Searching for Mount Hickman

July 13, 2002

I drove down the gravel and dirt road slowly, thinking about everything that I leaving behind and everything that was in front of me. The commune where Stephanie lived, on the Illinois river (located, oddly enough, in southern Oregon), had been a wonderful place to spend the last few days and I thought about how nice it would have been to spend another month or two there. Or a year or two. I wanted to stay, but could not. I was wanted in Vancouver. To take my mind off Oregon, I called Mike on my cell phone to let him know I was on my way. Mark was cooking tonight, and that was not to be missed. I sped through Grants Pass and onto I-5, my home for the next few hours, pushing the gas pedal down toward the floor and racing into the future.

We were going after Mount Hickman this summer, hoping to reach that named, yet unclimbed, peak that we had spotted on the other side of Mess Creek. Into Arctic Lake, down and across the possibly unfordable Mess Creek, then up and into the snow and ice. After recovering a food drop, we'd climb and then traverse through to Yehiniko Lake via the Scud glacier and get picked up Doug. It was a simple plan. I wanted to focus on it, but other things kept getting in the way. I wondered where my friends from the Appalachian Trail happened to be. Where were the Trees and Daddymention and Paul Revere? What was Virginia like? As soon as I pushed thoughts of the verdant Appalachian Trail from my head, they were filled with images of the last few days in Cave Junction with Stephanie and Melissa and splashing about in the Illinois during the hot nights. Images that filled me with happiness. Images that made me melancholy at the thought that they were in the past and not in the future. I stopped to get gas and take my mind off of them.

I pushed through the Olympia-Tacoma-Seattle megaplex, doing my best imitation of Mario Andretti, and hoping that the Highway Patrol would be sensible enough not to pull anyone over and create more of a traffic jam. Weaving in and out and using all four lanes of traffic demanded some attention and, for the moment, I forgot about Oregon. Everett, Mount Vernon, Bellingham. Finally the border.

"So, where exactly are you climbing?" the border agent asked me.

"Mount Hickman. It is up by the Stikhine," I replied, knowing full well that he could place it.

"Where is that?" the agent wanted to know.

"Near Dease Lake," I replied.

"Where?"

"Near the Panhandle, south of the Yukon border," I offered.

The agent eventually wished me luck and waved me through and I pushed hard for Vancouver and Mike and John's new place. My car had been stolen in broad daylight, on a Sunday afternoon, from infront of John's old apartment and I was glad to hear that there new place was in a better neighborhood. I found the house and knocked on the door. John down from Mark's apartment on the second floor and led me upstairs. Dinner was just finished, but they had a plate all ready and waiting for me. Mark is something of a chef, and the dinner, under any circumstances, would have been divine. As it was, I had spent the last two months backpacking or traveling and my palate, used to the dull flavors of ramen noodles and Lipton's Rice and Sauce, jumped up at the presence of seasonings other than salt and immitation butter flavor.

After dinner we unpacked my car and had a few beers before calling it a night. I was tired, having gotten only a few hours of sleep the night before on the gazebo overlooking the Illinois, but I couldn't still my mind enough for sleep to come. I was worried about Hickman and what we would face, and I was longing for Oregon. As I thought about the snow and rock and glacier ahead, and the ninety pound pack that would come along for the ride, images of sitting under a tree in Oregon flitted through my head. Falling in a crevasse, or playing in the river. I hadn't even left Vancouver, and I was already questioning my reasoning for coming on the trip.

There was much to do, and only a day to do it in. I had brought a lot of food with me across from Indiana, and this would form the bulk of our dinners. I had cooked and dehydrated for ten solid days in Indiana, inbetween leaving the Appalachian Trail, moving from Illinois, and setting out for the west coast, and was glad that I had done so. No freeze dried meals for us. But, I needed a bunch of lunch food and other supplies. Mike and John, in true fashion, hadn't bought anything yet. We spent an hour collecting food at a Safeway, and then another hour repackaging it. We were going to try a food drop from Doug's plane to try to ease our burden. We were carrying enough food to get in place to climb Hickman, but no more. Doug would fly over and an assistant would hurl a box and a bucket out of the plane. In this way, we would be resupplied with food and fuel for the rest of the trip to Yehiniko. The food taken care of, we had to deal with the special gear we needed for the glaciers and the climbing.

John spread out a large tarp on the back porch and we began to fill it with bits of iron, aluminum, and nylon. Mike brought out an entire rack of rock protection. One rope. A second rope. Pickets, ice screws, deadmen. Slings, ascenders, ATCs. As no one had been in the area before, we had only a vague notion of what we really needed, and what we did know had come from a study of maps and from what we saw last summer. At last it was declared enough and, having split up the other communal gear, we set about packing our pigs to the fullest. I came in around 90 lbs. John had around 80. Mike, carrying a significant amount of camera gear, was over a hundred.

We spent a final night looking over maps and pictures from the summer before, and I tried to reassure myself that everything was going to go well. I tired, and failed, to forget about Oregon and the Illinois. I tried to focus on the future. I failed in all tasks. A few too many beers helped me fall into a dreamless, dull sleep.

