The Luxury of Time

Eureka, MT to Bonners Ferry, ID

July 17, 2008

Towns have a certain gravity for those who walk for a hobby, for everything that is missing in the outdoors is here in abundance: Food, water, shelter. Beer. But towns are also repulsive because of all of these things. You can't defeat the gravity until your repulsion is at a maximum. At least normally, for Eureka seemed like a decent place to live, yet I was looking forward to continuing westward to the ocean. Joe was nowhere to be seen when I left in search of breakfast. I picked up a copy of the local paper and headed to Cafe Jax for breakfast. Reading local papers, this one from Missoula, is a lot of fun: You get the basic news, but the local sections show what is going on in the area, what is important to the people, what they do, and where their interests are.

Jax did not make much of first impression. Done up like a 1950s diner, it oozed the sort of tourist trap rubbish that distinguishes places that leach off of others from those that are community gather places. Appearances are the crudest form of observation. I sat in the back booth and a blond woman had a cup of coffee in my hand almost before I sat down, along with an extensive menu featuring omelets and other dishes named after and created by the members, both current and former, of the staff. Looking around, it was clear that at this hour I was the only outsider, unless it has become fashionable in tourist circles to look like grizzled old men. A huge sausage, chili, and cheese omelet came out, adorned with chunky hashbrowns and thick slices of wheat toast. I lingered at my food, spending nearly an hour eating, slowly, methodically. It wasn't haute cuisine, but someone had spent the time to make this for me, animals had died to produce it, crops had been grown, chickens raised. I spent another hour reading the paper, drinking yet more coffee, and talking with the staff and the locals, who took an interest in what I was doing precisely because they had been to many of the places I had just come from.

I had only one more chore to do: Internet. I wandered over to the the library and found it closed. Another ten minutes. Next door was, improbable as it might seem in this cowboy town, an organic health food store. I wandered inside to take a look, for such places are all different. A Safeway in Lakewood is pretty much the same, down to the floor plan, as a Safeway in Salem. No fun going to one. The smell inside was powerful, with a mixture of the bulk herbs and spices, the dark roasted coffee, the incense, this mixture was thick, but not repulsive as a Bath and Body Works at a mall is. I'd rather not repeat the story of why I've spent time in a Bath and Body Work.

Internet didn't take long: Pay a few bills, respond to a couple of emails, check the weather forecast. I picked up an outstanding Pink Lady apple from the health food store and wandered back to the park where the sprinklers had soaked my tarp, but not the gear inside. I spread things out to dry in the sun, while I sat under a tree in the shade. I didn't feel lazy. I just didn't have anything more important to do at that time than sit under a tree in the shade. I lazed away the rest of the morning and around 1 pm my shade was running out. Time to move on. I shouldered my pack and pulled my new hipbelt tight. At least for a second. Maybe less. The plastic buckle that connected the hipbelt to the pack had sheared off. A bit puzzled, I tied the webbing of the hipbelt directly to the pack using a water knot and called it good. Pleased with my engineering, I shouldered the pack again and pulled the hipbelt tight.

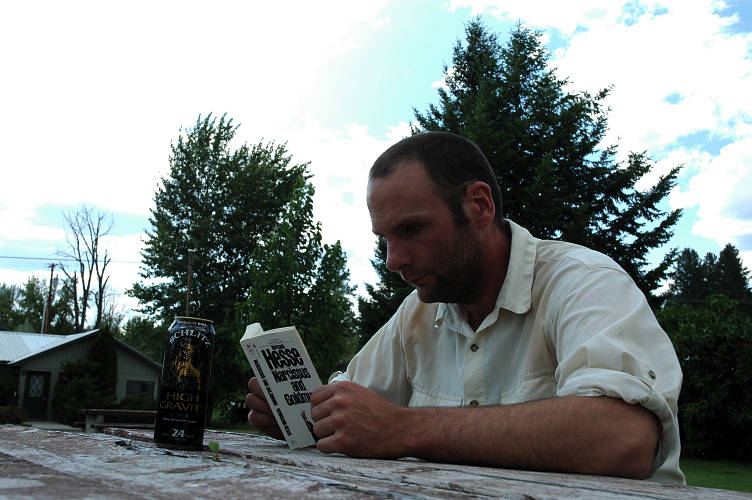

Joe rolled up to the picnic table where I sat drinking an ice cold can of Schlitz VSL, trying to get every last drop of goodness out of it, after finishing his afternoon run. I explained about the pack, about how I had shattered one buckle and then the other, leaving the pack with no hope of hipbelt. The water knot idea would have worked, but what I needed was a new belt altogether. After a few hours of sweet talking a variety of people in different locations, I had finally managed to talk to Brian in Logan about a new pack. He was sending it overnight express and hopefully I could leave town tomorrow. I had the time for things like this to happen and it might be a good sign: I had to explore the town now.

I wandered over to Cafe Jax for dinner and was horrified with what I found. I had now eaten four meals there, but hadn't been to dinner there yet. The tacky interior was covered with white table clothes and bottles of wine on the counter. As I later learned, the daughter of the owner had gone to cooking school in Italy and wanted to have a high end eatery in town to put her skills to use. I should have turned around and run away, but I'm not very bright and so when no one came to seat me I took a spot at one of the many open tables. Eventually someone came over and announced that the special was an all you can eat pasta with choice of sauces. Well, All You Can Eat are the best four words in the English language for a distance hiker. I ordered the alfredo with chicken, figuring it would have maximum calories and fat in it. After 20 minutes it came out and was marginally tasty enough, even though I got something other than what I ordered, to get a second plate. Another thirty minutes passed without the plate showing up. I paid my bill and left, without, for the first time in my life, leaving a tip.

Joe and I talked about the Road and travel and the Vietnam war for an hour. About Mexico and Central America and living with prostitutes in a Panamanian brothel. That was Joe's story, not mine. It was a good story, and one that you don't here everyday, but I can't repeat much of it. My first impressions of Joe had been wrong. Joe talked a lot, but that was because he was used to being alone, was used to having people avoid him or ignore him or otherwise pretend that he was not there, even when he was in front of their eyes. Since I didn't do that, and had had similar experiences, Joe and I had a lot to talk about and this was his opportunity to unload. When I had something to say he really listened, rather than just waiting for his turn to talk. We had dialogue. It was a shame that so many people missed Joe for the simple reason that he was on foot and without a fixed address. Given that he was leaving town in a few days to hitch hike to Canada "...to look at some property", Joe was not without means. He just chose a different way of life, one that was scary and threatening to most householders, one that disregarded what most people found important, one that didn't reduce him to the status of a consumer.

I stuffed my face on the Rachel, an omelet named after, and created by, the main waitress at Cafe Jax, while reading the paper and drinking coffee. I was already on a first name basis with most of the wait staff and several of the locals. They knew of my pack problems and where I was going and where I was from. I wanted to know about them, but I was the oddity in the room and so told my story to anyone brave enough to ask. Joe came and went several times during the three hour coffee session while I waited for the afternoon when my new pack, hopefully, would arrive. I wandered up the road to the video store - internet cafe where I had talked my way into using their phone to take a call from Brian yesterday. I drank yet more coffee and fiddled around the on the internet before settling in and watching a movie called Meet the Robinsons. Like all Disney or Pixar animated movies, it was awful. But the 16 year old girls in the place seemed fascinated by it.

I set out for the post office in the afternoon heat and passed Joe sitting in the windowsill of a business talking to another person, who looked a lot like someone who didn't live indoors much of the time. A beat 1970s Japanese motorcycle was at the curb and I suspected that the sled might have been the man's only other possession. He, too, was former military. The three of us talked for a while in the hot sun before it got too much and I had to move on. I was hoping for the pack, but if it wasn't there I could spend another night in Eureka without too much difficulty.

Joe was nowhere to be seen when I got back to the city park with two cans of beer and no pack. The town had definitely grown on me. Even the teens on their souped up quads, exhaust pipes blasting, racing up and down the street. Since they would draw the attention of the law if they drove on the street much, they settled for ripping down a 100 yard section of asphalt off to the side of the main drag. One in particular had a flashy neon green helmet with a plastic mohawk glued onto the top of it. I was going to be in town another night and didn't feel at all bad about it. I paid $5 to get the key to the bathroom and took a shower in my clothes, giving them, and me, a good rinsing. I hung them up to dry and then walked around the camping area, shirtless in the warm air, wearing only my draws, beer can in hand and without a care in the world.

