Rocinante Stumbles, Pancho Triumphs

Rocinante Stumbles, Pancho Triumphs

December 16, 2008

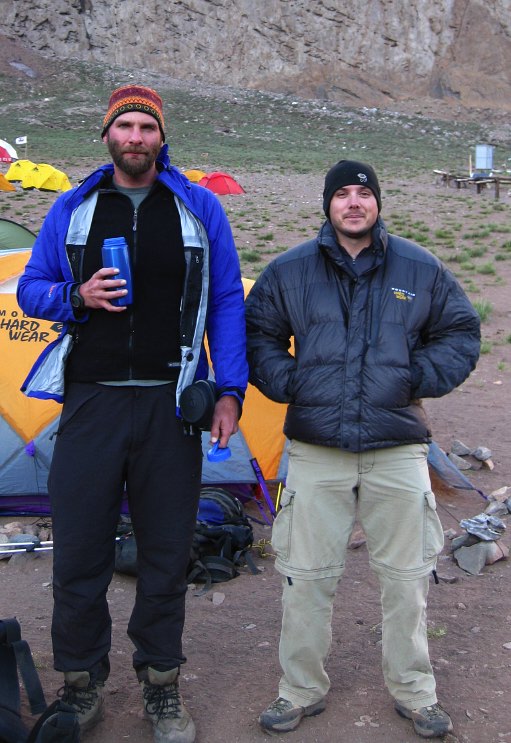

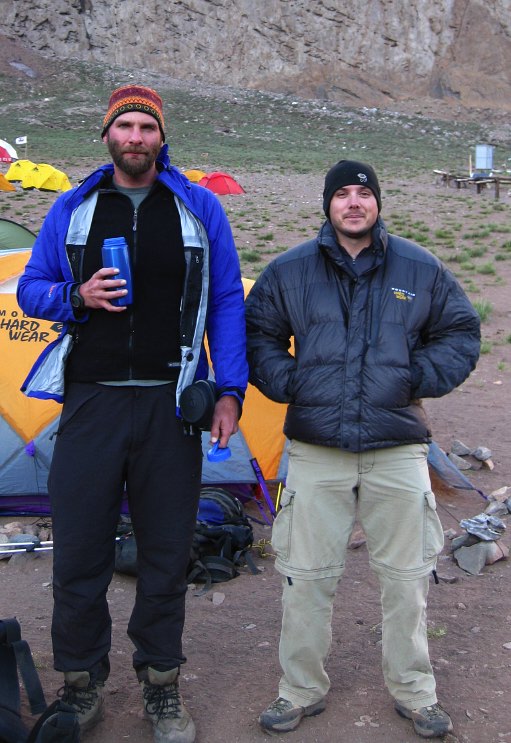

Today was the day, the day we actually started up the mountain and stopped talking about it. Even if it was going to be an easy day, we'd at least be on our way and out of the front country. We met Hebert after a terrible breakfast consisting of a single croissant and a cup of strong, instant coffee. Hebert has climbed the seven summits without oxygen and is characteristically humble. People who do big things seem to always have a sense of humbleness that distinguishes them from people who do fake big things, like Steve Jobs or Barry Bonds. Hebert picked up the three of us and Hebert and drove us up to the trailhead, where there was a ranger station and a helicopter. It was the perfect morning, with nothing but blue skies and the pale air of 9000 feet.

After registering with the rangers and picking up a bag for garbage we took the obligatory photos and started up the trail to the mountain. Although the lowlands were scrub desert, up here in the mountains there was enough of spring left that the land was coated in green. Even if the plants didn't grow very high, they were there and all of us were conscious that things would not last for very long. We would soon climb beyond greenery and enter the rocky, icy, barren alpine.

Our pace was slower by a factor of three than when moving back at home. Part of this was the altitude, but also was due to not wanting to exert ourselves. On an overnight climb of Mount Rainier you can push yourself knowing that you'll soon come down and be out of the thin air. We didn't have that luxury. Well, it was really more of a luxury to have two weeks on the mountain, but you know what I mean. Soaring all around us were craggy, 20000 foot mountains that probably saw only a few ascents every other year.

The stunning scenery continued up the mountain as we gained elevation. Our slow pace, set at a rate that kept breathing and heart rate close to resting, meant that we could linger and look at anything that took our fancy. This was the springtime for the Andes and the feeling of newness was palpable. We were in front of the main climbing season and in a few weeks the serenity of the approach would probably be replaced by the congestion of a freeway.

After two hours we approached and crossed a suspension bridge over the muddy river we had been following up from Puente del Inca. Fortunately we had found sources of water that were cleaner than this! Besides non-exertion, one of the best ways to stave off altitude related problems is to drink a lot of water. As you ascend your blood begins to acidify as your breathing changes. Your kidneys then have to work harder than normal to clean out your blood, which means you need more water than normal. Drinking the chocolate milk that flowed by would have been unpleasant.

On the other side of the bridge we left the jeep track we had been following for a trail up the valley and into the heart of the mountains. All the time Aconcagua sat in front of us, providing a view we'd have almost constantly for the next three days.

An hour or two past the bridge we were caught by two Swiss Germans on their way up to Confluenzia camp, where we were heading, for a day hike. Without packs they were able to manage the hike a bit better than we were, but I also suspect they might have been in better shape! We had crossed a few snow banks and the valley was now quite tight on us. However, as we topped out on one last rise we came to a plateau where the land spread out in a large, open plain.