We spent the next day and a half driving north in my overloaded Camry, jammed with gear. The rain forest aspect of Vancouver faded as we drove into the dry interior, resembling southern Oregon in many respects, and then into the plains around Prince George, which bears a striking similarity to Iowa. We spent the night in a motel run by a man whose son had just got back from a climb of Mount Logan, the highest peak in Canada. He had flown in, skied for a day, and then sat in his tent for five weeks as storm after storm pounded the area. This seemed to be most people's experience with a climb of Logan. We drove up the Cassiar Connector, named after a town that no longer existed and in which John had grown up. "Improved" was the classification of the road, and this meant that it was something slightly better than gravel, but not by much: After making the same drive last summer, my Camry's exhaust system had looked like it had been shot repeatedly with a fowling piece. Rain, rain, and more rain poured down upon us, and I took some comfort in the ridiculous idea that if it was raining now, it wouldn't be raining later. After a few hundred kilometers on the Cassiar, we finally rolled into the Tatogga Lake Resort, where Doug was based. The resort consisted of a gas pump, a restaurant, and several ratty cabins which provided only some relief from the mosquitoes, but in return we had to fight the mice. Last summer, mice had eaten two dozen cheese biscuits, containing more than a pound of cheddar, that I had baked up before hand.

The rain kept coming down, sometimes in sheets and other times as a fine mist. Even the powerful northern breed of mosquitoes had difficulty navigating in the rain, which meant that we could sit on the porch for a while without smothering ourselves in DEET. There was a squad of BC park rangers that were flying into Spatsizi, to the east the Hickman area, for a month long patrol. Oddly enough, a third of them consisted of very attractive, very fit young woman, which gave me something to think about: The BC Parks hiring practice seemed to coincide with the hiring practice of the US Park Service. Perhaps I should drop the whole math thing and go into the Park Service instead. After getting our food secured from the mice, and talking with Doug for a bit, I drank a few beers and tried to steady my nerves for the day ahead. We might be able to get out tomorrow morning, thought Doug. Or, we might have to sit for another day until the weather cleared. Or another day. Or a week.

The morning weather was not pleasant at all. While the rain was only light, there was a very thick fog sitting over the lake and Doug wasn't about to fly under such conditions. We sat in the restaurant eating breakfast and drinking coffee and making eyes with the park rangers, who mostly just ignored us. Waiting and waiting and waiting. In the afternoon, Doug declared the weather good enough to fly and took the rangers out to Spatsizi. After refueling, upon his return, we loaded up the plane and began the short taxi out to one end of the lake.

Having flown in the float plane the summer before, I was better prepared for what was to come. Sitting up front with Doug, with Mike and John smashed into the back, I had the best seat in the house. Starting slowly at first, Doug opened the throttle and we slowly moved forward. We were near the plane's load limit in weight and speed came slowly. When it felt like we were moving at about 30 miles an hour (surely, we were faster than that!), the lake dropped away in inches and we were airborn. The flight to Arctic Lake is about as far as Doug could take us (about an hour), with gear, land, take off again, and get back. Last summer, Arctic Lake was about half covered in ice and had presented something of challenge to the experienced pilot. This summer, after passing by the incomparable Spectrum Range, we found Arctic Lake to be thawed and wide open. Doug circled a few times, losing elevation slowly, before almost stopping the engines and gliding in for a smooth landing. We taxied to the southern end of the lake and were off.

After getting the plane tied to the rocky shore, we ran through the plans with Doug once again and checked to make sure we had the right phone number. As with last summer, we were carrying a satellite phone for emergencies. We had rented a new model this time about. The instruction book was sitting back in Vancouver. After a few final parting words, Doug fired up the plane, taxied, and took off with much less effort than before. We were alone. Completely, and entirely alone. With almost complete certainty, there was no one within fifty miles of us. In fact, the closest people to us were most likely the folks who ran Tatogga Lake Resort. Doug had not brought anyone else into the area, and Doug was the closest float pilot. Telegraph Creek, in the north, was just too far. No rangers would come for us. There would be no shelters in which to hide from the rain that was now falling. Illini Peak, which we had named last summer, sat above us and the long, broad Arctic Plateau stretched out to the north and south. Last summer we had gone north and eventually ended up in Mount Edziza Provincial Park, which had a cairned route through it. Now, we were going south and there was nothing except for wilderness. Occasionally prospectors came into the Arctic Plateau, but once we dropped down into the Mess Creek, we would be in virgin land. The first people. The land was too remote and too difficult to get into, the commitment level too high. There were easier places for the First Nations to live, and hunters could find similar game in more comfortable areas. No, we would be the first.

This far north, at this time of the year, the sun barely sets. There is usable light until around midnight, and then it sort of fades to a dark purple, before the sun comes up once again. The rain ceased and we set off south to get a little closer to the drop off before Mess Creek. The plateau provides easy, if mushy, walking and even with the big packs on our backs, we were able to rumble along just fine. Because there is nothing to knock the wind down, the mosquitoes had little chance to feed upon us during the two hours we hiked along. Finding a relatively dry spot to camp, we pitched our tent and set camp. This was easy, I thought, just like last summer. The plateau was deceiving, however, as we knew that in another few kilometers we would be at its edge and have to face a bushwhack down to Mess Creek. We didn't even know if we could ford Mess Creek.

