El Salvador: La Palma, Suchitoto, San Salvador

January 3, 2003

The bus ride from Gracias to Nuevo Octepeque, near the Salvadoran border, was jammed full when it picked us up and we had to stand in the aisles, although after 30 minutes I was able to get a seat. Mike and Andrew had to stand for the entire trip and none of us were in particularly good spirits when we reached the border, although happy to get off the bus and onto the ground again. We hopped a taxi to the border crossing at El Poy, which turned out to be smooth and efficient, although Mike had to shell out $10 for a tourist card. Andrew and I had both arranged for free visas before leaving our respective countries and so got in without a hitch. We found a cantina on the Salvadoran side and popped in for a short celebration over a few beers and some chicken. I had just crossed into my tenth country and Andrew his 100th. Mike was somewhere in the 60s or 70s and couldn't quite remember. I tried for a while to guess a country that Andrew had never been to, but was unsuccessful.

Our celebrations over, we got onto a brightly painted, uncrowded bus with pleasant reggae music playing and started the ride to La Palma. I was rather surprised at the occupants of the bus. In Nicaragua and Honduras, we were clearly the foreigners. However, in El Salvadar, most of the people looked like I did: Fair skin, light brown, or even red, hair, beards. If I spoke Spanish and wore different clothes, I would have fit in just fine as a local, as would have Andrew. The forty five minute ride up and into the hills to La Palma was a relief from the crowded bus in Honduras and the scenery became dramatic almost immediately. It was also noticeably colder than elsewhere in Central America.

The bus dropped us off in the center of town, which seems to be something of a tourist place for people from the capital. We got a room at the mostly empty Hotel La Palma for $10 each and, except for the lack of hot water, it was really quite nice. In the 1970s, La Palma was the home of Fernando Llort, an artist of some fame, and his art style decorated the wall of the hotel and various buildings around town. He employed a very simple technique to depict villagers, Christ, and the surrounding mountains and the town has since made a living copying his style onto everything from wooden trays to T-shirts.

After settling in we made the requisite stroll around town to look at the various crafts that the town makes, some of them quite good. Nice chess sets and brightly painted housewares, all of which might make nice trinkets to give to people back home. Our sightseeing done for the day, we retired to the hotel's restaurant for dinner (grilled chorizo with onions, peppers, and rice), although it was so cold out that we didn't stay for more than a beer a piece.

After a tasty breakfast in the hotel restaurant, we set out down the road we had come in on to walk to San Ignacio, a village about 4 kilometers to the north that had seemed rather pretty when we rode through yesterday on the bus. Pleasant walking under bright blue skies and a stiff breeze, but somehow a little sad. Unlike the Nicaraguan and Honduran countryside, there was little evidence of domestic satisfaction. Indeed, there did not seem to be the same small-farm environment that had made the previous two countries so pleasant. Northern El Salvador had borne the brunt of the most vicious fighting in the 1970s and 80s between the government and the FMLN, the rebel group that had plagued the government for years. One of Oliver Stone's first movies, Salvador, depicts some of this battle and is well worth watching. After the fall of Nicaragua to the Sandinistas, the Regan government was not about to let neighboring El Salvador fall into similar hands and stepped up its military assistance to a very high degree indeed: For a time in the 1980s, El Salvador was the third largest recipient of such aid, after only Israel and Egypt. Both sides fought in a particularly brutal fashion and the scars upon the society were still quite evident.

San Ignacio was a pretty, but sad, town, although I unfortunately decided not to bring my camera along with me. There were several great murals, including one that took up an entire side of a house and depicted Che Guevara, Farabundo Marti, and Oscar Romero. Marti was a founder of the Central American Socialist party and led an uprising in the countryside in the 1930s against the government for reasons that are almost universal in Latin America. The government responded to the uprising by slaughtering anyone who looked like they held some Indian blood or sympathized with the rebels. Estimates of the dead range up to 30,000 people. Marti was eventually captured and shot by the government, though would live again in the name of the FMLN. Violence flared again in the 1970s and guerilla activity in the countryside led to the creation of paramilitary death squads to try to deal with the insurrection. A coup in 1979 promised reforms, but these, for various reasons, were never carried out and in 1980 open fighting broke out after the assassination of Archbishop Oscar Romero while he was giving mass in a chapel in San Salvador. Romero had been a vocal proponent of peace and an opponent of much of the landed class in El Salvador and his assassination, in church, provoked much outrage.

