Northern California: Seiad Valley to Ashland

July 19, 2003.

It simply should be possible, I thought on

top of the south Devil Peak, that there can be so much beauty in this

world. The land that I had walked through just shouldn't exist, according

to what you might here at home, in town. There are no wild places

left, people chant. The environment is being ruined by developers/the suburbs/

soccer moms/coal plants/big business/SUVs/loggers/enivronmentalist. Take

your pick, but everyone and everything will tell you that something bad is

going on in this land of ours and someone other than themselves is to blame.

I had walked for more more than 1700 miles, mostly through public lands,

though some on private holdings. I had seen the destruction of forests by

loggers and trash left by tree sitters. But, mostly, I had seen raw

beauty for so long that I no longer knew how I could live without it.

Here, on the south Devil peak (part of Three Devils Mountain), I could not

understand the negativity and pessimism of others. Just go for a damn walk,

I wanted to shout at them. Not only will you get a little exercise, but you

might understand how large this land is, how supportive it is, and how

important it is. Exposure to beauty was doing wonders for me and I wanted

others to get its benefit to. This land

does need to be protected, but that certainly doesn't

mean making it a park or a forest. Forests are designated to be logged,

parks have things like auto-touring loops and visitors centers and

RV parking lots. Just

hang a wilderness tag on it and forget it. Don't develop it, just let it be.

However...

The PCT could not have been built without help from the government. Nor

could it have been built without the help of private landowners. Nor

without the help of volunteers. A balance had to be struck. Let the

government protect the land and volunteers build the minimal amount of

structure necessary. If there were no volunteers, then let it stay wild and

let people roam about off trail. Keep a few rangers about to make sure that

people don't bring trucks and ATVs into sensitive areas. Maybe Abbey

was atleast partially right after all.

I had been out of camp early, although Will quickly passed me by. The

cool morning air felt so good that when I finally topped out on

South Devil Peak I wasn't neither tired nor sweating. The lofty, craggy

mountains and the perfect morning light combined with a soft, quiet wind to

give everything a feel of comfort and delight. I had to stop and do nothing

for a while, and so on the hard, craggy ground I sat, with the world at

my feet, with the promise of the blue land in front of me. Sharon came by,

smiling at the sight, although I hustled her on by telling her I was waiting

to go to the bathroom. I eventually scrambled a bit down the flank and

enjoyed a better bathroom than could be found in any millionaires mansion.

This place was just too good to be true. Millionaires, I thought, have it all

wrong. If I had a ton of cash, I'd leave it for when I was old and decrepit

and spend my days in a place like this, roaming and wandering in surroundings

more soulful than anything I could buy.

There is no getting around the season, and with the onset of the late morning,

the heat of the day returned, although the higher elevation helped mitigate

things to a certain extent. It was only in the low 90s as I rambled though

the country side, up and down passes, through meadows, and across the

occasional logging road. Cows were out here, their clanking bells and

stupid moos heard down in valleys, a reminder that I needed to start treating

my water again, at least until I cleared central Oregon. Oregon! Yes, today

I would make it to Oregon. Seventeen hundred miles across one state.

AT hikers are getting close to done after 1700 miles, having walked across

roughly 11 states. Although I spent lunch time with Will and Sharon at spring,

I spent almost the entire day by myself, lost in thought over California and

the best-ofs. The best town. The best breakfast/lunch/dinner. Which place

had the best dessert. What were the 5 best stretches of trail. Where was

the best hitch. The best water. The variations were endless. Of course,

I had a list of the best bathrooms, sunsets, sunrises, campsites, and

trees. The only thing absent was a worst-of category. There just wasn't

anything bad out here, as odd as it seems. I could never have imagined spending

more than two months without having anything to complain about, with having

everything work out well. It just didn't seem fair to other people that I

should get all this good fortune. Then again, perhaps one is at least

partially responsible for one's fortune.

I could feel the presence of others, as odd as that seemed. It wasn't a

broken twig or a stomped patch of grass or anything silly like that. Rather,

I could feel someone new out here. Perhaps it was a scent that I

could not smell. One's senses become extraordinarily acute when you spent

some time in the woods. I had long ago been able to smell freshly

laundered clothes for a mile before I found their wearers. Perhaps I

was smelling a new person. Even though I knew that there was someone

else out here, I was a little surprised when I began descending into a

grassy valley and saw a short, stocky figure ahead. Small pack, foam sleeping

pad on the outside, wearing running shoes. No doubt, it was a hiker. And

it could only be Rye Dog, the last of the front of the pack. Now, there

was a only a record setter in front. It took me more than 30 minutes of

hiking before I caught up with Rye Dog, and only did so because he stopped

where Sharon was looking for the trail. Tutu had described him well: Fuzzy

neck, but few chin whiskers or a mustache. Just like a blond, Amish

thruhiker.

