The Places In Between

Northport, WA to Oroville, WA

July 31, 2008

I hate it when my nose gets frosty. My body, deep in my sleeping bag is warm, while my head, covered by both my hat and the hood of the bag, is toasty. The hood is cinched down and all that is exposed to the open air is my nose, which is cold, and that is unpleasant. Putting my nose inside the bag only works for a minute or so, before the air gets too stuffy. And so out it goes once more and the cycle repeats until, frustrated, I get up and start the day.

Joe was up drinking coffee and looking out the window when I set out across the frost covered grass. I walked quickly down the street to generate some heat and by the time I reached the gas station by the bridge across the Columbia I was feeling pretty healthy, despite all the beer I had drunk last night. I stopped inside for a pasty and a cup of coffee. Both were so wretched that, after a couple of minutes of sitting on the curb eating and drinking, I threw both away, neither even half way done, and set out to see what the day held for me.

The Columbia is the heart of the Pacific Northwest in many ways. It sources high in the Canadian Rockies (I hiked right by it when I traversed the Canadian Rockies back in 2004) and flows down the western slopes, eventually running south, and entering the US near where my camp had been raided by the border patrol. It then runs across Washington and down to the Oregon border, which it follows through a deep gorge, penetrating the Cascades, and ending at the Pacific. Along the way it flows through the classic alpine terrain of the Rockies, past the rich farmland of southern British Columbia, across the arid, volcanic desert of central Washington, and into the rain forest of the west slopes of the Cascades. Before it was dammed all to hell, Salmon swam up it for many miles to spawn in other side rivers. But, we decided to trade this natural resource for cheap electricity and inexpensive wheat and apples. It is the river of Lewis and Clark and David Thompson. In a land of rugged mountains, it was a highway that could be cruel to those unprepared, but a godsend for those with some skill. A canoe and some time, I thought. That would make a nice trip. Just me and the Columbia and many six packs of beer.

I crossed the bridge and quickly picked up the side road that I was going to take over the local mountains and down to the Kettle River on the other side. Sheep Creek road was the official PNT in the area, but that didn't mean much. The PNT wasn't a National Scenic Trail. It didn't have any official status except for what the PNTA said it had. But it was the most logical route through the mountains and so I followed it as it followed meandering Sheep Creek toward the peaks in the distance. A car passed me. A second one. The third wouldn't pass me for several hours. The heat of the day began to build and I thought about the girl with pigtails to pass the time on the hot road.

Sheep Creek led up up to a minor pass and more logging operations, operations which, though they provided jobs, devastated the land for generations to come. The people who cut down the trees here will have less space to hunt in and the game will be scarcer because of it. I diverted over onto a smaller side road that clearly saw nothing but ORV and ATV traffic, and little of that. The day, though, was sweltering and I was low on water. A source in the guidebook failed to materialize and I began to worry a bit about my health. If the next was dry, I might be in trouble.

