Out There

Bonners Ferry, ID to Northport, WA

July 24, 2008

I wasn't going anywhere today and took the luxury of sleeping in until 8 am to enjoy the morning of a zero day completely. I felt a little sorry for Jason, for I had seen him and the rest of the grounds crew starting work at 6 am while I still dozed in comfort. When I finally pulled myself from my sleeping bag I didn't do anything more strenuous than walk to the diner I had dinner in the night before and sat down for two hours of omelet (bacon, sausage, and cheese), coffee (one gallon), and newspaper. When you have nothing to do all day, you can spend a lot of time doing nothing in particular.

The day was starting to heat up as I walked across town, all three blocks, to the library, which was a modern, spacious place with plenty of computers to use. I spent some time on the internet, sending out updates to friends and family, checked the weather for the next few days, and generally did nothing of actual value. But on my way out of the library, all that changed. Sitting on a bench in the front was a man next to a touring bike. But unlike others that I had seen this summer, he was carrying very little on the bike: Two panniers and nothing else. He was about my age with medium length curly black hair and a scraggly beard. His cycling outfit was dirty and he had clearly just ridden in from some camping spot in the woods. I walked up and introduced myself.

John and his girlfriend lived in Port Angeles, which I was familiar with from hiking and climbing in the Olympics, where they worked as wildlife biologists. He was unemployed this summer and was cycling from Neah Bay to his childhood home in Grand Rapids, MI. Neah Bay is the most northwesterly point in the contiguous US, though technically it isn't in the US: It is located in the Makah Nation. He wanted to spend a summer traveling without the use of fossil fuels and to re-connect with his roots. I told him about my journey and were surprised at how similar they were: Ultralight approaches, both heading home, both human powered. We swapped tips for the land and area that each of us would be passing through soon, but quickly left the unimportant logistical stuff behind. John understood. He understood why someone would voluntarily live out of doors with as little as possible for a long time. He understood the attraction of the freedom that such a trip allows and the understanding of what is important that it engenders. We were on the same journey, but he was heading toward the rising sun and I was heading toward the setting. We talked for a half hour outside of the library and then parted ways.

Note: When I returned from the trip John sent me an email to let me know that he made it to Grand Rapids after 26 days and 2,711 miles of cycling. In his email, which I hope he will forgive me for quoting in public, was the following few lines which struck me directly in my heart.

"I am having a hard time formulating a response to friends and family's questions of "How was your trip?" as if this is something you simply summarize into a primitive sentence structure, toss in a couple adjectives, and infuse excitement into. The difficulty comes from knowing, for most, my response is the closest they will come to living portions of their life "out there", experiencing freedom from the monotony of routine, or at the very least, providing a short detour to the death march they feel like they are in."

He also attached a few pictures and the one below is from him a few days later as he crossed through Glacier National Park.

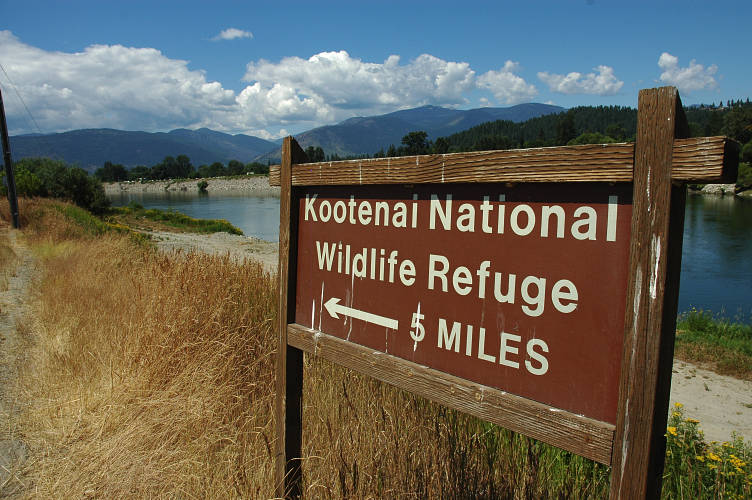

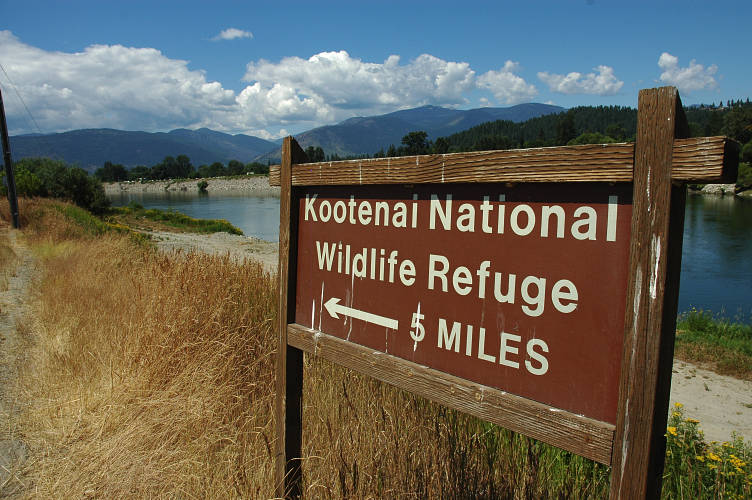

I left John feeling inspired to hike on today. As much as I had enjoyed Bonners Ferry, as much as I had liked listening to and talking with Jason, as much as I wanted another far Cajun burger and five pints of Moose Drool at Mugsy's, as much as I wanted all these things I now wanted to get back out onto the road. I went to Safeway and bought supplies for another few days, just enough, I hoped, to get me to Metaline Falls, WA. I had mapped out a route that took me through the Kootenai Wildlife National Wildlife Refuge, then up and over the Selkirks and down to Priest Lake. From there I could re-join the PNT, or take another route that would avoid what previous PNT hikers called the worst hiking on the entire PNT. My enthusiasm for hiking was tempered by the heat of the day, however, and so after packing up, I sat in the shade with a half gallon of lemonade and the copy of Backpacker that I had bought yesterday. The cover story was about a man who had spent a few decades walking across America multiple times. And never riding in cars. And didn't talk. And somehow had gotten a PhD along the way. It was blazing hot when I set out on the road once again.

The road out of town took me through abandoned industrial section of town where the concrete plant once operated. The abandoned (more properly, not used) parcel of land was extensive, enormous. And it sat growing weeds, waiting for someone to come along and use it for something good. Instead, it would most likely be de-polluted and converted into luxury vacation homes and condos for the wealthy people that had "discovered" northern Idaho. What would be better? Well, the city could seize the land, kick the "owners" off of it for not using it, and turn it into a large park for the benefit of the citizens. It fronted the river and would have made for an excellent community resource. It would increase the quality of life for the residents of the city and the people of the surrounding areas. Or, they could build affordable homes for people to live in instead of living in trailers waiting for a tornado to come through. But our laws don't work like this and the city would never have enough resources to buy the land back from the corporation that owned it and let it sit idle.

Once beyond the former concrete plant the countryside turned rural very quickly and the homes and businesses of the city were replaced with farms that supported a family, not an agribusiness. I found myself strangely enjoying the road walk, as I had many of the others this summer. People would stop occasionally and ask me if I was alright, or if I needed a lift. We'd exchange a few words and they would drive off with a smile. The heat was powerful as I was walking through the hottest part of the day and there was little shade along the road. But this didn't bother me much either: It was just how things were and to think on it didn't occur to me.

The wildlife refuge, like many others that I had been to in the past, was devoted to the birds that migrated through the area. The regions wetlands had been drained long ago and this was all that was left for the birds to rest in during their migrations. For me, however, it meant the end of pavement, for I soon turned off on Myrtle Creek Road and began the climb into the Selkirks.