Although the rape and murder of four US nuns, who were providing aid to the suffering in the countryside, slowed US military assistance, the event was quickly forgotten by the Regan government in its crusade to stamp out communism. The Soviet Union, through Cuba and Nicaragua, funneled money and arms to the rebels in their attempt to gain dominance in the New World. The people of El Salvador paid in blood for the two superpowers rivalry. Massacres became frequent, with at least one gaining some international condemnation: The killing of 900 men, women, and children in the village of El Mozote. In 1992, after twelve years of open fighting, the FMLN and the government sat down and signed a peace treaty, although it was more of a capitulation on the part of the rebels. The promises of land reform were never fully implemented (giving unfarmable land to peasants), investigations into the numerous human rights abuses stymied by pardons, and the death squads dismantled, only to be absorbed into a new national police force. Over those twelve years, an estimated 75,000 people were killed in the fighting, funded, in part, by six billion US taxpayer dollars. As a final cherry to top off such a wonderful sundae, the first postwar president was sworn in amongst cries of fraud. He belonged to the party of choice for the death squads, the ARENA.

I thought much about the legacy of brutality that hung over the countryside of northern El Salvador on the walk back to La Palma, although a custard-cake-pie at Soni's Cakes made me feel a little less gloomy. Only a little less. After lounging at the hotel for an hour, we went out to get some lunch. A man was sitting on the other side of the street, clearly stinking drunk, with a partially empty bottle of clear liquid next to him on the curb. A few other drunk milled about in the alleyway next to where he was seated. After eating and returning to the hotel, we found that the drunks had shifted sides to where it was shady. One had a bloody head, but didn't seem to mind too much. The others still milled about. Nicaragua had also fought a long and bloody civil war, but there had not seemed to be much sadness there. Nicaragua had seemed a hopeful place. Despite the trappings of La Palma, Salvador seemed to be a place without this best of human qualities. I did not know why, and perhaps didn't want to know.

After a siesta we emerged from the hotel to buy souvenirs and found that the drunks had gone elsewhere for the afternoon. I bought a bright red carved box and a pretty black tray that had been painted with a base of black and with nice flowers on top of the base. Despite the fact that, according to the guidebook, seventy five percent of the town makes its living from producing and selling such things, I felt a little awkward about buying them. Not because they were touristy things (indeed, they were quite nice), but simply because of the air of depression that hung over the town. I would be happy to leave such a sad place tomorrow for our last town in Central American before going to San Salvador to fly home.

My morose feeling from the day before was with me in the morning, and I was actually happy to get onto the bus heading for Aguilares. The guidebook didn't mention it, but it turned out that there was a bus from Aguilares to Suchitoto, our destination for the day, thus saving us from a ride all the way to San Salvador in the south, then back north to Suchitoto. This we found out from the fare collector on the very crowded bus to Aguilares, though, as it was a commuter bus, we quickly got seats. Unfortunately, Andrew and I were sitting behind a young man who was motion sick and vomited rather frequently out the window, spraying Andrew occasionally. The 90 minute bus ride was thus spent hiding from vomit and trying to keep sane as the fare collector came down the aisles, shoving those without seats to the side.

Aguilares wasn't much of a town, but it being a Sunday, the market was thriving and, this being Central America, we were mostly left to ourselves, barely garnering a glance from the locals. I begged for such anonymity last winter in Kathmandu. After making a few inquires, we finally located bus #163, a block off the highway near the local Red Cross office and got on to wait. After the highlands of La Palma, Aguilares, significantly lower, was really rather hot, and there was much dust in the air due to the market goers. When the bus finallly got going, the dust got worse as we moved slowly down the rocky, pitted road, at about 10 kilometers per hour. The bus quickly filled with dust, prompting the locals to put all the windows up, which we complied with, somewhat dubiously. Now, all the dust was trapped inside and with the windows shut, it became rather sultry inside. Eventually the windows came back down and I started to enjoy the slow bus ride. We went past many large farms, clearly not family farms, and many people got on and off on their way to or from work. In Nicaragua and Honduras, it seemed that many people had their own small plot of land and were able to raise food on it for themselves. In El Salvador, it seemed that people had to work someone else's farm in order to get money to buy food.