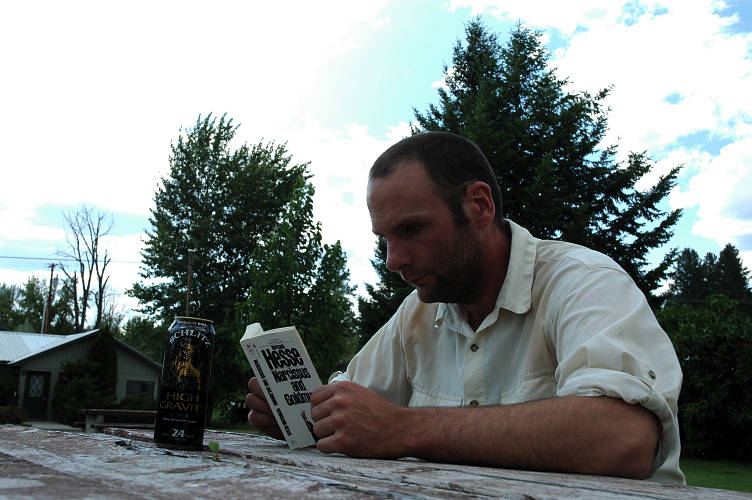

I sat in one place and after a few minutes picked up and moved to the a sunnier spot. Then to the shade. Then to the picnic table. Back to the grass. I put my clothes back on and went back to reading Narcissus and Goldmund. I had read it before and loved it, but was getting a new perspective this time around. Hesse has a way of doing that. Although he had never struck out on a long journey, or tramped around, or been homeless for any appreciable segment of time, he was getting a lot of the details right. The feelings, the evolution of thought, these were things that he seemed to have figured out just by thinking about them. He missed some of the more important, more subtle issues, but that is to be expected. Joe strolled into camp after his afternoon run and I put my book away. I can read at any time, but people live in the present and I had taken a liking to talking with Joe.

We were in the middle of discussing VA benefits when a portly, bearded, sun glass wearing thirty something rode up on a modified mountain bike with panniers. Long distance cyclists are rarely overweight, but this one was. He had signed on to a guided mountain bike ride down through the Canadian Rockies and was then planning on going his own way to Mexico along the Continental Divide. After setting up his tent, he broke out his tale of woe, which seemed mostly to involve how awful the other riders were and how annoyed he was with them. Joe and I listened for a while and then left him to his complaints.

I made my way over to a small pizza joint across from Jax called Grandma Tina's. Although it was hot inside, Grandma herself made me a special salad and an excellent pizza for dinner and I sat inside watching television for the first time in months. The news was on, or rather wasn't, because the TV was dialed into Fox News. I ate and talked with Grandma. Just talking, you see. Spending time. Spending my time and her time and time overall. I had the luxury to do things like this. Just talk with a random stranger. After last night's experience it was nice to be taken care of.

Joe and I were back talking at the picnic table when the porcine rider returned from where ever he went to. He was mildly drunk, but was getting drunker. He was a high school teacher from San Diego, but failed to recognize that one of the local youths was 13 instead of 19. And that he wasn't carrying a gun in his pants, but rather was just walking in the style that youths seem to these days. The youth probably wasn't used to be asked by a random, drunk stranger if he was "...packing heat in your pants." and seemed a bit nervous around the cyclist. I shooed the youth away, not that it took much doing. As the cyclist got drunker he got more obscene in his references to the others in the group that he had left that day. He even included sound effects. He changed topics and seemed to want to find a hippy prostitute with hairy legs who might have some weed for him. He hadn't seen any in town. Joe left in disgust for his tent, but I was in the tarp and couldn't run anywhere. I told him to go away and then ignored him by reading. His stories continued. I told him to try the bar in town, but he said he was afraid to go to inside. I told him to go somewhere else, sprinkling in a few F-bombs for emphasis, but that didn't go through either. He wanted me to read to him from Hesse. A few more F-bombs. His speech slurred more and at one point I thought he was going to fall off of the picnic table, which would have been for the best. I stopped talking or responding to him and after five minutes of his rambling and my silence, he came out with "So, do ya wan me go way?" Another few F-bombs and he went off to bother the high school kids hanging out on the other side of the river.

I drank a few more beers while reading Narcissus and Goldmund under my tarp and watching the fleshy drunk stumble around the park and the river area. I couldn't relate to people like him. I liked good, happy drunks. The fact that he was getting loaded on orange flavored pretend hefeweizen was a really bad sign that I should have picked up on, but since I didn't like him from the very start there wasn't much time lost in appreciating his unique qualities. He had drunk five beers. If you can't hold you liquor, and five sissygirl beers in a 250 pound, 5'8" man means you can't, then you should drink something else or at least hide your shame in private. I turned off my light around midnight and went to sleep. The last I saw of the lout was when he almost fell in to the river. I wasn't sure if I would have hauled him out or just let him float down to Lake Koocanusa and get stuck in the turbines of the dam.

I sat in Cafe Jax stuffing my face with another big omelet (the Chico) and read the paper. A few locals teased me about still being in town, about having a secret love that I could yet leave, about settling down here and "..gettin' honest.". I had only been in town for a couple of days and it already was feeling like home. Joe joined me for part of my three hour coffee and paper session, coming and going on various errands that he wanted to run. He was leaving tomorrow for Canada to buy, possibly, a parcel of land that he had had his eye on for a while and needed to tie up loose ends in town before hitch hiking north into Alberta. Around 11 I picked up the old pack and wandered over to the PO which, being Saturday, had just opened. I stuffed the old pack into the same box, taped it, and sent it back to Brian in Logan. The new pack was definitely bigger, beefier, and heavier. I'd be able to use the extra space when crossing the Cascades, but for now I had a lot of empty room in the pack. It was hot out, so I stopped in Corner Video and interneted for a while in the air conditioning. And drank more coffee and listened in on the conversations the teenage girls were having about this boy and that girl. It was too hot to go anywhere for a few hours and I wasn't in much of a hurry. I went over to Jax for some lunch and ran in to Joe, who was on his way to the far side of town to meet with some other vets. We said our goodbyes quickly and he was gone, another memory from the road.

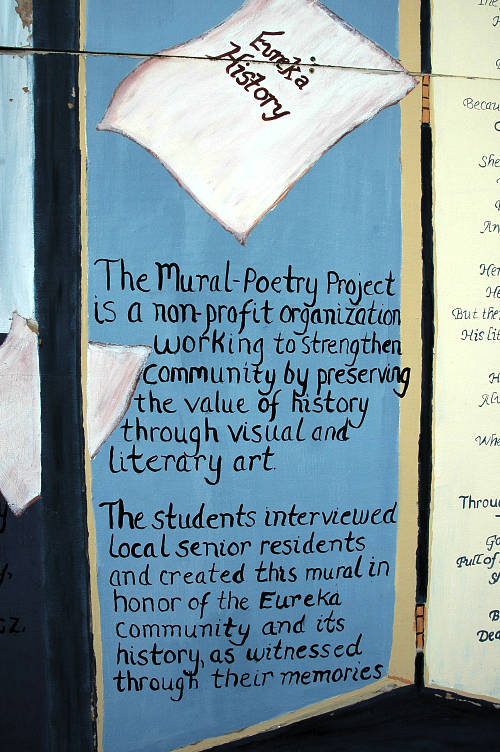

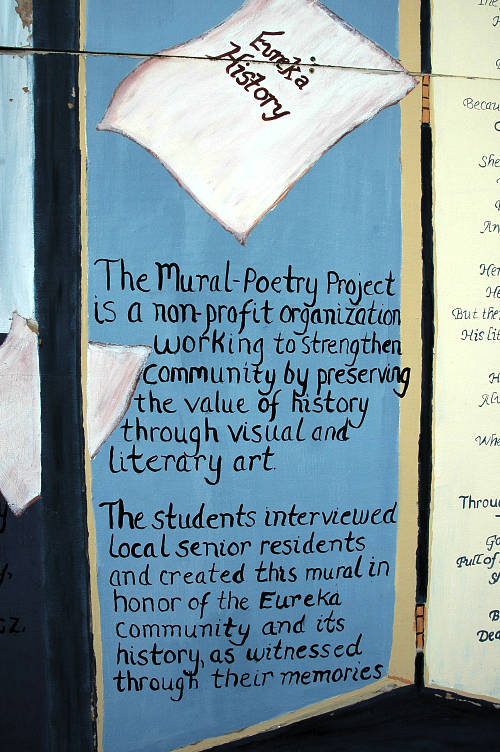

Rachel sent out a jumbo huckleberry shake on the house as a goodbye present for me. The thick ice cream was popping with last season's huckleberries, picked by the gallon no doubt and frozen for use in the winter and spring months when local fruit is non-existent. Like Polebridge, there was a distinct sense of community in Eureka. People knew each other. They knew each others kids. They knew what they did. They knew their interests. And, more importantly, they treated each other as other members of a community, rather than as taxpayer units that it was best to avoid getting to know, lest you have to deal with their problems. I didn't even know the names of the people who lived in the apartment next to me in Lakewood. Like Polebridge, Eureka was an actual town, rather than just a place where people happened to live.

I went back to camp and declared it to be too hot to go anywhere on foot. Normally this is an excuse to drink a few cans of beer, but I wanted to walk out of town tonight and if I started getting loaded, I'd end up taking a nap under a tree and staying the night. The cyclist's tent was gone and I wasn't upset at having missed him leave. I packed up my gear slowly and then sat in the shade doing nothing. The luxury of time. I wrote in my journal and looked at maps and dreamed up other adventures and thought about old friends I hadn't seen in a long time and read bits of Hesse and wondered what people back home were doing and pondered the nature of society. It was nice having the time and inclination to do such things, but when 4 pm rolled around I declared walking season to be open once more. I shouldered my pack and left my shade for the railroad tracks out of town.

