August 7, 2010

The rain has not been kind to Ladakh. This desert land is suffering under repeated cloud bursts. In Leh, the only city that seems to count, several hundred are dead and nearly a thousand are missing, presumably dead as well. The rains that had hit Brian and I during our trek and on yesterday's zero in Padum apparently pounded the regions further to the north and west even harder. The lack of city planning and the nature of construction in the area exacerbated the loose, weak land and entire neighborhoods in Leh had vanished under a flow of mud and rock. I found out all of this yesterday at the one bar in town, a grim affair in which I was actually unsure whether or not I should have brought along a symbolic eye patch and started by drawing a nice and stabbing it into the table for all to see. A rough place. But it had a certain charm there and I watched the satellite feed with the other locals while drinking my two beers. The footage was devastating. I hoped that Ish and his brothers and the family at the Old Ladakh had been spared. This was all yesterday. And this morning, after a fourth, and final, meal at the Lhasa Restaurant, Brian and I hopped in a Tata for a lift as far as the driver could get us. Pigmo, hopefully. Our Indian friends made it into town yesterday, though as the all the roads in the area are closed to due to the landslides, they will be here for a while longer.

The ride was definitely worth it, as the massive valley was barren and, to be blunt, rather dull. The driver powered us along, stopping only to nearly beat a four year old who throw a rock at his ride. I think the boy would have gotten a thrashing if Brian and I were not looking on. The Zanskar river was well up and, though it had come close, the road was not washed out. But at Pigmo the bridge over it was completely swamped, with nearly 300 meters of coursing water to cross just to get to the bridge, and then another similar distance on the other side. Given the speed and the consequences of a slip, we opted to return to an earlier bridge at Zangla, which we were able to cross easily and start the second half of our traverse back toward the Indus.

We hiked across the barren flats on our own. I watched the wind whip the clouds about and wondered if we would see more rain or what the conditions of the river crossings might be like ahead. We had a long way to go and, if they conditions along the trek were remotely like what we had seen so far, we would have a very wet and wild time of it. The town of Pishu was our destination, which we reached an hour after leaving the Tata. A parachute tent was on the far side of town, set on the side of a large open area perfect for camping. The usual 100 Rs fee took care of our lodging for the night.

The town of Pishu seemed prosperous. Many animals were been watched over by a few local women, mostly old, and young children, along with several very lazy dogs who seemed to like the dung piles that had been collected for later use as fuel.

After some tea in the tent, Brian and I set up our tents and lounged about as triumphant Germans and French arrived, behind their guides, having completed, more or less, their trek. All that was left for them was to make it to Padum, though they had some notion about walking all the way there. Two Danes, some of the only independent trekkers we had met, came over and chatted with us about what we'd be seeing over the course of the next week or so. It was with some pleasure that we talked with them, as independent types were few and far between in Ladakh, or at least they were out on trek, and independent types usually make for fun conversations. The weather was holding, for now, and I hoped for dry conditions. Not just for myself, but for the people of the region, many of whom were losing their lives under the onslaught. It was a black time for them.

A storm battered our open and exposed, and beautiful, camp overnight, buffeting the tent with high winds and pounding the already saturated land with yet more rain. Somewhere someone probably lost their life in another slide. People are dying and I'm hiking. The morning broke cold and clear, with only a few remnant clouds left over from the storm. Today we would follow the river valley for a while before climbing up and over our first pass, which would bring us into the mountains and out of the relatively flat table land by the river. That is, we would after I fixed the stove once more. My hands were becoming permanently scented with the stink of kerosene.

As usual, we were the only ones moving at 6 am, but we would surely run into more groups coming out of the mountains today. Other than our Indian friends, we had not met anyone hiking back toward Leh, which confirmed my overall opinion of Leh as uninhabitable. The trail took us along the river before ascending steeply to a plateau affording excellent views of the river valley both up and down stream. And the dug out road bed on the other side, littered with bits of heavy machinery, on the other side of the river. The Danes had mentioned a powerful stream crossing near the town of Pigmo and we were anxious to get to it early in the day before glacier melt made it unfordable.

Despite the development officer's statements, it seemed that everything that was done around the valley, and especially in the mountains, was the result of the effort of the inhabitants of the villagers and surrounding inhabitants. This meant that anything beyond a small scale was difficult or impossible to pull off. Hence the lack of dams for flood control or irrigation (with Sara being the one example), and the precarious state of bridges. Bridges are hard to build if they are more than a few feet across, and the task is made especially difficult in a place like Ladakh or Zanskar that lacks things we take for granted, like trees. The bridge over the Pigmo creek was gone and the water had clearly been a lot higher in recent history. A little stub of a stone stairway was all that was left. Adults and large animals could get across, but the old and the young would have difficulty. We had some problems getting across, but made it without being swept away and flung down into the main current. I had a sore leg from a boulder that had been rolled down by the fierce current and hit me hard enough to leave a slight ding on my calf.