The improved gravel road gained elevation steadily as it lifted me off of the valley floor, giving an excellent perspective on the valley I had come through to get to Bonners Ferry and the wildlife refuge itself. The Kootenai cut through the broad valley and provided the lifeblood of Bonners Ferry, while the mountains rimming it formed an alpine playground in the winter for backcountry skiers, snowshoers, and snowmobilers. People could hunt and fish in them, collect mushrooms on the forested slopes, drink beer in sheltered glades, picnic, whatever it was they wanted to do: The land was there for them to use. I took a long rest in the shade at an overlook and thought about the area, the land, the people. People seemed happy here, even Jason, who lived in a park, had only the clothes he was wearing, and had to go to AA meetings after a night of hard drinking.

The climb continued through a burned area that had no shade. I pushed on through the heat, sweating hard, and pondering why I didn't collect water before I started up. I turned up the volume on the radio, searching for the faint signals of stations that might have enough good music to keep me moving. A rock station from Spokane came through clear and static free, giving me sounds to hike by, to move by. Songs that I would have kept spinning the dial past brought joy to my sun addled body. There was something about being out here, I thought, that amplified every experience. A burger wasn't just a lump of meat. A tree shaking in the wind wasn't just a bunch of bark and leaves. A crow flying about wasn't just another scavenger. Life was turned up to 11. You couldn't ignore the things that you ignored, or rather were forced to ignore, back at home, in the comfort of a routine and surroundings that promised safety and security and complete and utter suffocation of aliveness. I found a cascading stream tumbling down the mountain side and called the place, in the shade of a few trees, my dining room for the evening. I scrambled down a few boulders to get to the icy water and when I returned I startled a coyote sniffing at my pack.

I ate a delicious dinner of Idahoan mashed potatoes (Loaded Baked) and drank copious amounts of water to recover from the sun and the heat of the day. It was pleasantly cool in the shade and had it been earlier in the day, I would have napped the afternoon away in a fit of luxury. I wanted to get a bit higher up in the mountains, however, before calling the day done and so set off after an hour of lounging. I hiked up until I got a look at the Selkirk Crest that I would have to get through tomorrow. It looked pretty big from down here: Big, blocky granitic expanses with a couple of different places where a pass might be. I passed a hunters camp, complete with a cabin tent, but continued on for another hundred yards to where I saw an ATV track leading into the woods. I followed it, reached a river, and another hunter camp, though this one without a tent in it. I quickly set up my tarp and put on my down jacket and hat, for it was getting cold quickly even though the sun was still out. It just wasn't shining on me.

I got inside of my sleeping bag and ate raspberry newtons as I wrote about the day in my journal. I wondered what Jason was doing (probably getting lit in the park) and where John was (probably near Glacier). Bonners Ferry had been an important stop for me and for my summer. Although I enjoyed the backcountry, I had found myself increasing drawn to other, less wild attractions. Meeting and engaging people that I normally wouldn't have was proving to be a highlight for me. While the time spent on Thoma or Henry were well spent, I suspected that I would remember and think over people like Jason or John more in the future. After all, I've been on top of many mountains. I have them in my backyard and can go to them any time. But the people I was meeting were something different. I didn't have access to them anytime I wanted. My trip was quickly devolving from a thruhike into something else, something other than what I had done before. I didn't have the language to describe it, but I had the time to work on this problem.

Cold. My nose was cold. I pulled my hat a little lower and snuggled deeper into my sleeping bag. Cold enough to keep me awake, cold enough for my body to tell me that I needed to do something in order to maintain it. I reached out in the dark and opened up the stuff sack that was functioning as a pillow and took out my down jacket. I slipped that one and my thing gloves and curled up as much as I could in the sleeping bag. It was still pitch black out.

I went through my morning ritual in the cold air of the morning, drinking tea and eating preservative laden "Oatmeal" squares and looking at my route for the day. I decided to skip the PNT route past Priest Lake and instead follow a faint line on the map that would take me up and over Pass Creek Pass and down, directly, into Metaline Falls. That wouldn't be for a few more days, though. I had to deal with the Selkirk Crest this morning, which meant finding Two Mouth Pass, or at least that was what I was calling it, for it had no name on my map. Near by, on the far side, were two tarns called the Two Mouth Lakes and there was a trail, on the map at least, to them and down to Priest Lake.

I set off at 7:30, following the road for two more miles to the trailhead. The road was sunny and warm and I delighted in the warmth after so much cold over night. The Selkirks were big slabs of granite, the same rock that makes up the mountains of the Yosemite Valley and the Squamish Chief. Further north, in Canada, the Selkiks are one of the most brutal mountain ranges in the world and held one of the most impressive alpine climbing areas in the world: The Bugaboo Mountains. The Bugaboos are sharp, steep granite mountains coming directly out of glaciers. With high quality, solid rock and routes for all abilities, from short to long, the range is on the hit list of almost every climber I know.

The trailhead for Two Mouth Pass wasn't much to look at, but the trail was obviously well cared for by the local hikers. There were boardwalks and log bridges when the track went over water or through swamps The branches were cut back, so that the winter's growth wouldn't hamper a family out for a stroll. Water bars were dug so that rain wouldn't cascade down the trail. Trail maintenance took time and sweat. People did it because they were connected with the land and took pride in the result. Anyone could let a trail wither away to nothing. I had seen that plenty so far this summer. But it took a special group of people to maintain a trail to a high standard, and this was one of the best ones I had been on in a while.

I sweated my way up fifteen hundred or so vertical feet, enjoying the views and the mountain air, still refreshingly cool, along the way to the pass. The pass itself was, like the mountains around it, broad and rocky, but not crumbly. It was a large slab of rock, with boulders strewn about and trees and other shrubbery filling it. I climbed up a boulder for a view around me and sat on top, perched like a crow on a roof, surveying my domain. I should have given a howl or a whoop, but I put my backside on the rock and just looked up at the sky instead. The breeze swept across my sweaty skin and cooled me, refreshed me. Sitting on the rock was all I wanted to do right then. Sit and feel the breeze and look at what was around me. This was not human behavior. And with that thought, it was gone. Time to go.

I hopped off the boulder and began down the other side of the pass, following the still excellent trail as it weaved its way through stands of trees and other obstacles. Huge slabs of granite spread out and I stopped occasionally to look at various lines on some of the mountains, imagining what a rope, harness, shoes, and a partner would let me do out here. But that was another activity, and a radically different one at that. Climbing is inherently confrontational with nature: You conquer a mountain, or it lets you survive it. You sneak up it and run away before it knows you're there. Hiking is different. It is mutual coexistence.

I descended to the lakes while pondering this favorite question of mine and promptly lost the true way. The lakes were obviously popular for there were use-trails going everywhere. There were no signs and no way of knowing which way was the correct way to go. This is not as bad as it sounds, for when you have no way to make a good decision, just make any decision and hope for the best. I set out down one trail that looked like it went in the right direction, switched to another, then another, rock hopped an inlet stream, bushwhacked through some woods, and found a cairn.

Hooray for me! But, search as I might, I couldn't find a second cairn. In either direction. I gave a metaphysical shrug of the shoulders and headed into the woods, following granite ramps when I could. I fought through brush to get to a long stretch of granite. I would follow it down as far as I could before getting cliffed out or it ended, then head downslope through thick brush trying to find another ramp. The bushwhacking required extensive time to get through and there were times that I had to remind myself to be patient, for a broken ankle or wrenched knee out here, far from a trail, would probably be the end of me. At the second or third ramp, I came to an extensive view point where I could see Priest Lake in the distance and the valley leading to it. Somewhere in there, I thought, there is a trail. Just need to find it.

I fought through the woods to another ramp which split to the the left and to the right. My arms and face were scratched from the trees and sap clung to my clothes. Pine needles filled my shoes. I explored to the right and it seemed that I'd be able to downclimb through the rock to reach a larger, more open area lower. The left was simpler, but lost less elevation. I went left. I had the time to go safely. The ramp slanted downward, steeply at time, forcing me to pay attention to my feet and balance, but I made progress downward and leftward in a steady way. And then, at the end of it, I spied a cairn. Pleased with myself, I walked off the ramp and into the woods, where I found another cairn. And then another. I found myself at a fourth cairn by a pleasant creek and sat down by its banks for some water and food. I knew that I had found the track only sheer dumb luck, but pretended I didn't know this and took some pride in my skills.