We had only a vague notion, gleaned from hours spent in front of the maps, about how to get out of Mess Creek. Once in the mountains on the other side, what would the glaciers be like? Would the weather clear. I was powerless at this point, having given up all control when I stepped on the plane a few hours ago. The land was in control now, and I had to accept that. The three of us could do the best we could, but the land wouldn't care at all. There were no trails to help guide us, no books that described a route. A set of maps, lots of gear, a GPS, with several back up compasses, and determination might see us through. Or, it might not. The land might kill us instead, and the wolves and grizzlies pick our bones over before winter set in and covered all trace of our existence.

Today we were going to face our first major obstacle: The ford of Mess creek. Mess creek drained a rather massive area and was glacial fed. Little information on it could be had and there was no way around it, no bridge, no cables. After breakfast and tea and striking camp, we traversed a bit more of Arctic Plateau and then moved over toward the edge to get a view of Mess.

From my perspective, it didn't look too bad. Mess was heavily braided in places, which hopefully meant that each individual ford wouldn't be too difficult. There was a nice system of banks on either side so we could get into the water easily. Unfortunately, there was no easy way down. The coastal rain forest was built up thick and nasty almost all the way up to the plateau. The drop in elevation was serious, as was the grade, and as we moved lower the bugs were sure to come out in force. The DEET came out and I asked Mike and John how we should proceed. "Take the best way down you can." Not much help, but rather true. We spotted the expected valley on the other side, running up toward a glacier. This would be our route tomorrow, assuming we got across Mess today.

The descent, straight down the hillside, was steep almost everywhere. The thick brush choked our progress and acted as a, sometimes, helpful brake against gravity. I postholed, repeatedly, in rotten logs and patches of moss. I thrashed through Devils Club and came close to breaking my leg on several occasions as a leg got stuck between non-rotten logs and my body began to topple over. The bugs came out in force, attacking with a fury that only the North can provide. I lost sight of Mike and John quickly, which wasn't saying much as visibility was only four or five feet for the most part. Occasionally I would hear sounds of their cursing or of John's ice axe cutting out some Devils Club. But, mostly I struggled on my own to push down through the brush. I fell, I swore, I lost blood. I took shots in the face from trees and bushes and kicked over the Devils Club whenever balance allowed. After two and a half hours of torture, I finally found that the ground was once more flat and saw Mike and John once again. We had only to push through a few small thickets, and out we popped on the banks of Mess creek.

My thirst was intense and, after tossing down the pig, I immediately went over to the silty water for a deep drink. The glacial milk was surprisingly sweet and not unpleasant at all. I drank and swatted mosquitoes, and drank some more. My hands, neck, and face were the only bits of skin exposed to them, although they tried mightily to bite through the various bits of clothing. A fun game was to sit still for a few moments, and then quickly pat my head and see how many dead mosquitoes would come off. A kill of five or six per swat wasn't much. A dozen or more was more common. Although we were all happy to be done with the green hell and kill mosquitoes, Mess was now in front of us and needed to be dealt with. Everything seemed positive, as the water wasn't too fast, and John had taken some initial soundings and found that it wouldn't be a swim. I asked them what the best way to ford such a thing was.

"Wide stance, always be in balance, never lift your feet. Be a beast."

And so, with that, we waded out in to the water one at a time.

To my delighted surprise, the ford was easy. Shuffling my feet, rather than lifting them, kept me on balance and helped me avoid rocks and I got to the other bank in only a minute or two, wet from the lower thigh down, but quite safe. We took another break on the other side to wring out our socks. Besides needed to do this, we now faced another green hell bushwhack to get to the glacial valley we had spotted from up on Arctic Plateau.

The bush thrashed us once again. Pushing, struggling, cursing, whacking, whatever we could we tried. At least it was flat. A machete would have been of little use here, as the bush was thick enough to prevent one from getting a good swing. A chainsaw would have been more appropriate, but it would have run out of gas after only a few meters progress. The bush was that bad. The bulky, oddly shaped pigs on our backs didn't help matters at all. Finally we found a short clearing where we could climb up and out of the green hill and traverse along an open slope. Being in the open air seemed a paradise compared to what was below us. We could even spot the end of the glacier that would, hopefully, provide us with a highway up into the mountains. Mike dubbed the run off the "Snout of Mess" creek, and we were all pretty happy when we finally reached it and declared the day over. I was exhausted, but cheered a bit when John said that todays hike would have broken 90% of the hikers he knew. I tried to figure out if I was broken or not, but as I could still help get the tent up decided I wasn't fully broken.