We hiked up and into Pigmo and found the one tea tent closed,

though in a few minutes of standing and looking like idiots we had a

crowd of local kids and young women staring at us. As in a dozen.

They almost seemed surprised to see us, and were even more surprised

when we kept hiking instead of waiting for someone to come and open

the tent for us. We walked to the edge of town and then took a late

morning rest in the shade of a rock wall. It was another two hours to

the town of Hanumil, passed

in a boring, but pleasant, manner, with a few diversions from the

river to higher plateaus to avoid washed out trail. The town itself

seemed to consist of one large house which also served as a

guesthouse, along with several large campsites and shacks for selling

tea and meals to passing trekkers. It was a pleasant spot. We decided

to take a room as it was 250 Rs for the two of us, or 200 Rs for the

both of us to camp.

After dropping our gear, we wandered over to the main camping

area, where the owner of the guesthouse also maintained a small cook

shack. Two other similar establishments were nearby. The issue of the

afternoon was how to proceed down the valley. The trail was washed

out by the river and there was a 30 feet section of serious climbing,

or a long, long detour up and over a minor pass. A fall would result

in being dunked in the river with a full pack and with the river

swollen by the rains, it would probably be fatal. In the below photo,

the trail runs along the base of the vertical banding. The pass is in

the upper left, but not on the skyline. We watched groups coming into

Hanumil make the long trek up and over the pass and down to us. But

that was a problem for tomorrow.

It was pitch black when I fired up the stove outside the guesthouse. But it was quite light before I finally was drinking my morning tea. Another session of cleaning and tweaking and begging the stove to work resulted in a later than expected morning departure from the guesthouse. It had not rained over night, but it was overcast and cool in the morning, which I was happy about. We were going to head over our first passes today. We were going back to the mountains. The climb up and around the washed out trail was steep and sweat inducing, even with the cold air. It was loose, slippery, and unpleasant, though straighforward. It was only 30 minutes to the top, but a hidden gully and a tortured set of water courses turned what should have been a 10 minute walk along the water into a 90 minute sweat fest.

The road snaked along the other side of the canyon wall. We

slowly gained elevation and legged out another hour of effort. Our

food supplies were just not that good, I thought. We had had some

difficulty finding trekking food in Padum, though we had cobbled

together what we thought was sufficient. But it was clearly not, as

my body began to tired quickly and I soon found myself forcing my

feet to carry my body forward. The grade steepened into a gully and I

thought I had reached the top of the Parfi La, only to find that I

was only on top of a plateau, with another 750 feet to go before

reaching the top. My altimeter, which had been reading correctly,

told me that I was on the top of the pass, yet it was still well

above me. So much for the easy pass described in our guidebook. More

sweat and effort got me to the top thirty minutes after Brian got

there. A large Euro party was on top getting ready to descend.

I was too tired to do much other than sit down and look at the

work that was going to have to be done in the last part of the day.

The trail plunged down to a river and then went right back up the

other side, with the trail being clearly visible in the below photo,

especially at the top of the green strip. I was tired from the

effort, but there was more to it. In addition to the altitude, which

I should have been adjusted to fully, I felt a complete lack of

energy. I ate a little food out of my bag, hoping that it might bring

me enough energy to finish off the cheese. Unsalted, unroasted

cashews and yak cheese. Hard to fuel on that.

The descent from the pass was very steep and I reached the

bottom feeling even weaker than when I had topped out on the Parfi

La. A swinging bridge brought us to the other side of the river and

the start of the long grind up hill. The climb was worse than

expected, with heat and swarms of gnats to accompany me on my way up

the dusty, rocky trail. Worse, the grade got steeper as it went up,

compounding the general misery. Awful. One of the worse hikes of my

life. In an hour I had gained 1500 vertical feet and reached the top.

I sat in the dirt and felt sorry for myself. There were more gnats. I

rested for 10 minutes and then finished the hike to Snertse,

which was nothing more than a parachute tent in the middle of the

gorge leading up toward the rest of Zanskar. Brian was there, along

with many Euros and one of the Israeli's we had met in the Markha

Valley. Although Leh was jammed with Israeli's, we had seen only one

in Zanskar and only a handful in Leh. He, and the others, had a

handful of rather strange stories to tell.