Each village we passed on the slow road had burned out, bombed out buildings. Bullet holes graced nearly every concrete structure. Organized soccer matches went on in fields that would have been unthinkable in the States. Finally, after two hours, the bus left the dirt road for a well paved one on the outskirts of Suchitoto. Our dust-ordeal was over, and we emerged from the bus coated in a mixture of dirt, dust, and sweat, looking extremely beat. This being our last town, we went over to the most expensive place in town, the Hotel Posada de Suchitlan, which the guidebook said was quite posh and whose Sunday brunch was supposed to be attended by San Salvador's finest. When we staggered in, the brunch was going on full swing and I could feel the eyes of most of the diners upon me. The hotel staff was a little unsure of what to do with us, and I got the feeling we were about to be told there was no room for us here. Andrew and I produced, almost automatically, several wads of US dollars. Everything was friendly after that and we were shown to our rooms in the resort. A fat $62 for the three of us, per night, for a great room off the main courtyard. It was our last town, after all.

After cleaning up we went for the requisite walk through town, stopping at a nice cafe with a view for lunch and afternoon beer. Suchitoto overlooks the Lempa reservoir, a massive creature formed by the damming of several rivers. I was struck by how barren the countryside was. Gone was the lush greenery of Honduras. This place, in the tropics, looked like California. Desert like. Dry. The hillsides had been stripped bare for wood. Valleys had been cleared for large, cash crop farms (coffee, indigo). Perhaps El Salvador was in a different climate pattern and what I was seeing was how things really were supposed to be. However, I could not shake the feeling that what I was looking at was the equivalent of an elevator in an outhouse.

Suchitoto was evidently a rather well-to-do place, and the murals on the walls reflected this. An occasional ARENA sticker or painting. A picture of Romero in pleasant surroundings. No Che. No Marti. After drinking down more beer at a local cafe with a nice view of the reservoir, we returned to Hotel for a brief nap before dinner. We made it in time to catch the setting of the sun, which was about as California-like as possible; the red glow of a desert sunset cannot be mistaken anywhere in the world. I was surprised, however, to find it in the tropics.

We went all out for dinner, spending $58 between the three of us on appetizers, drinks, and half-way respectable steaks. This was Andrew's last night with us, as he had to take a flight out of San Salvador a day earlier than we did, and would be leaving us tomorrow afternoon. We seemed to be the only diners that were actually staying at the hotel and, shortly after retirely, all the lights in the place went out and we were most definitely alone. We all went to sleep early, but were awoken in the middle of the night when the fire alarm in the room next to us went off. A little hesitant to go prowling about the courtyard in the dark looking for someone in charge (there were armed security guards during the day), Mike and I finally timidly walked around the place, but found everything locked up tight and with no one around. We had finally resolved ourselves to earplugs when a knock came at our door. The night watchman had arrived, but didn't quite no what to do and left a few minutes later. An hour passed, and a man showed up with a key to open the other room and turn off the alarm. Quite a bargin, that $62 we spent.