I had a good rest and then started down once again. I wasn't on maintained, dug trail and lost my way occasionally, but never for long. There were game trails crisscrossing the track and I detoured onto a few, only to have to bushwhack for short stretches when they gave out. After one final bushwhack I reached solid trail and something that even a blind man could follow. As I descended the air became hotter and hotter. Still in the shade, I was, for the most part, quite comfortable. But occasionally the trail would cross through areas exposed to the sun and then I would roast. The track neared the creek again, passing a large exposed granite slab the size of a football field where I heard some voices. A man and a woman were camped on the granite by the river and were sunning themselves on the rock. Naked. I kept going to preserve their sense of wilderness.

I passed one junction after another, always taking the route that seemed largest, and finally hit an unpaved road where a pickup truck was parked, belonging, no doubt, to the sun bathers higher up. It was hot here, this low in the mountains and with complete sun coverage. I walked down the road, though my gate became more of a stumble the lower I went and the more the sun had a chance to work on me. The unpaved road I was on ran right into a well paved road that I had heard from a ways off. This was not a good sign.

The paved road had traffic. A few cars every minute would pass me by, the people chained to their vehicles looking at me with a mixture of curiosity and fear. I didn't understand where the looks were coming from until a man on a six wheeled ATV drove up a path leading down to the lake and the past me, keeping a watchful eye on me the whole time. Looking down the path I saw it. Luxury vacation homes. As I went a bit further the No Trespassing and Private Property signs became more and more common. The people in the cars were starring at me in strange ways because they thought I didn't belong there. I clearly didn't have the resources to live in the area, unless, of course, I was a maintenance person. But then I would have a vehicle of some sort, wouldn't I? If I didn't live here and didn't work here, what business of mine was it to come here? I didn't belong and should get out. The two patrol cars from the sheriff's department that drove by me, over the hour and a half I was on the road, didn't stare me down, which I took as a sign of the superior intelligence of the local cops over the vacation home owners.

I passed several people on bicycles and waved and said hello to them. I got nervous stares instead of the usual friendly response. People were, I realized, afraid of me. I hadn't done anything, I wasn't carrying any weapons, I didn't leer at them or curse at them or otherwise threaten them. But the people were threatened nonetheless. I reached the state campground I was aiming for, found it full, and pushed on. As I walked through the campground to the lake I felt the same eyes upon me. Wondering. Suspicious. Uncertain. In their eyes I didn't belong and was therefore suspect. I came out to a beach where there were some picnic tables in the shade that I could sit at while I made dinner by the lake.

The lakeshore was crowded with people, families mostly, each of whom wore a terribly red sunburn apparently as a badge of honor. I drew a few stares, especially when I started cooking, but the residents of the beach got used to me and eventually just ignored me, pretending that there wasn't a homeless person eating dinner in the shade of a tree on a picnic table. I felt slightly ill and got ready to move as soon as I could. As I was packing up a man in a golf cart rolled up, but rather than being here to run me off he was there, instead, to remind several groups of people that blaring music from their SUVs in the parking lot was a noise ordinance violation. I chatted with the old man, who was quite friendly, about where was a good place for me to camp overnight. I set out down the road, but quickly dodged over onto an ATV track that took me deep into the woods and away from the vacation set.

The dark path was rutted heavily from ATV and ORV traffic, but after a mile or so, and a river ford, a large sign was prominently placed next to the trail saying that motorized vehicles were prohibited from going any further. The quality of the trail improved greatly for the last mile I had to walk to get to the lakeshore and a boat or foot only campground. I thought, during my walk, why I had seemed like such a danger to the vacationers along Priest Lake. It first occurred to me that I was seen as a threat simply because I was unknown, but that didn't hold much water. I had been an unknown to many people this summer, but had been treated with warmth and kindness. Rather, I suspected that being vacationers, and hence not permanent residents of the area to watch over their costly cottages and quaint log cabins, they might be worried that I, who apparently possessed nothing, but want to appropriate some of their excess goods for my own use. Or just take a crap in their homes while they were out.

Locals, people who actually lived in the area, didn't seem at all bothered by me. No one in East Glacier or Polebridge or Eureka or Bonners Ferry had seemed threatened by me. But here, with excessive wealth on display, people were afraid. Fear was a bad thing. Therefore, excessive wealth was a bad thing. I grinned at my naive reasoning and greeted the other members of the campsite, a family of four who had canoed in earlier in the day and were just setting out for a post dinner hike along the shore. They smiled a lot. I appreciated the friendliness and told them a good story about my summer in return.

The family left and I took the opportunity to go for a swim. The clothes came off quickly and I splashed around the lake, enjoying the still warm water despite the setting sun. I swam for a bit and floated on my back. I dove underwater and scrubbed my beard and hair to get the salt out. It was idyllic, I thought. This summer, this time, this right now moment, was idyllic. I could never duplicate this feeling or this time. I had to enjoy it right now, for it would never come again, no matter what I did or how much I wanted it. I splashed some more.

I was feeling so good after the swim that I didn't bother to go and bark at the group of seven ATV and motorcycle riders that pulled up in the campsite just as night was coming. They would have passed right by the no motorized vehicle sign, ignoring it with a sense of entitlement. Or maybe they just didn't care. Or were illiterate. Whatever it was, I didn't care much either and instead sat under my tarp, shirtless, writing about the day in my journal. They would leave eventually and take their stinking machines with them, and all would be quiet and peaceful once more. I could wait.

I was moving early in the morning to get a jump on the heat of the day which, given yesterday's sweatfest, would be extreme once again. I walked back up the trail to the campsite and rejoined the PNT for a lovely stroll through the woods. The trail would occasionally run down to the lakeshore and provided very nice views of the lake and the mountains surrounding it. I passed a few other boat-in campgrounds as I moved down the lake, though these were occupied by people with power boats who had simply pushed a throttle to get here, as opposed to the family I had spent the night with who had expended their own energy. The forest was mature and deep and it was with some regret that I left it for a dirt road. It went no further.

I had already made my decision to avoid the unmaintained trails that the PNT followed, after copious road walking, to reach another road that I'd have to hitchhike on to get to Metaline Falls. Why not just take a direct route? I made a left instead of a right and wandered down the gravel road, which was deserted at the early hour. The only people who get up early in the outdoors are hikers, climbers, hunters, fishermen. People who engage the natural world. ATV riders, vacationers, gawkers, these people sleep in. But they get up eventually and start up their vehicles.

I shouldn't complain, since I was, after all, on a road on a weekend in a very popular area. But, at least the diesel spewing pickup trucks could slow down from 40 miles per hour to something a bit more friendly. The ATV riders, and many passed me, rarely slowed down. A few locals stopped to ask me if I needed anything or to see where I was headed. But I for the most part the road was not much fun and it was getting hot out to boot. I was hot and sweaty and dust covered me when I reached another border. I was home.

I rested and ate lunch in a shady roadside campsite, complete with cold, perfect water from a spring that I had found nearby. Trucks raced down the road as I ate and I began to doubt the wisdom of my choice of routes. But only a half hour further on I reached Granite Pass and turned off of the main road and onto a smaller, rocky track that would lead me to Pass Creek Pass. The sun was out in force, but I was several thousand feet above the Priest Lake valley and gaining elevation, which moderated its effect on me.

I sat by the side of the road and took a break in the shade. Almost instantly a jeep came whining down from the pass in low gear, moving almost as slowly as I was, for the road was heavily pitted and rocky. Inside was a woman and her two dogs and they seemed rather surprised to see me. She pulled up alongside of me and offered me some water, but I suspect she really just wanted to find out what I was doing up here, all alone and without a vehicle. I told her a little bit about the trip, but was too tired from the climbing to muster any good stories. She pushed on and I returned to my rest in the shade. Just beyond my resting place I came to an area that had burned a decade ago and which had open views of the pass and the surrounding mountains.