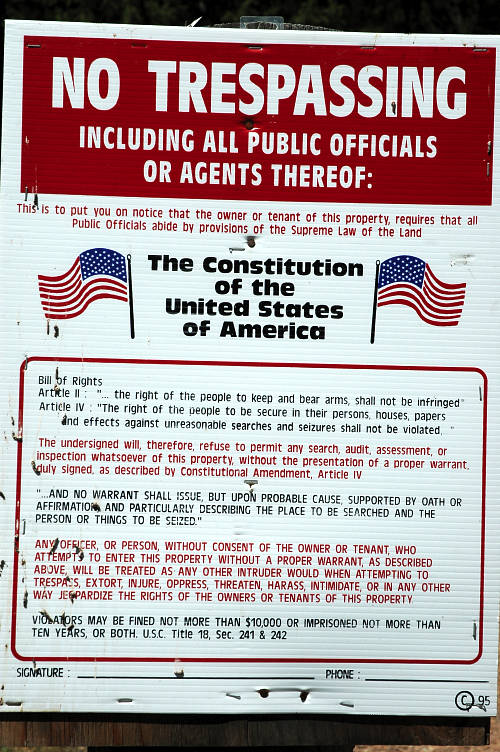

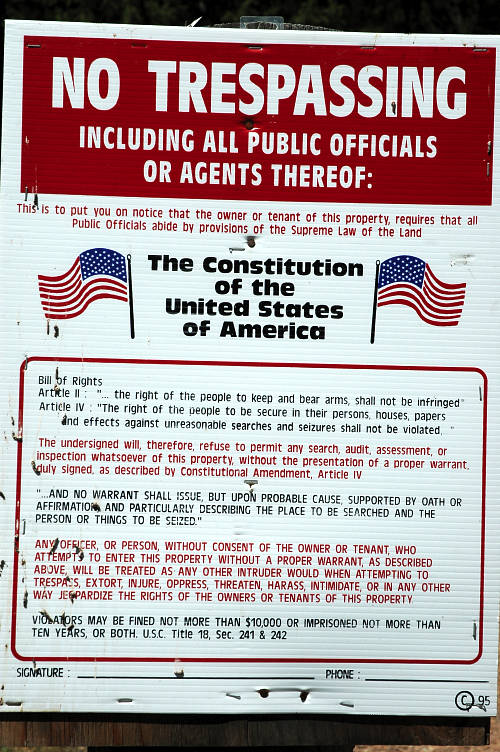

The road dropped down off the plateau and immediately came crashing into private property. The signs started. Keep Out. Beware of Dog. No Trespassing. Visitors on foot were so rare here that the signs must be for hunters in the fall, rather than for the two or three, or no, hikers that came through every summer. I was parched by the time I arrived at the creek where I was hoping to get water. It was dry. I wasn't sure if it even was a creek, for it didn't seem to have flowed any time soon. I sat in the shade and had the last few drops in my water bag, not that they would do my sun addled body much good.

I continued down the road, now called Sand Creek road, and began passing homesteads and farms, complete with charging, snarling dogs and a few old men sitting by their trucks chatting. It is a sign of development to be able to ask for help. It shows that you recognize the difference between pity and compassion and are able to quiet your ego long enough to help your body. I kept on walking without asking for the water that I so badly wanted. Just a bit further, I said. Almost to the river.

I passed the old men and the dogs and kept on down the road for another mile or two until it finally reached the Kettle River. A large sign was posted. Keep Out. Private Property. No Trespassing. I gave the sign a kick to move it out of the way and went down to the river to fill my water bag. The last I checked the rivers of this country were free resources to all. The Army Corps of Engineers maintained the dams and controlled the floods and the river did not belong to some private individual for their own benefit and amusement. I wasn't planning on camping here or building a home or having a party. I wanted water.

I gathered the water and guzzled down a liter immediately. I had come 23 miles from Northport through the heat of the day on two liters of water total and badly needed to rehydrate. I drank another liter, then refilled my water bag for dinner. A patch of shade twenty feet back from the road in the woods provided my dining room for the evening and as my water boiled I pondered the nature of private property and its tradition in our country and the rest of the world. There is a fundamental difference between owning, say, a pair of pants and calling it private property, and owning a river. Or a tract of land. Or a mountain side. In between was the grey area that was so hard to define. Homes, for example, sat in this grey area. People needed places to live. But was there any need for a 5000 square foot trophy home? Although it wasn't important to me, it was hard, if not impossible, for me to say that it was absolutely not important. As long as that home didn't interfere with other people, it was fine. But when it cut off access to, say, a lake, it was a problem. The Kettle River was the property of all. Its water should not be denied to those who need it to live (agri-businesses are not people), nor should access to it be restricted. If you choose to build your house on its banks, you need to accept that people will have to cross your land to get to the resource that they need.

I finished dinner and rested in the shade, then turned on my radio to listen to the Spokane Indians baseball game, which seemed to come on every night. It was nice to listen to the radio while on the road and it made the climb up the other side of US 395, past many No Trespassing signs, much more pleasant. The air was cooler out than it had been and walking was again becoming something pleasurable to do. I gathered water at a spring a mile or so from the river and started looking for a place to spend the night. Finally I found a spur road, long abandoned, that I could hike down and camp on. It was quiet, out of the way, and I was pretty sure I was still on national forest land. It wouldn't bother me a lick to be on someone else's land for the night, but I wanted to respect others' rights as much as I could.

