Doing Time

Doing Time

March 24, 2008

Dawn in the desert. I love this perfect time. Being cold, though, I bury my head in my sleeping bag and flop over on my side, looking out of a small blow hole with one eye at the land across the way. Looking at the sun and the rock and the world beginning anew. I watched the world for thirty minutes, sometimes conscious, other times not, before finally coaxing a hand out of my blow hole to my stove, strategically positioned last night. Working with the one hand stuck out of the blowhole, I got water for tea boiling and then waited. And waited. Andrew was somewhere. It was nice not to have to worry about him. The water finally boiled and I started the tea, with my one-arm-out-of-the-blowhole, steeping, wondering about what the day would bring. Not trepidation or fear or anxiety or nervousness. Anticipation.

An hour later I was standing around in the first set of clean clothes that I had worn since leaving Washington four days before. The sun was out and I was drinking more tea, doing not much of anything, as I prefer to do when I can. Which is most of the time. In a week people would be asking me what I did for spring break. I'd tell them that I did as little as possible. Did nothing, in fact. They'd scratch their heads in puzzlement and ask me if I was bored. I drank some more tea and pondered the different sex outhouses that the BLM had seen fit to install.

You'll have to put up with this skipping around stuff, but I can only write so many words about nothing. By 10 am we were geared up and ready to go. Mmm. A bit too far. Let's back up a moment so that I don't lose anyone. Andrew's brother Nate and his friend Tera had driven down from Missoula in one long push, arriving shortly after midnight. We had spent the morning getting gear organized and driving back to US 89, along it, and down the dirt and a gravel road road for 8 cush miles to the Wire Pass trailhead. We had a pretty simple plan. Hike down Buck Skin Gulch, supposedly the world's longest slot canyon, to where it joins Paria Canyon. Hike down Paria Canyon to a not-so-certain spot where we could climb out and get back onto the rim. Then hike cross country through the open desert to the Wave, a famous rock formation, and eventually back to the cars. None of the BLM rangers or volunteers had heard of anyone doing anything like that. But it seemed so obvious that I knew it wasn't original. Besides, it was Brian's idea.

The sun was bright and the air warm, but I kept a thermal top on, certain that once in the shade I'd be happy to have it. The parking lot had many cars in it, but the Coyotes Buttes and the Wave, accessed by the same trailhead, would probably siphon off most of the traffic. Starting hiking at 10:45 am in the warm sun was such a diversion from the usual Washington standard of starting at 3 am and climbing all day in the rain and snow that I didn't quite know what to do with myself. I grabbed a handful of sage and crumpled it in my hand, smelling it occasionally.

We dropped into Wire Wash and began the slow, sloping descent toward Buckskin Gulch. I hiked along with Tera talking about common experiences in the northern Rockies of Montana. She had been working for the Bob Marshall Wilderness Foundation, a non-profit group dedicated to protecting and preserving the massive wilderness complex called, by locals and hikers, simply The Bob. She worked building trail as well as bringing in and coordinating the efforts of other groups. I had traversed the length of the Bob in 2005 during my aborted hike of the Continental Divide and we had a lot to talk about.

Like a lot of Westerners, Tera wasn't originally from Montana, just as I wasn't originally from Washington. Tera grew up and went to school in Ohio. A midwest kid like myself. But once the West gets into your blood, which can happen with a single trip, it never gets out. Like a parasite. She'd been living and working in the northern Rockies ever since, only occasionally going home to Ohio.

This is how it is with the West. One trip to the Wind River range of Wyoming in 2000 was all it took for me. Andrew grew up in Tennessee. Nate did also. But now we live in the West and no one has plans for going elsewhere. The West is intoxicating in a way that nowhere else seems to be and the diversity of landform, culture, and society make it perhaps the most intriguing place in the world. The people and their history are different from the East. The settled East. The cultured and civil East. The East looks to Europe for inspiration, for history, for culture. The West, though, is the West. The West is indigenous Americana, a sort of mongrelized bastard of whatever culture happened to float through over time. Indian, Mexican, Mormon, Scottish, English, French, Japanese, Chinese, Islander, Russian.

