looked at home in the famous (among PCT hikers, that is) Stehekin bakery. In between mouthfuls of food I tried to introduce myself enough while not spitting food all over the place, or even chewing with my mouth open. I hadn't had to worry about that for a while, you see. I went back for another muffin before before the five of us rolled out of the restaurant and ran into one of Daris and Paula's friends, a mountain climber named Ian. Ian had recently climbed Mount Robson solo, on a non-standard route that sounded rather exciting. It was his second time to reach the summit and he seemed to spend most the season in the Canadian Rockies climbing various mountains, working on his climbing resume and hoping to tackle K2 sometime in the future. Ian was as close to a distance hiker as you can get while living out of van. He had the long beard, the tattered clothes, the wild yet serene look in his eyes. But rather than sleeping in wood sheds or under a tarp at night, he was in his van. I liked him immediately. Daris's parents miraculously showed up and the parking lot exploded in hoots and howls. At one point I was carrying Daris' mother around in my arms like a bride. I could see where she got her enthusiasm for life from.

The two sets of parents had rented cabins in a nearby "resort" (the resort consisted, more or less, only of the cabins) and we hopped in the cars and made a fast drive to showers, beer, and food. Within minutes of reaching the cabins, Daris' father had put a 750 ml bottle of a fine Chilliwack IPA in my hands as I ran though the introductions once again. Paula and then Daris and then myself got a crack at the shower and some clean clothes. I took another beer with me into the shower and came out to find some clothes that Paula's parents were bringing to an old aunt near Edmonton. I got to parade around in a bright yellow woman's top, but declined to put on the pants, prefering my now scrubbed hiking pants. If only their were bringing her a skirt, I thought. Day faded along, together with many beers and food and music. Even the mountain came out from behind its mantle of clouds, showing off Ian's route and all that we had missed the previous day. Time moved on, with or without me, and I felt a little sad even amongst all the celebrations and happiness around me. Daris and Paula were barely recognizable in jeans and cotton shirts, their greasy hair now clean and fragrant. I thought for a moment about buying supplies and simply walking back to Jasper. But only for a moment. My time was done, the summer trek was completed and I was once again relegated to the status of a tourist, or a touron, depending on my mood and slothfulness.

After a barbeque, people trundled off to bed, but Daris and I stayed up on the porch for a while, talking over one final can of Canadian. The stars, for once, were out and we were up last enough to see them, one of the only times during the entire summer that I had experienced this. Last summer was different. No necessarily better, but different. I had finished last summer and found myself changed. I was now unsure if it was the PCT that had changed me, ruined me in the words of some, or if it was only the event that had opened my eyes to the change that had been brewing for years. It was not like this now. I was fully aware of the change and felt in my element. This was the real world. There, sitting on the porch with a can of terrible Canadian in my hands, talking with Daris under the stars seemed to me to be the real world. Back in civil society, that was the fake or pretend world, where people pretended to be interested in you, or care about you, or pretended to be someone that they are not. Where I pretend to be someone that I am not. Where the truly meaningless becomes a matter of grand importance because some structure declares it to be. Where that which does not matter takes over from that which does. A place where hate and celebrity magazines and political causes and advertising and bigotry and lying and traffic and hiding oneself are the norm, rather than open freedom of a life lived with few possessions. That was what I found facing me in the near future, sitting on the porch with Daris. There was nothing to be done about it, so we went to sleep instead of trying to fight against something that we could never defeat, that we could only endure until the next summer.