Rye Dog, whose real name was Ryan, was something of a ski bum and great

fun to talk with. His register entries had consistently been of a wit that

I could really appreciate and that same wit came spewing forth at all

moments. A former amateur boxer and soon to be Bolivian organic farmer,

Rye Dog grew up in Rhode Island and lived frequently in Jackson, WY.

He was hoping that Beast and Tutu would catch up and was glad to hear

a report of a Tutu sighting. Rye and Sharon left me sitting next to a creeklet,

drinking water and taking one last break in California. I had only two miles to

go to the border, and I wanted the chance to be lazy for one last time in

the state. California had been good to me, and I once again went through

my various lists. If I ever became dictator, I was going to carve up

California to separate the good from the bad. The LA megaplex would extend

to San Diego and would be its own state. The Bay Area would get hacked

into its own governing body. The rest would remain California. The

California I had walked through was so much different than what people

usually thought of when Cali was mentioned. This land didn't deserve

Arnold and Grey, or the Lakers, or Silicone Valley. It was good, and

it was pure.

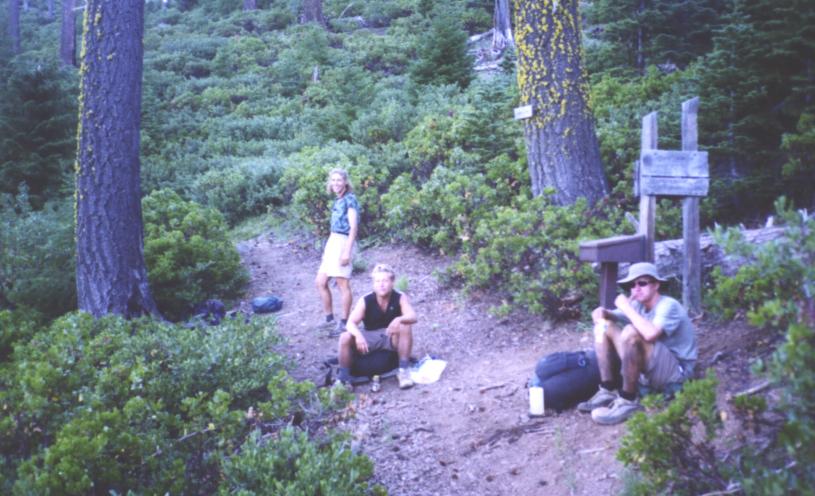

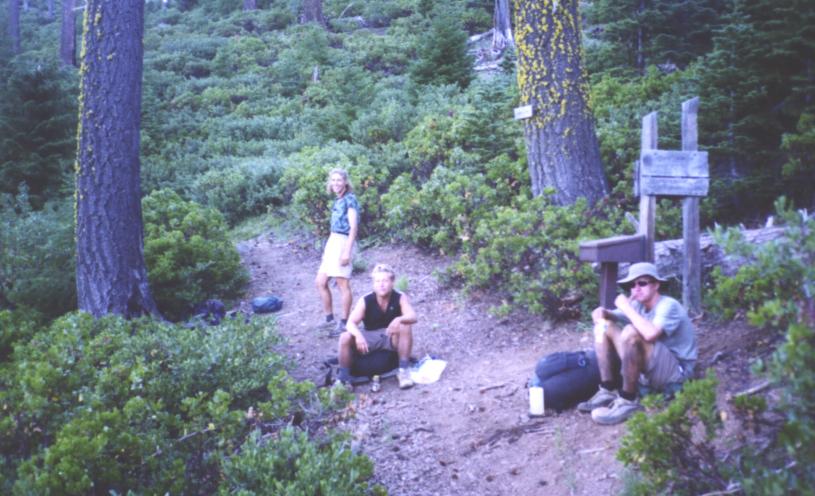

I found Will, Rye Dog, and Sharon lounging next to a tree, which could

only mean that they were at the border, and that meant California was

done. I stopped at a tree with a little wooden sign that told me

I was leaving one state and entering another. We all thought this

was pretty funny indeed. I don't think this humor would be appreciated

once I returned home, but it was comical now. Maybe it was just the

first-state-done exhilaration, but we were are giggly, like a classroom

full of 8th graders when the teacher brings in someone to talk about sex.