The West is diverse, nonhomogeneous. I live in the Puget Sound area, a large metropolitan area as urbane as any in the world. Drive for 60 miles across the mountains and you're in ultraconservative ranger and farmer land. Utah is as different from Oregon as possible, despite their proximity. How different, really, is New York from New Jersey? Are Alabama and Mississippi that much different, culturally or physically? But what about Southern California and Northern California? California east of the Sierra versus west?

Nowhere else in the world would you find a place as freakish as southern Utah, except maybe northern Arizona. The rainforest that begins in my neck of the woods and stretches more than a thousand miles north through British Columbia and Alaska can be found nowhere else. There are more things alive there than anywhere else. It has Biomass. Where else, except the West, can you walk for nearly 200 miles without crossing a road, of any kind, completely on public land. Land for all. Open to all.

People, especially Americans, like to think that the United States of America is unique because of its political system and the freedom it gives to its citizens. We are free from being locked up without cause, can't be tortured, and will always have a speedy day in court. At least until a few years ago, that is. But, no, it isn't the system that is unique. It is the size and scope of the reserve of public lands that is. Nowhere in the world is there so much protected land, open and free to whomever wants to come. I am the largest landowner in the world. So is my mother. So is the cute blond girl in pigtails.

Not all of our public land is looked after in a manner that I like. Occasionally people want to "improve" it with drive in campgrounds with sex specific toilets. I think it is criminal to charge $25 to get into Mount Rainier National Park. The millions of dollars spent on a new visitors center is pure waste. When the BLM allows a new coal or bauxite or uranium development I cringe. But for the most part things seem to be getting better and not worse. Except for higher entrance fees. But I digress.

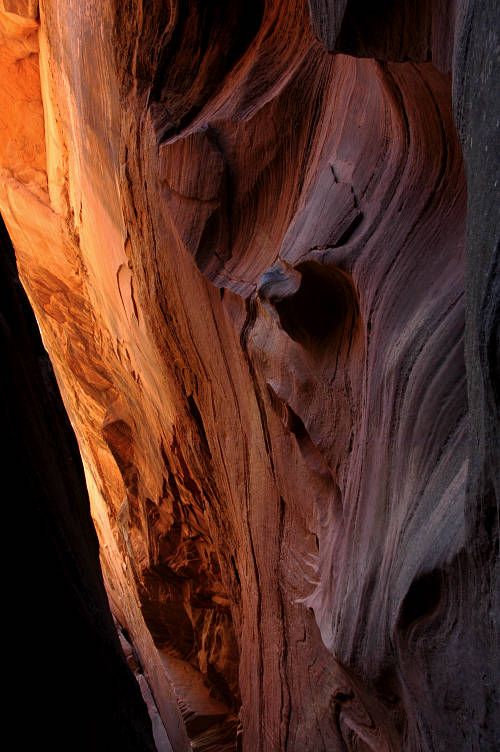

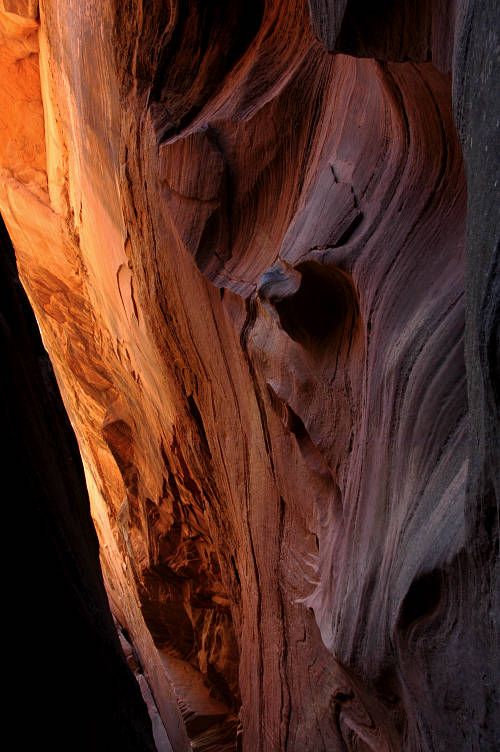

We had been walking for perhaps two hours. Through the tight walls of Buckskin Gulch I had wandered in a fit of amazement at the preternatural form of the land and the colors that the light, when it shined, brought out.