As I neared the pass I gained an excellent view of the land that I had come from not long ago. In the far distance were the Selkirks, but immediately below me was the valley and the road that I had climbed coming out of Granite Pass. Priest Lake was hidden behind some low hills. Surveying the land, I felt glad that I had come this way. Walking the road had been physically tiring, but there were rewards at the top, it had been almost empty of cars, and I didn't have to worry about blowdowns or bushwhacking. The skies even clouded up for me and a wind picked up, cooling me pleasantly for the last push to the pass. A big red pickup truck was parked there by a trail head for a route heading up one of the guardian mountains at the pass.

I moved to the other side of the pass to get a view of the mountains of my future. I had left one watershed completely and was moving into another. I had left the Priest Valley for the Metaline. Down below was another culture, another community, another place which had developed according to the land and the isolation that it brought. I was in Washington again, but in a part that I had never been to before. Even from my roost at 6000 feet, I couldn't see the Cascades, my home range. I rested until the breeze had cooled me to the point of discomfort, then set out with a smile on my face, descending the road as slowly as I could. I thought about camping at the pass, but there was no water there and if it rained tonight I wanted some shelter from the wind. Wildflowers were out in abundance, providing a healthy splash of color amidst the greens of the shrubs and trees.

I wandered for another forty minutes, enjoying the views and the flowers and the smell of the air. Although it was only a quarter to six, I found an excellent campsite, complete with a little trail that I could walk to get a view of the valley and cold spring water nearby. There were no bugs and there were no cars. Twenty four miles was enough, I decided. I tossed my pack next to a downed tree where I could sit with some back support and then went about my normal routine of setting up camp. I located a flat bit of ground and set up my tarp. I fetched water from the stream and started boiling water for dinner. While the water heated I unpacked the rest of my gear and had a seat next to the stove with my maps, journal, and book. Ten minutes is all that is needed.

While I stuffed Broccoli Cheddar Rice and Sauce (Litpon's flavor) the red truck from the rolled slowly past me. Inside the cab was a man in his 50s with a long, white beard. He asked me if I wanted a lift into town, to which I smiled and waved my hands toward my bedroom for the night. He grinned and understood. I was alone once again. I spent the evening reading Hesse and writing in my journal. I was trying to understand what to call this summer's journey, for it was definitely not a traditional thruhike. I was taking my own route, eschewing the guidebook when it didn't make sense to me and following it when didn't have any better ideas. I was freely taking to roads, something I hadn't done before. And I was liking them. The walk over Pass Creek Pass had been very pleasant, with outstanding views at the top, plenty of water, and no brush. I wasn't on a thruhike, for I wasn't following any particular route. I wasn't on a pilgrimage for there was no religious reason or goal for my wandering. I could call it a Vagrancy, or a Wandering, or a Hobo, but these words didn't seem to have the right meaning. They didn't express what it was that I was trying to do, which was to see my neighborhood on foot and spend a summer living out-of-doors without a fixed address, schedule, or purpose. I took my socks off and put my feet up on my pack to dry in the cool night air instead of thinking any longer on something of such dubious merit as the name of the Thing.

It was completely dark in the outside world, which is what bothered me. I lifted the flaps of my hat over my ears so that I could hear better. I scanned the area with my eyes, trying to pick out movement in the darkness rather than form. Something had woken me up and I didn't know what it was. It wasn't the rising sun, for the air was black, not purple. It wasn't a deer or a bear, for I would have heard it by now. It was unlikely to be a human, but there was something here that had bothered my unconscious senses enough to wake me up. Something was here. I could feel it. I stayed very still and breathed as shallowly as I could. I listened and smelled. I smelled only the woods, which ruled out a human from town, their clothes saturated in laundry detergent, their bodies pungent with deodorant. With fakeness. Something had been here. Or was still here. I don't know how long I stayed awake, but at some point I drifted off to sleep, my senses telling my mind that all was well, or at least that whatever it was, it meant no harm.

I sat on my dinner log drinking tea in the morning sun and thought about ritual and habit, pattern and addiction, a rut and a routine. I know people who go for long distance hikes every summer because they cannot imagine doing anything else. Were they stuck in a rut, or simply doing what they loved? This is what I thought about at 6:30 in the morning, feeling refreshed from my night's sleep and trying not to think about what it was that had woken me up in the middle of the night. My worst pair of socks were gone. I had set them next to my shoes, where I had taken them off, under my tarp. Next to my head. And they were gone. I had searched the surrounding area, couldn't find them. I packed up and set off down the gravel track. Wildflowers were abundant, giving a nice local view to contrast the far vistas of the Pend Oreille valley.

About thirty minutes after setting out, a large, lumbering white SUV with green and brown highlights crawled slowly up the hill toward me. Remembering my last encounter with the border patrol, I wasn't especially happy to see the agent approaching me. But this time the agent was different. He didn't have a Joe Friday routine to put me through. We chatted, friendly like, about the area and my trip and about Metaline Falls. During the course of our twenty minute conversation he found out all the information he needed to know and correctly assessed me as no threat at all to run across the border. Although he said he was out on a routine patrol, the fact that, after we talked, he almost immediately turned around and went back down seemed to indicate that he had been alerted to my presence by the man in the red truck. Although I wasn't sure if it was a good use of tax payer dollars, at least the agent had been kind, polite, and professional in his approach to interviewing me. Given my appearance, that said a lot about the character of the border agent.

After eight miles I reached the end of my pleasant gravel track and intersected Forest Service Road #22, which followed, as so many roads in the west do, a river. Ample camping, with plenty of campers, were strewn along the roadside. It was shady and the walking, if not view-filled, was nice. As the day began to warm, however, the number of cars on the road began to pick up and by the time I reached FS Road #9345 I was hot and traffic addled. My shade was gone, my feet hurt, and I was chafing rather badly in places not mentionable to the general public.

My radio provided great relief along the road, which was getting hotter by the moment. I switched between a Spokane rock station and NPR according to what needed more help at the time: My body or my mind. The sweat poured off of me as I pounded the pavement and it was with a great sense of relief that I reached SR 31 and my route into Metaline Falls.

The road into town wasn't exactly safe. In fact, I'd probably classify walking on it as rather dangerous. It dropped steeply to the Pend Oreille river via a sequence of tight turns with little shoulder and no place to move if a car erred just a little. A few drivers honked at me as I walked down the road, usually with a smile and a wave. A car load of youths flashed their lights and many hands came out of the windows to wave. I began to move through the outskirts of town, passing an old power station on Mill Creek along the way. It seemed to have been abandoned quite some time ago, yet hadn't been torn down. There was a big dam just upstream on the Pend Oreille, so why was this still here? Mill Creek had been freed, but the power house stayed. Why?

It was 1:15 when I walked into downtown Metaline Falls. Perfect, I thought. This might even rival Cascade Locks as the best trailtown I'd come across. I walked past the lush green city park, which also held the visitors center (in some old railroad cars) and made a right turn to Cathy's, the sole diner in town. Two men in their late 50s were sitting at a table outside smoking and arguing about high school basketball. I dropped my pack and sat at the other table outside, stomach rumbling now that I was in town and within reach of fat food. Although it took some time for the pregnant waitress to take my bacon double cheeseburger order, and even longer for it to arrive, I no longer had any rush to go anywhere. I could sit here for a few hours, like the old men, and wait. Border agents drove slowly through town several times and the old men noticed. Must be looking for someone, they said. Cathy's shut down at 2 pm for a break during the afternoon. I didn't finished my last onion ring until nearly 3.