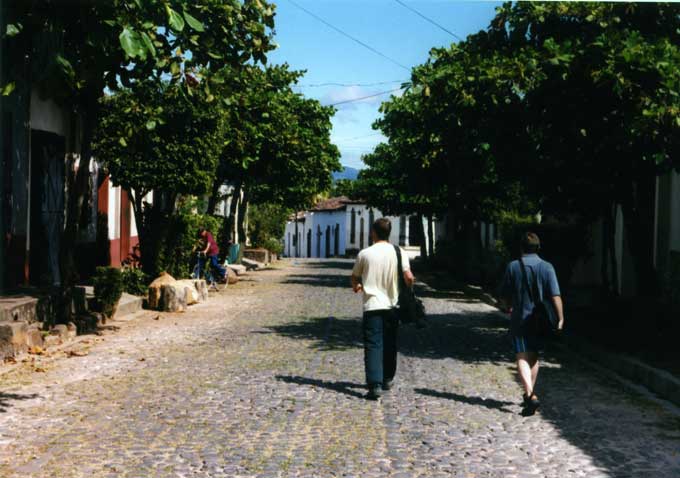

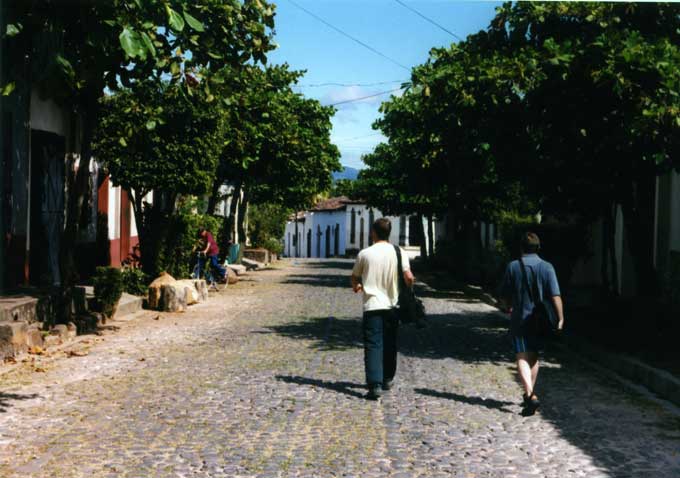

I wasn't super happy in the morning about staying another night in the place, but Mike and I agreed that it was easier than packing up and moving to another place. After a nice breakfast in the hotel, we set out for another walk around town, taking in a few sights that we had missed yesterday sitting in in the cafe. The main church gleamed white and made for a solid, scenic anchor to the plaza, around which loafed a few fellow tourists (all, apparently, from San Salvador).

We took a final stroll down toward the reservoir, passing through the residential section of town, but failing to reach the lake itself as there was a gaggle of kids swimming and frolicking in the water and we didn't want to disturb them.

We contented ourselves with walking along the banks, passing a few skinny cattle and the rare Salvadoran family farm, before heading back up the hill into town so that Andrew could catch an afternoon bus to San Salvador, exactly as Mike and I would be doing tomorrow. I was a little sad as I watched Andrew ride out of town on the bus. He had been a good traveling companion and an excellent foil to Mike. I wondered when I would see him again.

After a swim in the shallow pool of the hotel and a nap, Mike and I headed out for some last street food. I wanted to hunt up the national dish of El Salvador: Pupusas. A grilled, stuffed tortilla, I had to experience this last bit of street food before leaving Central America. Deep in the residential section of town, we found an old woman, attending to by her grandchildren, working over a propane fired grill making the local treats. We sat at plastic tables with the residents and spent a good hour devouring the treats, stuffed with various combinations of cheese, beans, meat, and eggs, washed down with several sodas. There was a lot of friendly activity in the neighborhood and other pupusa stands could be seen from our own, although I would like to think that the old woman was the best of them all. All told, the two of us spent $4, and had a meal that I thought significantly better than the fancy thing that we had the previous night at the hotel. In the blackness of the night Mike and I carefully (many potholes) returned to the hotel and got inside just before the night watchman shut everything up tight for the evening.

Mike and I sat around the hotel for most of the morning, partaking in the free continental breakfast and generally being lazy. We couldn't even manage a last walk out to the plaza for ice cream. By the time noon rolled around, we rallied and got our stuff together for the bus ride to San Salvador. The bus was very uncrowded and the kilometers rolled slowly by us, which helped the transition from the countryside to the heavy urban area of San Salvador. My nose began to twitch as the pollution increased. At the bus station we hopped out and straight into a waiting taxi cab, which delivered us to the Hotel Grecia Real, which had an interesting description in the guidebook and was supposed to be one of the better hotels in the area for the money. Unfortunately, $39 bought us a small, windowless, barely ventilated box. We waited for more than an hour for ham and cheese sandwiches. They didn't sell beer. At dinner, my potato had some sort of worm in it. We never left the hotel, as I didn't particularly want to deal with the urban setting of San Salvador, and instead watched soccer highlights on the TV, beerless.

We had made arrangements with the hotel manager to have a taxi waiting for us at 5 am to take us to the airport, which is about 40 kilometers to the south of the capital, one the coast. When we walked outside of the hotel to the waiting taxi, I was surprised to find it accompanied by not one, but two guards armed with shotguns. Apparently this is a fairly standard procedure in San Salvador these days. The taxi whisked us quickly through the empty streets and out to the airport in rapid order. Mike and I lined up at the TACA counter to wait for a boarding pass. The standard TACA antics ensued, although after 90 minutes a person in a TACA uniform came over and pulled me out of line, for some unknown reason, and got me through the process on her own initiative. After clearing security, without getting an exit stamp in my passport, Mike and I went to a cafe for some breakfast and coffee. Now that we were actually inside the airport, it didn't feel like Central America any longer. It felt like O'hare, or SJC, or any of the other innumerable airports in the States. Yes, the trip was most definitely over.