The rim, the world, the outside world, was far above us and almost out of sight. The four of us moved at our own pace, sometimes with others, sometimes alone. I didn't have to keep an eye on anyone and could just meander and gawk and ponder and be amazed. I could do all those things that make being a human so rewarding. For all I know crows and ravens and wolves do the same thing. But I can't believe that a cow, a herd member, ever contemplates anything beyond the cud.

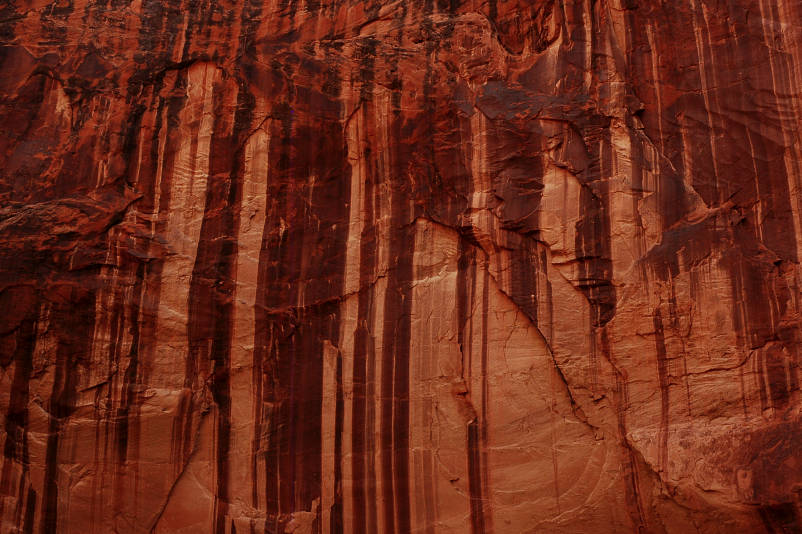

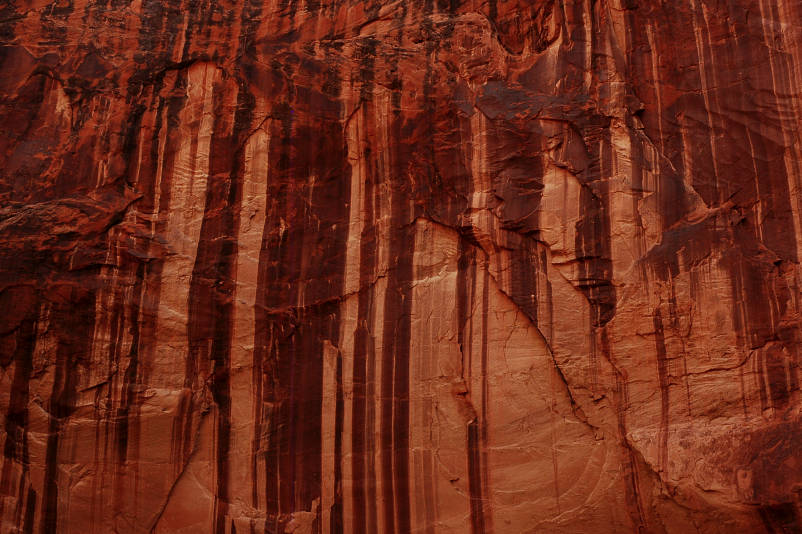

The canyon that we were walking through was clearly carved at some point in the past by a river that no longer flows. The sandstone rock in the area was soft enough to carve, almost, with your fingers and water had no difficulty eroding it into forms beyond the imagination of even the greatest of all artists. Dig that. Water flow, a completely scientific force, has more imagination than the most creative artist. Occasionally a bit of soil would get stuck in a crack and a seed would happen to drop in, bringing a sprig of green to the ochre walls. Life expands and explodes. That is what is does. You cannot keep it back or try to control it. To try is to fail. And failure might kill us all. Better not to try and let some die, rather than all.

I stopped at the far end of the football field sized widening in the canyon. I stopped and listened. Andrew was singing, and the rock was changing the sound. The song, or chant, or prayer, or whatever it was that Andrew was giving voice to, floated to me softened, gentle, warm. What could a group of chanting monks do in here? And this wasn't even the best spot. Andrew had stopped to sing at many such places. Indeed, all of us had been breaking out in spontaneous song since we first entered the gulch.