I wandered over to the Washington Hotel, right next door, to see about a room for the night, for I was hot, tired, and wanted to shower and sit on something soft for a while. And mush-up my brain with some television. The Washington was old and looked like it dated from the Grant administration. After knocking for a while, an old woman, stooped with age, walked slowly to the door and promptly told me that she had no rooms. I was devastated. I was looking forward to a shower and a sofa so much that I didn't know what to say. I muttered something about being on foot, having nowhere else to go, about having walked here from the Rockies. She looked at me a closely and told me to come back later, that she was getting ready to take her bath. That sounded favorable and I told her I'd go to the park and come back in forty minutes.

Metaline Falls is not a large town and this was the only option in town except for an apartment complex that reportedly rented out rooms by the night. After sitting in the shade in the park for a few minutes, I decided to investigate and see whether or not that might be an option incase the old woman decided not to let me stay the night. I walked through downtown Metaline Falls, which took about two minutes. Most of the stores were boarded up and the town was clearly dying. There was a general store and a grocery store. A post office. A movie theater open on the weekend. A bar. I found the Miner's Hotel on the far side of town and a first it looked like a grand place. But as I got a closer, it quickly lost its charm. I walked inside and a note on the desk asked prospective clients to call a number for a room. Since I didn't have a phone, and didn't like the look of the place, I left the decaying building for the clean air outside.

I walked back to the park and had a sit in the shade, wondering what I should do now that I'd ruled out the only other option in town. There was a sister town called Metaline about a three mile walk from here where there may or or may not be a place to shower and rest. After thirty minutes I saw the woman open the door and spy me sitting on the bench. She waved me over and I quickly crossed the ground to learn my fate. There had been a wedding in town and non of the rooms had been cleaned yet, she said. I countered with a story of my usual bedroom and added that I could easily change the linens myself. "You look pretty wore out," she said, "come on in.". And this was how I met Lee McGowan. She gave me pillow cases and sheets and told me to take the room at the end of the hall upstairs.

The Washington is old, but had charm. It had style. It was built out of wood and there wasn't another building like it in the world. It you go to one Motel 6, you've gone to every one. And every Holiday Inn. And every Best Western. And any other chain. All that changes is the price. It was pleasantly cool inside, courtesy of fans and open windows and lots of shade. I found my room. It was small, but with a bed, a chair, and a view of the park. I quickly dropped my pack and went back down the stairs to the store, where I bought some beer and a newspaper to celebrate away the afternoon. Back at the hotel I took a can of beer with into the communal bathroom and had a very well deserved shower, complete with soap and shampoo. It was my first proper shower, in fact, since leaving Lakewood, for the shower in the city park in Eureka didn't qualify. I drank beer in the shower, and then while washing my clothes in the sink, and felt euphoric at my clean skin and oil-free hair.

Laundry done, I sat on the bed and drank another can of beer while leisurely reading the paper. I didn't care so much about the news. I just wanted to hear about some one else, some one other than me. I didn't want to contemplate only what was around me and in my head. Rather, I wanted someone else to focus on, some other place, some other time. An hour passed in the cool darkness of the Washington. I was the only guest and Lee was the only staff. A cool breeze wafted through the window of the room as I lay on the bed sipping beer and reading. At some point I drifted off to sleep and dozed in sweet unconsciousness for an hour.

When I awoke I was hungry and out of beer. I dressed and walked downstairs where I found Lee watering some plants. She smiled at me and told me that I looked much better now that I had had a shower and was healthy again. I grinned and chuckled. "You looked pretty beat when you got here. Amazing what a shower can do." I couldn't have agreed more. I stuck my head in the bar but the smell of the place told me to go elsewhere for dinner. I hit the store for more beer and a feast: Raw vegetables for a salad and a jar of garlic pickles. Back at the Washington I sat in the common room watching television and eating. I ate salad for a long time, going through several cook pots worth, and polished off the pickles along with several large cans of strong beer. I stayed up as late as I could, for I didn't want the night to end. I wasn't doing anything that any one other than myself, or any other long distance hiker, would have recognized as being enjoyable. But I was clean, had raw vegetables to eat, something soft under my backside, a beer to drink, and something to occupy my mind without any effort on my part. And these were luxuries. This was luxurious living.

The soft bed had not done me well overnight. I had slept fitfully, uncomfortably, unused to the softness and the give of the mattress. But the soft light of the early morning was a sign that I had in front of me that sweetest of all days: A zero day. A day in which to do nothing but eat and rest, to enjoy town for all that it was and all that it held. I padded down the hallway to the bathroom and took a lengthy shower, even though I was still clean from yesterday's shower; it just felt good to scrub my skin again. I dressed and wandered outside to Cathy's, where I found a few tables full of locals eating and chatting. And the same two old me sitting out front, as if they had never left. They were still talking about high school sports. The sausage, jalapeno, and cheddar omelet, along with homefries and toast, was enough for a normal person for an entire day, but for me was just right in the morning. I drank my usual, for a town stop, eight cups of coffee and read the paper, this time from Spokane instead of Missoula. I didn't think there would be a hint of Seattle until I crossed the Cascades.

I swung by the post office on my way back to the Washington to pick up my bounce bucket and had a nice conversation with the woman behind the counter. The staff at the PO had been wondering for some time who this Chris Willett was who was hiking into town and had mailed a 5 gallon paint bucket to himself. What was this PNT thing, she asked. We chatted for a while, for neither of us had anything especially important to do with the day. Metaline Falls was like that. I returned to the Washington and had a seat in the common area with the maps and guidebook section for the upcoming run to Oroville. And to ogle the cleaning woman who was working to straighten up after the wedding reception over the weekend. The feminine softness that she exuded was something that, it occurred to me, was at once both completely absent from a long hike like mine, and yet strangely at the core of the experience. Softness, tameness, domesticity, these things were unknown to a life out-of-doors. Yet, at the same time, the notion of a nurturing, fertile Earth was something that I experienced every day out here. Both were part of the Feminine. Absent and present at the same time. I watched her move about the room in the way that only women can and thought these things. I made a mental note to think about the masculine aspects of life out-of-doors at some point in the summer. The obvious was there. Where was the un-obvious?

I napped for a while and then went to the store, for the third time since I arrived in town, for supplies for the short hop across Abercrombie Mountain and down to the Columbia River. The Columbia was, for me, very symbolic given its role in the settlement of the Pacific Northwest. Indeed, it is The River of the West. Once I crossed it, I would be almost at the Pasayten, and hence the Cascades, and hence home. My chores done, I set out to see more of Metaline Falls, for I suspected that if I ever had children, they would not be able to see it the way I had. It would be dead by then.

The visitors center was the first stop on my tour. It was empty, open to all. Aside from masses of used books for sale, there were many photographs on the wall documenting the early days of the town and the region. Like many towns in the West, Metaline Falls, and nearby Metaline, was founded to extract something from the land. Either digging in the earth or cutting down the seemingly limitless trees, the economy of the region was based upon the natural resources that it held. The Pend Oreille river provided convenient transport to and from the region, and many of the photographs on the walls were of steamships loading and unloading. As with most of the rest of the West, large swathes of land came under the control of a few small interests and logging became a way of life for many. With the loggers came the most aggressive of all trade unions, the IWW, who successfully improved the lives not just of the loggers, but also of the miners.

The area slowly began to be settled by individuals and families, though the isolation of the area made it less attractive than regions further to the south, such as the Palouse, now one of the breadbaskets of the United States. As time progressed, the resources began to fail and other, more accessible regions became more popular. What little capital the area was able to generate tended to flow outside of it, to large, established corporations. Cement and dam building generated revenue, but these were not to last for very long. A mining boom during the World War II era provided some hard cash, but this, too, was not to last. Perhaps 200 people still lived in town and, judging by the closed buildings and abandoned homes, the town itself would not last much longer.