This was important, I thought, as I wrote in my journal. It was important for me to respect private property rights until they interfered at the most basic level with my survival. I had to sleep somewhere tonight and, even though my hiking range is extensive, it might be the case that I found myself, one night, surrounded by nothing but private property. And what then? I would practice strict Leave No Trace rules, set up when it was dark, and be gone in the early morning. No one would ever know that I had spent the night on their land. I was not trying to formulate a universal law of behavior while sitting in an ivory tower. I needed a place to, as Jason would say, "lay my neck for the night". Or, a drink of water to fight off sunstroke. Or a place out of the rain to avoid hypothermia. Your right to private property ends when survival is at risk. But so does mine. Smarter people than I had pondered this very issue and had written extensive treatises on it. But it ignored the individual nature of survival. This afternoon I had needed water. Simple water. I ignored a (probably) illegal private property sign because I needed water. Just water. I wasn't a communist coming to take away a truck or a rifle or a plasma TV or the American flag. All I wanted was a drink of water.

It rained heavily overnight, but I stayed warm and dry under the tarp and awoke to find the the clouds gone and the sun shining. I went through my morning routine of tea, breakfast, and a look at the maps. I had roadwalking in front of me for most of the day, though it would end at the start of the Kettle Crest National Recreation Trail, a route that I had been looking forward to for the last few days. The PNT takes an odd route through the Republic area. The route maps a long U shape, with the town of Republic in the center of it and the Kettle Crest forming most of the right vertical leg. The rest of the right side, the bottom, and the left side seemed to be formed out of cross country bushwhacking, road walking, and a few trails. It made no sense to me and I was planning on hiking the best of the Kettle, then cutting due west into Republic.

The road route was shady, but the warming air and the 4000 feet of elevation that I gained brought sweat out of my body quickly. I passed some lazy cows on the ascent, a few of which were so lazy as to not even bother to get up and run with the rest of the herd at my approach. My nice, big gravel road degenerated into a ATV/ORV track labeled with various numbers. Although the map and the guidebook indicated that there was a lot of water along this section of trail, actual experience proved otherwise.

The route was shady enough and it was cool enough at this higher elevation that this wasn't too much of a problem for me. Most of the sources were mud pools or scummy water or otherwise non-recoverable. If it had been blazing hot out, like yesterday, I would have been a pretty unhappy hiker. The roads in the area were being allowed to disappear by the US Forest service. In a few stretches someone had come through with a chainsaw to cut out deadfall, but most of the distance was passable only on foot.

My route turned to the south and climbed out of the forest to open hillsides providing extensive views into the distance. Unfortunately, many of these views were of clear cut hillsides. Nonetheless, I enjoyed these kinds of views, where you can see for a long way in every direction. Where there is a lot of open air around you with nothing to hem you in. Not mountains, not buildings, not interstates. Just space. Going for a stroll along the floor of Death Valley to see what I mean by this. Everything around you seems to amplify and bring out qualities that had remained hidden before.

The environment that I was in now, however, was not barren. It was lush and filled with life. But walking along the top of the crest through, most likely, and old clear cut, put me in the open air and the feeling was the same. This is different than being on a craggy alpine ridge with glaciers falling away beneath you and nothing but snow, ice, and rock all around you. There is no life there. Here, it is everywhere. The feeling is different.

I was no longer on anything that resembled a road and was quite pleased by the route that the PNT was taking through the region. Like many trails in the Smoky Mountains, my old stomping grounds when I lived in the Midwest, these roads had decayed into trails and now served hikers and local hunters, or anyone else who decided to come for a walk. Although it tempted me to do the full orbit around Republic, the few first hand accounts I had read of the hike south of SR20 did not sound appealing at all. Besides, I liked the idea of finding my own way down out of the mountains and into Republic. The fact that all I had were crappy, large scale Delorme maps didn't bother me very much, probably because I tried not to think about it a whole lot. The trail/road dropped me down to a trailhead parking lot and camping area and I lost the true way. But, I walked to the end of the camping area, hopped a fence and dropped down a steep slope to SR20 and the start of the Kettle Crest trail.

It was early in the day, but I was almost done hiking. Because of water, I could either hike for another couple of miles and call it quits at a creek at just about the 20 mile mark, or hike for another 10 past that to get to the next spring. However, if I did that then I would have private property issues on the hike down to Republic. Hence, I sat and enjoyed a good long rest, watching a few cars drive over SR20, but mostly I just did nothing. One of things I did managed to do was take my hiking poles off my pack, extend them, and get them ready for use. Since coming off of Two Mouth Pass I had been entirely on roads, active or abandoned, and there is no need to use poles on such things. I sat for a good forty minutes before picking myself up and heading up the gentle trail. Given that Mount Henry had a National Recreation Trail to the top of it, there was no guarantee that the Kettle Crest would be any good. But, it was clear, from the very start, that it was lovingly maintained by local hikers, riders, and cyclists.