The songs that I sang had no meaning, no structure, no form. I could never remember all the words to any song and wasn't creative enough to make up my own. So I took and borrowed, horrifying the writers and singers. Sometimes I sang for myself. Other times so that others could hear, the rock walls changing the sound from something pathetic into something beautiful. In this place, at this time, it was hard to imagine that there was any ugliness in the world.

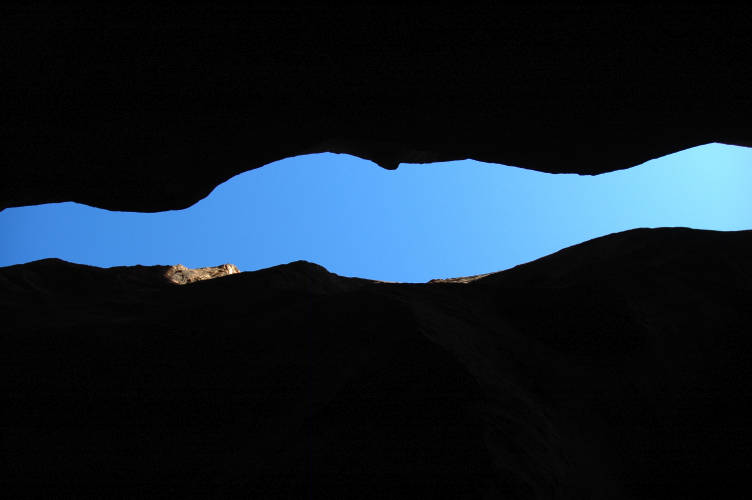

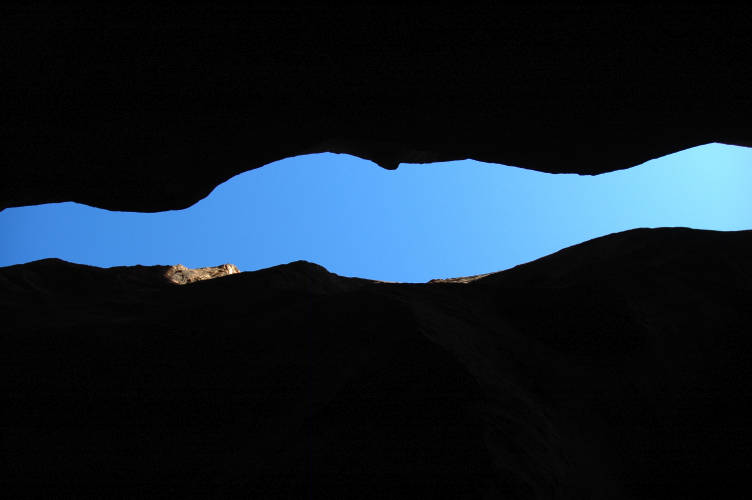

I had been sitting, alone, for a half hour, drinking tea that I had boiled up in a patch of sunshine that warmed my skin while the tea warmed my insides. The others were behind. Elsewhere. I looked at the walls and realized that I was in prison, doing time. I couldn't escape from where I was to the outside world without the passage of time. I was confined here until I was let out. If we couldn't find the cattle trail out, I wouldn't see the open sky for another three days, when we emerged at Lee's Ferry. I shuddered at the thought of the hitch back to Wire Pass. We better find the trail.

The others arrived, lunched, and we moved on. We were making steady progress downcanyon but had no way of knowing where we were in it. I was going by time. 15 miles from Wire Pass to the confluence with the Paria. 15 miles at 2.5 miles per hour. Let's see, that would make for 6 hours of walking. Add in a gawk multiplying factor of 1.45 and you have 8.7 hours of walking. Toss in another 15 minutes of break time every...

Seriously, I know people who plan trips that way. There was this one dude at ADZPCTKOP2005 who had made a rigorous itinerary for his 2650 mile hike along the Pacific Crest Trail. May 9, 2005. Wake up at 6 am. Eat 400 calories. Weather predicted to be warm and sunny. Hike for 2 hours and cover 5.75 miles. Reach Bunny Spring and consume 0.8 liters of water. Apply sunscreen... In an undertaking that was supposed to embody the ideal of Freedom, he had shackled himself to a plan. Later that day he was convinced of the error his ways and gladly tossed out the plan to see what the day would bring instead.