It felt good to be on the move once more, to be roaming about free and happy like a leaf on the wind instead of being fixed to one place. Community, true community, was becoming more important to me as I grew older, but so was the freedom to see new things and meet new people and spend time on my own. The railroad tracks followed the Tobacco river out of town. A few locals were floating down the river in inner tubes. Sometimes my stupidity truly shocks me: The river flows right into Lake Koocanusa, where I was heading. Rather than walking, I could have taken the river! The old grade took me past farms and field, horses and cows, sometimes in the hot sun and other times in the shade of thick vegetation.

After an hour of walking I reached passed under the highway and left the tracks for a trail through the woods along the bluffs that rimmed the lake. Lake Koocanusa is formed by Libby Dam on the Kootenai River and backs up water for eighty miles all the way into Canada. I needed to cross it via a bridge to the south which could only be reached by road walking. But for now I alternated woods and fields, views of the lake with the damp coolness of the deep forest.

After nearly three hours I dropped down from the bluffs and reached a large parking lot for car campers and boaters known as Mariners Heaven. The guidebook listed a distance of 3.6 miles from Eureka to here, but it was more like 7.5. I had heard rumors that there was a new trail in the area to keep hikers off the road, but didn't see it right away. I took the first thing that looked right and ended up in the backyard of a luxury vacation home instead. I picked my way through a few other yards and ended up at the highway.

Normally road walking is something to be avoided. The hard surface hurts your feet and ankles and knees. The reflected sun burns your skin. The cars racing by cloud you in dust and choke your lungs with exhaust. Assuming, of course, that they don't veer off their lane by a foot and clip you. But state highway 37 was nearly deserted and a car passed me only every few minutes, with a couple of good 10 minutes stretches without any vehicles. The sun was low in the sky, giving me plenty of shade to work with. The views down to the lake and the mountains, my mountains, on the other side were sublime. I found myself curiously enjoying being on the road. It wasn't a feeling like being in the deep forest or high mountains or open desert or any wild place. What I had was a feeling of pure freedom, of complete unrestrained life that was very powerful. I took a seat by the side of the road where I could see the blue lake. A few cars passed and I wondered what they thought of me, sitting by the side of the road looking at the lake. Would one of my former students even recognize me sitting on the side of the road with a pack next to me and clearly without a home for the night? Would they see their former teacher, his button down shirts and dress slacks exchanged for stretchy nylon, or would they just see someone to be ignored, avoided, laughed at, pitied.

It was beginning to get dark and I needed a place to stay. The safe thing to do would have been to jungle up in the woods next to me and spent a viewless night under the canopy of trees. But I thought that there might be something better out there, that the lake might hold a secluded camp site on the water. At the junction with the bridge, I walked out onto the steel expanse to get a better view of the eastern shore. There it was. A perfect, wide, flat rock right next to the water. Drivers going west couldn't see it, and those coming east would have to have very sharp eyes. I didn't know who managed the land, but I suspected it was the Corps of Engineers, and hence I would be on public land. I dropped down the talus field, picked my way through a few trees, and came out to the lakeshore and my home for the night.

I filtered water out of the lake and set up camp, boiling up a feast of Lipton's Cheddar and Broccoli Rice with olive oil. I never eat the stuff at home, but here, but the lakeshore, it was culinary perfection. A few cars drove over the bridge, but I mostly had the place to myself and enjoyed the thought that for tonight, and tonight only, I'd have the greatest bedroom in the world at no cost. Somewhere in the High Sierra some PCT hiker was thinking the same thing. A CDT hiker in the San Juan Mountains of Colorado had the same idea and this exact moment. An AT hiker on top of Cold Mountain in Virginia was pondering the same thing. There isn't a resort anywhere in the world where you can pay for a room and get the same quality of experience that you can on public land for free. It isn't hard to figure out why: Resorts insulate you from the natural world; they give you only a partial experience. I was sleeping in the open air for their was no reason to ruin the starshow by putting something overhead. There was no threat of rain, there were no noisy neighbors, and I would truly leave no trace of my presence once I left in the morning. The wind was pleasantly cool as it caressed me, sitting on my rock, watching the stars and the dancing blackness of the lake. I wanted nothing else.

I sat on my rock in the cold morning air, the pale sun bringing just a hint of warmth to my face, and drank the steaming tea from my cook pot. A good, basic black tea direct from China, complete with honey-cocoa notes. The hot liquid warmed my insides as I sat there, watching the bridge and the lake begin to dance in the morning light. I had slept well on the rock and was refreshed. The PNT went up Mount Webb, but I had no intention of following it up an overgrown trail that every distance hiker for the last few years has cursed. I had a different plan in mind, one that I had come up with as I sat in Eureka: Forest Service road to where the PNT comes back in, then rumble up to Mount Henry for the night.

I packed and set out, lingering along the bridge to enjoy the early morning views and the temperate air. It was a perfect morning for a stroll and there were few cars on the road at this early hour. I crossed to the other side and started north on the highway, for my forest service road was about 3 miles up it. The road steadily gained elevation, providing me with great views down to the lake, to Eureka, and to the mountains I had come from. As I neared my junction, a large white SUV with lights on top drove toward me, slowed, and pulled over to the side of the road: It was the border patrol. The officer behind the wheel put his game face on and we began our dance.

Jack:"Where's your rig?"

Me:"I'm on foot."

Jack:"That's why I stopped you. We don't get many people on foot around here. Where are you coming from?"

Me:"I came out of Eureka yesterday. I slept down by the bridge."

Jack:"Where you heading?"

Me:"Mount Henry, then Bonners Ferry."

Jack:"Got ID on you?"

Me:"Yes."

Jack:"I need to see it since you're this close to the border."

Given that I was probably 30 miles from the border on foot, this didn't seem like much of a reason. We continued our dance as he went through his Joe Friday routine. He'd ask me a question, then ask it again in a few minutes to see if I gave the same answers. He'd tell me something I hadn't told him and wait for me to correct him on it. He'd be my friend and offer advice on the area, then come back around with a stern question. He called my drivers license number into the office and we waited as he went through the interrogation techniques he learned at Criminals Be Dumb school. I corrected him a third time as to where I was from and a fourth time for where I was going. When he got the all clear from the office he told me I could go, but that now he knew where to get a hold of me if he needed to. I had to ask him directly for my license back and he seemed a bit put out that I wasn't nervous enough to forget about it. I packed my stuff back off and set off. Just as I left he asked me one last time where I had spent the night.

I didn't understand why I had been stopped or interrogated. I wasn't close to the border and he never even asked me if I was a US citizen or not. If he was a cop, it would have been clear what to do and what my rights were. But the border patrol was different. At the border your rights seem to disappear into the fat air surrounding the border patrol or ICE agents. Just ask anyone with olive skin. But I was fairly far from the border, and walking toward it, not away from it. How far did the border patrol's power extend? What would happen if I said, "I have answered all your questions. You have no probably cause to detain me any longer. If you do, arrest me. Otherwise, I will be on my way." There is no federal law requiring citizens to carry identification, I had broken no law, and I did not appear to be about to break any laws. But, the border patrol was different. Local cops have to answer to local citizens. But the border patrol? I fumed for a while as I walked up my forest service road, but as I gained altitude I slowly let the encounter with the border agent fade my memory, even his ominous warning about coming to get me if need be.

The road I was on was skirting around the side of Mount Webb, perhaps 800 feet below its rounded summit. The mountains here were not like the Cascades or the Olympics. They were not alpine. Rather, they were soft and rounded. These were not mountains to go climbing in. They were mountains to be lived in. Although I was on a road, no cars passed me nor was there much evidence of cars having been through the area in the last few days. The PNT came back to join me from its excursion up Mount Webb and along a short bushwhack, to a road, to another road, and then to me. Despite my encounter with a border agent looking for a case, I was pleased with my route decision. The heat of the day grew as I wound up the switchbacking road toward my trail head. I found a good water source coming down from the hillsides above me and sat in the shade for an hour to lunch and hydrate, for I had a long climb ahead of me to reach Mount Henry and a full pack on my back.

At the trailhead I found two trucks parked, but no humans. This would be my first long climb since my difficulties on Thoma and I hoped my theory of chest compression was correct. I gather a liter and half of water, sure that I would find more, and started the climb into the woods. Sweat formed on my brown, and I breathed deep, but I kept a regular pace and switchbacked up the mountain side, enjoying the distant views and beargrass along the way. My theory was right: I was back in normal form once again. My trail reached the top of the face that it had been climbing and I was presented with a curious description in the guidebook and no markers for the critical trail junction I was looking for. Even worse, there wasn't a trail junction. I hunted one way, then another, and the, returned to my first, best guess. I finally spotted the thin trailway, obscured under a blown down tree. So this was the start of the Mount Henry National Recreation Trail. Not a good sign.