This plain was where the new Confluenzia camp sat and was our destination today and our home for the next two. Because of the number of people that come into the area and the limited resources of the government for something as silly as mountain climbing, you need to contract with a company to use the toilet and camp. The main guiding services all had patches of ground claimed and had put up huts and tents for those not willing to camp or cook for themselves. There was a ranger station and a nurse-tent here as well as a helipad.

After checking in at the ranger station we made our way over to the patch of ground claimed by Rudy Para and Los Puquois. "Ground" might be too kind. It was more like a patch of raked dirt: The green-ness of down below was mostly gone. The tent was new to us, having been purchased used from a local mountain guide in Tacoma. We had re-sealed the seams and attached many tie out loops to it. For three people it was cozy, but certainly livable.

We had little else to do with the day now that we were here. Try not to get sun burned. Drink lots of water. Rest. I napped. Wayne flitted about. Kevin went for a walk. In the late afternoon we met up with the Swedes we had seen on the bus. They had come up to camp yesterday and were stuck here for another night as two of their party of four were sick with altitude. The nurse station provided a bit of common ground for people to meet at and it wasn't long before there was a solid clutch of climbers waiting to get checked out.

The nurse took our pulse, blood pressure, and oxygen saturation level and gave each of us the same speech about staying another night in Confluenzia to acclimate. It didn't matter what our numbers were, they were never good enough to move on. Many climbers were choosing to ignore him. We had the time and decided to spend tomorrow on a day hike to 13,500 feet to look at the immense south face of Aconcagua.

The heat of the valley vanished in an instant when the sun went down shortly after dinner. Whereas we had been sweating in the sun, we were now shivering in the shade. It was, after all, 11,500 feet above the sea in the spring. All my down clothing was now up at basecamp, but I had enough other layers to keep moderately warm as the nightly volleyball game amongst the guides, rangers, and workers started up. I watched a few minutes and then dove inside the tent for the warmth of my sleeping bag and a few pages of Solzhenitsyn. Outside I could hear the hoots of the game and had a hard time remembering that people do acclimate to altitude given enough time. I was getting winded just walking to fetch water, but the permanent residents of the camp were racing about as if there was nothing to it.

The early evening progressed on and the volleyball game slowly came to an end as daylight faded. The mountains were big here and the sun went behind them much earlier than the light ended. I went out to use the bathroom and was greeted by the local overlord mountain lit up nicely with the soft last light of the day. The colors of it were amazing, as were the striations caused by, well, whatever. I didn't have the training or the knowledge to say how the mountain was formed or what caused it to look the way it did. Part of me cared about this and wanted to be able to say what had happened that made it look that way. But most of me didn't care. It was enough to be here and see it.

It was frigidly cold in the morning, but once the sun came over the ridges is warmed quickly. The three of us and Peter were heading up a side valley to a place called Plaza Francia, which is the base camp for anyone bold enough to try to climb the south face. It didn't take long to get ready, but there were chores to be done, notably filtering water. The water source for Confluenzia had a very heavy mineral content and even with the use of the filter had started to wreak havoc on our insides.

With only light day packs the walked was comfortable and easy, though we took the same slow, plodding pace. The Swedish group left just before us, hustling as always, despite their two sick members who seemed determined to push on despite bad symptoms of altitude sickness. The two sick members, interestingly enough, were both medical doctors.

After dropping into a gorge we made a right turn and started up the valley leading toward the south face. Although it was still cool out, the day was rapidly warming under the heat of the sun. The thin air lets more UV radiation through and the danger of sunburn, or worse, gets greater the higher up you go. The closest tree was probably a hundred miles away and we would be in the sun the whole day.

We made slow progress up the valley and it became increasingly dry and barren and started to remind me of the floor of Death Valley, which I had traversed a few years ago. Except for the glaciated, 20000 foot mountains around use with frozen waterfalls. Death Valley has a lot of weird stuff, but it definitely doesn't have a glacier anywhere close by.

A group of hikers guided by Aymara, one of the larger companies, came past us in a rush. Rather some of them did. The guides apparently didn't care where their clients were and they were strung out across the valley. Given the pushiness of some of the clients I wasn't too surprised that the guides didn't want to be around them. Then again, the guides were borderline assholes and perhaps it was the clients who stayed away from the guides.

The Swedes had told us that the trip up to Francia was boring, but none of us found this to be the case, Kevin least of all. Since starting up the mountain he had stopped taking his thorazine and we finally had to resort to tying a rope to him to keep him from straying off.

The climb leveled off and we began making a slow, ascending plod of a broad valley hemmed in by steep mountains on the right and a rubble covered glaicer on the left. In the picture below you can see some of the Aymara assholes in the distance and the start of the south face of Aconcagua. From where we are it is nearly 10,000 feet to the summit. The face is steep!

When we broke the 13,000 foot level the wind started to blow a bit and by the time we reached a lookout to Plaza Francia the wind was stout enough to require jackets for warmth. The huge south face was above us and provided for endless speculation. How in the world would someone climb it? There were a few lines, but they all looked like at some point you'd have to be very lucky not to die: There was always something hanging above you that might cut loose. Perhaps it was more of a winter climb.

The Aymara people were down below us out of the wind and we let Kevin off of his leash so that he could get out of the wind. Wayne went to keep an eye on him while Peter and I stayed on top. It was pleasant in the sun, despite the stiff wind, and the views were incredible. Just like a blend of the desert southwest with the North Cascades.

After having a bite to eat I fell asleep in the sun and dozed for fifteen minutes. A few other hikers had arrived, including two elderly men who clear did not do this sort of thing on a regular basis. They were stepping outside what they were used to and instead of looking at Aconcagua from the road, they walked in, spent the night, and had come up to get a better view. I was happy for them, especially as they were from Texas and everyone knows that the water in Texas makes people lazy. We chatted for a moment and then started back down to Confluenzia as we were all a bit short on water.