The best planners I know look at things carefully, objectively, realistically. They figure out what they need to go where they want to go. They make a plan and consult with others who have done the same thing or similar things. They spend time pouring over maps and guidebooks and, now, satellite images. They do all these things and then throw it out when they start their trip. They know the options and the possibilities, but are open to doing something new and different. They rely upon themselves and their ability to work through any difficulties that might arise. Instead of trying to control everything, instead of being pro-active, they react instead. They trust their own abilities and really do look upon a problem as an opportunity. A thruhike should be required of any MBA. Of course, most would die in the process, either of their own foolishness or by the hands of other hikers or locals, but fewer MBAs would probably be a healthy thing for our country.

I could feel myself drifting along as I hiked. Not physically, mind you, nor mentally. But, rather, I felt the sort of spiritual drift that hadn't happened in a while. The sort of drift that occurs only when you have nothing to do and all the time in the world to do it in. I had felt it before, on other trips, with other people, in other places. A drift toward a future in which there was no future. First, let go of your past. Then let go of your future. Finally, let go of the present. A Buddhist monk in Thailand had told me that.

I had read about it in the works of certain authors, like Abbey and Kerouac. I had seen it in art galleries. I had heard it in music. The drift. Almost like gravity, a force that is always working on you whether you realize it or not, the drift is toward something better. Odysseus knew about this Thing. He had heard the Sirens' call. His men had tied him up beforehand, though. Good thing, too. He would have died of drowning otherwise. But he would have died a happy man. Life was strange like that.

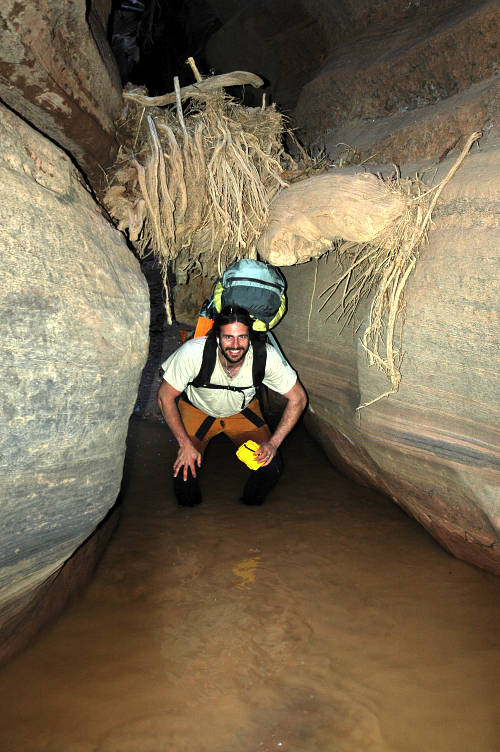

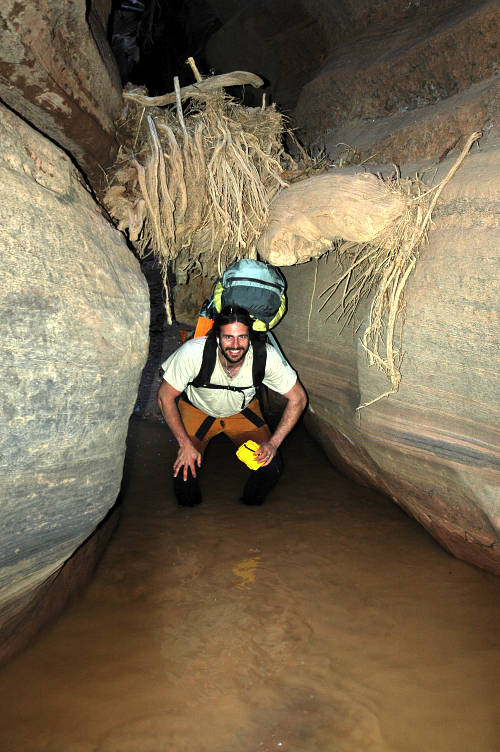

This pool was deeper than usual, I thought. I was in up to mid thigh in water that a little above the freezing level. Probably the Cess Pool I had read about in a worthless guidebook. If so, we were getting close to the confluence and the end of our day. Good thing, too.