The rains brought landslides to Leh and many people had died there. Foreigners were being asked to leave the region, and most of them had. The Israeli and the other Euros had been on trek when this happened, but that had gotten news via a satellite feed in a previous town. They had been held up for several days waiting for the water levels to lower so that they could ford a river. One of their guide's ponies slipped and fell and they had to help the guide drown the pony. It seemed like a rather brutal way to euthanize the animal. Very uncertain times ahead. Brian and shrugged out shoulders and tried to get some more calories. The other trekkers eventually left and we had the place to ourselves, with only the caretaker of the tent to spend time with. Although set in a spectacular location, Snertse suffered from the usual problems in Ladakh: Trash and shit. There was rather a lot of it. People have to crap somewhere, but the American custom of packing out or burning the toilet paper hasn't caught on with the Euros. Much of the trash is left by the ponymen, but the Euros, too, are guilty of leaving behind bits of plastic, bottles, and cans. I sewed my hat back together and thought about Shauna instead of getting too worked up about it. I miss her much.

It was perfectly clear out at 4:30 when I stuck my head out of the tent to look at the stars and start the stove, which fortunately cooperated and provided hot water for tea without the usual 45 minute repair session. We were moving up the gorge by just after 6. The steep grade lasted an hour, gaining 1400 rocky feet, some times clammering over boulders and ascending remnant snow fingers over the river.

The grade eased off and we enjoyed fun and easy walking

through the gorge, with only minimal water left over from the winter

snows. The path gained elevation very slowly and it was tempting to

linger and explore the many side canyons that branched off from the

main one. The gorge opened, providing more expansive views of the

surrounding mountains, especially as we broke through the 16000 foot

mark on our way to the pass. The last bit wheezed me a tad and I was

happy to take a well deserved break on top of the pass at just a bit

after 10 am.

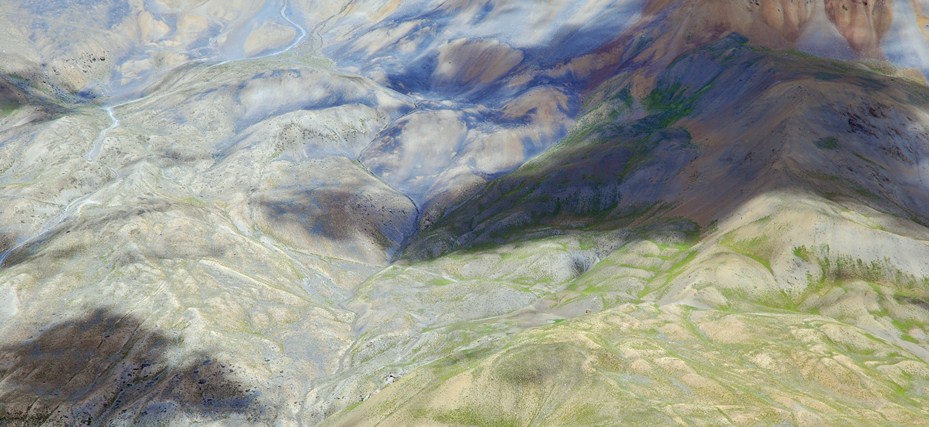

To call the view off the other side stunning would be

imbecilic. Moronic. And insulting to the land. It was one of the most

impressive, most tortuous, landscapes that I had seen, combining the

freakishness of the Grand Canyon with the power of the Rockies and

the colors of Abbey Country. Wave after wave of mountainous ridges

and spines, spires and buttresses, spilled over scene with glaciers

and ice fields dotting the higher regions, with every shade of green

and yellow scattered through the valleys below.

In the, seemingly, near distance was the town of Lingshed, and it actually looked like a real town instead of a glorified campsite for whitey. Green, irrigated fields sat below multi-hued, sculpted mountains. Three rivers ran down from above, cutting the town into thirds, with a large monastery on the far side forming our nominal goal for the day. Looked like we'll be there in an hour, after an easy and pleasant stroll. Both Brian and I are experienced enough to know that this usually means a long, long hike, but we could dream nonetheless,

We sat on the sunny pass, quite alone, and rested in the glory

of the land around us. Tourist-trekkers were becoming a scarce

commodity, a sign that the landslides forced another burden upon the

people of Ladakh and Zanskar and Himachal Pradesh. With the lost of

hard tourist dollars, the remainder of the year would be hard for

many people and families. Ish and his family would be suffering in

Leh, but in a couple of months would head to Goa and sell to the

Euros there. But what about a family that relied on the strength of

their ponies to earn enough during the summer to help get them

through the frigid winter? The slides would claim more victims over

time.

The descent was the typical Indian suckiness. Very steep, very dusty, and rather rubble strewn. We plunged 2400 feet in 50 minutes and reached a parachute tent at stream where, to our shock and amazement, a solo trekker sat resting, heading opposite us. An Irishman, he had stories to tell about the slides, stories that were later confirmed by the satellite feed (solar powered, of course) that was the caretaker's only companion.

