Mainline in the Grand Canyon

The Tanner and Beamer Trails to the Little Colorado, March 14-16, 2004

March 13, 2004

The sun was still at least two hours from coming up, but I could not sleep. The Kansas prairie was as still and quiet, as I was well off I-70 and was the only dweller in the state park. I had come far the day before, all the way from central Indiana, and had a long way yet to go today. I pushed the sleep out of my eyes and collected the empty beer cans that I tossed aside last night, wanting to get rolling again. The transition from the moisture laden MidWest, with its green farms and plentiful trees, to the arid High Plains, and eventually the Rocky Mountains, was one of my favorite experiences. It is one of the few things that is good to see from a car, because the change happens abruptly. It only took me a few minutes to pack up, for my room last night was the open sky, with a ground cloth and a sleeping bag and a sleeping pad as a bed. The green digital clock in my car told me that it was 5 am back in Indiana, which made it 4 am here. I found an all night gas station and bought some coffee and a doughnut before roaring onto I-70 to continue my blast toward the Grand Canyon.

The sun came up slowly, slightly purplifying the plains around me, and bringing to light the land that so scared the early American settlers of the continent: The Great American Desert. Land too dry to farm in any traditional way, and not enough timber to do any traditional building. Traditional wagon wheels dried out and fell apart. The traditional method of hauling everything with you for a home fell apart under the massive distances to travel. The High Plains, as Walter Prescott Webb convincingly argued, forced the settlers to adopt different rules and methods in order to be successful. Or, rather, it forced them to adapt if they wanted to continue to live. Gone was the lush, easy living of Trans-Appalachia. Nothing in the European experience in North America could have prepared the settlers, and they suffered greatly by trying to retain the old way in this New Land.

None of their difficulties caused me the slightest worry. My car roared down the interstate at a comfortable 80 miles per hour with NPR on the radio for company. I stopped once I crossed into Colorado to grab a greasy breakfast at a truck stop and was pushing hard once again. The formidable Front Range came into view along with the smog-choked pit that was the Denver Metro Area. The Front Range was not friendly to settlers and all the major settler routes ran to the north of it, through South Pass in Wyoming's Great Divide Basin. But the Front Range couldn't keep out the interstate. I-70 climbed up and over Berthoud Pass, at more than 11,000 feet in elevation, like it was nothing. I blew by the ski resorts and trophy homes as quickly as I could and was glad to find myself heading down the western slopes toward Grand Junction. Out of the mountains, I was heading directly into the Great Basin, that massive area bounded by the Rockies on one side, and the Sierra Nevada and Cascade mountains on the other. Unlike eastern Colorado and the Front Range, I liked this part of Colorado. It was dry and barren, but it was also clean and pretty. I stopped for gas in the town of Grand Junction, smiling at the surroundings, but anxious for the road ahead.

In Utah I turned off on a small state highway and began following the Colorado river as it ran through canyons and flats, passing one stunning area after another. None of it was formally protected with a wilderness tag, and most was either private or BLM (Bureau of Livestock and Mining) land. After spending a considerable amount of time on the twisty, narrow road, I rolled into Moab, hoping that Providence might smile on me. My friend Stephanie lived here, though I didn't know her address, or her phone number. I hadn't seen her in two and a half years and was hoping that I might just run into her. I ate at a bar where I thought she might have spent time, but the owner could only slightly recollect some one who looked like her. I went over to a natural food store and asked there, but the woman behind the counter was new in town and didn't know her either. I left a note on the wall and hoped Steph might see it. I had to go on. I just didn't have the time.