I was getting a bit tired. Not so much from hiking, as this was the easiest hiking I had done in a long, long time. There was something almost oppressive about the tight confines of Buckskin Gulch. Again, the thought of a prison and a sentence of fixed duration. I hadn't been able to see the horizon for some time now, and the open sky, the open land, was the very definition of freedom for me. Not being able to see it was beginning to wear on me. Andrew never stopped smiling.

Tera and Nate were somewhere behind. Andrew and I walked along together talking about the past and about people we knew in common. On previous trips to the Southwest I had gone with others who needed me to look after them. To help them. To comfort them. It was nice not to have to do that now. To simply be in a place and a time and be myself. To be.

Andrew and I picked our way through a confusion of boulders and down trees, following an obscure course. I began to edge my way over a drop off when I felt the sand I was standing on begin to give way. I jumped to the other side, landing with a thud on the safety of firm ground. Probably would only have a little concussion, I thought. Andrew went another way. I scouted around and found that we were at the top of a set of dry falls. Two anchored ropes led down to the bottom. Both were mostly cut through, but they would have to do.

Andrew and I shimmied down the ropes and waited for the others. Not being able to see them, we eventually had to shout our way through a sequence of directions to get them to the ropes. They came down in fine order and we began the last, short stroll toward the confluence. My worthless guidebook had mentioned these ropes and actually said where they were in relation to the confluence and we knew that it wasn't far to the end.

The walls of the Gulch were getting further apart and even higher. Becoming majestic rather than oppressive. The trickle of water that we had been following for a while slowly grew to a steady flow about an inch deep. Closer. We broke out into a comparative open where a large growth of green beckoned us. We were home for the night.

Two hikers were ensconced at the top of the mound and so we took the lower campsite. As developed as it should be, it had no amenities. Just as it should. We could get water out of the trickle. There was open ground. The first thing I did was pull out my liter of 120 proof rum and make a cocktail. I sat drinking my cocktail (rum straight up, out of the liter bottle) as the others milled about doing various tasks. The light slowly faded away. I drank rum and soup and tea and ate dinner, complete with chocolate and more rum. Andrew passed around the whiskey. The land was completely dark when we first heard it. Barely. Gently reverberating off the canyon walls was the softest, most plaintive sound I had ever heard. The hikers on the top of the hill were playing a musical instrument as quietly as possible, not wanting to disturb us. I sat, and strained my ears listening to the intoxicating sound.

It was warm out, even without the sun on me, even in the shade of the canyon, even without tea in me. I crawled out of my bag and into the open air, scratching myself and wondering. About what? Just wonder. I started water boiling and ate some chocolate covered, chocolate chip granola bars that had come to me for $1 per 10. I had twenty of them for the four days. And six King Sized Snickers. I had lots of good stuff. I took a pull of rum to celebrate the morning. What's the purpose of being on vacation if you can't have a drink with breakfast?

The morning rolled. No one was in a hurry to go anywhere, especially as we had a short day planned. Just a few miles. Maybe 8. A short day's walk to where we could, probably, climb out to the rim above and escape this exquisite prison. Nate tried making pancakes, but ended up with something that looked more like scrambled eggs. He dumped maple syrup on it and ate it all. It took nearly three hours for us to finally start on the day's activity. I took another pull of rum for the start and we passed around a carrot for good luck and Godspeed.

We had camped a quarter of a mile from the confluence of Buckskin Gulch with Paria Canyon and made the walk to the river in short order. The Paria was muddy, just as it was a few days ago when Andrew and I went exploring on the upper reaches of it. Now, though, it was buried deep within a canyon, a canyon that was no longer oppressive. It was, however, frigid.

The Paria was icy cold and the canyon was still narrow enough that we walked through water as often as we walked on dry land. The sections in between water walking were long enough for my toes to regain feeling, but just barely. Occasionally we'd hit sunny patches, but even in the shade it wasn't too bad. At least if we weren't in the water for more than a minute at a time. There was a lot to see and do along the river, with interesting caves and tunnels and strange arches and arches to be littering the walls. We didn't make much progress down the canyon.