The latest estimate was 150+ dead in Leh and 800 more missing,

which means dead but without a corpse being located as of yet.

Trekkers were apparently being airlifted by Indian military

helicopters out of Skiu and the Markha Valley. All roads (if you can

even call them roads) in the region were still cut, which was

complicating the relief effort. Only the airport in Leh was open,

with the rest of the aid workers doing their business via helicopter,

if they were working outside of Leh.

The Irishman was more exotic than anything we had yet seen in

Ladakh or Zanskar: An independent trekker carrying his own gear.

Nearly everyone we had met had ponies and mules and people to set up

their tents and bring them tea and wipe their arses for them. Someone

to walk them down the trail and make sure that they didn't stray too

far from the standard route and reassure them that everything would

be ok. The rarity of the independent backpacker was on display every

time someone reacted in amazement that we were carrying our own

houses and kitchens. Irish was heading in the opposite direction,

which we were a bit sad about. Independence, oddly enough, seems to

breed community, whereas tour groups seem to breed isolation. That

is, at least, in relation to the other people one meets.

We chatted for a while a watched the news over tea and noodles before starting the long and sweaty trek into Lingshed. Rather than being a nice, direct route down from the pass, the trail had to cross a sequence of ravines and gullies, following a tortuous path toward the town. Along the route we passed a work party from Lingshed that was repairing the local bridge which had been washed away in the rains. The work party was eating some sort of ceremonial meal of lentils and rice and insisted through hand gestures that we scramble around on rocks after fording the river that they bridging. I wasn't quite sure of why, but their desire for us not to walk through the patch of ground where they were eating was obvious and we had no interest in upset them. We crested one last rise and finally reached the final descent down to Lingshed.

Lingshed was a large and prosperous village with a prominent

monastery marking the center of the settlement and green, irrigated

fields ringing the perimeter of the town. We stopped at the monastery

to inquire about camping or a room, but the old monk we found could

only show us a dark, dank, windowless cell, which didn't seem like

the nicest of places to sleep. He pointed us to a campground a few

hundred yards away and we settled in to a patch of dust for the

night. Views were not lacking.

Brian and I downed a pot of tea and were surprised by the attention given to us by the trekking party that was also encamped here. A French couple (as in two) was accompanied by four support staff and what looked like six horses. They had been sitting in Lingshed for, apparently, three days trying to decide what to do. Like us, they were heading toward Lamayuru and had had a difficult time getting through some of the rivers we had crossed recently. Many ponymen had been returning from the Lamayuru direction with tales of impassible rivers and washed out trails. But rather than simply going ahead and seeing if things were really as bad as reports made them out to be, they instead were stuck in indecision. The guide had never made the trek (so, what use was he?) and wanted to return to Padum, that being the safer choice. The couple asked us for advice, which was simple to give: Go ahead and check out things on your own. Carrying your own stuff if needed and be done with it. If things get too hard, turn around. But the couple, like most other Euros we had met, had no experience in the backcountry and were completely unprepared, either physically or mentally or materially, to do so. They pondered and went in search of a phone to try to call someone for advice. They were still looking in the village by the time we had finished dinner and gotten into our tents for the night. Even if the route ahead was impassible for horses, it could most likely be pushed through oan foot. Even if it wasn't there were at least two other ways through to a main village along a road. Something would go through. We just had to find it. To find it, we actually had to do something.

The French were up and about, and waffling again. They were moving

forward. They were going back. They were going to stay. We packed up

and spent an hour drinking a pot of milk tea. Lingshed was a

beautiful place that would have made for a great base to explore the

area from. But we were moving on, with a few more passes to go before

we reached Lamayuru.

We started out later than usual due to our excessive tea consumption (a second pot went down easily) and a desire to see what the French would do. In the end they decided to return from where they had come from and hope that the roads there would be repaired and open in time to catch their flight home. The guide was happy. We marched up the hill and in to the sun, picking up a local woman along the way. She was heading for a village that we would be passing close to. Goats and sheep were our other companions. The little buggers were being driven forward by two shepherds and seemed quite content to walk with us to the next pass.

We ascended to the pass, really a low notch between two

low ridges, and rested on top. The views were as always. It wasn't

that I was bored with Zanskar or Ladakh. It was just that I was

pretty sure what we'd find down the trail. The magic of trekking was

dulled by the sameness of things. There were no trees and only a few

bushes more than knee high. We were going to descend steeply to a

river, drink some tea, and then ascend steeply to another desert

pass.