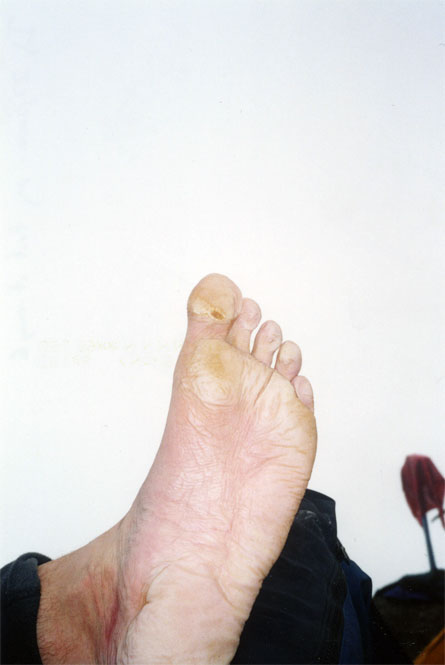

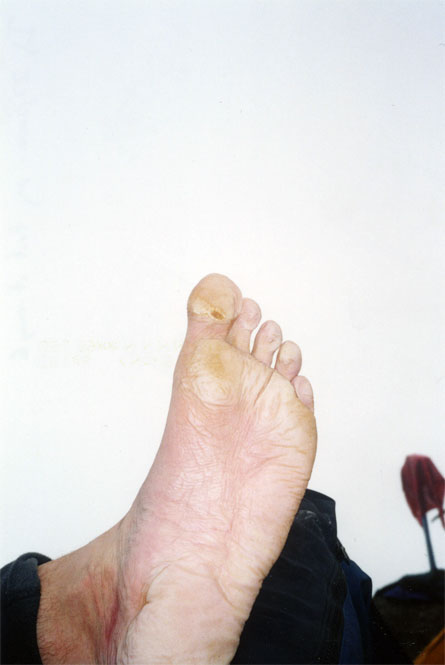

We gathered a massive amount of downed wood with which to make a large fire for the night. I was feeling strong, healthy, and unstoppable. With the exception of numerous scratches and scrapes and a blister on my right foot, I healthy and alive and fed off the Land. The fire brought some warmth to us, and allowed us to partially dry out from the ford. Since no one came here, ever, and because of the unique nature of the environment, our traces would be erased by the winter. Indeed, the plants we hacked down in our bushwhacking were already being replaced by the rain forest. There was so much life here that it almost became cheap.

After dinner my exhilaration wore off, however,

and was replaced by fear. We have over a thousand meter gain to get up the moraine and glacier and onto the snowfield that should take us to Hickman. I hadn't spent much time on glaciers before and was worried about small things, like falling into a crevasse. Or, getting taken out by rock fall. Or, running into some problem that I didn't know about right now. Fear of the unknown was running high in me at the moment, and I suspected it wouldn't end until I saw Doug gliding in to get us at Yehiniko. I wasn't afraid of the physical effort. I was afraid of what was lurking in the shadows of my future; what was there, waiting, but about which I could not possibly know.

We slept late and sat around drinking tea in the morning sun, safe from the mosquitoes thanks to a pleasant breeze blowing down the valley from the heights above. We finally loaded the pigs and took the first steps toward the unknown that I had feared so much the night before. And now. However, moving forward toward whatever It was seemed to calm me. We moved past the Snout of Mess, which barreled out from a tunnel under the end of the glacier, and started up a rocky moraine. Ice was just below the rocks, and at times I slipped about as we gained elevation. The moraine ran and ran and kept on running, which kept us off the glacier and provided for numerous places to stop and gawk and rest. According to the GPS, we gained 570 meters on the rock and ice before it came time to take to the glacier itself. This, however, called for a long lunch in the sun.

The lower end of the glacier was fairly broken up with crevasses, but started to even out as we moved up the moraine and now looked only moderately terrifying to me. John and Mike didn't seem to notice anything odd, from which I drew some reassurance. After lunching for forty minutes, we roped up and were preparing to set out when something drew our collective eye. The moraine split the glacier in two, and on the left half, we saw two things running toward us over the snow and ice. Cameras came out. "What are otters doing out here?" Mike seemed to ask. As the shapes drew close, it became clear what they were. One wolverine was chasing another wolverine across the glacier. They came tearing along and in their chase were oblivious to our presence. They crossed ten meters in front of us and kept going on the other side of the moraine, before scrambling up into the hills on the other side. The three of us looked at each other, as if to verify that we had all seen the same thing and were not being taunted by some sort of illusion. Wolverines are very rarely seen in the wild and wolverine researchers can spend a career and never see them in their natural environment.

The cameras got repacked and we were, once again, getting ready to set out when, once again, something caught our eye. One of the wolverines was coming back. Limping this time, and moving slower, it was returning from whence it came, and heading directly for us. The moraine was slightly elevated and the wolverine still had no clue that we were there. Mike and John brought out the cameras to get some pictures, while to me was left our collective defense. I didn't really want to think about what might happen if the wolverine became startled and was close enough to us to want to fight. I put my jumbo-sized bear spray in my pocket where I could get to it, my ice axe within reach, and grabbed two large rocks. It drew closer and closer and I heard the shutters of the cameras going off. Closer and closer. It halted five meters from us, unsure of what was ahead. It knew something was on the moraine that shouldn't be there, but couldn't place us. Almost certainly we were the first humans it had smelled. It paused, and then fled down the glacier, across the moraine below us, and then up and along the other half of the glacier, now in full sprint. Again, we looked at each other.

We set out on the glacier after getting packed for the third time. Although I fell a couple of times when my feet got tangled up, mostly the climb up the glacier was uneventful. The crevasses ranged from easy end runs to full on leaps. Fortunately, Mike was in front and hence had to leap first before I came to the jump off.