The sun was setting as I sped through Monument Valley and I was struck both by the freedom of my time, and the constraints of it. I had a week or so, and nothing else. I cherished the time that I had, but it just wasn't enough and I didn't want to go back home when it was over. The sun set and that seemed to help, as I could no longer see the land that I was passing through. Except for the dry air, I could have been anywhere in the US, even back at home. The east entrance to the Grand Canyon was open, but no one was at the entrance booth. No one, it seemed was anywhere. On the forty five minute drive through the park, I didn't pass a single car. At the Village, I found the main campground and located a spot to camp. I opened a warm can of beer for the long (hundred yards) walk back to the pay station to leave a note for Sandy, who was meeting me for the next few days. Swilling the warm Budweiser, and trying not to trip in the darkness, I soon heard a rattle. A familiar car rattle. Sandy's car. I hadn't seen Sandy for a year or so, but remembered distinctly the sound that her car made as it idled. She was sitting looking at the pay station looking for a note from me. She had gotten into the park a few hours ago, and not finding me had been running around making phone calls or otherwise trying to track me down. My cell phone had been off since leaving Indiana. This was going to be Sandy's first backpacking trip and the Grand Canyon is not, perhaps, the ideal place. Huge elevation gains and losses, precarious trail, and bad water. Then again, perhaps it is the perfect spot. For, the Grand Canyon is the most beautiful place in the world. Period.

I put up my tent and popped open another Budweiser while Sandy and I chatted about what had gone on during the past year. Sandy and I were in graduate school together at Illinois and she was now in Utah on a postdoctoral fellowship. I had left Illinois a year before for Indiana and my own fellowship and we compared experiences. I confessed that I had so tired of research academia that I had applied for jobs at a few community colleges in the West, while she confessed her own version of sin. There was a lot to catch up on, but we'd have plenty of time over the next three days. I drank down a few more Budweisers and listened to the coyotes howl in the distance. "How close are they?" Sandy asked. "About thirty feet." I really had no idea, but it sounded about right. This was perfect.

I got Sandy up as early as I thought polite and we went through her gear to make sure she had everything she needed and wasn't carrying too much. Sandy was, as usual, in great shape and as long as she didn't have to carry too much, the elevation changes in the canyon wouldn't bother her too much. With nothing but great weather forecast, we didn't need to bring too much, but had enough pieces of gear in reserve to make sure we both came out alive. We drove over to the backcountry office (a trailer) and got in line to get permits. I hadn't made reservations, as the area of the park we were going to didn't even show up in the park's backcountry map. We waited and waited, and waited some more, as the few people in front of us didn't have reservations either and were desperately trying to put together some form of a permit. The Grand Canyon's permit system is one of the absolute worst that I had ever had to deal with. Massive blocks of the park are marked off. For each block, a certain number of permits are issued. The number of permits issued depends on the type of block. Permits can be reserved several months in advance, so people (like institutional groups) with nothing better to do can get them early, while people like me who prefer to wait until a few weeks before are fairly well closed out.

Sandy left to mail some post cards and get me some coffee, and still I waited. When she left, I was third in line. When she came back, I was third in line. There were two rangers processing the line. The coffee helped to pass the time. Finally, it was our turn. "Sorry, everything is full." I was shocked. The ranger, seeing my disbelief, told me that the particular area had filled in November. "Some college group, or something." Still not believing him, I asked about getting us a permit for the block on the north side of the Colorado. "How are you going to get across the river?" he wanted to know. "Mmm, swim or something." The ranger knew exactly what I was up to, but agreed nonetheless to issue the permit. "Just make sure to get someone with a raft to take you over, and do so before you go down into the canyon." I think the ranger realized that there was something fundamentally wrong when a massive group could monopolize an entire area (very large in extent) and keep two hikers out. What mattered to me was having the permit so that our cars wouldn't get ticketed. If we went down without a permit, our cars (in the evenings) would be a dead give away, and might even bring some sort of search and rescue effort. Our permit came off the printer and the ranger ran through the regulations with me before I signed it and ran away, hoping that the ranger wouldn't change his mind.

Sandy and I drove out to the Desert View parking lot and found only a few tourists milling about, gawking at the awesome spectacle of the Colorado river, flowing 5,000 feet below them through a gorge of religious beauty. We collected our stuff, took the obligatory pictures, and were moving down the trail. The Canyon is a religious experience: Indeed, open any map of the place and look a the names given to some of the areas. Even better, visit the place. The Grand Canyon is one of the few places I've ever been that is simply too large to take in without turning one's head. The scope, the scale, is too immense. In such large, open places, the tedium and constriction of civil life vanishes like a bit of flatulence. My heart rate was up and I was sure my pupils were dilated as we began dropping down the Tanner Trail toward the river, each carrying a gallon jug of water in hand to cache for our last night's campsite. The trail had a bit of slushy snow on it, which we took care in negotiating, but it quickly died out and we were rumbling once again. After the initial drop, the trail ran along a spine, with views out into the forever,and we cached our water here, planning to return in a couple of days.