The trail dropped down from the ridge into a deep, dark forest where the air was hot, stagnant, suffocating. Mosquitoes, flies, gnats, other bugs seemed to infest the place, for I was hiking through what appeared to be a swamp at times. The trail was clearly not maintained, at least regularly, for I had to battle through deadfall after deadfall after deadfall. Some were complicated and extensive enough that I had to spend five minutes negotiating them. Branches would snap back and hit me. Sap stuck to my clothes and skin and matted the hair on my forearms. A misjudged step and a sharp stick would jab me.

I was sweating profusely and was low on water, which made the swamp all the worse. There was water here, but very little of it useable. I was counting on a lake on my map to refill my supply, but one look at it convinced me to move onward. It was stagnant and I could smell the stench coming off it from some distance away. Even with a filter I wouldn't trust the source. I had half a liter left when I started the climb away from the lake and the swamp and back to the higher country, hoping to reach, and find, a spring in an hour or two.

Once above the lowlands the trail improved and I even got an occasional view. I stopped to drink some of my water and rest and to try not to think about how hot it was or how little water I had left. The pine forest was open enough not to be oppressive, but I was tiring rapidly. Without water my body was beginning to wear out. It took several hours, but I reached the base of the climb to Mount Henry, complete with a view to the summit and the ranger cabin on top.

I was moving slowly in the heat, my dehydrated body still listened to my mind when it told it to go forward, but it wasn't happy. I intersected various trails without markings and made my best guesses as to direction. Sometimes I was on a trail, other times on a game path. But I gained elevation and, hopefully, was making progress toward a spring marked on the map. I started to wonder what I would do if I couldn't find it. It was easily five or six miles to the next water source on my map and, in my current condition, that meant another three or four hours without water. I staggered up the hill, sniffing the air for any hint of moisture, scanning each gully for a sign of the spring. And then it just appeared at my feet.

A little puddle. Next to it was a halfassed attempt to cover up the source with a wood lid, but inside the water was full of twigs and needles and dead bugs. I didn't especially care and set to filtering 2.5 liters right away. The five minutes of waiting for gravity to draw the water through seemed an eternity. I chugged a liter, and then a second, and started more filtering as I lay against a shady tree resting. It is the simple things that are the most luxurious: Shade and water. What is a Gucci whatever compared to shade and water on a hot day?

I spent more than an hour drinking water, eating dinner, and resting at the spring. My body accepted the water with greed and I slowly began to come back from the exertions of the day. The dry, hot air sucked the moisture off my clothing and skin like I was in the Mojave and by the time I started up the last few hundred feet to the ranger cabin on top I was dry and felt fine. I broke through the tree line as the trailed turned from dug-forest floor to rock and dirt. I wound around and intersected the trail I'd take down tomorrow, made a right turn, and was on the summit within a few minutes, panting at the effort. I had covered about 25 miles today with a lot of elevation gain, but I was done with plenty of daylight left to enjoy my rewards.

I climbed to the ranger cabin and found it open and a bit run down, but quite acceptable considering the high winds that were raging on the summit. I dropped my pack inside amidst broken glass and mouse turds and walked around the outside of the cabin to admire the views. Much like Thoma, only without the craggy peaks of Glacier National Park. More like the Smokys, I thought, than the Rockies. The views were of gentle mountains, covered with green trees and pleasant. It wasn't the mountains that were impressive here. Rather, it was the sense of space. It truly felt like I was seeing forever, for hundreds of miles, into several states, into another country.

On the whole, I wasn't sure if the effort required to get here was worth the prize on top. It was certainly beautiful here, but it wasn't stunning, jaw dropping, awe inspiring, or otherwise sensational. It was pleasant. But the lack of water, the heat, the swamp, and the hundred, perhaps, blowdowns balanced that out, and maybe more. If this was, according to the PNT guidebook, a "10 Best" location, the future was not bright. If I had carried more water, say another two liters, I would enjoyed the end more. But I only had 2.5 liters total capacity and had hauled two liters up from the trailhead.

I wandered around the outside, recovering and enjoying the fading light, for thirty minutes before going back inside to make my bed for the night. There was a makeshift bunk with random junk that the rangers had left. Instead, I grabbed a broom I found in a corner and swept the floor clean of turds and broken glass. The rangers didn't seem to be maintaining their cabin especially well. Outside I had found numerous canisters of trash that had been there for quite some time. As in years.

My chores done, I went back outside with my radio to watch the evening show and to try see what was coming through the air. I had been powerfully moved on Thoma by Midnight Train to Georgia and hoped for a similar experience up here. A country station was the first thing I got. Brad Paisley crooned about how he was "still a guy..." even though he walked his girlfriend sissy dog. Not quite what I was looking for, but when a tuba riff came into the song, I got a lot more interested. I had never heard a tuba on a country song, any song. But there it was. All five seconds of it, and then the song ended. Mount Henry was casting its shadow back to the east, where I had come from, giving me one of my favorite views in the outdoors. You've got to be high to see it.

The sun was setting and i was dry and hydrated and feeling fine once again. The work required to get here seemed more justified now than when I first rolled up and I sat in the orange light writing in my journal and listening to crunchy rock and roll from a Calgary radio station. The wind was ripping along, which made writing hard but felt good against my skin. Last night I slept in one of the most perfect bedrooms I'd ever been in. Tonight, I realized, I was there once again. There wasn't a luxury hotel anywhere in the world, in any city, that was better, or could even match, what I had up here.

There are plenty of places that have balconies to watch the sun rise or the sun set. But there wasn't a luxury resort anywhere that had a view for hundreds of miles with almost no sign of man anywhere. There wasn't a posh hotel that had this much open air around it, where you could absorb the extensiveness of the land and see what the land might have been like a few hundred years ago. I liked civilization and progress just fine: After all, I was going to be sleeping in something made for lazy rangers. But Steve McQueen was right: I, too, would rather wake up in the middle of nowhere than in any city on earth.

I flipped through the dial on my radio, another one of mankind's more clever inventions, and found a blues station coming somewhere out of Canada. The blues helps you think precisely because it forces you to feel: Rather than thinking with part of your self, it is better to think with all of it. Yes, I liked civilization and I like progress. I like things that contribute to humanity and advance quality of life. I don't like things that get in the way. Things like television and marketing and advertising and politicians and shopping malls and suburbs and fast food joints and text messages and Republicans and Jimmy Choo shoes and celebrities and celebrity magazines and eggplant and paper shuffling jobs and Democrats and SUVs.

These things get in the way. They dehumanize us. They reduce us to the gutter and make us only consumers: Produce some wealth for someone else, then spend your meager earnings on crap you don't need and don't really want but have been raised to believe you do. The thing that makes America great is that you've got a choice here. You don't have to live like a consumer. You can turn off your TV. You can get a real education (meaning a library card). You can make choices about how you live your life, about how you spend your time. What is sad is that we so consistently make bad choices. We choose the worse option over the better through our own ignorance. In most of the world your path is laid out for you at birth and there is little you can do to alter it.

Don't think so? Just ask the 80% of the citizens of our planet who live on less than $10 a day. Ask someone born in Chad. Or Syria. Or Nepal. Or Cambodia. Or Mongolia. Or Albania. But what did I know? I was sitting on the balcony of a broken down ranger cabin filled with mouse droppings (and probably hantavirus) all alone and with nothing to do but complain about modern society and to watch the fabulous sunset. Maybe Jimmy Choo shoes were really comfortable and would make me feel better about the world I lived in. Maybe if I wanted them I could focus my attention on them, on how to get them, on what to wear with them when I got them, on what celebrities were wearing them, on which of my friends already had them. Maybe if I could do that, I'd be even happier than I was right now watching the world glow orange and red and pink and purple, and all the colors of a hydrogen bomb explosion. If I could do that, maybe I wouldn't think so much about what was wrong in the world and in our society.

I sat on the rotting balcony outside in the pale early morning sun and drank my tea, enjoying the soft views of the valleys and mountains stretching out to the west. Parts had been logged over after burn which must have happened a decade or two ago, for the growth was still short and fuzzy. In the far distance I could see a small settlement of some sort with a road snaking toward it, barely visible in the morning shine. It was nice up here. Worthy of spending another day just sitting on the balcony doing nothing, worthy of time. It was a good place to think.

I hiked off Mount Henry and began the descent toward the valley below. The burn-logged area I had seen from up high soon became my present reality and I struggled at times to follow the trail. The track had been re-cut after the fire, but not well, for there were trees growing up through it or close enough to it to obscure the pathway. I could follow the trail by signs that I was used to looking for and made it through the worst stretches without getting too lost. But this was definitely not a trail for a hiker new at routefinding and in a few years, say five, the trail will be lost to the growing forest if something isn't done. Then it will become a locals-only trail.