The Paria sources well north of where Andrew and I went exploring and flows for some ways south of where we'd leave it, ending its run at Lee's Ferry on US 89A in Arizona. Lee's Ferry is named for John D. Lee, a Mormon pioneer and driving force for the LDS settlement in southern Utah. Lee, however, is known more for other activities than the building of towns and communities in a hostile land. He is known as the architect , or scapegoat, of the Mountain Meadows massacre.

The LDS arrived in Utah in the late 1840s and began settling the area, which was a sort of no-man's land belonging in theory to the United States, at least after it was stolen from Mexico in the Mexican-American war. One reason for settling in the Salt Lake area was to be far enough away from the prying eyes of the gentiles (ok, so the Mormons had been killed in the past by gentiles, just as they had spilt gentile blood) and the arm of the federal government, but still be close enough to the rapidly forming settlers trails to Oregon and California to not be completely cut off. The LDS would control a crucial staging area for making the final push across Nevada to reach California.

By the late 1850s the LDS was increasingly in conflict with settlers passing through "Deseret" on their way to California and with the Federal Government in general. For one reason or another, a particularly large settler train was passing through and the LDS militia (the Nauvoo Legion), led by Lee, attacked. The settlers fought the Nauvoo Legion to something resembling a stand still, endured a siege, and finally surrendered under guarantees of protection from Lee. They were promptly executed. More than 100 people died. The Nauvoo Legion did allow 17 children too young to remember anything live.

The Feds were none too happy with the state of affairs and, nearly twenty years after the events (the Civil War sort of got in the way), John D. Lee was convicted of the crime and shot on the sight of the massacre. He is looked upon favorably by historians of the LDS. Hey, enough morbid stuff! Take a look at the cool crescent moon carved into the rock above Andrew!

We had stopped for lunch in the sun on a sandy beach, lounging indolently, just as good vacationers should. After having some carrot for lunch, Tera and I set off on our own for a bit as the brothers Phelps lingered a while longer at the beach. We strolled along through the water, which had now warmed to something almost pleasurable, and along the beaches, admiring the arches and other oddities that the land held. A long row of moss and ferns grew directly out of the rock wall beneath an arch-to-be. There was no soil, no crack, no nothing. Just moss and ferns and a little seeping water. I heard Andrew singing faintly.

Tera and I had been walking for forty minutes, occasionally hearing sounds coming from upcanyon that sounded like singing. Just as we were about to go around another bend, I heard Nate's hysterical voice. I had just crossed over the river and Tera stopped a few feet short of the bank to see what he wanted. "Keep moving Tera, you're standing near quicksand, " I said. She rapidly got on shore.

For most of the day we had encountered squishy patches of ground in the river where our feet would sink if left there. Sometimes a little muscle had to be used to get out of the muck, but usually only a very little. Having been stuck in quicksand before, I knew that it could be a pain to get out of without the help of others, but that usually you could avoid being stuck completely just by keeping your legs going.

Back to Nate. He came bounding around the previous bend, shirtless and frantic, screaming for us to come with. "Andrew's stuck in quicksand!" he shouted. "Run, hurry!". We dropped our packs and started running back the way we had come. We ran and ran and ran some more, running all the way back almost to where we had lunched. And there was Andrew, stuck in the water with a hat on to protect him from the sun. Andrew had been exploring near a cave in the river and on his return went straight in to his knees in quicksand. No warning, no slow descent. Just a lightning drop. Nate had tried to dig him out but couldn't move enough sloppy muck to get Andrew free. So, he did what any brother would do: Run us down yelling all the way. Tera and I stripped down and waded out to Andrew, being careful not to get stuck ourselves. Crouching down in the water, we dug at Andrew's leg, pulling sand away as rapidly as we could while Andrew tried to pull his way out. A minute of effort and we still couldn't get him out. I grabbed his arm, the others dug, and pulling with everything I had, we eventually wrenched him free.

I sat in the sun and enjoyed a good rest. The others did the same. Occupational hazard, like falling into a crevasse on a glacier. Andrew wasn't bothered by the experience, but his leg was a little sore from the effort and I imagine his wrist hurt a bit as well: I had been pulling on it with full force. We eventually began the stroll back to where Tera and I had left our packs and for the rest of the trip kept (mostly) in sight of each other and away from the rocks or walls while in water.