The Tanner was gentle on the upper stretches, and a bit confusing at times. Part of the confusion had to do with everything that was going on around me. Everything was everywhere. My eyes would wander along the horizon, or a the walls around me, or at the gnarled plants that sprouted up. When Sandy and I came to a rather nasty drop off, I concluded that I should have paid more attention to where we were going.

Feeling a little Gumbylike, we retraced our steps for a quarter of a mile and found where the faint trail had diverged to the right. Had I been paying attention, instead of gawking like some tourist, I would have noticed the large pile of branches that blocked the direction I followed. I preferred the gawking.We began the real descent of the Tanner, but this was nothing to get too worked up about.

Sandy was moving cautiously, placing each foot carefully, and doing well. I'd roam up ahead and then wait for a bit until she got close and waved. Then, more roaming. Half way down, we started running into other hikers and my idea of this being an isolated part of the park were shattered. Not a crowd, mind you, but enough to make things feel a little crowded. Knowing that Sandy would have some company, I loped along and caught up with one after another as they labored under heavy loads. I wondered what they were bringing into the Canyon that so bent their backs. While some seemed to be holding out, others were looking whipped. I shuddered to think what their climb out of the Canyon would be like. I found a large rock and rested in its shade with one of the hikers, chatting for a while, as I waited for Sandy. She ambled up with a smile and joined me on a break, staring down at the Colorado.

The Colorado used to be a murky, muddy red river. It was named for what it looked like. It was now blueish green and filled not with mud, but rather with a fine silt. Upstream of us was the mighty Glen Canyon Damn, and behind it the equally powerful Lake Foul, named, ironcially, after John Wesley Powell. In order to understand the irony, you'll need to read something about Powell and I promise you that you will enjoy reading about this one armed man and what he did during his life. The least important topic, but the best known, was his leadership of the first group to float the length of the Colorado, from its source in Wyoming (the Green) through the Canyon itself. This is his least noteworthy accomplishment. Imagine what else he did. The big Damn changed the character of the river, and the land about it, into what I was now staring at. In return, people in places like Las Vegas and Phoenix got some electricity and enough water to have golf courses and emerald lawns in the middle of the desert. It brought power for companies to expand and grow, bringing, hopefully, jobs and economic development. And pollution. And, most importantly, an end to the wild nature of one of the few remaining pockets of wilderness left in the continental US, and a submerging of one of the most unique places in the world. Whether the benefits of Glen Canyon outweigh everything else is a matter of perspective. Work it out for yourself.

I reached the river a few hours later, though separated from Sandy. I passed a group of older men resting in the shade, with massive Dana Designs Teraplane packs sitting next to them. They were beat and certainly didn't need my smiling face to annoy them. I found a nice, shady spot by the river and grabbed some silty water to drink. There was no other option in the area and when you have no options there is no reason to grumble. My iodine was working on the water when the only two hikers with small packs rolled up to meet a boat that had just arrived. It turned out that they were members of a scientific group that was measuring the numbers of various fish in the Colorado. It shouldn't be a surprise that the Damns were effecting the fish population as well. They offered me a variety of things, but I was quite happy with what I had and tried to get them to tell me more about their experiments.

Unfortunately, it turned out that they were just the "help", rather than the senior scientists who had more information beyond just what they were doing. I waved as they pulled away and wondered where Sandy was. I walked around looking for her and eventually located her by shouting. She had gotten bad information about the direction I had gone from the old men and was wandering about somewhere else looking for me. We sat in the brush for a while drinking water and resting, before starting the run down the Beamer trail, which would eventually end at the junction of the Colorado with the Little Colorado. We wouldn't get there today, but I wanted to get over and around the first few obstacles and down to a flat area that would make for good camping.