Good tread. A rare thing out here on the PNT. In fact, I hadn't had a long stretch of quality trail since leaving Glacier National Park. Either the maintenance had ended quickly or never existed. But here on the Kettle Crest I had a nice, long path in front of me free of blowdowns, burned areas, overgrowth, or other signs that nature was taking back the trail. I climbed through the forest and emerged onto open slopes where the views to the west immediately reminded me of southern California on the PCT. Desert mountains and hills rolled forward for as far as the eye could see. It was hot, dry, and brown where I was heading tomorrow. I was nearing the Cascades, but before I could get there I had to cross a large volcanic plain and drop all the way down to the Okonogan River before I could climb back up. It would be a roaster, for sure.

The trail climbed gently through open slopes with flowers strewn throughout. The Kettle Crest was my last chance before the desert began to enjoy the luxury of things like shade and green-ness. I found some shade to sit under and rest for a while, not because I was tired but because I knew that it wasn't much farther to my creek and hence my home for the night. The last few days had been a bit trying on me due to focusing so hard on reaching Oroville, the symbolic half way point of my journey. After Oroville I'd be in my home range and because of this I'd been obsessing over it to the point of not being able to enjoy what was around me. This changed dramatically once I started up the Kettle.

I hiked for another thirty minutes, descending down into a draw where I found the promised creek, but not the campsite I had hoped for. I wandered through the brush looking for a camp, but ended up having to back track for two minutes to an open, grassy slope where I could bed down. A flattened spot in the grass indicated that others had found it quite acceptable as well. Within five minutes I had my tarp up and my bed for the night made.

It was only 4:30 in the afternoon, so I took the opportunity to make a pot of tea before dinner and enjoy some light reading. Xenphon, The Anabasis. Books written by old Greek men can frequently be boring, dull, and completely confusing to readers due to the, for us, strange cultural and religious traditions of the Greeks. But Xenophon is different. The Anabasis is an adventure story of a Greek mercenary army trying to fight its way out of Persia and get back home. There isn't anything strange or awkward about it. I had read it a decade earlier and, due to the nature of the trip, I thought it would be perfect for my long walk this summer. Indeed, it was.

I spent an idyllic hour sitting against a tree reading Xenophon and drinking tea, the grass gently waving around me. Days like today were not hard to enjoy. While it was true that none of the scenery today could be remotely described as breath taking, such was not the purpose of being out here. If i wanted perfect scenery, I could go to the Spectrum Range, or the Khumbu Himal, or the Glacier Peak Wilderness. Or any number of places. No, today was easy to enjoy because the views were comforting and interesting, combining distance with desert and green. The route had been a good one that was easy to follow. It was not too not, nor was it too cold. And here I sat with nothing better to do than read a classic adventure story written thousands of years ago drinking tea grown on the other side of the world by people who, had they read Xenophon, would have understood it just as well as I did. I was happy here, content here. Having just what you needed, and not wanting anything you did not need, that was happiness. That was contentment. The hard part was knowing what what you needed and what you did not.

A light flashed across me. Voices. Heavy thumps. Within a second or two I was up in the blackness and listening and looking to figure out what it was that had woken me up so quickly. I sniffed the air. I waited. And then I heard it again. Two horses thumped the ground. Two riders with headlamps were coming down the trail at 3 am. I heard them go by and then went back to sleep after putting on my down jacket for a bit of additional warmth. When I emerged from my tarp it was still cold, but the sun was shining and that made everything cheery. I was looking forward to the day immensely, glad to be alive and eager to see what would happen with the day I'd been given to live. I drank my tea and ate two Oatmeal Squares for breakfast while looking over the route along the crest. Profanity Peak sounded entertaining. I packed up and sauntered down the trail. I hadn't gone more than a minute or two beyond the creek when the itch in my mind started.