The burn had opened the forest and the views were grand the entire way down. During a rest break I flipped through my maps and saw that the valley below me was called The Yaak and that it sat below the ridgeline that the PNT would run eventually. A long, forested, waterless, trail-less ridgeline. At least when I would be on that ridgeline when I wasn't walking roads to get to it. I didn't much like that idea.

The trail faded in and out as it began a much steeper descent than before, dropping quickly down through a sequence of broad gullies. As I lost elevation I began to encounter more and more blowdowns, though not on the same scale as yesterday. Because of the topography and the weather, blowdowns are a normal state of affairs in the area. The pine beetle infestation has weakened or killed many trees and over the winter many of these trees will come down. Locals will cut them out eventually, but if the trail isn't used extensively by them it can be years before this happens.

I dropped down to a creek where there was a trail junction. To the right led a climb up over a hill and then down to a road. To the left led a well built trail leading down through the woods to the same road. Why the PNT went over the hill was unclear to me, so I took the nicely built trail down through the woods. As a reward, I ran into a family out for a day hike to the large, multilevel waterfall that was a quarter mile down the trail. I stopped for a rest by the waterfall, enjoying the cool spray, and read over my maps, pondering a route different than the one taken by the PNT.

I had plenty of time to contemplate my route choices for the next few days on the walk down through the woods. It was shady and cool and the view of the river was soothing after so much sunlight and openness on Mount Henry, and especially after yesterday's thirstfest on the ascent. I could think more soberly, more calmly down here in the forest than I had in the open air of Mount Henry after a long, hot day of work. A man carrying a massive pistol on his belt, with a huge external frame backpack, a dog, and two kids broke my train of thought on the properties of causality. I stopped to chat with them for a while. They, too, were on their way out. They lived down in Yaak and liked to come camping in the area, the father bringing his sons to the places where his father brought him. The only thing that had changed in the area, he said, was that more people were coming to the mountains. I told them about my trip so far and the night I had spent on the top of Mount Henry, then pushed on to the trailhead and the road, the hot searing road.

The gravel forest service road that I was walking had little shade and I was quickly sweating hard after the coolness of the forest below Mount Henry. A few trucks drove by and dusted me, increasing my discomfort and parching my throat. It was hot, I thought. Really hot. I thought about how hot it was, but oddly enough I didn't think about air conditioning or sitting on a couch drinking a cold beer or what is was like in Patagonia at this moment. The heat was uncomfortable, but it wasn't driving me anywhere. It was what it was. My gravel road ended and I picked up a paved road that led me to the Yaak River. I crossed the bridge and then dropped off the other side, scampering down to the river's bank. No one was around, so I dropped my pack and waded into the icy water for a bath and a swim. The water was bracing and it quickly rejuvenated me, making me feel strong and powerful once again. I clambered out of the water and tossed my now clean, at least clean enough for me, clothes onto the bank, then swam some more in the river.

I put my draws back on and sat in the sun looking at my maps and plotting a future course. I didn't have a lot of faith in the route that the PNT was taking through the area. There was a lot of road walking to get to limited trail segments, that led to more road walking to get to bushwhacks. Then, I could road walk some more to get to a hot and dry ridgeline for a little more bushwhacking, which would lead to severe navigational challenges fighting yet more bush. If I survived all that, I could then hitch hike 20 miles into Bonners Ferry, then hitch 20 miles back for some more bushwhacking. This didn't seem to be a very good bargain. Instead, i thought, I'll do some road walking, but go directly to Bonners Ferry. The fact that I had no maps for Idaho didn't bother me: Something would work out and if it didn't, I had enough time on my hands to fix things.

My route to Bonners Ferry was direct and, though it involved all roads, it would have plenty of water and I could see how people in the area lived. Moreover, I would only be on paved, busy roads for a stretch today and a little tomorrow. I would then be off my maps and navigating by hope, but at the worst I would have to walk ten miles or so along US 2. I didn't like the idea of that very much, but it was a worst case and might not happen. Feeling like it was time to get moving, I put my clothes back on, shouldered my pack, and stumbled out into the searing heat of mid-afternooon.

I passed the road intersection where the PNT split off to the north and continued on Yaak River road. The heat was still immense and I quickly began to fall from the heights of euphoria that my swim had brought me to. My feet began to feel the heat of the road through the rubber shoes of my trail runners. Sweat dripped off of me in buckets. There was little shade, and what shade there was only seemed to last for a few feet, hardly long enough to cool off. An hour and a half into my walk a woman with four kids in a battered Volkswagen pulled over to see if I needed I ride. I told her I was trying to get to Bonners Ferry on foot and she seemed to understand this. It wasn't the Bonners Ferry part that was important to me. She smiled and told me it wasn't much more than another two hours to Yaak and then sped off. I continued my slow trudge in the heat.

I was limping and massively dehydrated by the time I reached town, which consisted of two bars, one store, and no churches. Just the right ratio for Montana, i thought. I dropped my pack on the front porch and strolled into the store, soaked in sweat and looking beat. The woman inside smiled, but it was clear that I wasn't an unusual sight in the store. I bought two liters of various drinks and then went back to the shade on the front porch. I watched people come and go from the bars, an odd mixture of tourists (what was there to see here?) and construction workers. The tourists pink and wearing shorts, they would go to the store sniff, then go into the bar and emerge a few minutes later. The construction workers headed right into the store and would come out with cans of strong beer in hand. It was too hot for me to be drinking beer. I laughed at what my friends back home would think of that. I got another liter of Gatorade and went back to my stoop for another thirty minutes of rest.

I rested for an hour in the shade and then began another hot slog down the paved road. It was 6:30 when I left the store and all traffic on the road had ceased. It was still blazing hot and I sweated out all that I had taken in during my rest. My feet were aching and I was chaffing hard from the continuous sweating. I tried to appreciate what was around me, but increasingly I focused on how much I was suffering. It was for the best that I reached the campground I had marked on my map as a stopping point for the day. Another 25 miles, just as hard, if not harder, than the day before, even though I had almost no elevation gain.

I stumbled into the campground and didn't see the host anywhere. I was too tired to try to bargain for a free night, so I simply walked to the back of the camping area and put up my tarp on the hard packed platform. I guzzled as much water as I could as I cooked and ate dinner in a futile effort to replenish what my body had lost during the day. I gradually felt better, but when I realized that I hadn't gone to the bathroom since the morning, I knew that tomorrow was not going to be good. I poured all the water I could in to me, then turned in for the night. I was too tired to think and the environment around me wasn't powerful enough to overcome my body's aching.

"Do you have a pay stub?" I had almost made it out without paying a cent to camp for the night on my land. I woke up early, made tea and ate breakfast and packed my gear. I had just put my pack on my back when the campground host sauntered up, making his rounds at the earlier-than-usual hour of 7 am. I thought for a moment and decided that honesty was the best approach here. I told him my story, that I was hiking from the Rockies to the Pacific, that I had come in on foot and couldn't find a hiker-biker campsite, nor had I seen him when I came in."You've got no car?" I shook my head and this brought a smile to his face. "Don't worry about the site." We talked for a while about my trip and he told me a little about himself. He was a self-described former hippie who had come out West in the 70s and never left. He lived out of his trailer, pulled by his truck, bedding down in national forest campgrounds as the host during the summer and headed south in the winter. He understood what I was doing. I wasn't homeless or a vagrant in his eyes, and I appreciated that. I wasn't dangerous or someone to be feared or watched. He walked me to the road and we shook hands in parting.

It was still cold enough that I could see my breath as I strolled down the still quiet road, bereft of cars. It was as if I owned the entire structure myself, that there was no one else around, here or anywhere. I felt surprisingly good after the beating I had taken yesterday at the hands of the sun and resolved to drink as much water as I could today to try to recover yet more. I had only a few miles to walk down the paved road before I reached the intersection with FS Road 435, called Spread Creek Road. Towering above me was Northwest Peak, its fire lookout visible from down here. The PNT went up there. I would skirt around it on my own path.

It was clear from the very start that Spread Creek didn't see a lot of traffic: There was grass growing in a strip in the middle, which meant it was rarely graded. The road gained elevation steadily, but not brutally, and I enjoyed the ease with which I was able to travel through the land. The only difference between the road and a trail was that this road was nice and wide. There were no vehicles, nor had any passed me on the paved Yaak River road in the morning. I stopped for water and rest occasionally, but the 3000 feet of elevation gain to the pass at the top of the road.

The PNT came in from the side, on a brushy, non-maintained trail and left via a muddy track, heading for Canuck Pass. I was keeping to my trail. I sat and admired the few views that I had, for mist was rolling in and out of the area, obscuring the vistas that were probably there. On the other side of the pass the road became impassable for normal cars, but a Jeep could probably have made it through.

Oddly enough, just below the heavily rutted section the road became paved. And not broken up pavement, but honest black top that you could play a respectable game of stickball on. I wasn't sure what county land commissioner thought that it was a good idea to pave this one segment, and not the one I had come up, but I would have liked to think that he had an assistant named Sancho. I could see Canuck Pass a half mile away. The PNT was up above me, thrashing along the ridgeline perhaps 200 feet higher, beating through the trees and brush. I enjoyed the calm walk along the paved road and enjoyed the same views. I crossed the Montana-Idaho border and paused for a photo.