Food was eaten and pants dropped for a ceremonial mooning of

California (maybe it was just me with my pants down). Cali knew how

we felt about her, and this was all in good fun. Even though I had

long ago past the physical and temporal half-way points on the hike,

it was here that the spiritual halfway point was reached. I really

was now on my way to Canada, rather than simply hiking in California.

I hoped that Oregon would prove as good of a friend as California had,

and things looked promising when I found a nice, rocky knoll to

camp on. A knoll with a view was a bed for the night, and the others

seemed to agree. Nearly 35 miles today and I was still fresh. An

unobstructed view to the west helped, and as the sun sank below the mountains,

Oregon immediately felt like home. The same sun set here as it did just a

few miles to the south. Tomorrow afternoon I would reach Ashland, and

see the last of Will. He wasn't planning on going in, but was going to instead

eat at a restaurant on the I-5 exit where the trail came out of the woods

and then push on. He had enough food for another day or two and was

banking on resupplying at a resort in the woods just a little ways

north. He had five fewer days than I did to make it to Canada, and that

was important to him now that he was close. Glory was gone and soon so

would be Will. I must remember, I thought with heavy lids, to say good bye

in the morning, before he gets too far ahead. A last look at the

purple sky overhead comforted me some more. Not only was the sunset the

same, but the stars were just as perfect here as they were in a whole

different state.

Ashland was pulling me forth, calling to me. It would be the first actual

town of any size since South Lake Tahoe. It would be the first zero

day in a large town since, since when? Since Big Bear City, my first

zero day. The other days off had been in Agua Dulce, Tuolumne Meadows,

and Dunsmuir,

hardly metropolitan areas. Ashland had a reputation of being one of the

best towns on the trail, complete with brewpubs and summer long

Shakespeare festival. Twenty six miles separated me from the town.

Twenty six miles also separated me from the departure of Will. Unless

he got hurt, he was going to move at a pace that would not allow me to

see him again Twenty six little miles, after more than 1700.

Although the four of us had left at different times, with me in front as

usual, we were all together for a last time next to a dirt road with a

large, gushing spring. I looked about for the sheep that the spring

was named after, and finding no sign of animals, I drank freely from

the spring without treating the water, perhaps the last time I would be

able to do so for a while. Everyone was in good spirits, knowing what was

ahead. Rye Dog was going into town, but was not going to take a day off

tomorrow. Having him in front of us would be good: His register entries

were gems to be hoarded and anticipated, something I couldn't do if he

was behind me. Although we were altogether at the spring, an hour found

me all alone in the rear, with nothing but the waving grass that the

views down into the valleys around Ashland. Dry, parched valleys whose

heat I could feel, in my heart, up here. The heat that had been pummeling

me every afternoon since leaving Sierra City. I could see the

mountains in the distance and could only hope that the trail climbed

into them and away from the worst of the heat. The scar of the road

walk around the Klammath was still tender. In northern California I

had frequently thought of John C. Fremont and southern Oregon proved

to be no exception. Fremont was one of the country's most celebrated

explorers, though not in the same vein as people like Lewis and Clark,

Kit Carson, Jim Bridger, or John Colter. Fremont was a government

stooge (in some ways) and, apparently, something of a fool. He had

also made repeated trips through the Rockies and the Sierras and

even the Cascades at the head of one army expedition or another.

He traveled north from the central valley of California looking for

an easy route between the settlements of the valley (and so also

San Francisco) and the settlements in the Willamette Valley,

the terminus of the Oregon trail. Fremont had gone to the east of

the PCT, straight through the arid, though lower, lands that the

PCT was avoiding. His route never really gained much acceptance as

one for settlers or merchants and later one was found further to the

west, near the PCT in fact. Men like Colter and Bridger were capable

and gave me little inspiration that I could do this thing of mine.

Men like Fremont were halfwits and did give me inspiration.

The afternoon proved not to be terrible warm and I was able to gauge how close

I was getting to town by the increase in day hikers and runners. Since leaving

the Desolation Wilderness north of South Lake Tahoe I had seen almost no one

except for other thruhikers. Very few day hikers and no backpackers. Only in

towns or at road crossings would I meet others, and now that I was seeing

women running about in spandex and men in garish outfits on mountain bikes,

I knew that a town had to be close. I passed old couples with dogs and

young families without them. The dirt roads had cars parked along side the

edges and there were more trail markers. Clearing out of a thick wood, I

came upon a paved road and on the other side found Rye Dog and

Sharon sitting in the shade chatting away. Rye Dog was going to get a lift

into Ashland from one of the dog-following couples that I had passed a

ways back. In his words, the PCT "owed him some miles." I thought this

rather a good idea and tried to calculate if the PCT owed me something

as well. Unfortunately, the balance was not in my favor, down the trail

I would have to go to I-5. Besides, I wanted to say goodbye to Will,

something I had not done this morning, and I figured he could be found

eating at the restaurant not far from the trail.