The sun was beginning to dip and bit, as it frequently does in canyons whose walls are 5,000 feet above you. Sandy was moving fine but had a little difficulty on some of the more narrow segments of trail. While nothing for me to worry over, for her they represented something dangerous. Just as I get spooked on things that friends consider easy, so Sandy was spooked at times. Never did it stop her. It just slowed her into caution. We passed through the obstacles and then down onto a long stretch of sandy beach that ran out for a mile or two. On the other end there would be more obstacles, and I could see them, but we didn't have to worry about them until tomorrow.

It took me a while to find a campsite that was just right (I'm very particular about this) and set up my tarp for Sandy. On such perfect night, there was no chance that I would sleep under some sort of roof, even if it was made out of silnylon. I wanted to see the stars and the outlines of the cliffs above and the meandering water. I wanted it all. We cooked dinner on my alcohol stove and talked for a while, although for not much past sunset. Sandy was tired, but had never complained. Not once. No sign of weakness or trouble. Just ordinary caution. I thought back to some of my early backpacking experiences for some comparative mirth.

I sat and read for a while, sipping on hot tea laced with overproof rum, but eventually gave up and stared up at the stars to think for a while. I liked looking at the stars when I was out in the backcountry, but rarely did so when I was at home. They just didn't seem to have the same kind of meaning if I wasn't sleeping on the ground, out under them. Memories of the PCT floated by in my head as I drained the last of the tea-rum mixture and I grew a bit melancholy. Compared to then, compared to now, I saw little reason or desirability in my life back in Bloomington. Definitely comfortable. Definitely not worthwhile. I could hear Sandy breathing gently close by and wished she was awake, but I knew that she had been sleeping for two hours now and needed her rest. I looked at the stars again and drew some more hope from their cold, million year old light. The stars had made it so far. I could make it a few more weeks until the summer time was here.

Morning breaks late when you are in a canyon whose walls jump four thousand feet up. From my sleeping bag I could see that Sandy was still dozing in the cool shadows that fell over our campsite. I munched on some breakfast and rustled around a bit, which was all she needed for an alarm clock. In twenty minutes we were hiking with small loads of food and water, on our way to the junction of the Little Colorado with the Colorado following the Beamer trail. After crossing the long beach we started on the climb up and onto the face of the walls, following a cairned route at times rather than a built trail. From an overlook, we could spy the rapids next to which we slept, far down the beach, still in the shade.

The Beamer wasn't a superhighway. It required you to remember where you were going and to keep an eye out for cairns. This was fun hiking rather than monotonous walking and the challenge of the Beamer was just right. The air was still cool, but the sun was warm on my skin and I couldn't imagine wanting to be anywhere other than where I was. This feeling is what drives me into the outdoors, into that simpler place. It isn't an escape or a re-vitalizing experience. Rather, it is simply a better way to live. Others find it in other places or activities or mindsets. But, the goal is the same.

Because the Beamer was routed along the walls of the canyon, we had to wind in and out of each recession in the walls. These amphitheaters, for this what they truly are, didn't show up on my terrible National Geographic map. Rather, the Beamer was show as a nice straight line all the way to the Little Colorado. Moving in and out of the amphitheaters took time, but it was time well spent. All time here was well spent. I thought about a line from a movie, "This is your life. It is ending one minute at a time." We don't like to think about this back in civil society, for most of us lead lives that are unsatisfying from minute to minute and from day to day. Pondering wasted minutes, or minutes spent pursuing worthless objectives, is not a pleasant thought and so we close our minds to our dreary lives. Here, now, I could think of it because each minute was joy. Each minute was worth something, to me at least.

We had been on the Beamer for several hours before I spied what had to be the junction, although I could not yet see the Little Colorado: A massive cliff and a big turn in the Colorado told me so. Sandy and I had become separated as we each moved along the Beamer at our own pace and according to our own inclination, exactly as two people should hike together. Or not. Depends on your inclination. The Beamer had become more broad and Sandy was gaining experience rapidly and didn't need me around to get along. However, when the Little Colorado came into view, with its turquoise waters flowing into the green Colorado, I stopped and waited, standing the sun on a bit of exposed trail. Sandy arrived ten minutes later, looking tired. I pointed out the river junction, just a mile or so away. We split up again and I was at the beach, sitting in front of the preternatural water of the Little Colorado twenty minutes later.