I sat in the dugout of the local ball field and thought about places like Metaline Falls. The field hadn't been used in some time, for there was grass growing through the base lanes and the entire place had a general sense of un-use. People might still gather for a barbeque, but it was unlikely there were enough young people left in town to field two complete teams. When the end came, no one would be around to mourn the passing of an entire way of life. No one would even notice. What difference would it make to someone in Seattle, or Miami, or Los Angeles, or Chicago, or anywhere urban that a part of their heritage was gone? None, for they didn't even acknowledge its existence. The last generation that had grown up on the frontier was passing away, and with them they were taking all they knew, all they had experienced, all they ever were. I sat in the shaded dugout and thought.

It was hot out in the mid afternoon and I felt like having a beer to mourn the passing of Metaline Falls. Back to the store I went, back to the same woman behind the counter who called me Guy, back to the fading Washington Hotel. When Lee passed on, the place would go to the hands, most likely, of her daughter. I didn't think it would last very long. I sat in the common area where it was cool and drank two cans of strong beer while watching television and thinking. I was glad that I had spent time in Metaline Falls. Unlike Eureka or Bonners Ferry, it didn't seem to have much of a reason to exist any longer. I would never have come here had I not been on foot, for there was nothing to see in town, no tourist attractions, no national parks, no big mountains. The only reason to come to Metaline Falls was for a look at the past before it disappeared forever.

I took another nap to sleep off the beer and then went out in search of dinner. I found Lee down in her studio and settled in for a chat. She didn't charge me for the first night, which I thought rather generous. We talked about my walk and the area. She used to roam the hills around Metaline and Pend Oreille county in her youth, but she no longer could and contented herself with her memories and what she could see from town. Lee looked to be in her 80s, but her mind was still clear and her thoughts and words lucid, as if they were ignoring the advance of time that was strangling her body. I wanted to know about her youth, about the early days in the county, and the WWII days, and the wobblies, and the closing of the cement plant, and the future of the region. I wanted to open up her mind and take out everything that was there, to record it for the future, to preserve it against time. But this isn't possible. I'm not a historian and she isn't a specimen.

I went back to the grocery store where the same woman again called me Guy, but finally ventured to ask if I was coming in to work at the dam. This sparked a short conversation about living in the area and what people did. The dam, which I'd be passing close to tomorrow, provided power for Seattle, and a few jobs for locals. But the skilled people and the managers all seemed to come from outside the region. Whether or not this was true, it seemed a small reason, but still a reason, why the town might continue to live for a little while longer. I bought some food for dinner and retired to the Washington to drink beer and watch whatever happened to be on the television set. The night progressed. What would be here in ten years? I doubted the Washington would still be operating. The grocery store, perhaps. The sewing shop that doubled as a liquor store? Maybe half of it. The theater would be gone. Eventually the post office and elementary school would close. The two old men would still sit out front of Cathy's and talk sports. And I would be sitting in another small town in the middle of nowhere, a town that had a history, and be mourning its slow death, just like I was mourning Metaline Falls tonight.

t was cool in the early morning when I walked out of town. I had gotten up early in the morning to eat a last breakfast at Cathy's before starting the push to Northport and the Columbia River, only forty some odd miles in my future, though a very large mountain stood in my way. There wasn't much happening in Metaline Falls in the morning, with only a few locals eating breakfast at Cathy's and a few vehicles on their way out of town heading to work in some other place. I stopped in the middle of the bridge over the Pend Oreille river and enjoyed the view up and down stream. There something about rivers, about all flowing water, that is calming to me. Calming isn't the right word. Reassuring, perhaps, is better.

I wasn't officially on the PNT, but that didn't matter much. The PNT took roads, also, to get to the trailhead for the climb over Abercrombie, only it did so without going through Metaline Falls. Since nearly every hiker would want to come into town anyways, I didn't see the point of the PNT in this valley. A few cars passed me as I walked along the side of the road listening to NPR and enjoying the cool morning. Dogs would occasionally rush out at me and I'd have to either chase them away, face them down, or make friends with them, depending on the dog, of course. I turned off SR 31 and took the high road, unimaginatively named Boundary Road. More dogs. I began to wish for pepper spray. Boundary road returned me to near Metaline Falls and gave great views of where I had just spent the last day and a half.

My route was going to be an easy one, I figured. Once I got to the trailhead, I'd have to climb hard up and over Abercrombie, gaining more than 5000 feet in elevation and should be rewarded with superb views of my past and my future. Then, down to Deep Lake Road. I could continue on the PNT, which seemed to consist of old road beds passing through the woods, or hike up to the border of Canada and meet the Columbia where it enters the US. A big road would lead from there to Northport. Although it was longer, I liked river walks and decided to head there. After an hour or so, I spied what I thought was Abercrombie, way up in the sky with a rocky, desolate top. Surely the trailhead would be close.

I hiked and on and never found the trailhead. The description in the book could have been in many different places and, as far as I could tell, there had been no signs. I had gone up several promising spur roads only to find them gated and closed with No Entry signs posted courtesy of logging companies. I took a break in the shade and realized that I could just keep going to the border and follow a forest service road up and over the divide and down to the Columbia. Never walk backwards! I soon passed the turn off for the dam, where the PNT comes in, and kept heading north. I entered Crawford State Park and found my forest service road right where I thought it would be and began the climb to the divide.

Twenty minutes after starting up, I saw the truck. White paint, green and brown trim. Border Patrol. Crawling down in low gear, the truck slowed to a stop as it neared me and the agent inside grinned and through out a friendly, "Howd-ee". The agent looked like Richard Petty in his prime, complete with wide sunglasses, a cowboy hat, and a big grin. He even had a southern drawl. I noticed that while his left hand was on the wheel, his right was on his gun. In our entire ten minute conversation he never seemed nervous or threatened by me, but his hand never left the gun. My hands stayed on my shoulder straps where he could see them. Despite his friendly manner, I was definitely a bit intimidated by this and answered his questions as quickly as I could in the most direct manner possible. Always friendly, always polite. Hand always on gun. I was happy when he continued downhill, away from me.

The skies were clouding up as I crested the divide and I realized that it was, perhaps, fortunate that I had not been able to locate the trailhead to Abercrombie. If a storm was coming, I would have seen anything anyways and would have been rushing to get back down below tree line. Walking the forest service road required a certain amount of faith that things would work out for the best. My map showed a single road, but logging operations had clearly changed that and many spurs came and left. Most of the time it was clear that they went to current or former cuts, but other times I was faced with a fork and no obvious choice. Since I had no way of making a good decision, I just went and tried not to think about getting lost. Eventually I began to descend to the Columbia side of the divide, though the clouds still hung in the valley below me and I could not yet see the River of the West.

For some reason, the girl in pigtails came to mind and I spent a while thinking about her and where she might be at this time. Probably out hiking on the island, or maybe working at a coffee shop getting ready for school in the fall. If she had driven by at this moment, I wasn't sure if she would recognize me unless I said something to her. A soft rain began to fall as I wandered down the road and I had to stop to put my rain jacket on.

Logging is one of the lifebloods of the West, especially the Pacific Northwest. It sustains people in places where there are no other options for making a living other than resource extraction. I know this, but I still feel a sense of depression when I come upon a logged out area. The slopes barren and filled with scrap, a few remaining trees left standing to help re-seed the land. Nature is beautiful in all of its aspects. Even Kansas. What is ugly is what we do it. It is the ugliness that strikes me and all I can do is hope that the logging is being done in a sustainable manner and is supporting people who live in the area, as opposed to making fat cats even fatter.

I rain slowly faded into a mist that seemed appropriate for the land I was walking through. I pulled up at a roadside culvert where a creek flowed down and underneath the gravel road. From the inside of my pack I pulled out my stove and olive can stove and a ziplock bag that held macaroni and cheese. I poured some methyl alcohol in and started heating the water for my feast. Nuclear orange colored powder mixed with olive oil and some of the cooking water turned into a sort of sauce that had been advertised as being cheese, but resembled something else completely. What it was, I didn't know. It was a thing unto itself. I never eat the stuff when I'm at home, but it somehow managed to taste good out here. It tastes good only when I'm out there. I spent an hour by the side of the road before starting down the hill once more. I wasn't planning on hiking much further, for I did not want to reach settled areas and have nowhere feasible to camp. Whatever happened, I didn't want to reach pavement before camping for the night.