With all the hikers and climbers that pass through the area, the land has many ruts where people have walked before. This makes for some confusion if you are trying to follow a specific one. However, if you take the viewpoint that you are heading down hill to Confluenzia, then any will do. We got a bit separated and Kevin broke free of the rope when my head was turned looking for the others. Before I knew it he had scrambled to the top of a large boulder and began to dance in the wind. I shook my fist at him and called him many foul things, but like a cat in a tree he just wouldn't come down. It was only when Wayne and Peter showed up and we threatened to leave him up there that he came down.

Back at camp we rested and napped and explored around a bit (ok, so I just napped, the others were more active) before heading to the nurses tent to be told that even though our pulse, blood pressure, and oxygen saturation were the same as before, we were now ok to go higher. The volleyball game from the night before must have generated some ill will between the teams. The locals had on their game faces and even took the step of watering down the dirt court to keep the dust down. They were serious.

The sun went behind the ridgeline and I got into my sleeping bag quickly for some warmth. Besides, it was easier to read Solzhentisyn while laying down than while sitting on a rock. Tomorrow we had a long day planned, with a solid hike up to 14,500 feet to basecamp, with most of the elevation happening toward the end of the day when we would be the most tired. Everyone was feeling strong and healthy and this was a good sign for us. And reading Cancer Ward was definitely helping: I was fortunate to be out here doing this thing, rather than cooped up in a hospital waiting to have my leg cut off.

It was colder overnight than it had been and we awoke at 6 am to a chilly morning. The sun wouldn't come up over the ridge for several hours, which was precisely the reason we were up so early: The climb to Plaza des Mulas would be brutally hot unless we got a jump on the day.

The route from Confluenzia to Plaza des Mulas is not a complicated one: Cross river and continue up the valley until you can't go any farther. We were moving at 7:30 am with plenty of cool air and quickly dropped to the river, crossed it on a bridge, and climbed into the sun on the other side. A stop was needed to put sunscreen on and change out a few bits of clothes now that the heat was here.

The valley on the other side was one of the more beautiful places I'd been to. Although there were a few bits of green scattered here and there, the dominant colors were earth tones: Gold, crimson, ochre, mauve, beige. The mountains forming the valley rose to craggy, icy peaks with a glacier to be seen here and there, the blue ice of the alpine contrasting pleasantly with the searing valley floor.

The route took us along the banks of a river, though I left the others for the far side of the valley to get pictures with a better perspective, and for that I needed distance. Pictures of landscapes without humans in them tend to have a certain lack of depth. The scale just isn't quite right. But with humans in thee picture it is easy to tell how large or small certain aspects of the land are. And we were tiny, tiny objects in this land.

My route ended up being a bit more efficient than the one that others took and I found myself at a large rock with some time on my hands before they arrived. I came down to South America with the intention to climb a mountain, but i realized sitting on the rock that, once again, the time spent trying to achieve the goal would end up being more precious, more memorable, than the attainment of the goal itself. Anything worthwhile is like this.

Together again, we continued up the valley, which began to narrow perceptibly, with the mountains closing in, squeezing us toward the river, which itself was starting to shrink. We were heading for a prominent mountain in the distance which, I guessed, would mark a change in the course of the valley. Navigation was simple: Walk to the mountain, make a right turn when you can.

The green had gone away completely and there was less life on the valley floor than in Death Valley, the place in the United States that seemed closest in spirit to this place. Except for the 23,000 foot mountain in the distance and the glaciers above us. We were making good progress up the valley, taking breaks as we needed them, but mostly moving forward and slightly upward.

We made our right turn and the river began to pin us to the side of the valley, requiring a bit of rock hopping and side hilling to avoid a dunking in the glacial stream. It wasn't difficult, but it required a bit more effort than the slow plod up valley that we had been used to.

After a solid rest a place with a sign calling it "Ibanez" we began the slow trudge toward Plaza des Mulas. We were now well past 12,000 feet and the thin air was beginning to tell on all us. Heart rate up, a pulse strong enough to be heard, and a general lack of energy. All normal, but not pleasant even if expected. In the distance I spied a large, prominent black peak rising from the middle of an expansive snow field. That had to mark the end of the valley.

The route wound in and out of drainages and unfortunately insisted on going up and down, rather than simply climbing and plateau-ing. The reason for this was the river: It passed through something like a gorge and the trail had to climb above it, only to descend back down a bit later on.

Ever so slowly we broke the 13,000 foot mark. Without an altimeter it would have been hard to tell that we were going up at times as the climbing, once past the river, was gentle and there was little to break up the monotonous stone-color of the rubble we were crossing. Plaza des Mulas was in sight, but it was still a ridge or two away.

Plaza des Mulas used to be located further down, near where we were, until an avalanche erased it. A ruined building was left, but not much else. As a result, we had to continue up to the top of a ridge and then down the other side, and then up some more, to get to camp. We were all feeling tired and began to separate as we each focused in on our own tiredness.

At last we walked into camp, which resembled a small city more than it did a climbers camp. There were satellite dishes, quonset huts, showers, dining halls, and signs advertising wine, beer, and chow. Tents were definitely in the minority at basecamp, but I suspected that would change as the climbing season got into full swing.

After checking in with the rangers we retrieved our duffles from the Los Puquois tent and found a spot to pitch three tents. Peter had his own and the three of us had a spare in case one of us got sick above base camp and had to descend. We would leave Wayne's tent down here when we made the move to Nido des Condores at 18,000 feet.