"Keep your Mo forward," Mike advised.

At each jump, I'd take a few running steps and then leap forward over the crack in the glacier, my crampons providing enough grip on the other side for traction, and my momentum doing the rest. Mess Valley began to recede into the distance as we gained elevation on the glacier, its greenery the last we'd see for a while. As we neared the top of the sloping glacier, the crevasses began to be filled in with snow, which was a comfort and a dread. As long as the snow was thick enough, we'd never know of their presence and could walk comfortably. But, if the snow was thin enough to collapse, one of us, most likely Mike, would go for a fall.

Mike moved forward slowly, probing with his ice axe, and trying to pick out the least dangerous route. Occasionally, he'd make an unlucky choice and put a leg through a snow bridge. I hit the glacier once, but mostly Mike could retrieve his leg without too much effort. He seemed very calm about it all.

We took a rest break on a safe looking patch of snow, just below the top, and rested. Physically, the work wasn't overly demanding. The heavy pack made forward progress difficult, but it was only difficult. Now that the crevasses were gone and the weather was holding, it was a joy to be up here. Now, we were only hiking and the future, at least the near future, didn't seem so terrifying. Our maps showed a nice, big, flat snow field waiting above us, and from there a good run, with a couple of minor climbs, would get us to Hickman and our food drop.

The snow field above us proved to be as gentle as expected, although we only moved along it long enough to find a reasonable campsite on some rocks on its edge. Given our late start and slow progress on the lower end of the glacier, we hadn't moved very far as the crow flies. However, the open expanses of white snow and blue ice, with black mountains dropped in snow on the boundaries, were too much to pass up. A campsite like this belongs on the cover of National Geographic. The temperature began to drop and I had to put on all my clothes to try to stay warm. A month ago I was sweating in the humidity of southern Appalachia. Now, I was freezing, despite numerous layers. The cold compounded the fear that had been struck me during the past few evenings, even though I knew tomorrow wouldn't be very difficult. We had the snowfield to traverse into a cirque, and that would take up an entire day. It was only after that traverse that things would get difficult. To Hickman, up Hickman, find our food, get to the Scud, get to Yehiniko. It seemed very far away, and thoughts of sitting under a tree in Oregon seemed much more appealing, right now, than freezing in the cold wind of a northern July.

I awoke terrified. The notion of being in uncharted land sounded appealing when I was at home, warm, sitting on a futon, drinking a beer. Could we get through to Hickman? What about our food drop? Yehiniko seemed very, very far away from this patch of rock above the snow and ice. The feeling persisted through breakfast and throughout the day.

We continued to traverse along the snow field we had encountered yesterday. I kept quiet about my fears, partly hoping that they would go away, but also not wanting to admit that I was spooked, even on this easy ground. Roped together, we moved toward the large cirque that, tomorrow, we'd climb to get near Hickman and our food for the future. The snowfield degenerated into slushy, watery ice, but there were no crevasses and the small pools of water that formed made for excellent drinking. We stopped early, at the edge of the cirque, the last reasonable campsite before the climb up and off of the snowfield. Complete with running water and awesome views of the local peaks, it made for an excellent campsite.

My dour mood continued through the early evening as thoughts of the immediate future clouded what should have been an enjoyable day. Despite being camped in, perhaps, the most scenic spot I'd ever been to, I couldn't relax and enjoy myself. After a month on the AT, lounging in the sun, rambling up and over the sweet smelling forests of southern Appalachia, I was strong and fit and could handle the physical aspect of this trip. But, the mental ease that the AT had instilled in me was the worst possible preparation for this sort of thing.

After dinner I strolled about the immediate area of the campsite, hoping to pull my thoughts together, for I knew that if I continued in such a mind set, an eruption or breakdown would occur within a few days; A mind wound too tightly will fail quickly. I sat for a while and watched Mike and John take photographs, acting as natural as they do in Vancouver. No worries, it seemed. Perhaps when I get through this, I will be able to summon the same kind of nonchalance to my side. Perhaps not. I hoped for a better tomorrow, when my mind might be able to relax, when I might be able to fully enjoy my time out here, rather than simply being awed by the surroundings, and scared by the future.

I was feeling better in the morning and was actually ready to face what loomed above us. We set out from our cirque camp under partly cloudy skies and moved along the rocky boundary of the snow and ice field we had traversed yesterday. John had me lead the way along the rocks and onto the snow, where I dutifully kicked steps into the snow, switchbacking up toward...whatever it was.