And this was what happened. We did see one Euro couple hiking

away from their handlers, but other wise the routine was the same. We

reached a place marked on our maps as Shingo La basecamp,

but was really just an area of flat-ish ground with a creek and a

parachute tent. Three ponymen were inside. They had come from

Lamayuru, which was apparently passable, if difficult. The French

would have liked to have known that. And they would have if they had

just walked forward for a little while. But they never gave

themselves that chance and instead allowed their fear of the unknown

to force a decision on them that rational arguments could not defeat.

That is the nature of fear, I suppose.

Our last big pass was not far off from our cold, dusty campsite. It was hard to get moving, which was not a good sign for the day, or for the rest of the trip. I was tiring. I was tired of battling the stove every morning and then again in the evening. I was tired of the stink of kerosene on my hands, shirts, sleeping bag. Everywhere. We set off for the pass, with Brian quickly moving in front and gaining ground on the pass at a much higher rate than I could muster. I plodded.

The trail gained ground steeply, then backed off and let along

in a mellow sort of way, meandering around below the pass on a sort

of plateau, as if unsure of itself. I took a rest on a boulder in the

sun and ate some yak cheese. It was the best food I had in my pack.

The views were stunning and it was quiet and still, with a pleasantly

icy breeze. But I was tired, and the pass was still above me.

From the plateau it was only another thirty minutes or so to the top of the pass, where I found Brian shivering in the wind and the cold of the pass. He had been there for forty minutes and had to get moving again. We agreed to meet at a parachute tent that we could see in the distance and set out. I sat down for a rest of sorts, alone on the pass with just the blowing prayer flags for company. Tired. Tired of not being able to breath completely. Or eat a raw vegetable. Tired of the color brown.

The view from the pass was stunning, with the colors of the

desert and the mountains well mingled and mixed into a spectrum of

tints and hues and shades that made one think of the paucity of

imagination shown by Crayola.

I had experienced this sort of thing before, and I hated when it happened, for I was the sole cause of it and knew, rationally, that I would regret things later. I was in stunning, powerful place. And I could have cared less. The stripes and striations and waves and folds and spikes of the land combined with the colors and textures from the sun and the clouds and the minerals and rocks. It was beauty.

But there was little connection. I could see, but I could not appreciate. I took photos knowing that they would not help in the future, but that they would remind me that I was there, in that place, at some point in my life. I took a picture of myself. It was what I had to do.

I set off down the path from the pass after 10 minutes, meeting a sixty horse train coming from the opposite direction, completely unloaded and empty. No tourists. All gone. People would not have a happy winter, but at least there would be less trash blowing around. The tourists had all gone home. Been sent home.

I linked up with Brian at the parachute tent and quickly tucked into a bowl of instant noodles and two fried eggs while chatting with Brian and Sir Grumps a Lot, whom I haven't mentioned until now only because he said almost nothing during the four days that he had been following us, except to grunt. He grunted at me. Grunted at Brian. Grunted at the ponymen. After a rest, Brian and I set off together for the next village, which was several hours ahead and on the other side of a low, minor pass. As if to mirror my mood, rain clouds came in, dropping a soft, misty rain on us.

As I hiked along I thought of home and Shauna, which didn't

help my spirits much. The barren land, as striking and austerely

beautiful as it was, was brown and brown and seemed one dimensional

in comparison to the rainforests of my native Washington. Ladakh and

Zanskar were exotic and beautiful, but they were hard places to live.

It took a hard soul to love the land here. I could only appreciate

it. Maybe that was why Sir Grumps-a-lot was so moody. The harshness

of the land was exemplified in the mud and rock slides. We headed for

a low pass in the distance, with a village on the far side as a goal

for the day.

Looking back at the Sengi La from the ruins of a herders

shack, I continued in my melancholy sidle, appreciating what we had

done and where we had been, but not connecting with it on any sort of

an emotional level.

Nearing the pass, Brian headed one way and I detoured to a

different notch. Not for any good reason, but just to have some more

stillness before we descended to Photoksur and drew the attention

that we always did as independent trekkers.

The village sat well below us and was surrounded by irrigated

fields, fields watered by ditches dug into the hillsides, ditches dug

by the power of humans and animals. But the location of the village

was not what drew my attention the most. Nor, as it turned out, was

it what Brian focused on immediately. The road. The road had been

blasted up and over the 17,000+ Sir Sir La and was clearly visible

switchbacking down the slopes, like a smoothly carved scar. It was

hideous. It would bring commerce to the village. Maybe help people

get out of the mountains, at least when the road wasn't snowed in. A

good, 4 month road. But the presence of the road meant that the

village was no longer of any interest to trekkers, at least the sort

of trekkers that I liked to be around. Fat Euros might like it, I

suppose. And the locals, like the Navajos outside of the Grand

Canyon, can sell trinkets and their quaintness to people with more

money than sense.