It was pleasant to retrace our steps again. The canyon was just that good. It had taken on gigantic proportions now and held a more gothic, soaring feeling to it than Buckskin Gulch. The Paria seemed like the playground of some huge giant, while Buckskin was where the snakes that tormented the giant went to hide from its wrath. Strolling along, we saw the Family once again, two of them anyways, looking confused in a patch of willow. I haven't mentioned the Family yet, having wanted to store up everything to tell at once.

We met them yesterday at a sunny place a few miles from Wire Pass in Buckskin Gulch. We were looking for a way to climb out to the rim to visit a freakish formation called Cobra Arch. A nice, short side trip that was in my stupid guidebook. We came across the Family, as I'll call them, at what we thought was the appropriate place to climb out. It looked easy enough, but the matriarch of the Family told us confidently that it was not. She had been here before and this wasn't the place. It was another mile down the Gulch. We left her and the others to their leisure and pushed on. We never found the place and concluded that she had been wrong. Later on we would pass her sons, looking confused and wondering where they were supposed to camp for the night. They were supposed to camp at the way out to Cobra Arch. The whole Family trailed past our campsite last night looking tired and dejected. They had covered that day what they had planned to cover over two days.

We saw them this morning again, and then yet again at a terrible water source. They were slowly gathering water from a mucky pool (about two liters in volume) that was being filled by a trickle from a seep in the wall. They had been there for some time getting water and eating in the cold shade, on top of wet, muddy sand. Maybe the worst lunch spot in the Canyon. When we approached, thick clouds of smoke were coming off of their stoves. Apparently they had eaten a large quantity of anchovies for lunch and didn't want to deal with all the oil. So, they put the tins on top of their stoves and burned everything up. The air stunk. Stank. Just like in Page or Trona or Gary. We took about a liter of water from the seep and then left, despite being low on water. The Matriarch didn't think this was a good idea and told Andrew as much. After all, this was the last spring and we would be wise to spend some time filling up here. We left anyways and walked a quarter of a mile to where there was a huge, enormous, edenic, gushing spring in the sun, with lots of dry sand to sit on. How the Matriarch could have confused her spot with ours, given that she had been here before, was stupifying. We sat and rested in the sun, drinking the sweet water, as they filed by. One mumbled something about having stopped too soon yet again.

So, this brings us to this latest encounter. The Matriarch and one of the men were milling about in the willows looking confused. With all of the phenomenal campsites in the area, they had chosen a truly awful one. We went ahead of them and encountered another member of their party returning to the willows. He didn't look too happy. "Stopped too soon again," he muttered in passing. We continued on for a quarter mile to a huge beach with trees and grass, under a massive arch. We were home. The Matriarch's "knowledge" of the place was causing them to stop too soon, or misread landmarks. Sometimes it is better to know nothing, or at least have new eyes. We estimated that we were close to our climb out point and Nate, Andrew, and I went ahead to find it, leaving Tera to guard our campsite, though there was plenty of room close by for the Family, who would surely come up from their willows.

The three of us walked along with the dual goal of finding the start of the way out and a possible water source, not wanting to have to filter the muddy Paria. Ten minutes down the river and we found the first, but not the second. The Paria would have to do. We returned to our grand campsite and found only Tera comfortably ensconced. The Family had, apparently, decided to stay where they were in the willows rather than walking for another 5 minutes to a much better site. I set up my bed for the night. It took 2 minutes, including the time to took to have three swigs of rum. Vacation, you know.

Although life was pretty good now, water was something of an issue. We needed enough to get through all of tomorrow and half of the day after that. My estimate was for 4 liters a piece with a little extra. It wasn't especially hot, even in the sun, and our water needs shouldn't be that high. The problem was that the Paria was very hard to filter and we needed a lot of water. Our two gallon jugs and by water bags were filled with the mud and left to settle out. Hopefully we could get enough for the days ahead. We sat around and filtered and ate dinner, complete with carrot and rum and whiskey and chocolate bars stuffed with caramel, and talked and kidded and explored the rock formations in the area. I spent an hour staring at the arch above us. The peace was almost too much to handle.