I reached Canuck Pass and had a seat to enjoy the Smoky Mountains-esque view that presented itself. It was pleasant, restful, relaxing. But not, as I had observed before, jaw dropping. Any one setting out on the PNT for the views, I thought, was going to be in for a disappointment. I looked out on the foggy valleys and perceived them not in a comparative manner. Not in a ranking manner. I did not think "These mountains are nothing in comparison to the Northern Coast Range or the Olympics or the Himalayas. They are not worthy of my attention because there is something better out there." I did not think this as I sat on a rock on the side of the road and ate a Snickers bar. It was true that they were not the classic image of mountains that we have. They were not sharp and brutal and glaciated. But they were alluring. They brought you into them with a sense of mystery and emptiness. I couldn't take a picture of, I could not record, the quality of the Land that was drawing me in.

I wandered down the other side of the pass, eschewing the PNT and its brushy, dry ridge for the road and an unknown run into Bonners Ferry. My map showed only that this road would eventually intersect US 2, which would, I knew, get me into Bonners Ferry. How I would get out was a problem for another day. I rumbled down the road, losing elevation slowly, gradually. The pavement ended as curiously as it began, returning to gravel, though graded to a high standard. A truck passed me on the way down, the first vehicle I had seen during the day, despite having spent all of it on a road.

Several hours of pleasant walking brought me down to the valley bottom where I found a nice, cleared area where people had camped before. I had seen a few other places like this on the walk down, where trucks with trailers or cars with tents were stopped. A small community was living in the national forest for free, with little oversight or regulation except for what was considered common decency. A little metal sign tacked to a tree in my spot reminded dwellers to pick up after themselves, and indeed the campsite was clean except for the normal detritus of cigarette butts and candy wrappers, items small enough not to be noticed by people in trucks. I stopped early, at 5 pm, having covered another 25 miles. I estimated that I had another 9 miles to go to US 2, but didn't want to out walk the national forest, for I needed to spend the night somewhere and sleeping in a farmers field didn't sound appealing.

I cooked Broccoli and Cheddar Rice and Sauce again for dinner and then laid around writing in my journal and reading Hesse. But I put these diversions aside after a few hours and instead just sat with my back against a tree and thought about my trip. I seemed to be rather actively skirting the PNT, skipping it when it seemed like it would be more of a pain than it was worth. I was on the anti-thru hike, not following a well defined path through the woods or mountains or desert. I was, instead, on something more akin to a pilgrimage, but I didn't know for what or to where. Instead of having a definite route in mind, I instead had only time and a general direction to follow: The setting sun. The freedom to decide where to go was appealing to me more and more, even if it seemed strange that roads were providing much of the treadway for me. That didn't matter, though part of me thought that it should. But there are plenty of lines on a map for people to follow. I've followed them and I was sure that I would follow some again in the future. Right now, though, the freedom of the unknown was intoxicating me. I didn't know what I would find tomorrow and that was what made getting up tomorrow morning important.

I woke up from my roadside camp to grey, cloudy skies and cool temperatures. I wasn't exactly sure how far it was to Bonners Ferry since I was off my map and was just guessing at the right direction now. I drank tea and glanced at the sky, a bit worried that it might rain on me while I was walking into town. But the clouds just hung on the mountain sides like a down comforter and didn't drop anything on me. I strolled down the road and quickly started meeting with signs of civilization. No Trespassing. Beware of Dog. No Hunting. Private Road.

The land in the area was a traditional checkerboard pattern that the US Forest Service uses to manage the land. Some parcels are private and people live there, either permanently or, increasingly, use the property as a vacation homes or for hunting. As I walked along the road, now paved, it was easy to tell which parcels were private and which were public: There were huge signs screaming at passers by to stay away from the private holdings. Also, there was a 2 mile long unbroken trail of Mike's Hard Lemonade bottles. Seriously, every ten feet or so there was a bottle, like a trail of bread crumbs to lead some drunk home.

But more disturbing than the trash, which can, after all, just be picked up, was the devastation wrought on the land by logging. The checkerboard pattern for loggers is an effective one: Get a square with trees and cut everything down. Then sell the patch of ground back to the government for cash or a tax break. With luck the company that logged the land will follow the law and re-plant it and in thirty years there might be something resembling a forest. Well, at least there might be some trees there.

In order for a forest to really become a forest more time is needed. Time is needed for the trees to reach maturity and to create enough shade to kill off the thick underbrush that springs up in place of the trees. This thick underbrush sits and acts as kindling for forest fires in dry years. Of course, the pine beetle has killed so much of the trees in the area that there is plenty of kindling to spare. I passed a mile of devastated land with only a few trees left to re-seed the area. I stopped at a sign at the end of it and almost doubled over laughing. It was the kind of sign I would put up. A sign to make a point. I doubt the person who put it up thought it was funny. Sure, people need to make a living. But once the parcel of land is cut, that revenue is gone for a long time and there wasn't enough timber to continue to log. No, the logging here didn't sustain lifestyles. It paid for things here and there. Maybe a home. But it wasn't going to last.

The logged over lands gave way to a more pastoral setting, which just meant that the land had been devastated long ago and been allowed to heal into something more useful for human beings than a slag heap. The farms were extensive, though I was not sure if they were functioning businesses or just personal farms. Jeffersonian farms. The growing season in the area must be short and probably only cheap crops could be raised. Some barely. Alfalfa. Hay. Horses. Dairy. These were farms that could benefit people. The image here contrasted heavily with that of the Central Valley of California.

As I entered civilization I began to encounter the bane of mailmen, meter readers, runners, and cyclists. And people on foot. Loose dogs. As I walked past homes occasionally a dog or two or three would come racing out at me, barking and snarling and generally doing their job as a guard of the homestead. Rarely were the dogs behind a fence and they would race out on to the road and challenge me. Dogs, like people, are individuals: They behave basically as dogs, but each one is a little different than the next. Some dogs I would growl at, stomp towards, and force back onto their land. Other dogs I would smile at, clap my hands, and say nice things to. A few I just ignored. I wasn't so much worried about one or two dogs, but rather encountering an entire pack of them. Like humans, dogs behave differently in a pack and their unpredictability, like humans, makes for potentially dangerous encounters. I managed to get through all the dogs and reached US 2 near 11 am, four hours after setting out.

I wasn't terribly happy with being on US 2, one of the major arteries in the area, but at least there was a big shoulder to walk along and the cloudy day continued to provide shade from the sun, which I knew from experience would have made the walk painful. It wasn't far to Moiye Springs, which consisted of a few houses, a gas station, and a bridge over a deep gorge.

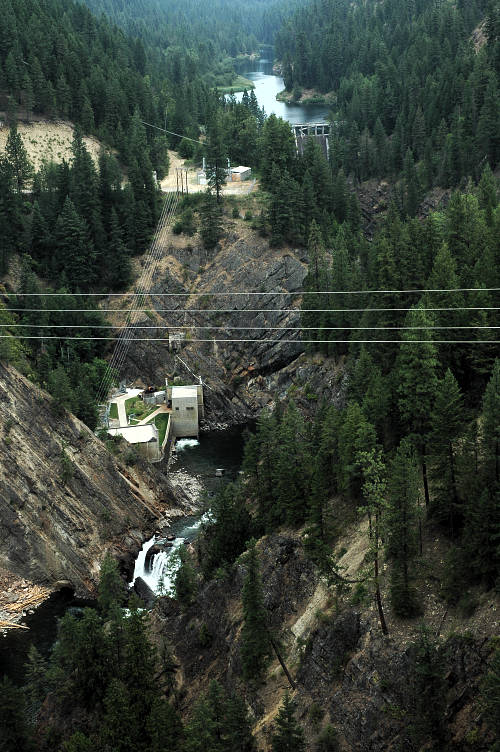

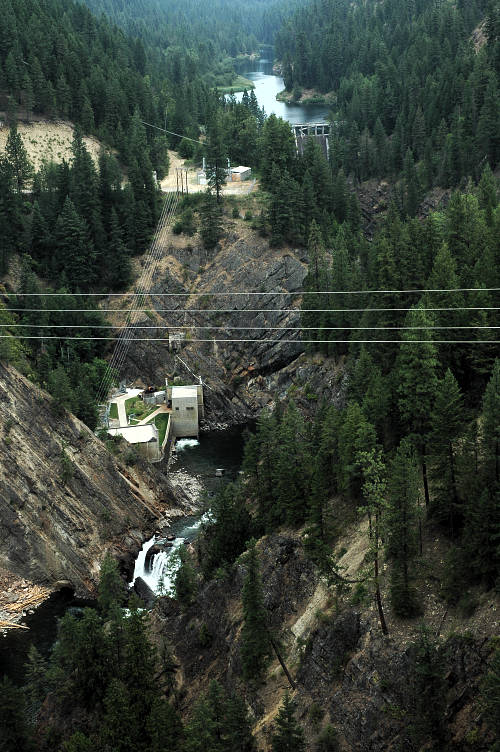

I stopped on the center of the bridge to gawk at the sight below me. The Moiye River was plugged up a few hundred feet below me. The dam held back the waters of the river to be used for agriculture, but the main benefit for the people in the area was the electrical power that its turbines generated. This was much of the story of the modern West: Find any river, put a dam on it in some place where a canyon can hold the water as a reservoir, and sell the idea as flood control or for irrigation. Neither of these two is worth the cost of the dam, either in terms of benefits or in terms of environmental damage. Instead, you bring in the power factor. That is something that can make the numbers work out better. While I didn't especially like damning rivers, I did like having the power come from something other than a coal plant.