I stood, two hours later, at the Deep Lake junction looking at the houses around me. I had come out of the mountains and entered directly into settled lands, where homes and dogs were everywhere. And not vacation homes these, but rather homes where I could wave to someone on the porch drinking a beer, waiting for their own supper. I had to keep going. I wandered down the road for another hour and realized that, though I might be able to stealth in the woods, I had no more water and thus had to keep going. But, I realized, the Columbia was close! And so I kept hiking on, in sight of the mown strip of the border.

Deep Lake Road curved around the last bit of mountains and dropped me down into the Columbia valley. The river was there, at last. A road split off and went to the border, though a sign indicated that it closed at 5 and it was now 8. I walked down the deserted road to a store, but it, too, was closed. A beer would have been nice, I thought. I continued down the road with not a single car passing me. A few isolated houses were set far back from the road, but no activity could be seen in them. I was, it seemed, completely alone. It felt odd, like being the last person left alive after some terrible virus wiped out the human race. I followed the Columbia for another thirty minutes, then dove into the woods, passed some No Trespassing signs, and crossed the Burlington Northern railroad tracks on my way down a faint use trail. A flat spot with a view of the river greeted me. I was home for the night.

I went down to the river and fetched water and began to filter it. While it was dripping through my gravity filter I wandered around camp, declining to set up until after dark, which would be soon. I was technically trespassing on railroad property, but the various boats and clothing and other detritus that I found along the shore, as well as the use trail, indicated that locals came down here frequently. Still, I didn't want to press my luck. I couldn't be seen from the road, but I could from the railroad. I found a large feather, presumably from an eagle, and was inspecting it when I heard a voice. Not talking to me, though. To someone else. I looked around and saw a figure on top of the ridge where the railroad was, talking on a radio and looking right at me. He didn't come down, or say anything to me, which worried me a bit. I couldn't make out the uniform he was wearing, for dusk was falling and he was fifty yards out. I couldn't believe my bad luck! For some reason railroad security must have been in the area and spotted me going across the tracks. It was a million to one, but there it was. At the very best I'd get off with only a talking to. At the worst I'd get a beating and then get hauled to the local jail. I stood and waited.

After a few minutes his partner showed up and they began their assault. I was eating a Snickers bar to calm myself a bit as they began crashing through the woods in a pincers movement. I chewed some nougat and hoped for the best. Then one of them yelled out, "Hello! We're with the border patrol! Don't move!" I was rather relieved to see my old friends once again. The two agents, complete with military looking assault rifles, continued their struggles through the woods, declining to take the path down to me. I stood stock still until they arrived.

Agent 1:"What are you doing down here, sir?"

Me:"I'm getting water from the river." (pointing to my water bag and filter)

Agent 1:"Hmm. Makes sense. Did you cross the border, sir?"

Me:"No, I came down Deep Lake Road."

It seemed that they realized right away that I had not just snuck across the border and that I was no threat. My pack was too small to be smuggling anything important, but as they were here and had gone through the trouble to find me they decided to go through the routine. I had to put my hands on my head (and interlock my fingers, I was reminded) while Agent 2 patted me down for weapons or drugs or a nuclear bomb. My pack was searched ("Anything in here I should be aware of, sir? A knife you say? Why are you carrying a knife, sir?"). I had to witness them opening the ziplock where I carried my cash and documents to make sure, as they said, that nothing went missing. My drivers license was called into their headquarters and we began the wait. By this time they knew that they had assaulted a hiker trash camp and were not going to find anything special. No anthrax here! I told them about my route today and before, and where I was going. I told them that I had hiked from Mexico to Canada before, shocking them. About a lot of things, including the fact that there was proposed National Scenic Trail that would be running right through here.

As we waited and chatted they got friendlier and friendlier and seemed genuinely interested in what I was doing out here, not from a law enforcement standpoint, but rather from a human one. Why was I doing it? Where did I sleep at night? Where did I get my food from? Did I really hike in running shoes? I asked how they had found me so quickly. A citizen (their term) had seen me walking down the road and thought it was suspicious, so they called it in. There was a house across from where I ducked into the woods and that was how they located my not-yet-set up camp so soon after I had arrived. I told them of my other encounters with the border patrol and that I was surprised there wasn't more information sharing about a hiker moving through the region. It didn't work that way, they said. Each office is on their own and they don't file a report unless an arrest is made.

The all clear came back from headquarters that my license was clean and the agents walked back up the trail after saying goodbye. It bothered me that I was regarded as such a threat, but this is the nature of being on foot and without many possessions. Roads can be controlled, but borders cannot. Still, what would have happened if I didn't have a drivers license? There is no requirement in this country to carry an identification card. So what would have happened? Would I have been detained until my identity could be verified? How long would I have to sit in a holding room until they sorted all that out? Would they have bothered, or only questioned me thoroughly? Did they even have that right, or could I refuse to answer their questions? I'm not a lawyer and didn't know.

I set up camp in the pitch dark night and crawled into my sleeping bag to write for a while in my journal by the light of a small LED that I had bought back in 2002 for my first long hike: 450 miles on the Appalachian Trail. That had ruined me back then, and it was still paying dividends today. I had covered more than 35 miles today and had only, perhaps, another eight to go to reach Northport tomorrow. There were rumors of a brewpub in town and a free park to sleep in, though the border agents didn't think it was a good idea, since that was where all the local youths went to do wheelies on their motorbikes and smoke grass. I turned off my light and thought about the encounter that I had had with the agents and the citizen who had called me in as a suspicious character. Malcolm X once said that the most dangerous thing in the world was a person with nothing left to lose. I had experienced this before, on other trails, in other places, when families, or big strong men, clearly saw me as a threat precisely because it looked like I had nothing in the world except for what was one my back. It was disturbing, but it was also to be expected in modern society. The stranger, the other, was danger. It was the antithesis of everything that I wanted out of the summer. I didn't want to cut myself off from those I didn't know or were afraid of. I wanted to put myself out there, to have experiences, to live without the benefit of a safety net. At least as far as I could. I wasn't Jason and would never be him. I didn't want to be him. But I wanted to live in openness where there was the possibility of something great happening, but also the possibility of something painful, like a beating at the hands of railroad bulls. I closed my eyes and hoped for the future. Not just tomorrow, or next week. But when I got home. I hoped that I would remember. That I would not forget.

My eyes flicked open, my senses on edge immediately, telling me something was happening near me, something that I needed to pay attention to. It was pitch black out and raining softly, the tump-tump of rain bouncing off the taut tarp playing sweetly in my ears. A snort. Another. A big wheezing snort. I frowned and went back to sleep, for I wasn't especially worried that the deer whose spot I had taken for the night would try to evict me. I slept until it began to get light out and then emerged from my tarp to begin my short haul into Northport.

The air was humid and misty, giving the land a spooky look to it that magnified the emptiness of it. There were no cars on the road. It had been deserted last night while I strolled down it, and now in the morning it was equally deserted. Had it not been for the visit from the border patrol last night I would have thought that no one lived in the area or even drove through it on their way to somewhere else. I was me and the grass, the road and the rail, and nothing else. My feet had been sore for the last few days, but they were especially bad this morning, with hot spots developing quickly underneath my heels, The humidity of the air caused a sweat to break out quickly on my forehead and a long uphill climb onto a bluff soaked me completely.

The road ran along the top of the bluff and provided nice views down to the Columbia and to the small farms in the vicinity. After two hours, I could still count the number of cars that passed me, in either direction, on one hand with room to spare. The mist began to lift and I could feel the air drying out. I was sorry to see the somber mood leave the Columbia, but by doing so it did bring out a really nice view from the top of a road side boulder lavishly decorated with graffiti. Northport was finally in view. A small collection of homes and businesses clustered on the east bank of the river, a long bridge connecting it to the rest of the world. Directly in front of me was the boat launch and city park, where previous hikers had camped and where the border agents had warned me to avoid. It looked so-so from here. At 9:30 am. Not knowing where I would sleep tonight was part of the day's fun.