Conveniently, there was a kitchen with rock walls all set up for us already and we didn't lose much time in brewing up hot water for dinner, soup, and tea: Once the sun went down, it got very cold! While I don't especially like freeze dried meals, I had to admit that the Turkey Tetrazini that Wayne loved so much was actually quite tasty, especially as I was starving and craved anything that didn't have loads of sugar in it. 25 ounces of tea rounded off dinner.

I crawled into my sleeping bag with a heart ache and the feeling of my pulse inside my skull, but dinner did me good and after I began to digest the food I started to feel better. By the time I turned off my headlamp and closed my eyes, I felt positively alright. Of course, I was laying down and had just finished reading a chapter of Solzhenitsyn, but still I hoped it might carry over until tomorrow.

With nothing to do today but rest, we took the luxury of sleeping in and waiting for the sun to warm Plaza des Mulas before leaving the tent. It was a bright and sunny morning, something that was rare at this time of the year back home. I drank a liter of green tea and ate breakfast in the sunshine as basecamp slowly came to life.

Around 11 the four of us wandered over to the hotel, mostly to get some exercise but also for an opportunity to use their satellite internet connection to send out a few emails and check the upcoming weather for the mountain. The park rangers had an extensive operation running here, but they didn't do something as simple as post a weather forecast. The refugio, or hotel, was a fifteen minute walk away, but to get there we had to negotiate our first neves penitentes field.

Penitentes are towers of snow that are formed via a strange melting process and are common in the Andes, but more or less unknown in North America. The closest we have are sun cups, but the penitentes can be man-sized, where as suncups are usually no worse than calf deep. Even with a night at 14,300 feet, the air was thin enough and our bodies not acclimated enough that we actually took breathers on the climb to the refugio.

The refugio was a large, pleasant looking building that seemed to be a bit out of place in the area. I suppose this in just the clash of outdoor ethic between Americans and the rest of the world, but it seemed a lot like putting a Starbucks in a church. Sure, it was convenient and people would use it, but was it really and truly appropriate? America is one of the few (only) countries that keep things like hotels out of the backcountry. To Peter, a German, this was the most natural thing in the world. Even Canadians have huts in the backcountry so that skiers don't have to pitch a tent in the snow.

The high season hadn't started yet and so far there were only a few guests at the refugio, which was dark and cold inside. There were few places for the light to shine in and warm the building, which meant that it was more comfortable to sit outside in the warm sun than inside. A banner of Che Guevara inside the refugio seemed particularly funny, but I didn't try to explain the humor in it to the locals.

After checking email and having a bite to eat, we wandered back to Plaza des Mulas and our tents. There just wasn't much else to do. My plan involved a 2 hour nap, a trip to the nurses, a short bit of gear organizing for tomorrow's carry up to Nido des Condores at nearly 18,000 feet.

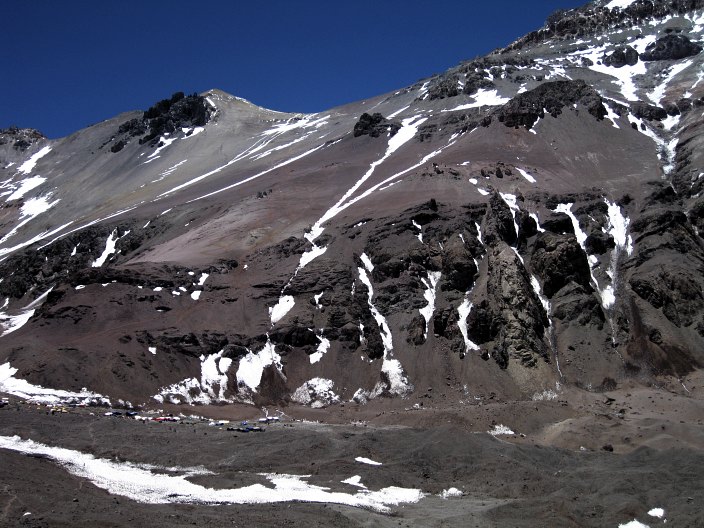

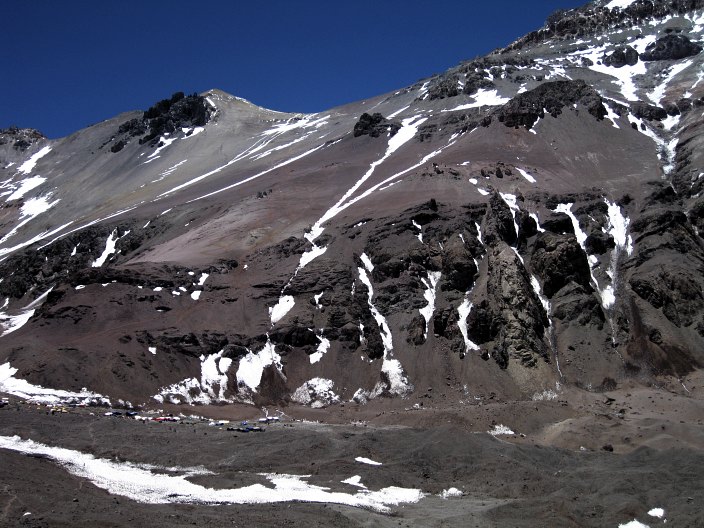

On our way back we got a very good look at the route we would be taking tomorrow. In the below photo you can see basecamp in the lower left. Above and to the left of camp you can see a faint trail leading above some cliffs and eventually through a rockband. Camp Canada (or Camp 1) is located behind the prominent rocks in the middle of the photo, upper 80%. Follow the long snow streak in the middle all the way up. To its left is Camp Canada. That is about 1200 feet above basecamp. Nido des Condores, where we were heading tomorrow, is out of sight, but located in the gap above and to the left of Canada. Although it looks close, it is almost 4000 feet above basecamp.