My feet were starting to hurt from the long stretch of pavement that I had been on today and the sun was beginning to peek out of the clouds, winking at me ominously. I still had five miles to go to Bonners Ferry, according to the road signs, when a old, beat subcompact pulled over to the side of the road about a hundred yards in front of me. I didn't have my thumb out, but I knew what was coming. Inside of the car was a 30 something man, bearded and tan and wearing a hat and a mellow grin. "Want a ride into town?"

The car was so worn out that I couldn't determine who made it. The body was decomposing in rust and you could look through various body panels and see the inner workings of the car. Like the suspension. Like the motor. As in through the door, past the ripped out insulation, and into the interior. The steering wheel had broken apart some time ago, leaving only a couple of handles on the sides to steer with, just like the old Knight Rider car, KITT. There weren't any gauges left on the dash, and where there used to be a speedometer there was only a black hole leading into the engine compartment. A piece of plywood had been nailgunned on the floor board in front of the passenger seat. No alarms went off in my head. He was taking a chance picking up a stranger who was, by all appearances, homeless. I couldn't let a good deed just die by saying that I wanted to walk to the Pacific. I got in and the car rumbled off. It didn't speed anywhere. The engine slowly, agonizingly, built power and we slowly pulled away from the side of the road.

The man worked as a surveyor for a conservation group in the area. Transient, but with skills. I told him I was walking to the Pacific to see what was in between the mountains and the sea and he understood. He didn't ask a silly question like, "So, is this like a dream of yours?" or "Are you hiking for a cause?". He recognized why I was doing this thing and what it meant to me. He smiled and nodded a lot, as if I was telling him things he knew already, probably because he did. He had explored a bit in the region to the north and west of where I was heading, the southern extension of the Selkirk Mountains. I wasn't sure how I was going to get out of town, but knew that I'd have to cross the Selkirks unless I wanted to walk US 2 all the way home. He gave me the two minute low down on Bonners Ferry as we rolled into town, pointing out a few land marks for me to navigate by. He dropped me off at a Safeway in town and was gone, good deed for the day taken care of.

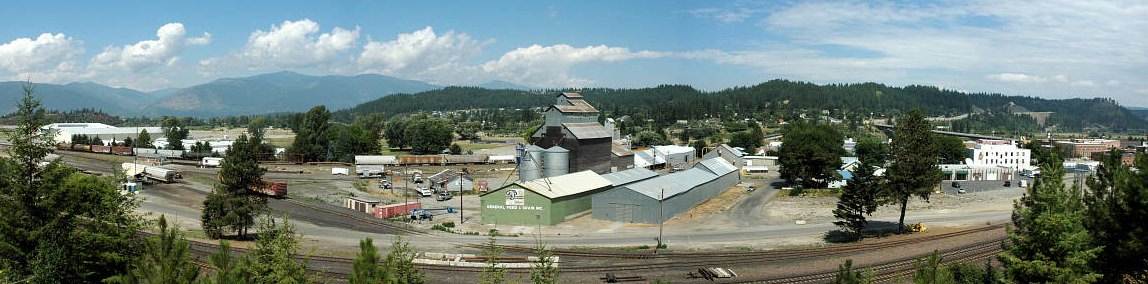

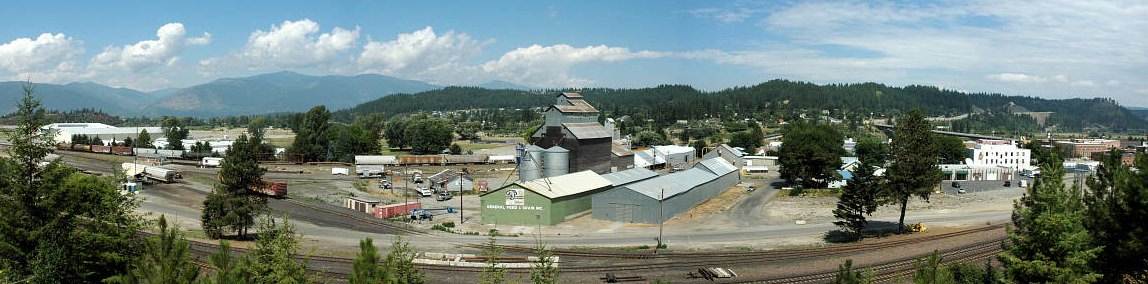

I wandered inside the Safeway to have a look and buy a soda and to look for maps of the area. They had the soda, but no maps, but a friendly woman cashier told me about an outfitter up the hill that would have what I wanted. The walk to the store was pleasant, but uphill. Bonners Ferry is a functioning town with two parts to it. The lower part, where the Safeway was, was where the business end of things took place: Railroads, silos, concrete plant, stores, fairgrounds. The upper part was where people lived. Nice houses with sidewalks, mature trees, well kept lawns and lots of gardens. I found the outfitter and bought a national forest map which had all the trails and forest service roads on it.

My stomach was rumbling and I was in town, which meant it was time for a feed. The problem with hiking and then coming into town is that you really stink. And not just a little bad body odor, but serious, fermenting, stink. It is better not to eat indoors unless you're in a place that caters to hikers, and Bonners Ferry probably saw one or two hikers a year come through town. I stopped at a pizza joint with outside seating, but one look at the menu made me change my mind. I wasn't about to spend $20 on a small pizza. Bonners Ferry is getting the same treatment as places like Sandpoint, ID or Columbia, MT. The wealthy move in and buy up vacation homes. Businesses change their prices and services and eventually the feel of the place moves from authentic to Aspen. Or Vail. Bonners Ferry, I remembered, was one of the quiet, hush-hush, don't tell anyone places. I knew this because I tried to date a girl once who lived out of her truck in Bonners Ferry and worked as a ski guide. But none of this has anything to do with my foul odor and my rumbling stomach. I moved on and found a bar called Mugsy's that had a beer garden with no one else around. Perfect. I sat and quickly had a pint of Moose Drool in hand and a fat cheeseburger in front of me.

I drank a second pint and then a third for good measure. And then I had a huge slice of huckleberry cheesecake. I thought about getting a second round of burger and cheesecake, and another three pints, but thought I should find out where I was going to sleep for the night. I had heard that there was free camping at the fairgrounds, which were behind the Safeway. I bought a few cans of beer and a newspaper and headed over. The fairgrounds were extensive, with a rodeo area, several ball fields, a huge covered pavilion big enough for the high school prom, lots of picnic tables, and a place for RVs to dump their greywater and fill up with fresh stuff. A few people with pickup trucks were filling large water containers, presumably because they didn't have a well on their property. Or, more likely, were squatting out in the forest. I looked around and couldn't find any signs that said camping was allowed, which worried me a bit. I wandered over to the water-fillers to find out what the real deal was.

The three people were clearly on the low end of the economic scale, wearing clothes that had seen work and with weathered skin that had spent a lot of time outside. Two males and one female, they smiled when I walked up and asked where I was coming from. It wasn't anything out of the ordinary to them that I was on foot, with a pack on my back, and no fixed place to call home. I asked them about camping in the fairgrounds, but they were not sure about that. A friend of theirs had gotten run out of the parking lot for sleeping in his truck a few days ago, but for the most part the cops in town were friendly: Just go to the police station and check in. They were living up in the woods in various places, staying for various lengths of time, working hard labor sometimes, but mostly not. They recognized me for someone like them, just without a vehicle at the time. If I had told them that I had a doctorate in mathematics, I doubt they would have believed me. We talked for a while and then I set out for the police station to find out more information about camping. As I walked away, I pondered the reaction I was have gotten from a middle class family having a picnic in the park. I don't think it would have been as friendly, but I could be wrong. The three people were so nice to me because they saw themselves in me. They understood that when you're broke and on foot your options for sleeping are pretty limited. They understood that all I wanted was someplace safe to spend the night where I wouldn't get in anyone's way and wouldn't be run off.