Sharon and I had made plans to meet near I-5 to see Will off and then to

hitch in together. Hitching with a woman was much easier for

me than hitching by myself or with another male: The woman's

presence softened my bearded face and ratty appearance. On Sharon's

side, she would get a little extra confidence that nothing bad would

happen as I would be around. Of course, Sharon was an experienced hitcher

and didn't seem to have any fear of the process. The trail from the road to

I-5 was completely down hill on a dusty path, paralleling the road that

Rye Dog had flew down. As I dropped into the valley holding Ashland,

the temperature began to climb and I began to tire. With the tiring,

I became not disoriented, but rather distracted and missed a turn of the

trail. I was close to I-5 and could hear the roar of tires along the

pavement and so was not really lost. I had to walk through a bit of

private property before the interstate came into view, and then down a

road to get back to where Sharon was to meet me. I came upon her in the

shade and she expressed no surprise that I had gotten lost. Perhaps it

was because there was no notion of "lost" now. As long as I was generally

headed to Canada, I wasn't lost. I could only get lost if I got on a

bus and went home. Sharon and I started walking back down the road I had just

come up, heading

to Callahan's Restaurant, when we spied Will's lanky figure in the distance.

The timing was perfect, as he had just spent an hour and $20 at

Callahan's having a marvelous lunch and was getting ready to start back on

the trail.

None of us wanted to say the words, to admit that Will was really leaving,

and so we talked of everything else. Sharon and I gave Will our excess

food to help him on his way. He had been able to buy a few things in

Callahan's and had a very dubious resupply plan to get to Crater Lake.

Still, the three of us knew by now that things would work out in the

end, regardless of how much food he left here with. And so we

talked and talked, and an hour passed. By this time we left sitting by the

side of the road in the shade, doing nothing at all. I occasionally

scratched the poison oak infection that had begun to grow on my knee,

but did little else. An SUV drove by, then slowed rapidly just past us.

The reverse lights came on and the vehicle came back to us, the

drivers head out the window with an enormous grin on it. "Are you

thruhikers?" the man asked. We told him we were and he shut off the

engine and got out to investigate. We were, as it turned out, in the

presence of a legend.

The man had been part of the 1976 thruhiker crew, the first real

thruhikers of the PCT after Eric Ryback's initial hike a few years before.

The '76ers had been known for their massive packs and the struggles they

went through to get from Mexico to Canada. And here was one in the

flesh. Another hour passed in conversation, with the thruhiker

amazed at the size of our packs and how little they weighed. He

regaled us with stories, and we countered with our own, trying to

piece together what sections of trail were really different today.

Many were. The PCT's route had changed over the years, particularly

between the LA area and Tuolumne Meadows. The PCT had gotten easements

across various bits of private property and there was now good

tread in the Sierra. He offered to give us a lift into Ashland. He

was down here on business from Portland and had to go north anyways.

I looked at Will and saw the indecision. All it took from me was a,

"Hey, you could come in and see Terminator 3." and the four of us

were soon speeding down the interstate together.

The '76er dropped us off in front of the Ashland hostel and bid us

good luck for the rest of our walk before heading out of town. The

hostel was closed, but had a shady porch with chairs and a note

on the door welcoming us to the hostel's porch. As with many

hostel's, the guests had to be out during the day, although PCT

hikers were, I had been told, exempt from this rule. There just

wasn't anyone around to let us in. And so we dropped our packs

on the porch and set out to explore around town. Perhaps there might be

a cheap motel in the area. Besides, it was fun to walk around town

in the state we were in: Dirty, bearded, and obviously fresh off

doing something fun. In Ashland, and in other towns along the

PCT, this made us something akin to stars, and the further north

we went, the more solidified was, as Sharon and I came to refer to it,

our Rockstar Status. Without the funds at a Rockstar's disposal,

however, a motel was not to be had. The best we could do was

$125 for two people per night. The hostel was $15 for thruhikers

($20 for everyone else). Ashland was a pricey town, but it looked fun

as well. Small restaurants dotted the quaint streets, with interesting

shops here and there. The town had avoided the dual dangers of mass

commercialization (a danger from being right off the interstate) and

tourism. A town based on curios and fudge and t-shirt stores,

where every shop was spelled "Shoppe", with plenty of "Ye olde"

signs, was one that was as bad as one filled with McDonald's and

Walmarts. Ashland was really nice and people obviously paid a premium

to live here: The expensive cars seen throughout confirmed this, as did

the prices in the menus posted in front of the restaurants. Separated

from the others, I settled into a steaming shack next to the main drag,

which promised various bits of food. A $4 burrito was surprisingly large,

but also filled with a rather excessive amount of brown rice and little

else. Still, it was nice to sit, filthy and stinking, and watch the

people go by, sipping on the lemonade that I had paired with the

burrito.