The itch was a memory from five years ago and started with a simple image. I was standing at a bus stop in Seattle with Birdie, waiting for the bus to the airport where I would catch a flight back to Chicago and, eventually, return to settled life in Bloomington. It was a day that I had been actively loathing for many weeks now and passively since May. We had finished the PCT together a few days earlier, then a day at Manning Park and another in Vancouver. Yesterday we had ridden down on the Greyhound to Seattle and gotten a room at the fabulous Commodore Hotel near Pike Place Market. It had cost less for the two of us there than it would have to get two bunks at the Green Tortoise hostel down the way. This was the itch. I had been filled with the remembrance of that moment when the bus came around the corner and I said goodbye to Birdie and watched her walk down the street, leaving me alone. More alone, and lonelier, than I had been all summer long, even in the midst of the empty places of the PCT when I had no one around. But I had all of the world. I had the PCT. I had my time and my summer. But at the moment she left, I was empty inside. It would take time to understand all this.

But the itch had started with that memory. The scent of her hair and the feel of her body from our last embrace lingered with me even here. And so I began to remember in an attempt to scratch that itch. The Green Tortoise. The cost of the Commodore. Buying beer at Pike Brewing and eating spectacular nectarines and peaches at the market. The All You Can sushi and Korean barbeque joint where we had feasted in Vancouver. But there is no sense in remembering if you don't remember everything, so I went back to the very start of it all. The start of that summer of transition. It was foundational in my life. And still is.

I hadn't even noticed the climb to Profanity Pass. Wildflowers bloomed and sage came out for the first time on the trip. Entire hillsides were covered in sage, perfuming the air with a pungency that carved a hole in my nose and injected itself directly into my skull. I grabbed a handful off of a bush, smashed it roughly between my hands, and stuck my nose directly into it. I breathed deeply and the scent brought out more memories. Southern California was filled with sage. Indeed, sage is the scent of the PCT until you near the south side of Mount Hood and you begin to enter the rainforests of Washington.

I remember precisely sitting in my car camping chair in my empty apartment with only a few clothes, my pack, and my digital alarm clock writing in my journal and drinking a cold beer. Tomorrow was the day I would leave for Chicago and the day after that I'd be in San Diego. I had gone down the street to a student bar and bought a gyro and a cheeseburger in a vain attempt to put on a little fat before what I thought would be an arduous grind. I sat and wrote in that green fabric chair and today I was remembering it as if I was doing it right now, at this moment.

The scenery around me was spectacular. Open and rolling, with rounded mountains stretching on along a seemingly endless ridge. Down in the valley it was hot and brown with signs of a scattered habitation. I walked along and smelled the sage and enjoyed the feeling of the cool air blowing over my arms, stretched out like a child does when they play at being an airplane. The trail switched sides of the ridge giving me a new view, the same in beauty, differing only in petty details. I was caught somewhere between today and five years ago, caught between today and yesterday. The edge of time was blurred and its precise boundary lost to me. I knew where I was and what I was doing and what day it was, but the part of my mind that actually mattered was adrift in time. This had happened to me before and it had ceased to frighten me.

I remembered every campsite along the PCT. The powerful smell of honey that came off of Glory's hair every time she brushed it, even if we had been out of town for more than a week, pulling 30s and sweating hard. The cold feeling of the wood floor on my bare feet in the Ashland hostel. I went through every single day of that summer in my head. The memories were powerful and vivid, even down to the smell of the Irish wolfhounds in the SUV that had given Sharon, Will, and I a ride into Chester for breakfast. The bacon wrapped meat loaf that I ate in the Pancake House at Snoqualmie Pass, watching the rain fall on a Greyhound bus stopped outside, picking up passengers for the run into Seattle. I could go there, I thought then. Instead I bought some beer and supplies and sat in the empty motel room watching television. And then how happy I was when Sharon arrived unexpectedly, having put in a 40+ mile day to reach the pass after finding a taunting note from me that I had left near Stampeded Pass in a five gallon paint bucket filled with Snickers Bars, beer, and other goodies, courtesy of a hiker named Dewey who lived in Seattle who said, "I understand how you feel at this point.".

I had walked past a nice, fenced in spring and arrived a mile or so later at the very muddy, but quite serviceable Midnight Spring. Cows and cow dung were everywhere and the trough didn't look very appealing, but the actual spring was fenced and I was able to re-direct the pipe into my water bag. I didn't bother to treat the water, which was sweet and pure, direct from the ground to my belly. I continued loping along, looking for a place to take a lunch break in the sun, for it was quite pleasant out at this elevation.