There was something very wrong with the water from this stream. The only times I have seen water that was even close to the same color was high in the mountains in glacially fed streams. There wasn't a glacier within a two thousand mile radius of here. I was out of water and was rather parched upon arrival, but left a large arrow for Sandy to follow to find a spot in the shade by the banks, before grabbing my water bag and heading to the river to get something to drink. The rocks told me what was wrong with the Little Colorado. A sheen of white was cast upon the rocks sticking up out of the river or along its banks. A sheen that comes from salt and dissolved minerals, rather than dissolved rock in a glacial stream. I sampled some of the water and found it to be drinkable, but not pleasant, at least for now. We needed water and the worst that would happen would be some bowel irritation. I filled my bag and treated it without iodine, hoping the iodine would improve the flavor, and then retreated to the comfort of a river side thicket to rest. Sandy was along shortly and proclaimed her happiness in arriving, finally. The distance given by the Park Service was consistent with my map. It wasn't consistent with reality and the trek here had taken an hour or two longer than I had expected. It didn't matter. It was time well spent. There were a few boat people milling about like refugees. Some walked around the water, others tried to swim. Some sat about and ate. They seemed lost to me, but it may just have been the sun beating down on their exposed, pale skin.

Sandy and I stayed in the shade for ninety minutes talking and napping and drinking some of the strong water from the Little Colorado. Reading through history, or travel narratives, one frequently encounters the idea of "sweet water." This concept cannot possibly be grasped by words on a page, for the notion of sweet just doesn't translate: You need to drink water like what we got from the Colorado in order to understand how sweet modifies water. The boat people were packing up as their handlers had declared that it was time to move on. Floating down the river seemed like a pleasant idea to me, but I was happy that Sandy and I were not among the boat people at this moment. They were being taken somewhere. We simply were.

The trek back along the Beamer was as fun as before, except for when we got a bit lost and ended up scrambling a little along the side of rocky hill. It wasn't something I noticed, anymore, as being difficult or scary. Looking back, I could see myself in the past as Sandy struggled with footing on the slope and with the prospect of the river several hundred feet below. I walked back to her to help her with the last few yards of the traverse and we quickly found the trail once again. I suggested that we take a break and rest for a while. "No, not until we are down." Now, I was hearing the past as well and understood not her words, but rather the meaning behind them. On we went.

By the time we reached the beach once again the sun had gone behind the walls of the canyon and both of us were hungry and a bit tired. From our camp to the Little Colorado had been, approximately, nine miles. An 18 mile day along the Beamer and back was a bit of a grunt, but one with rather special rewards. Some boat people had landed and camped on the beach, but far from where we were staying. I wondered if they had bother with permits, or because they were boat people (and hence generated revenue), they didn't have to deal with such things. The boat people were surprised to see us, as they had spotted us resting at the junction and left at about the same time we had. It seems that boat people don't walk any more than ATV riders do. They were equally surprising when we told them that we had been drinking the water from the Little Colorado. They laughed and giggled as they proclaimed how much fun our guts were going to have that night. I smiled and nodded, not wanting to spoil there fun. They did give us some filtered Colorado water, which I drank more out of courtesy than need or desire.

Night fell on the inner canyon as we ate dinner and talked. The boat people were having fun with the massive spot lights that they were hauling. I suppose the lights would be used if they had to float down the river at night. But, in practice they were being used as playthings. Shine it here. Shine it there. Look, it really lights up the night well! Not mere flashlights, we have big powerful things here that could light up a block in Las Vegas! I felt more pity than anything else, at least after my revulsion died down. The boat people played with their lights for thirty minutes before settling down and leaving the Canyon in peace once again. Sandy turned in and left me to the stars and my Earl Grey - Rum mixture, spiced with Edward Abbey from time to time. I'd read for a while and then turn off my light (which is the size of a nickel) and star up at the stars from my sleeping bag. Stars, then Abbey, then stars again. My head began to feel light as my mug slowly drained away and finding shooting stars and satellites became more challenging. Stars, then Abbey, then stars again. Stars always.