We straggled back to basecamp separately and I headed inside the sun-warmed tent for a nap. It was nice to be able to take a day where all I had to do was to rest. Zero days on a long distance hike are perhaps more delicious, but a rest day in camp was plenty slothful for me.

The evening brought us to the nurse's station, where we had our numbers read by a cantankerous nurse and a pretty, pleasant one. My blood pressure was actually going down (good) but my oxygen saturation level was down as well to 81%, which is on the low side of good and a full 10 percentage points lower than at Confluenzia. Kevin's saturation was the same, something that seemed to amaze the nurses. We were cleared to go higher though I got a rebuke from the pretty nurse for not putting enough sun block on my hands, which were slightly burned.

The rest of the evening was spent eating and getting gear sorted for the carry to Nido des Condores. We would drop the load up there, store it in Peter's extra tent, and then come back down to sleep at a lower elevation. My pack weighed in the neighborhood of 45 pounds, which seemed like a lot. But it meant I would have a very light pack when we actually moved to Nido in a few days time. As with the day before, once the sun went down it got very cold very quickly and I was soon inside my down cocoon reading Solzhenitsyn. Tomorrow was going to be a big test for our group. If we made it to Nido in a reasonable amount of time and were not burned by it, our chances of making the summit would be good. It didn't take much effort to fall asleep, even with the do-nothing day.

It was bitterly cold on the side of the mountain as we climbed out of Plaza des Mulas and toward Conway Rocks, the first major marker of the carry to Nido des Condores. The four of us were moving at a snail's pace to try to ward off the effects of the thin air as well as to compensate for the heavy loads on our backs. The wind howled as we made our way up through the rock band that was acting as a funnel and toward the sunlight.

We were carrying a large portion of the supplies we would need for the upper portion of the mountain to Nido des Condores, which means Condor's Nest. There was a camp in between, Camp Canada, but we thought that it made more sense to head directly to 18,000 feet from 14,500 feet, and then come back down for a night at 14,500. This way we would be able to stress our bodies with the higher altitude, but recover overnight at the lower camp.

At Conway Rocks the sun came out and warmed us, but the wind was still blowing hard and exposed skin got cold in a great hurry. We had been told by some Canadians to bypass the track to Camp Canada and instead take a direct route up to Nido des Condores. Although they meant well, this turned out to be the absolutely the wrong direction to take, for the footing wasn't good and the way was steep.

As we moved higher on the scree field we began to slow, except for Kevin, that is, who seemed to be immune to the thinner air. We also began to get stretched out as we each followed our own pace. Although it was good to stay close, it was better to not get overly tired or overly cold. Besides, the entire flank of the mountain was barren and we could keep and eye on each other even if we were not within talking range.

Kevin was far our in front when we started to pass through the 16,500 foot level. I was under the impression (from our guidebook!) that Nido des Condores was around 17,200 feet in elevation and thus thought that we were getting close to the camp. But nothing was in sight. The discouragement added weight to the thumping headache and extreme shortness of breath that set in as I rose above 17,000 feet.

Wayne was somewhere down below. Peter and I were close together, but I found myself stopping frequently to gasp for air. Even when I wasn't stopped I frequently took multiple short breaths as I was moving, as if I could gain more oxygen that way. And the headache continued to thump, keeping time with my pulse. I watched my altimeter go up and up and up before I finally spotted the camp in a notch on the far side of a gently sloping plain.

I was weary when I finally stumbled into Nido des Condores and found Kevin trying to stay warm. He had reached camp about 45 minutes in front of me, with Peter about 10 minutes back. Wayne was somewhere down below. The wind was blowing at a sustained 30-40 miles per hour, which meant that getting Peter's tent set up was a challenge. It wasn't helped by a lack of stakes and a lack of tie out loops. I found myself chilling quickly as I held the tent down in the wind while the others worked. The chill increased to a shiver, and the shiver to a full-body twitch. My muscles were rapidly contracting in an attempt to warm my body. It was the start of hypothermia. I had to get out of the wind, and the only place to do that was the tent. At least my body would keep the tent down while Peter and Kevin worked at getting it secure. I curled up inside on top of my sleeping pad and shivered. Slowly the St. Vitus dance I had been going through slowed. My headache didn't though. I heard Wayne's voice and a few minutes later I came out of the tent to begin the descent. I wanted to get down, and get down quickly.

The wind hadn't let up at all, but the tent was secure and we stashed our loads inside of it for additional weight. I began to shiver once again, but the movement helped keep away the worst of it. I was very happy to start the descent and moved off at a fast pace in an attempt to get down and out of the wind. Nido des Condores sits at a notch and it completely exposed to the mountain winds, which were ferocious this afternoon. However, as we dropped down to 17,000 feet I began to feel better, my head ache went away, and I was warm enough to stop and take a few photos.