The area had burned a while back, long enough ago for shrubs and small plants to gain a foot hold in the soil while the trees were still small and hadn't swallowed the sunshine completely. Shortly after setting out, I reached a trail junction and the base of Copper Butte, which was my next destination. I sat in the dust and looked around me, glad that there was no one here for me to talk to about my summer or about where I was heading. I wanted to remember while walking along one of the most beautiful ridges I had ever been on. There would be time for other people on other days, at other times, in other places. Jason and Joe and John could wait for a while.

I sweated on the climb up Copper Butte, but the cool breeze on the open top refreshed me almost as much as the expansive views did. The display of wildflowers was immense, with purple lupines dominating the landscape like Rainier does in the Puget Sound area. Most of the year lupines have very little scent, but for a few weeks every year they explode in a perfume finer than anything Paris has managed to cook up. And they were everywhere on top, giving the ridge an aroma unique to the flower.

I strolled slowly along the open top admiring what I could see, but my mind was far away both in space and time, remembering to what I was before I went out on the PCT. I saw what was in front of me and smelled the air around me and felt the cool breeze on my sweaty skin, but I was also seeing and smelling and feeling things that had happened six, seven, a dozen years ago. I passed the foundational remains of an old fire lookout and my thoughts were briefly interrupted by the notion that this would have been an excellent, if windy, campsite for the night.

I picked through what I had done while in graduate school at the University of Illinois, year by year, tracing my development as a student of mathematics, as a person, and as a human being. The memories were especially vivid and seemed to come out of nowhere, for there was no reason to remember back to 1998 when I sat in Ar-Ri-Rang with my friend Rich, eating Bi-bim-bab in the early evening one cold and rainy November day after a hard day of mathematics, listening to two business students argue about the wisdom of replacing the dollar with shares in corporations. Why in the world had my brain remembered that? And why was it so vivid in my head now?

I descended off Copper Butte through the woods and continued to scratch the itch that had started many hours before and many miles earlier. The memories continued to be intense and they were beginning to drain me of strength. The mind is strong like that: Mental exertions can overwhelm the body completely. But I kept on remembering. Four weeks spent at Penn State in the summer of 1999. I had gone on my first day hikes that summer since being a Boy Scout. Everything started then. October of 1999 and a 45 mile hike along Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore in the upper peninsula of Michigan. The colors, the fear, the seemingly endless danger and tall physical challenge it presented to me then.

The trail dropped down and ran along a low part of the ridge before beginning to climb through the woods and back to the open lands of Wapoloosie Mountain. I was tiring. Fading. The open top cheered me, but there was no denying that I was starting to fall apart physically under the weight of the memories. I moved off the trail and sat in a patch of lupines the stuck up over the tall grass. Pack off, I laid on my back and looked up at the sky in the flower patch and rested. A couple of hikers were crawling there way up another trail toward me, but would not reach me for some time. I closed my eyes and relaxed in the grass and the lupines, breathing deeply to capture as much of the fragrant air as I could.

I wasn't sure if I had slept or not, but I felt better when I opened my eyes and put my pack back on. It was unlikely that I had been asleep for long, for the other hikers surely would have woken me up when the passed by. The open top of Wapaloosie was simply fantastic, extending for a half mile or so. Flowers, views, and easy hiking were making the Kettle Crest the best section so far of the PNT.

The open views gave me a sign of where I was heading in the near future. Although I couldn't see the highway, I could see Sherman Pass through which it had to run, along with the last few humps on the ridge that I had to climb over to get to the pass and my route into Republic. What exactly that route was I didn't know yet, but something would surely come up.

I began the descent, steely at times, to the notch from which I'd have to climb up to the top of Jungle Hill. I passed several fine campsites and springs, each tempting me to stay the night and get some rest. I was still tired and felt like I was running on fumes. The route took longer than I expected and the mileage numbers in the guidebook didn't match up with the mileage on the ground, which was something I had gotten used to this summer. I reached a trail junction in a bit of a funk and made a snap decision to follow a different trail. It headed in the right direction, though I wasn't exactly sure where it would end up. It did have a name and the trail bed looked good. I had had enough of the ridge line and happily began my detour off the Kettle Crest.