We descended down a steep trail and made our way to a raging

river, where a work party was in place preparing the area for a new

bridge, the old one having been swept away by the floods. A rickety

looking bridge was in place for temporary transit. I crossed it with

some nervousness as I reflected on the fact that I outweighed the

typical villager by a solid 80 pounds.

We scrambled up the hillside and into the village, where we

were met only by the local kids, as the adults were down in the gorge

working on the bridge or in the fields. We milled about and talked to

a few of them in broken English and eventually were led by one of

them to a house where a woman took us in for the night as a homestay.

Her uncle was staying as well as his house had been buried by the

rock slides. The grandmother was there as well. And others. The

family had lost members and tears flowed quickly when the topic came

up. We could see the remains on the outskirts of the town. It wasn't

that some random people had died. Their people had died. The tragedy

was very, very real to them. Beyond the deaths was the loss of the

houses and fields, which would not be covered by insurance or bailed

out by the government. It was going to be a harsh winter in

Photoksur. It would be a harsh winter throughout Ladakh.

The mother and grandmother made us milk tea and chapatis with eggs for breakfast in the morning and we set out for the road with something approximating a full stomach, which was a rare occasion out here. The road had devastated the trail, with only bits and pieces still visible cutting between swithbacks on the road. No construction was taking place due the rains. The crews were elsewhere working on repairing the other roads in the region.

It took three and a half hours to reach the top of the Sir Sir La

and its stunning view. Brian had long since left the top for,

presumably, a parachute tent somewhere below the pass. I wasn't in a

good mood, despite the beauty. The road was what did it. The scraped,

graded earth was enough to destroy the place. There was no reason to

come here for trekking, though perhaps experienced guides could lead

one through the region without the road interfering. But this was

unlikely, at least for now.

It was the start of industrialized outdoor tourism; a cancer

that Ed Abbey wrote so forcefully about. The road was being built

with the best of intentions; there was no malice coming from the

people responsible for it. But it was misguided and a waste and would

destroy yet another place that nature had preserved so far from human

ruin. We have enough roads. People have evolved to survive in the

environment without trucking in Cokes and Maggi. But soon the road

would be bringing in tourists to gawk and spend hard currency.

Israeli's could ride motorcycles to the village and get high. The

French could be confused. And the Americans would have yet one more

place they were afraid to go to.

I felt like I was seeing the death of the place. It had

already died, but was just now getting around to breathing its last

breath. This place, with all of its beauty, was not going to be the

same any more. The road would continue through the valley until it

linked up with the road at Padum. It wouldn't stop now that it had

started. It never does. And you can get back to the original, no

matter how many signs and interpretive centers you erect.

I walked down the road and descended the pass for the ubiquitous

tea tent below, where I found Brian warming himself with a cup of

tea. I joined him and frumped a bit. My trip was over and I wanted to

go home, rather than continue adventuring and hoboing and

experiencing all the joys and thrills of travel in a foreign land. I

wanted to go home and have a been and start looking for a house with

Shauna. I wanted to be domestic.

We hiked cross country to save a bit of distance on the twisting road, dropping through a gorge and crossing a bridge that had been damaged by the floods. The road ran straight down the rest of the valley. I wanted a jeep to come by and sweep us away to somewhere else. Anywhere else. The beauty of the place could do nothing for me.

There was nothing else to do but walk down the road. Always

the road. Occasionally a bit of green by the riverside would herald a

small village. But it was otherwise empty and desolate, the road

workers having been called elsewhere to repair more important,

military roads.

We came upon a prosperous looking toward and quickly found a

few locals who volunteered to take us in. This was how it always

seemed to work: Locals would see us and jump at an opportunity for

some hard currency. We were led to a dank, smelly room with water

damage and a few blankets. As always happened, once we came in and

took our shoes off the rest of the family, and friends, and random

people, would come by to gawk at us. They all wanted to have a look

at the strange people who had come into town. It was something you

put up with rather than enjoyed. Once they had had their view and

left us in peace, we took a nap on the floor, at least we were until

an irate women came in and reclaimed the blankets. An argument

outside ensued and we pondered moving on for more comfortable

quarters, such as a clean patch of dirt down by the river.

I tried to make dinner, but the stove once again wouldn't

work. I through up my hands and decided to go hungry tonight, for the

only other option was to eat whatever the locals were eating and I

was tired of that, tired of having to smile and speak in broken

English. I would rather be hungry. I tossed the broken stove on the

ground and went down to the creek to scrub the kerosene off my hands.

The view from the water was immaculate, and I sat on a low stone wall

watching the sun dance on the desert mountains in the distance. I

felt better.