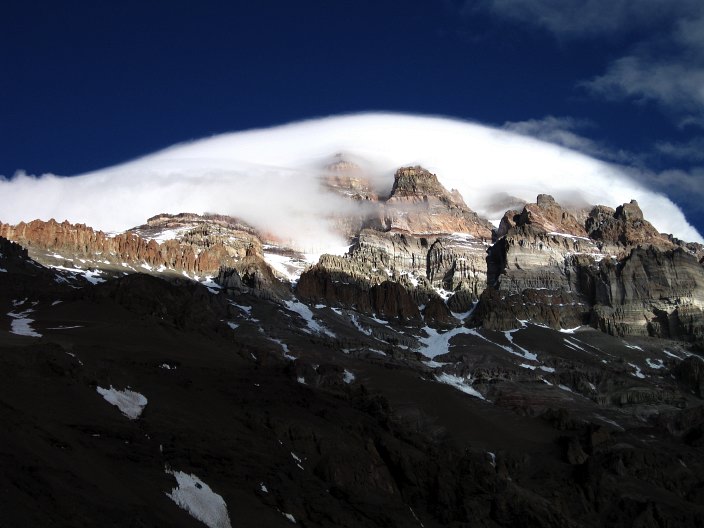

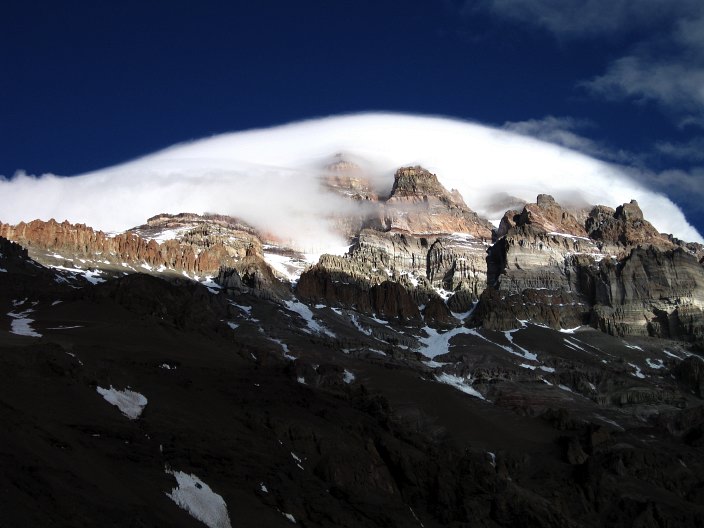

A storm was coming in and it would be good to get down to Plaza des Mulas sooner rather than later. We dropped down the scree quickly, surfing and plunge stepping as quickly as possible. I took a spill at one point and bent up one of my poles, though not so bad as to render it unusable. We took a rest as a group near Camp Canada in the sunshine and watched the storm come slowly over the mountains toward us. We still had a few hours, it looked, until it reached us and there was no more need to hurry. It had taken us a little over seven hours to reach Nido, but it would be less than 90 minutes to descend. Wayne hadn't gotten much of a rest at Nido and so decided to stay for a bit longer in the sun. The rest of us dropped down through Conway Rocks and arrived back at Plaza des Mulas tired and worn out. The upper mountain was engulfed in what is known in the area as a White Wind. We'd call it a lenticular.

We had been down for nearly an hour and a half when Wayne showed up. He had taken a nap in the sun and then dropped down slowly, but wasn't feeling especially well. Even after dinner and hot drinks he was definitely sick and took to his tent early. That seemed like a fine idea and after a few minutes inside of my sleeping bag my headache went away and I started to feel almost normal. My body was doing fine with the air at 14,500 feet and I hoped that after a rest tomorrow I'd be able to function a bit more at 18,000 feet than I had today. I didn't know why I had gotten so cold at Nido, but it bothered and worried me. It could have been a lack of calories or the thin air, but the others were not so affected by it as I was, and we had been wearing similar clothing. But for now all was forgotten as I settled into my warm bag and closed my eyes on a very tiring day.

Neither Kevin nor I had any intention of leaving the tent until the sun was shining on us, which made for a lazy morning indeed. I finally emerged around 9:30 and started water boiling for tea. We had decided to take a rest day at Plaza des Mulas before moving to Nido des Condores. Wayne was feeling under the weather and went to the nurse's station to get checked out. Unfortunately, he came back with bad news. The picture below has nothing to do with the bad news, but just shows Kevin filtering water with the gravity filter we brought along.

One of the nurses thought she heard fluid in his lungs, which is a sign of high altitude pulmonary edema, or HAPE. This is something that kills people and we didn't take the news well. The other nurse didn't hear it, but thought he had some sort of upper respiratory infection, which also wasn't good news. His oxygen saturation was dropping as his body devoted energy to fighting the infection and he was now out of the "good" range. He took some powerful antibiotics and retired to his tent to rest. The photo below has nothing to do with Wayne's illness, but does show Peter and his tent. Fabulous picture. The metal cans in the background are the toilets.

After a leisurely morning we went to the refugio again to get a weather forecast and eat some lunch. Again, more bad news. We had solid weather for the next four or five days and then a system was coming in, whose duration was unknown. It was right in the middle of when we thought we might be able to summit. If everything went perfectly and we all acclimated fine, there should be able to make it. But if we needed more time, and it looked like we did, then there were going to be problems. Wayne showed up and ate a steak sandwich, but was still under the weather and moving very slowly.

In the afternoon Peter and I went to the nurse to get checked out once more while Kevin spent the afternoon scrambling up a local peak called Bonnette. Our numbers were fine, but we were starting to talk about what to do if Wayne needed a few days of rest. Or worse. There didn't seem to be any good alternative. The weather meant that our window was probably now, but Wayne definitely couldn't go higher for a few days and even then solo climbing was not a good idea. It took three of us just to get one tent up. How could a single person do it? The picture below is of our kitchen and has nothing to do with our planning.