As I neared town the traffic on the road began to increase, but only slightly. Like Metaline Falls, Northport was small and decaying, though its downtown area still held some promise. Like Metaline Falls, it had been founded on a big river that provided convenient access to various points to the south and, across the border, to the north, where the Columbia provided easy access to some of the gold fields of Canada. Like Metaline Falls, it prospered initially by extracting resources from the land and then fell on hard times when easier, more lucrative regions opened up to be exploited. And now it was just hanging on.

The first building I came to upon entering town was the Mustang Grill. Perfect time for breakfast. I sauntered in and dropped my pack at a table in a far, lonely corner and ordered a cup of coffee while I perused the menu. I do this every time I go to breakfast, but always end up ordering the same thing. Omelet of some sort, hashbrowns, wheat toast. The only difference comes when I'm in Canada. Then I order brown toast. There were a few locals hanging about drinking coffee and reading the newspaper or chatting with the pretty, very pregnant waitress. The omelet that came to me was rather disappointing, which surprised me because the bread was outstanding. This wasn't made by a machine somewhere. Rather, the thick slices came with a crunchy crust studded with seeds that only a pair of hands can make. I thought about trying to buy a loaf from them, but got distracted by some locals who gathered up the courage to ask me where I had come from and where I was going.

I told a small crowd about my trip so far, where I was heading and by what route, where I had come from and how I gotten here. And then I started the Yogi. To yogi something is to get someone to offer you something you want or need, but don't want to come out and ask for. For example, you happen upon a hippy picnic in the San Bernadino mountains while hiking the Pacific Crest Trail and the smell of cheeseburgers grilling over open coals just drives you mad. It would be impolite to simply come out and ask a stranger for a cheeseburger. So, instead you strike up a conversation about hiking, the mountains, how pretty it is, and so on. And then you mention that you're hiking from Mexico to Canada. Wow! They're impressed now and want to hear more. You tell them a story or two and they naturally feed you a burger. Everyone is happy with the arrangement. You just yogi-ed a cheeseburger. You can do the same thing with rides into town by chatting up hikers on their way out. The ethics of yogi-ing are debated widely by people who like to argue more than hike, but as long as you don't press people, beg, or make it a habit, it isn't a problem.

And so I began the yogi. It starts with a simple question, "Is there any place inexpensive to stay in town?". Now, I know there is no place inexpensive to stay in town because I've already seen the whole town and the only motel in town had clearly been closed for a while. Moreover, I've just come out of a zero day in Metaline and spent two nights in a bed. I'm actually just looking for a safe place to camp for the night. The motel is closed, I'm told. There are cabins for rent, but they're pricey and outside of town. The B&B is $50. I put on my disappointed face and thank them, but money is tight and I have a long way to go to get to the Pacific. "What about the camping down by the boat launch in the park?" To a person, they all look askance at this and tell me about kids doing wheelies and getting high down there, just like the border agents did. "Well, I'm sure I'll figure something out." I thank them and start to leave. This is how I met Joe.

Joe continued the conversation on the way out of the Mustang Grill and offered me a place on his lawn to camp. He lived in town, about 1/2 mile from here, and had plenty of space for me to set up my tarp on. He was finishing his breakfast and I needed to resupply, so I told him I'd meet him at the grocery store in a little while. We were both happy with the arrangement. Joe gets to do something nice for a complete stranger and earn some merit. I get a place to camp for the night where I don't have to worry about weed smoking teenagers doing wheelies. I strolled to the store, just down the block, and bought some supplies for the run to Republic, along with some post-breakfast treats. Joe was chatting with the store clerk and I suspected that everyone knew everyone else and their children, their pets, and the names of their cars. Joe drove back home and I mentally made notes of landmarks along the way so I could get back into town, for I had a date with the local brewpub (God bless Washington) at 2 pm when it opened. I told Joe a few more stories from the trip to help repay my debt to him and set up my tarp in a cleared spot on his lawn.

I spent the next three hours repackaging food and looking at maps and the guidebook, listening to the radio, and eventually just laying on my back looking up at the clouds rolling by the and the sparrows roosting on the power lines overhead. A nine year old boy came over on his bike to investigate me and what I was doing on Joe's lawn. Joe, you see, was a friend of his. The boy and I quickly became friends and I learned about the doings and happenings of Northport before his mother hollered at him from down the street. I napped for a bit and then freshened up as best as I could for my date. I detoured on my walk back to the brewpub to see what was going on in town. The main drag was still healthy. Off of it was dead. Not dying. Dead. Weeds, rusted out buildings. A bar with the town drunks hanging out. I hustled to my date.

When I walked in I was the only person in the brewpub except for Steve, the bar tender, brewer, server, and owner. I ordered up a Pale Ale and settled in to find out what I could about Steve and Northern Ales. For the sake of accuracy of my narrative, of course, not because I wanted to sit in the brewpub for hours drinking multiple pints without the responsibility of a car or of even making it home at night. Steve and his wife had opened Northern Ales two years ago when they moved out here from San Diego and needed a way of making a living and contributing the local economy. Steve had been in the navy before coming out here and it seemed somewhat odd that a sailor from San Diego would end up in the middle of nowhere Washington, far from the ocean. It seems they were looking to move to the middle of nowhere and a town just south of Metaline Falls called Ione seemed about as far as they could get from anything. Property was cheap and they could have a spread of land to themselves. They came out to look in the winter and roads were blocked with snow, so the realtor brought them over to Northport instead. I ordered a pint of brown ale and continued my research.

Although I now knew the story about how Steve and his wife came to be in Northport, I didn't know the why. The why is always the most interesting. Why would a sailor leave San Diego for the middle of nowhere? Although I could imagine all sorts of bizarre reasons, the true answer was probably the same one that brought me into Northport. I didn't know Steve well enough to ask. Instead, I ordered up a pint of smoked porter and asked him about the local economy and how people made a living in Northport. Many retirees, it seemed, simply fled the area when the winter arrived and came back when spring was in full swing. He remembered Mule from last year and we chatted about the PNT. Can't talk about hiking without drinking, so I ordered a pint of Old ale to go along with trail talk.

By this time there were another couple of people in the brewpub and I was pretty loaded. Steve didn't have a set up to make food here and so had the Mustang Grill cook up pizzas for him and bring them over. I happily ate a large supreme and washed it down with a Scotch ale. My investigation into the brewing scene of Northport was ready to wrap up, for I didn't think I could finish off the remaining three beers on the menu without having a severe bodily reaction. I thanked Steve again and wandered down the road back to Joe's house and my tarp.

I laid out in the grass and watched the sun set, listening to CBC and drinking a can of beer, and was filled with a sense of great personal fortune. It wasn't just the five pints of beer that I had drunk at the brewpub. I had been thinking about it for the last few days, last couple of years. I am blessed to be healthy enough to be able to do these sorts of things. I am blessed to have the kind of job that allows me to work only part of the year, yet retain benefits and position. I am blessed to have the mental desire to do such things. And I am blessed to have the drive to actually make them happen. I'm the most fortunate person that I know, even more so than Bill Gates or Tom Brady or Hillary Clinton, though I can't claim to know them. I hoped that I had developed enough on the inside to deal with any change in my fortune. The loss of a limb. Going blind. Spinal cord injury. Getting fired. Getting married. Becoming tame. I didn't want to lead a life where I could only read about or think about what was out there rather than actually going and finding out, experiencing it for myself rather than through the lens of another. I wasn't sure how I would be able to live if I had to give that up, for what ever reason. I would have to at some point. Old age, sickness, and death would eventually find me. My desires would change. What was important to me would change. And I would have to adapt. But for now I was able to lay in a field of grass and look up at the stars and consider myself the wealthiest, the most fortunate, person on the planet.