I spent twenty minutes on the wall and felt better. Felt more

calm. More tranquil. Ready to face the world again. I returned to the

room and wrote for a while as we waited for dinner to come, for I had

relented in my notion to go hungry. The husband and wife of the home

brought dinner us to up and watched us as we ate. Rice and greens,

with a fried egg. I ate a respectable amount and then pleaded

tiredness and proclaimed an early night to be what I wanted. I

stretched out on my back and looked at the shadows in the room move

across the willow roof, laced with cardboard. I could live here. I

could thrive here. But I was glad that I did not. I was glad that I

was going home soon.

Both of us slept surprisingly well in the smelly room and I felt much better than I had the night before. We didn't wait for breakfast, but rather packed up, paid, and were hiking down the road just past 6:30. From Hanupata the road descended into a tight gorge with beautiful multicolored walls. The road was literally blasted directly into the rock and couldn't be expected to last more than a season or two before a flood swept it away.

The gorge tightened yet more as we reached the confluence of

the Yapola and Shillakong. This was a place of supreme beauty and

serenity, with the muscularness of the rivers foiled nicely by the

delicate striations and colorations of the walls. Even for jaded

scenery snobs such as ourselves, we found the place to be stunning

and babbled at ourselves, searching for words to bring worth some

meaning to the other. The confluence of the rivers was a place of

beauty. And it was also a bus stop. That was spray painted on the

canyon wall, so we knew it to be true.

After the bus stop the road climbed out of the gorge, or

rather the gorge ended, and the track became paved. The walls went

away and the sun began to beat on us as we progressed toward the

Lamayuru-Leh road, which we realized that we might be able to make

today. We might be able to make Leh tonight. Not that Leh was a

desireable place to go, not by any stretch of the imagination.

As we progressed down the road we began to see more signs of civilization; more metal signs. A van passed us, heading up canyon. A few hikers with a large pony train in tow. We were getting closer. Perhaps the access road to the Lamayuru-Leh road might be open? Perhaps? We pushed on with the idea that today was the last day of the trek, and the last for me this summer.

We hiked into the town of Phanjila and took a seat at some

tables out front of a store, where a van was parked. I celebrated

with a Pepsi. We mingled at the table with some locals and managed to

find out that the road up ahead was cut, but that it was passable. We

could get a ride for five kilometers or so, and would then have to

hoof it to the road. Fine. I didn't care. It was hot outside It

turned out that the road was in somewhat worse conditions than the

locals knew or cared to communicate. We managed a lift to Wanla and

then set out with five locals for the main road. The access road had

been devastated by the floods and there were numerous washouts that

would take quite some time, and plenty of capital, to repair. The

drop offs required some effort to get down, and a few of the climbs

were technical in nature, not something appreciated by the locals we

were hiking with.

The hot sun beat down on us as we reached a paved road on which there was minor traffic. Along it we hiked, following the locals lead, but quickly outpacing them in the hot sun. This road was apparently built by the engineers who actually passed their classes, for there were culverts built and drainage improved. The asphalt was smooth and level and the road was sufficiently above the creek to preserve it from floods. We hiked down the road in boredom, with only an Indian boy laying in the road to provide us with a sense of strangeness. We thought he was dead when we reached him, but it turned out he was just listening to the ground. We passed by and he woofed at us, then scampered around and continued to listen to the ground.

A few miles down the road we reached the main track between Leh

and Lamayuru, at which a Punjabi dhaba was located. A few plastic

chairs outside of a grimy cafe manned by Sikhs was about all there

was, but this was our place to get back to Leh. A plate of beans and

curried vegetables with rice was the best thing I had had since

leaving Padum. There wasn't any traffic on the road, except for truck

and truck of a military convoy. This was going to take a while. We

waited and waited and waited. A few hours later the first passenger

vehicles showed up, but they were completely packed. We should have

just gone over the mountains and into Lamayuru. Should have, but did

not. We sat some more. Another hour passed. And another. A massive

Tata rolled up, hauling nothing of note, and an obese Brit rolled out

of the cab, clad in khaki shorts and a flowery shirt. Pink and

burned, he was having the time of his life. I chatted with him a bit

to get his story. Former hippie, had spent time here forty years ago.

Was back to relive his youth. He had friends with him this time and

the money to do it more comfortably, but was choosing to do it as he

had when he was broke and living on a thread. He was heading to

Lamayuru, and then eventually Padum. It would take him more time than

it took us to walk it, but I suspected he'd have a better time of it.

Attitude was king. I asked the driver if he would take us to Lamayuru

and off we went in the cab of his brother, who was caravaning with

him. It was in the opposite direction from Leh, but it couldn't be

any worse than Leh and was highly probably that it would be a good

bit nicer. After many hours of waiting it felt good to be moving

somewhere, anywhere, under the power of something other than my own

two legs. The road quickly climbed up and into the mountains along

unpaved, treacherous roads. I hardly noticed the multi-thousand foot

drop offs or the narrowness of the tracks. The chickens we were

riding with furnished entertainment enough.