When Kevin got back in the early evening we talked and plotted and schemed and tried to make things work out. There just wasn't any good option. Our deliberations drug on and on. Finally Wayne and I had a short heart to heart talk that crushed the joy out of the climb. We were going to leave our friend behind and make a rapid push for the top. Wayne understood. He would make the same choice, but that didn't stop any of us from from feeling awful. I took a photo of myself afterward and even now looking at it makes me sad.

Peter, Kevin, and I decided to leave our tent down here and try to cram into Peter's up at camp. It wouldn't be pretty or comfortable, but it was a lot easier than hauling ours up. The sun went down and even the spectacular alpinglow on Aconcagua couldn't cheer me up. The fun of the climb was over for me. No longer was this about three friends climbing a mountain together. It was now about getting people on the summit.

It was bitterly cold when we said our goodbyes to Wayne and started up the hill toward Nido des Condores. Kevin was hauling a heavy load and that kept him within eye sight on the climb up, whereas Peter and I had lighter loads than before and could keep up. We were now familiar with the route and made good time to Conway Rocks, where the sun came out for the first time and we put on heavy doses of sunscreen.

Rather than take the direct route that we took last time, we decided to take the route that led to Camp Canada. This turned out to be much easier as the trail was very gentle and the footing much more solid.Although it was probably longer distance-wise, it took less time and far less energy than our route before. We reached Canada in good order and ran into two of the Swedes there. David and Joel told us that the other two, the ones who had been sick, were still stick when they got to basecamp and decided to go down. Canada looked like a reasonable place to camp, but I wasn't sure where they were getting their water from.

After a solid rest and some food we set out once for Nido, which we now knew was closer to 18,000 feet than the guidebook suggested. In the photo below Nido sit out of sight in the prominent gap. The route goes past rocks, which are near 17,000 feet, near the gap and then climbs up on an ascending traverse to Nido.

So far I had managed to stay warm and to keep my breathing and headache under control by carefully regulating my pace and the way in which I breathed. Deep, rhythmic, and soft breathing seemed to keep the headache in the background, whereas if my breathing became sharp and sudden the headache came to the fore.

Once past the 17,000 foot level the headache and rapid fire breathing came back. I staggered into camp with Kevin, just a bit before Peter, and dropped my gear at the tent, which was fortunately still standing. My head was pounding and all I could do was sit still and try not to cry. After stashing gear in the tent I took some Diamox and aspirin, neither of which helped. I had gone through two liters of water on the way up and as I rested Peter and Kevin melted some snow for more water. The snow was very dry and it took a long time to get anything out of it, which meant I had to wait for some time before being able to gulp down a liter of soup and some green tea before dinner.

My head kept thumping away and I was almost incapacitated by it. After dinner we all tried to jam inside Peter's supposedly three man tent, but found it was really a two person, despite what he thought. Finally Kevin got fed up of trying to position ourselves and took his sleeping pad and bag outside for a bivy at 18,000 feet. I was hurting too much to object or try to take his place, though Peter tried hard.

My headache continued to thump away and was joined by a new problem. As I closed my eyes and slowly started to fall asleep, I woke up gasping for air. Every time I neared sleep, my body forgot to breath. Over and over and over again. It wasn't until the early morning that I was finally able to doze off and the night was one of the worst I'd ever experienced.

After a night of repeated suffocation, I wasn't in much of a mood to do anything. I managed to get out of the tent and make some green tea. Kevin and Peter seemed to be feeling fine and were planning on a hike up to Camp Berlin, which was our next destination after a day of rest today. I should say the next destination for Kevin and Peter, for I had no intention of going higher tomorrow. I needed time to acclimate to the altitude and the storm that was due in two days meant that I didn't have the time. I was going down.

I managed to nap in the late morning and felt better, but still not up to speed. I was going to haul my gear down and what ever of Wayne's I could managed. I was still comatose when Peter and Kevin left for Camp Berlin. Around 1 pm a man from a local company showed up and told me in broken English that Senor Wayne had sent him as a porter for the gear, something that made me quite happy as it meant my load would be more reasonable on the way down.

After making friends with a German named Marcus who was up for an acclimitization hike, I packed my gear, got Wayne's to the porter, and set off for Plaza des Mulas. Once I dropped below 17,000 feet I felt almost normal and I realized that I really just needed another day or two at Nido in order to function above it. But timing isn't always perfect and I was happy to be descending rather than ascending. I reached Plaza des Mulas around 3:15.

Wayne was surprised to see me and I spent a little while explaining what had happened to me at Nido des Condores. He had visited the nurse's station several times and his oxygen saturation continued to drop, now into the dangerous range, as his body did battle with an upper respiratory infection. He was heading down tomorrow and would attempt to make it to Mendoza tomorrow night. I was glad to see him once again. After dinner I curled up in the now-empty tent and had a hard time remembering how bad I felt at Nido. Peter and Kevin were up there now and if everything went well, I would see them in three days. As it turned out, I saw them in two. But I'm getting ahead of myself!

Wayne came by the tent early in the morning to say good bye. We planned to meet at the same hostel in a few days time when Kevin and Peter got down from the upper mountain. I slept, deliciously, until 9 am. The sun was shining and it was pleasantly warm out. I had nothing to do other than drink tea and read, but with the close of one trip, and this one was most definitely over for me, I started to think about what I wanted to do during the upcoming summer. Aconcagua had been foremost in my mind for a long time and now that there was only a walk out and a week in Mendoza left, I could once again think freely for a while.

The day slowly passed and I alternated between the tent and the sun, reading a trashy book called Shantaram that Kevin had hauled up to basecamp. I still had plenty of Solzhenitsyn left, but Shantaram read like a television show, which made it easy to kill time with. It was Christmas Eve and as the evening drew close the celebrations began, with the local guiding services throwing bottles of white gas into burning trash barrels. The resulting explosion brought forth lots of laughter from them. And on and on and on, with thumping music and, no doubt, dancing. I was glad someone was having a good time, though. I was bored stiff and welcomed sleep when it finally came.