As 5 o'clock rolled around, I returned to the hostel to find the others

roaming about. It was open again and I got the grand tour. Internet was

free, though we were supposed to limit our time to 30 minutes at a

stretch. There was a nice sized kitchen for our use and a pleasant

front area with couches and a radio. Women slept in dorm rooms upstairs

and men downstairs. There was also a TV and VCR downstairs. Bunk beds there

were, though fans there not. No air conditioning, no fans. I was sweating

just standing there and did not relish the coming night. Despite the

heat, I spent thirty minutes in a steaming hot shower trying to get clean.

My Achilles still would not wash out and remained the usual light brown

color. With clean clothes and a fresh scent, I pawned off my dirty

clothes to Rye Dog, who was about to do a load of laundry in the hostel's

coin-operated machines, and thus considered my day's work done. Reunited

with Will and Sharon in the upstairs, we now had the usual debate about

where to eat and how to spend the evening. I had seen a brew pub in town

and when young woman looking after the place suggested that it had the

largest nachos we would ever see, we were intrigued. When she added

that the three of us would have trouble finishing one plate of them,

we were hooked. Besides, the Tour de France was going on and we all wanted

to see how Armstrong was progressing in it. A pub was sure to have a

TV.

Shame is something that no thruhiker knows. There are so few expectations of

you that you can't really fail at anything. All you have to do is walk, and

you've already won. You can be as dirty and smelly and foul mouthed as

you want. Most of the time no one is around to see it, and shame is

something needs others around in order to grow. However, in town

there is one thing that will shame a thruhiker, and that is not

cleaning one's plate. We had found the brewpub and I had drunk down

several pints of the most wonderful IPA and Strong Ale that I'd ever

had. The three of us had ordered two plates of nachos, figuring we

could finish them and then order dinner. Thruhikers were supposed to be

able to eat, and we were thruhikers, right? The waitress had to carry

each plate over by itself, a load of two being too much for her to

carry. On a platter the size that turkeys are served on during the

Thanksgiving holiday came a mount of chips, black beans, salsa,

tomatoes, chiles, lettuce, cheese, sour cream, guacamole, cucumber,

red onions, green onions, and grilled chicken. Our second dinner

was in doubt. When the second platter came over, the second dinner

was forgotten, as was any pretense about caring what Lance Armstrong

might or might not be doing. Ninety minutes later, we were licked.

Thrashed soundly and completely. We had devastated the platters, yet

there was still food left on the table. My shirt had come untucked

from my pants, and my pint glass still held beer in it. I looked at

Will sheepishly, hoping he might have a little left in him, might be

able to save our honor. He, too, was done. Sharon was done. We had

brought shame to ourselves and the PCT and had to ask the waitress

to take the platters away.

At the hostel we settled in, meeting the other inhabitants, who were

mostly students at a summer bike mechanic school that was running for the

next few weeks. The Usual Suspects was playing on the VCR

in the downstairs and we huddled around the idiot box, watching the

movie that all my friends characterized as excellent and with a

most surprising ending. Knowing that there had to be a plot

twist that could not be predicted, I understood within 10 minutes

who the bad guy was and what was happening. Perhaps if I had watched

the movie without warnings from my friends, it might have been a

thriller, but now I just waited for it to end. The sunsets and the

stars were much better ways to end the day. Sharon had made a run to

the local corner store to bring us back some ice cream, our appetites

having returned after our failure with the nachos. It always did.

With a full belly, I tried, honestly, to sleep. It wasn't

possible in the heat, and I thrashed about in my top bunk,

wishing that I had drunk a few more pints of beer to help

my sleep. The thick, hot air of the basement was simply too much and

I thought about taking my sleeping pad out into the parking lot,

where it was sure to be cooler. As appealing as Ashland seemed, I

would have greatly preferred a rocky knoll again instead of this soft

bed. Instead of this heavy air and a night of tossing and turning.

Instead of, well, the confines of culture.