We paid our ride a few hundred rupees and hopped out of the truck at the side road to Lamayuru, along with the fat, happy traveler and his friends. It was a pleasant site: Green and lush and definitely manageable on foot. Serene, almost. And it wasn't Leh. Barstow would have better than Leh. Anything would have been, even the Ninth Circle. Ok, maybe Leh isn't that bad. But I'd be quite happy sentencing Glen Beck to spend a lifetime there. Brian cut cross country while I strolled down the switchbacking road and we met up thirty minutes later at some under-construction homes to find a place to stay. As always, this wasn't hard. A friendly man who was the owner of the not-yet open guesthouse took us back to his posh family compound and put us up for the night, along with food and showers and soft beds. A big smile helped his cause. Mr. Gonboo was his name, and he had four daughters and was clearly a man of means in town.

After a nap it was time for dinner and yet more skiu, which was fun the first time, edible the second, and endured every time, every countless time, after that. Gonboo's daughter's version was better than most. He also broke out a plastic bottle of homemade spirits, called arak for us to try, though with Brian abstaining I had to do double duty. Gonboo was quickly even more happy and cheery. In the creaking home we settled in for the night and with the lights out I could think in peace for just a little while before slept grabbed me. I was enjoying the strange uncertainty of the way back to Leh almost more than I had been the trekking. It was odd, it seemed, to enjoy the unknown of the front country more than the world class sites of the backcountry. I was actually looking forward to tomorrow and what it might bring, which was something that I hadn't been able to say for a while. The sheer beauty of the land had been overshadowed by places and people far away. And now I was once again happy to be doing what I was doing, and being where I was. And that was a good thing, I thought, laying there in the dark on the straw stuffed mattress.

We had nothing planned today, and so we did nothing. Mr. Gonboo, the owner of the house where we were staying, took good care of us. Or, more accurately, he made sure his daughter's did: Nice chapatis and jam, along with rich milk tea and an omelet, were brought out for breakfast. We did need to find a way back to Leh. Neither of us wanted to get on to a public transport, which meant that we would have to throw money at the problem. After breakfast we headed up to the famous gompa, but found not much to look at. It seemed that in recent memory the monks had closed up most of the interesting areas of the gompa, leaving us with a small stone courtyard to look around in. It was made of stone. We wandered the hallways, but there even less of interest there. To say that the gompa was disappointing would be an understatement, especially as I had been focusing on the destination for several weeks now.

The reasons for the closing off of the monastery were unknown

to me, but I assumed that the monks got tired of gawkers and their

flashes. That is what happens in living places when they become

comparatively accessible by tourist masses. Most of Phuktal was

closed off as well, but that gompa was in such a stunning place that

it didn't matter at all.

Our trip was more or less over, except for time killing on my

part. Brian was going to stay for another two weeks to do some more

trekking and to summit Stok Kangri. I was tired of India in a way

that I hadn't expected, but probably should have. We milled about the

gompa and on the way out spotted a microvan with a taxi sign on it.

Eventually the driver came back to it and we started in on a

conversation that we had had, in a variety of forms, many times this

summer. “You want to go to Leh?” Yes,

we want to go to Leh. “You

want to go today?” Yes!

“Taxi can't go today. You

go tomorrow.” We

arranged to meet the driver in the morning and set a price of 3000

Rs, which ordinary would be a princely sum, but given the condition

of the road and the fact that we could get out easily to vomit, and

wouldn't be vomited upon, it seemed reasonable. Besides, this is why

I have a job.

I bought a bar of soap on the way back to Mr. Gonboo's, but

upon entering the shower (a room with a bucket of warm water), I

found that the soap didn't really do much for either smell or dirt or

grease. It just kind of foamed a lot, much like a brain dead rabid

dog might do. But I could at least claim to have showered.

I napped for a few hours and then ate a plate of white rice topped with a bit of eggplant. Following a debate with Brian about human nature and crises, I walked down to the main strip and joined a bunch of road workers at a collection of plastic tables for a bowl of Maggi and a tall bottle of Godfather. It wasn't even quaint. After an hour of watching the world go by I returned to Mr. Gonboo's to find a long line of road workers stretching for a block to his courtyard door. Somewhat puzzled, I went in to find Brian shelling peas with Gonboo's eldest daughter. It turned out that Gonboo was the local bootlegger, selling homemade beer (chang) and liquor (arak) to the road workers, most likely with the approval of the local authorities (so, a bribe). Very nice. We were staying with a bootlegger. At least it was a colorful way to end out trip.