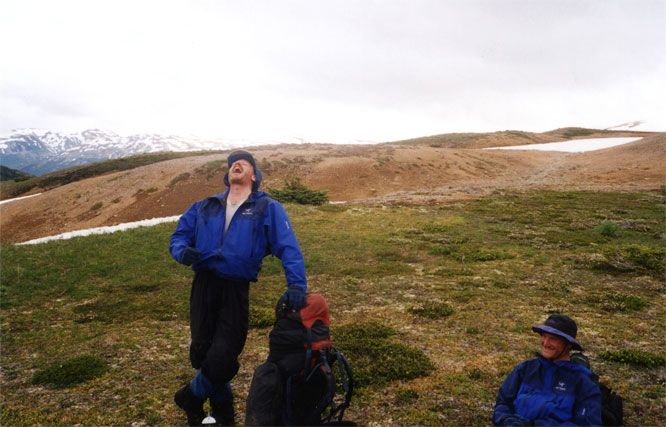

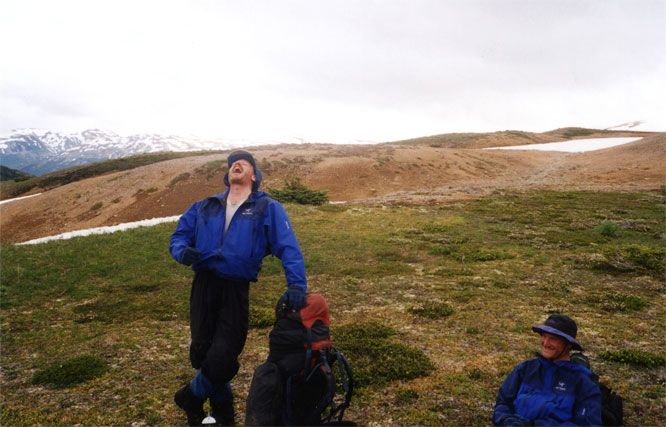

We rested, more for my benefit, on a rock outcropping in the middle of the frozen sea around us. Breaking out some gear, we roped up as the snow began to degenerate and there were numerous obstacles to be run around. Or fallen into. John led out, heroically kicking steps and placing bits of protection as we went. Mike, in the rear, removed the protection and we moved in a more or less efficient manner up the snow slope, dodging crevasses and bergschrunds as went. I was surprised when we reached the top, partly because the thick fog that had settled onto us blended with the white of the snow to produce something like a camouflage for the land. Tired, we plopped down onto the snow to try to wait out the fog and get a clear view of the land around us. Fortunately, our patience was rewarded and the fog drifted off, revealing the peaks around us and the land in front of us.

Having gotten up, we now had the easy part of the day in front of us: A nice stroll down a solid snow field, bend left, go over a minor col, and we be at the snow field that held our food drop and Mount Hickman. The weather was even getting pleasant, and we were all in good moods as we realized that at least the approach to Hickman was ours. Nothing could stop us.

As we moved down the sloping snow field, we began noticing a few crevasses. And then more. Still on rope, Mike began moving more and more cautiously. I stepped where he stepped, jumped where he jumped, moved as he moved. Around one. Around another. I watched Mike probe and then jump a potential crevasse and proceeded to do the same. Except that where he floated across, when I set foot on his jump-off point, I fell through. I yelped out something that sounded like, "Falling!". I found myself into my armpits, one leg floating free in the air, one curled up underneath me. My pack had kept me from going all the way in. I looked back and saw John face down in snow in full arrest. Mike in front was the same. The rope wasn't yet taught. I wasn't falling. After asking what to do, I began to gently try to get myself out. The big pack didn't help, but I eventually managed to extricate myself and flop over on the comfortable, safe snow. Looking down into the hole I had left, I could see that I would not have fallen very far. No, not far at all. Right into a nice wedge inbetween two blocks of ice. I was glad my glacier glasses were on, for I thought I might cry soon.

We gathered together and talked about it. Mike didn't like the look of things, and I certainly didn't either. We couldn't go forward, so we went sideways and hoped for the best. Moving along the snow wasn't so bad, but when we started moving near seracs and other hazards, the strain began to tell on all of us. Getting some perspective, we found that there was no way we could get to the Hickman snowfield; the snowfield was just too busted up. After a brief consulation with the map, we decided to head to a spit of land to see if we could get down and around. This became known as SOL point. Hickman Creek sat far, far below us. There was a gully we might be able to rappel or scramble down, but we couldn't see how far it went. Even if we were able to get down, we'd have to cross the glacier's outflow, then climb up the other side and hope for the best. I didn't like the look of the gully, but knew that Mike and John would be the one's to make the decision. I just didn't have the experience to make the call. It didn't take long. They didn't like the look of some ice sitting over the top of the gully, and so we would camp here and consider out options.

I was still spooked at the crevasse thing and my ribs hurt whenever I tried to laugh it off, but helped get the tent up and gear stored. The sound of a low flying jumbo jet began to ring in my ears. Looking around, for there were no planes in the sky, I began to worry. The noise increased, then cracked, and a bus-sized block of ice broke off the side of the mountain and careened down the gully we had been contemplating just 30 minutes before. The sound echoed for several minutes.

Over dinner we plotted possible alternate routes to get to our food and to Hickman. All were on the dicey side and required rappelling down things that we could not easily get back up. In short, they were committing: If we went, we had to go through, because we could not go back. We had to know about the food on the other side. Out came the satellite phone. John dialed, looked quizzical, then hung up and tried again. And again. Each time, he got some sort of emergency recording, instructing us to call the service provider or the police. We tried one number, and then another, and then another. None got through. Thirty tense minutes passed and I began contemplating a way out. We had, stretching it, two and a half days of food and fuel to get us back to Arctic, which was the nearest extraction point. If we couldn't raise Doug, it meant that we would have to sprint, as best we could, from Arctic out to a highway. This would involve a lot of bushwhacking and very, very dubious river fords. Even then, we would have to either swim across a lake, or hope that someone on a boat would spot us. Although the distance wasn't great, the terrain was difficult enough that speed was impossible and even getting through a little unlikely. Moreover, thrashing through the brush in prime grizzly country was not exactly a swift idea. From Arctic to the highway was, I thought, about a week's worth of hard work. A week with almost no food. We would survive, hopefully, but it would not be pleasant, and it would leave scars. I began to darken.