Yet another Christmas spent abroad. I don't hate a lot of things in the world, but Christmas is one of them. At least the Christmas that we in the States celebrate. When I left the only references to Christmas were in terms of stores and how they were suffering, and how families had to cut back to spending only $5000 for presents (instead of $10000), and parents economizing, etc, etc, etc. Christmas turns my stomach and the crass materialism that we normally experience in the US is vaulted to truly obscene vulgarity in the season to be stupid. And so I go abroad. In fact, the most memorable Christmas I ever spent was in Nepal high in the Himalaya, near Mount Everest. I was the only guest in a tea house and as such the father of the family (the mother was working in a village lower down) brought the children out and we sat around the stove and ate potatoes while I drank a few cups of chang, the local homebrew. Or there was the time in Syria (Hama, to be precise) when every Muslim I met on the streets wished me a good Christmas. The holiday had little meaning for them, but the fact that it was supposed to be important to me, and they wanted me to feel welcome, made me appreciate the holiday.

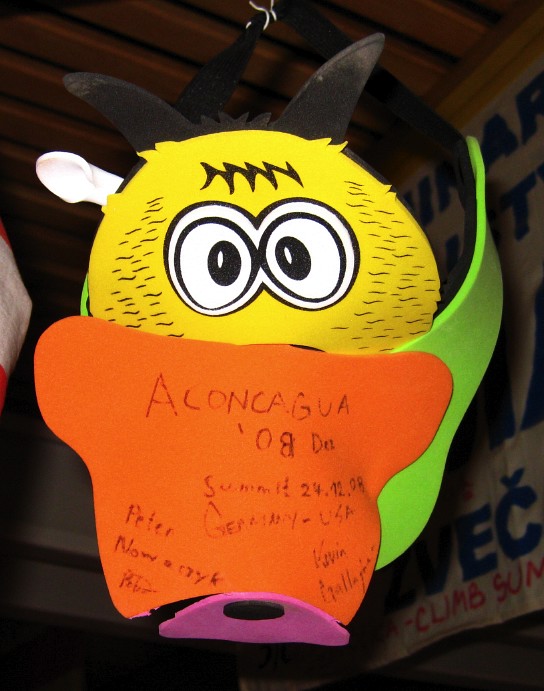

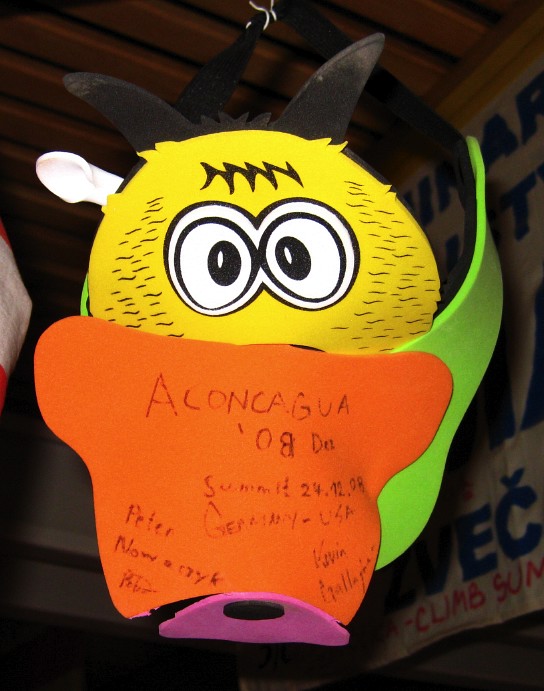

I spent the morning drinking tea and reading, and then drinking more tea. Around 1 pm I had finished eating one of my now superfluous dinners and was getting ready to take a nap when some one called my name. Looking around, I spied Kevin with an enormous pack on his back and a huge grin on his face. He dropped his pack and began to relate their story. With the storm coming they had decided not to put in a camp at Berlin, but rather to try to summit all the way from Nido des Condores, a lift of about 5,000 feet. Yesterday they had stood on the summit, the highest people in the world (few people climb in the Himalaya in December to heights approaching 7000 meters), after a 12 hour push from Nido. It took another nearly 6 hours to get down and was the hardest thing either of them had done. Peter stumbled into camp with another large pack and off we went to the refugio for wine and steak sandwiches.

One bottle of wine turned into two and all the wounds and hurts were forgotten. Peter and Kevin attracted the attention of a few hopeful climbers, but the main season hadn't yet started and we were able to eat and drink in peace. It was a big moment for the two of them. There was no way I could have summitted directly from Nido and was still happy with my decision to come down, just as they were happy to have summitted.

With two bottles of wine in us, and with the elevation, we were pretty happy on the walk back to Plaza des Mulas.

The storm was coming in early and it was clear that they had made the right choice about summitting directly from Nido: The upper mountain was in the middle of a storm that would have hit them about the time they were on their way down when they were most tired and most vulnerable.

We made plans for tomorrow: Up early, pack, hike to the road, and get a room, shower, and cervezas at Puente del Inca. It was a fine plan. In the evening the storm rolled off the upper mountain and gave delightful light. I did what could with the dinky camera I was carrying.

It was time to turn in, for with the loss of the sun came the usual drop in temperatures. We had gotten two people on the summit and I was happy that they had made it. But I was looking forward to getting out to town tomorrow and enjoying a beer and food that hadn't been made in a factory four years ago.