When Sandy and I first talked about this trip a month back, I didn't want her to have to hike from river to top in a single push and so we had planned a short day today. Just back up to where we had cached our water. However, Sandy was more than strong enough to get out in day and we talked about this option as we moved along the Beamer in the early morning shade toward the Tanner. There were some boat people camped on the other side of the river and we watched as one urinated directly into the water from the bank. While I loved being in the canyon, and the prospect of a night where we cached water was invigorating, we decided that, all things considered, it might be best to hike all the way out if we had the time. This would give us some downtime in Tusayan, just south of the park, before I left for Tucson and a friend's wedding.

I waved goodbye to the boat people and we set out on the climb back up the Tanner. Hiking uphill is easy if you have plenty of time, though it helps if you are in shape. Sandy was in great shape and moved along without any visible signs of difficulty. We got into our own rhythms and separated for a time, but came back together near the point where I lost the trail a few days ago. A group of two dozen college students were standing about wondering which direction to go when our arrival sealed their decision. These two dozen students were all on one permit, I assumed, despite regulations against such things. I didn't particularly care for the regulations, but I did wish that they applied equally to all. It was barely one o'clock in the afternoon when Sandy and I reached our water cache on a spectacular ridgeline.

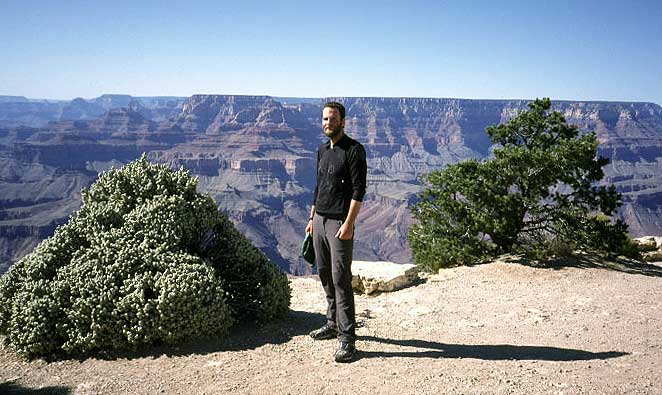

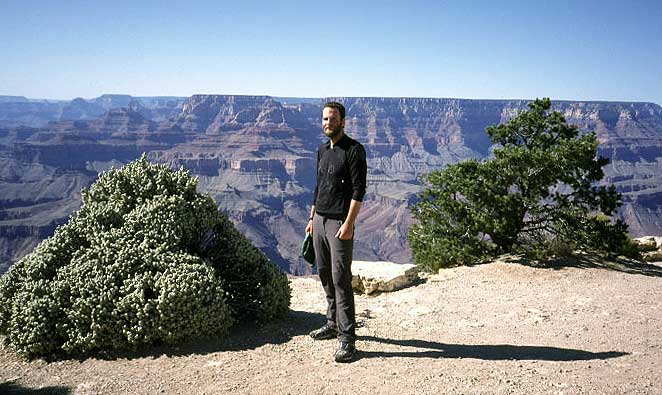

I sat in the shade of a gnarled tree for a while contemplating the Canyon. As much as I loathed the process of getting a permit, it really was worth it. In fact, I'd move to Flagstaff for the sole purpose of being close to the Canyon and being able to explore it at my leisure, instead of once a year for a few days only. Sandy came and sat next to me for a while. We'd murmur words occasionally, but silence seemed the appropriate approach. Sort of like being in a church. "Ready?" "Yes." And we were off, climbing back up to the rim. Back through the snow and back into civil society. The Desert View parking lot was filled with cars and gawkers, and two large buses with Indiana University logos on the side of them. We didn't even bother to change out of our salt stained clothes, and stopped only long enough to take a few, final pictures before driving back to the Village and eventually to Tusayan. A small motel advertised "Clean" rooms (so, you know it will be cheap) and it was just down the street from another joint boasting of its T-bone steaks. Nothing more was needed.