"Uh, hello Doug," I heard John say. Apparently, one had to dial 001 before the number, rather than just 1. Relieved, I untensed for a moment, knowing we wouldn't have try to walk out. I couldn't track the conversation, but when John hung up I was all ears. As things turned out, Doug had not been able to get the food drop down: The snowfield on the other side was bare ice, and heavily crevassed. The food buckets would have exploded on impact or rolled into a crevasse. There was no decision now. Retrace our steps quickly, before out food ran out, and then get picked up at Arctic. I thought about the warmth and certainty of the Appalachian Trail, about the comforts of having a path to walk that one knew would go through. About not having to worry about crevasses or minor starvation or satellite phones. About a place where one did not have to fight against nature to survive. I went to sleep unafraid for the first time in several days.

A storm raged all night with very high winds and rain, and occasionally something harder. The buffeting of the tent woke me up occasionally, but mostly I slept soundly and deeply, and awoke feeling refreshed for the start of our retreat. In an effort to conserve food and fuel, we each ate one packet of oatmeal, dry. I barely noticed the 100 or so calories it provided. The skies were dark and ominous, but the wind had died and the rain had ceased. The dark skies meant we wouldn't roast on the snow fields, but neither was it terribly pretty. We retraced our steps, hustling past the seracs, on something like a forced march. We'd stop every thirty minutes to get bearings on the GPS, but mostly we just hustled. We dropped down the snow slope to our camp from two nights before, and continued to run the rocky moraine until it ran into the glacier, forcing us onto the ice.

Visibility dropped to a few meters, although occasionally the wind would shift and give us a minor glance at our future. Mike would take a bearing on the GPS, and we'd go in a straight line for a while. Run crevasse, take a new bearing, and go forth again. Technology, in such a setting, is a good thing for the unskilled (like us). Pushing forward, we ran smack into a large, rocky island complete with a running water supply and some minor wind protection. Good enough for now. The low temperatures and damp air forced all my clothes onto my body, and still I was cold. A large pot of Extra Hot and Sour soup helped to warm me up enough to look over the maps with Mike and John. Not wanted to go down the way that we came up, we started looking for an alternate route back, mostly to avoid the heavily crevassed glacier we had to come up initially from the Snout of Mess camp. Mike has the mapskill so necessary for this thing, and almost instantly had a good looking route in mind. The only trick involved a 1000 meter descent on steep rock.

We had been frugal with our food today, but were still short on everything but dinners, of which we had enough. The one packet of oatmeal, dry, had been followedby a power bar and a handful of yoghurt covered raisins. Maybe 400 calories before dinner. Fuel was holding. In a good world, we'll make Arctic Lake in two full days and be picked up the next morning. Of course, the weather could close in, like today, and we could sit at Arctic for a week. I actually didn't dread this very much and felt surprisingly serene. Despite the cold, and the taunts from Mike and John at the peculiar smell of my feet, I was able to sleep and sleep well. Something about having a picture of the future was helping my mindset immensely.

The foul weather had broken and we had pleasant skies and nice sun to lounge in over breakfast. The rock island was so pleasant, in fact, that despite our dwindling food we laid about in the sun for quite some time before setting out down the icefield once again.

Unfortunately, the clear weather meant that the sun had an unimpeded path to all the white stuff around us and the icefield became something like an oven as the morning rolled into the afternoon. We climbed up onto a snow field, roped up as always, and traversed toward a prominent peak in the distance.

High on the plateau-like snowfield, the walking was easy and the clear skies, though hot, gave us unobstructed views of the land around us. It didn't feel like we were retreating after a failure. Rather, it was fun. I was a little worried about the descent down the rocky cliffs that we were approaching, but this was minor and the enjoyment of being in such a splendid place was overwhelming.

Near the large peak we encountered a massive bergschrund which might have proved interesting had we been keen on climbing up the peak. None of us were in the mood, however, and we simply skirted around it after taking note of its freakish nature.

By three in the afternoon we had reached end of the snow and the start of the rock. Staring down into the Mess drainage, we could almost see the Snout of Mess camp that we had set last week. On the other side we could spot the Arctic plateau, along with Illini peak, which sits above Arctic Lake. It looked much more impressive from here than from the lake. The only hitch was getting down, which didn't look too bad, and getting up the other side through the green hell. That looked as awful as I remembered it.

The descent was steep, and somewhat loose, but John and Mike had no problems with it. I moved slower, significantly slower, but safely and comfortably. Midway down the descent we encountered a large flowered filled meadow, whose scent I had been picking up ever since we left the snow. After a few days surrounded by rock, snow, and ice, the greenscape and powerful floral smell were almost overwhelming.