Not being a big fan of the police, I went to the visitors center instead to ask about camping in town. The 90somethings in the air conditioned, pamphlet filled office were nice, but knew absolutely nothing except for what they normally dealt with. Judging from the questions that they got while I was there, most people wanted to know about the casino in town and where they could go for a scenic drive. It took a few minutes to explain what I wanted to do, and then explain that I didn't have a car and couldn't drive 10 miles outside of town. One of them decided to call the city, but had difficulty explaining my situation to them. They just weren't used to dealing with people like me. But a woman came in who was.

Barbara worked for the city and realized that what I wanted to do was simple, easy, and shouldn't be a problem. She took me in hand and walked me down to the city hall where, after discreetly asking me if I had ID to show, she introduced me to a few people. A phone call to the city manager produced the answer: Yes, he can camp at the fair grounds, it is public property. A few more calls were made to the police and the maintenance people just to let them know that I would be there and not to worry. The bathroom would be left open all night.

I walked out of the city hall feeling rather positive about humanity. Bonners Ferry had public land inside the city, a rarity in urban living where benches are no longer put in parks because they cause people to linger. I'm serious about that last point. I know of a city where the parks department intentionally left benches out of its "micro" parks because it didn't want people to loiter. But Bonners Ferry, like Eureka, wasn't like that. They had enough sense to allow people without houses, without fixed addresses, be they hikers, cyclists, vagrants, whomever they might be, they gave these people some space to live. What's the point of a park anyways if you can't loiter? If you can't linger? Of course, if trouble was caused the offenders would be given the boot, but until then, why not give them space? Back in Seattle the city was continually battling with so-called "homeless camps", fighting to keep them out and driving their inhabitants to "shelters" instead. Shelters where they could be kept in a pen and watched over so they didn't do anything subversive, like smoking a joint or drinking a can of Steel Reserve. Idaho and Montana, bastions of backward conservative thinking, were more enlightened, more progressive than Seattle.

I wandered back to the park and sat down to drink some beer and read the paper. I had little else to do during the day, especially as I was contemplating taking a zero day here in Bonners Ferry. I had really liked Eureka once I got to know it and was already digging Bonners Ferry. I could stay for free and had a bathroom with sinks (aka, laundry) at my disposal. I drank a tall can of strong beer and then started another. A man in a pick up truck drove up and introduced himself as a supervisor at the city. He had been told I'd be here and wanted to come by and make sure I knew about the sprinklers and where I could camp and stay out of their wash. We talked for a while about my trip and the area. He left with a smile.

I set up my tarp near the fence of the rodeo area, exactly where the man from the city told me was missed by the sprinklers. I washed clothes in the bathroom and drank my second can of beer in the sunshine, generally feeling good about how my summer was shaping up. Even though I wouldn't have a continual line of travel on foot between the Rockies and the Pacific, I had had a good day, meeting interesting people and getting a feel for how a certain segment of the population lived. A segment left behind by the mainstream, either by choice or by tragedy. Two more people came and went, also from the city, wanting to know only if I had everything I needed and to warn me about the sprinklers. I think they were just interested in who I was and what I was doing in town. We exchanged the now usual words. And then it struck me that not once during the summer had anyone asked me if I had a job or a regular living. A home. A family. They all seemed to accept me for who I appeared to be: Someone on foot, out to see the countryside. Only rarely had I mentioned the PNT, and then only when I was dealing with someone who wouldn't understand the real reasons for my being out this summer. Acceptance is a forerunner of community. The surprise that I had a stronger feeling of community out here, on the road, was shocking. At home, I don't even know the names of my neighbors, but in Bonners Ferry I already knew a score of people by their first name. In Eureka there were yet more. In East Glacier still more.

I spent the early evening doing what hikers do in towns: I ate dinner and hauled a stash of ice cream, beer, and a Backpacker magazine back to my tarp. I ate the pint of Ben and Jerry's and had just started in on a 24 oz can of beer when the urge to use the bathroom came. When I got back from the concrete blockhouse, I found a man in a Carhartt jacket, ancient blue jeans, work boots, a plaid shirt, and wild hair sitting on a picnic bench twenty feet from the tarp, a can of Steel Reserve in his hand. I picked up my can of Coors and wandered over. This is how I met Jason.

Jason was scruffy. His hair was unkempt and oily. He hadn't shaved in a few days. His clothes were dull in the way that clothes get when they are worn for days in a row and not washed. He was as beat as the car that I had gotten a ride from earlier today. I had seen him walking around the park in the afternoon and early evening and now here he was, near my tarp drinking beer with me. Jason was homeless and assumed I was also. He had gotten out of jail last week after a stretch for DUI and had lost his car. He worked at the fairgrounds as a groundskeeper but hadn't gotten paid yet and so was living here until he could afford to live indoors. Jason was a few years older than me and had been living on the road since he was a boy. When he was 11 his mother abandoned the family and went back to Boston. Two years later his father and his aunt were murdered in front of him and he was taken in by his stepmother and her new boyfriend. They lived in southern Oregon for a few years before they kicked him out. And so he took to the road, traveling through the Pacific Northwest and to Alaska, where he was married to a Native American woman for a while. He worked on a crab boat and had money and a car. But his wife didn't like him being away for so long at a time and after his second cruise he came back to an empty house.

He left Alaska and hitched back toward Idaho. He was stopped at the border and denied entry in the US because he had no identification and was piss drunk at the time. He went into the woods, slept off his drunk, and crossed the border illegally on foot. He searched out and found his brother. Although he thought everything was going well, the night he found him Jason got drunk on a case of beer and went to sleep in the brother's car. The brother called the police and had him arrested on trespassing charges. Now he lived, as he said it, permanently on the road. He would never leave it even though it was cruel to him most of the time. He told me of the time that he took to traveling with an Eskimo (Jason is half Native American on his mother's side). They passed through Seattle on a bus and got a cheap motel for the night. They quarreled and the Eskimo ended up putting a hatchet into Jason's head. He even showed me the scars. Other injuries, other problems. He got drunk one night and was wandering home when a car hit him and put him into a drainage ditch for the night. He had jobs at times, but never for long, and frequently got fired for being drunk or high on the job or for fighting with his boss. When he needed food he would go to a restaurant, to the back of it, and ask at the service entrance if they needed help for a couple of hours. He had "...two hands and a back..." and could put in enough work for a meal. Normally the restaurant would just give him leftovers, but sometimes he found himself with a job for a few days. He hunted when he could, having been taught by his father at a young age. Porcupine was good eating, he said.

As he roamed about, the problem of where "...to lay my neck tonight..." was one that he faced all the time. In the winter, he told me, the best thing to do was to go to the police station in town and tell them your story."I all wore out and can't move on. Where can I sleep?" Sometimes the cops would tell him to get lost, other times they'd take him to a motel and arrange for a room for him for the night. In the summer, when it was nice out, there was no reason to sleep indoors. The cops in Bonners Ferry were good people, echoing the comments of the three people I had talked to earlier. But stay away from the young one with red hair, he warned ominously.

I didn't know this all at once. It came out in a jumble as we talked, sharing stories of the road over cans of beer. Jason had to go to a court mandated Alcoholics Anonymous meeting tomorrow morning, which I thought hysterical, but had the good sense not to laugh at. For Jason, it was just the ordinary state of affairs, much like me saying that I had to put gas in my car. When I mentioned that I needed to buy some food tomorrow to get me to the next town, he produced a package of hot dogs and insisted that I take them. He had gotten them from the food bank in town this morning and suggested that I visit it instead of going to the store. It was past midnight and Jason was fully loaded, barely able to stand and slurring heavily. I wandered off to go to sleep and he disappeared for a while. He came back with a sleeping bag in his arms for me: He was worried that it would be cold over night and had an extra sleeping bag for me to use. I showed him mine and he went off to sleep out of sight, for he didn't want to run into the red haired cop.

I laid in my sleeping bag for a while thinking about Jason and what his life meant, to me, to society, to the Land. Like the people getting water, like the surveyor, the way Jason had treated me, had dealt with me, was a reflection of themselves, of their of life experiences. Jason probably wouldn't be alive much longer. He would die of alcohol poisoning, or be run over by a car, or be shot by an irate husband, or drown in a river, or have his throat cut by some one meaner than he was. As much as I was enjoying the summer, I didn't want to live like he did, I didn't envy him, I didn't want to be like him, and when I returned home and put on dress slacks and a button down shirt once again I'd probably hide in fear from him. But his life and his story had meaning for me. I was richer now than when I sat down to eat the ice cream. I was richer than when I got on the train to go to East Glacier. I was richer because I was out here allowing myself to accumulate the wealth of experience, of doing new things and meeting new people, of existing in a way that was fundamentally different from how I normally lived. What I would do with my new found wealth was another matter. I didn't know what everything meant or how to interpret the experiences I had had today. Or yesterday. Or the week before. But I had time to think it through just like I had the time to gather new experiences. I had enough time on my hands that I could think it over at length and determine what meaning Jason's life had for me beyond simple quaintness. What meaning was there beyond an amusing story that I could tell my friends over beers at The Harmon when I went back home and cleaned myself up and became a respectable member of society. I didn't have to work it all out there, under my tarp in the black of night. I had time.