I plopped down next to John in a large patch of lupine and luxuriated in the surroundings. None of us wanted to leave such an Eden and we indulged ourselves by sitting in the flowers for an hour before our food situation demanded that we move on a bit further.

The rest of the descent to the Snout of Mess was steeper than before and my legs began to fail me. John and Mike continued at goatspeed, leaving me far behind on the rock. I could see them look back occasionally to see where I was, but eventually they rounded the base of the glacier and I was alone in the land. Quads burning, I couldn't see how the others could move so quickly down the rock. Skill is required in going down, and I did not have it. I could power up slopes easily enough, but power meant nothing where quick feet were required.

I finally reached level ground and wandered along the side of the glacier to where we had camped before, whipped. John and Mike were gathering wood for a fire, but all I could do was sit and rest. Gathering strength after 30 minutes of idle activity, I helped get the tent up, fetched water, and started cooking our multicourse meal. We had, more or less, two full dinners left and, with luck, this was all we would need. It would take us a day to get to Arctic from here, and hopefully Doug would be able to get us the following morning. Extra Hot and Sour Soup, home made and home dried Bengali red lentils and rice, and evening tea accompanied the raging fire than John set. We even felt good enough to stay up until the sun went down and the world was somewhat dark. Midnight is a long time to stay up to see the sun set.

Despite our food issues, none of us wanted to leave camp in the morning. Facing us was a long day of bushwhacking back up to the Arctic plateau. Coming down had been one of the least pleasant experiences of my life, and I could only hope that we would find a better route up, or at least that some how gravity would be my friend today, instead of my enemy. It wasn't until 11 that we finally had the tent down and were moving toward Mess Creek. The Universe smiled on us and a nice game trail led all the way to the creek without having to do much bushwhacking. The water was higher than before, but still didn't present much of a challenge, now that our packs were mostly devoid of food and so quite a bit lighter than when we had crossed in the opposite direction.

The ascent up through Green Hell was, surprisingly enough, much easier than the descent, although still not a walk on the Appalachian Trail. Where I had struggled on the way down with my lack of skill, Mike struggled on the way up with a lack of power. Where I powered up, Mike had used skill and knowledge to descend. It was a trade off, I knew, but I still wished I had more skill. Nearing the top, tired and sweaty, the grade steepened to about sixty degrees and I found myself at the base of a meter tall root bundle, surrounded by trees. Their resistance kept pushing me off and I struggled for several minutes trying to get up and over. I finally took out my ice axe and swung into the ground above the roots, using it to pull myself up. Another 10 minutes and I flopped over on clear ground at the top, barely able to speak to the rarely smiling John. Another 10 minutes passed and I was still tired, but now Mike had arrived, which gave me someone other than myself to poke fun at. But, we were now up on known, easy land. The Arctic Plateau felt like home, and I welcomed the lupines that spread out over the mist covered land.

After resting for nearly an hour, we shouldered our packs again and rumbled off. Despite the occasional sprinkling of rain, my spirits were higher than they had been on the entire trip. The mist would roll in and out, gracing the land with an eerie quality that felt very much right. The flowers and the mountains and the gentle terrain were welcoming and the walking was easy. No ice, no snow, no crevasses, no bushwhacking. Just rumbling.

John detoured over to burn up crates of core samples left behind by miners (they are supposed to dispose of them), but mostly we cruised along, happy to be on the plateau and trying not to think about the possibility of extended bad weather: Sitting beside the shores of Arctic Lake with no food (it freezes and holds no fish) for several days wouldn't be pleasant. Everyone was happy. I made a funny joke about Mike during a rest break, which became magnified by our mood to a side splitter.

Illini Peak came into view as we moved north along the plateau, casting its spell upon us. Arctic Lake sat at its base, and that was the end of our trip. The mist cleared and the sun came out, as if someone was telling us that things had worked out for the best, that we had come the right direction. Cresting a hillock, we looked down upon Arctic Lake, our home for some uncertain length of time. Mike and I set up the tent while John roamed about picking up bits of wooden junk left over from miners for a final fire by the shore of the lake. We were able to raise Doug on the satellite phone and he agreed to come and get us the next morning if the weather would allow it. As the northern day began to fade into the pale dark of dusk, we sat around our fire eating dinner and talking about everything except the trip. This was appropriate, for at Arctic, we were at home. We might be miles from the nearest human, but this was comfortable, and comfortable places feel like home.

We awoke to a glorious morning and fed on the last of our provisions, knowing that Doug would have no problem reaching us. After getting most of my stuff packed, I lounged in the sun for a while until I heard the faint drone of a plane. Scrambling, we got the tent down and packed just as Doug splashed gently down on to the surface of the lake and taxied up to our shoreside camp.

We took a few final pictures before lifting off. Doug took us on an aerial tour of the Spectrum Range and alot of the ground that we had traversed the previous summer. It was a beautiful sight and we even spotted a variety of wild life on peaks and on the plateaus. I didn't know when I would be returning to the area, but I suspected that this would be my last time for several years. Mike and John were committed to the North. To going North. I needed, wanted, something else. They would return summer after summer to explore the area, to go where no human had gone before. My path lay elsewhere.