The trail dropped me down for a mile or so on excellent, well maintained trail, but then it just sort of died out in a flurry of cattle trails. I wasn't exactly lost, but I ended up milling about for a while looking for a sign. I wandered through the woods following cattle trails in the direction I thought I should go and joped for the best. Eventually I spotted a bit of pipe sticking out of the ground. At some point it probably helped a stream flow under a trail, but I could see neither stream nor trail. But, a human had put it there, which meant I was going in the right direction. A few minutes further and I was back on solid trail, which I followed down to a trail head that sported a herd of cows and no sign that a car had been there in some time.

Although the cows complained loudly, I shooed them away and walked through the scattering herd and down the road. The four foot tall plants growing out of the middle of it was a sure sign that it didn't see a lot of traffic in the summer time. Occasionally I'd startle a cow and calf standing a few feet off the trail in the woods. I could tell the age of the cows by their reaction. The older ones just stared at me and chewed. The younger ones and the calves raced off bellowing in terror. I continued down the grassy, probably abandoned road for about a mile. It improved to gravel and soon thereafter I found a huge, open campsite set back from the woods with a stunning view of the valley below me, the valley holding the San Poil River and Republic. A strong creek came running down from the hillside above me. Perfect. Even though it was only a little after 5 pm, I had covered nearly 25 miles today and the memories had tired me out. I dropped my pack and set up camp while water boiled for the evening meal of broccoli and cheddar rice.

After finished the pot of preservative laden food (it tasted so good!) I leaned against a tree and tried not to think for a while about anything more pressing that what I would do tomorrow. Republic was close, though I didn't know exactly how I'd get to it since I the large scale Delorme map didn't show many of the roads in the area. But, I had a direction to go and just needed to avoid upsetting anyone by trespassing on their land. Once I crossed the Cascades I wouldn't be able to easily get a motel room any longer due to tourists and prices. I wanted to save money for a hotel room in Anacortes, after I had finished the long crossing and hiked through part of Puget Sound. It would be pricey, but worth it. Still, I wanted to take a shower and sit on something soft and eat town food and drink beer and learn about Republic and the people that lived in it. I had really enjoyed all my other town stops and the thought of blazing through Republic was repulsive to me. I knew what the backcountry was like. I knew what wildness was like. What I didn't know was what Republic was like. Tomorrow, I'd get to find out.

It was another cold night and hence a slow start in the morning. I wasn't exactly sure how I was going to get to Republic, but the gravel road had to lead somewhere. I hiked down the road for about twenty minutes until it T-eed into a nice paved road without a sign on it. I scratched my head for a moment and decided to go to the left, but there was no particularly good reason for doing this. Another forty minutes got me to a set of power lines running downhill, with a rocky track along side them providing what looked like a route down to Republic.

I checked the map and found that the power lines were on it and did run into town, more or less. I didn't especially like the look of the road, but figured that I could just follow the lines if the road went elsewhere. I left the paved road, which I suspected would dump me out onto SR20, for the rocky, rutted, ATV only road. It followed alongside the power lines for a while, then moved a little ways off for a bit to avoid, as I found out, some private property.

The first thing I saw was the car. Old, junky, stripped. Up the "drive way" were some more cars, also quite stripped. And a toilet. No barking, snarling dog came charging out to challenge me, which I took as a sign that there was no one around and so no one would care if I went up and had a look. The drive way led up to a clearing filled with yet more stripped cars, appliances (including the mandatory refrigerator shot up by pistols, rifles, and shotguns), and other remnants of a life once lived. A cabin sat off to the side of the clearing near the power lines. The door was closed and all the windows had glass in them, which seemed to mean that someone did live here from time to time. I wandered around a bit more, then started to get a bit frightened, though I couldn't quite put my finger on what was spooking me. I left quickly.

Another twenty minutes got me to a good, gravel road, also unmarked, which I took a left on and soon passed yet more stripped cars. I was getting more and more frightened, though I still couldn't figure out why. As far as I could tell, I was the only person out here and there is little in the natural world to be scared of, short of grizzly bears, sharks, and Mormons. I took a right on a large, gravel road, and this turned out to be the right way. I soon dropped down to the west along a shady lane without cars. The feeling of fear left me at about the same time that the road flattened out, lost its shade, and began to pass along working farms. It seemed that the farms were devoted to growing hay and not much else.

The day was heating up quickly, especially given the relatively low elevation of Republic and the Sanpoil valley. I turned the radio on and found an insipid country station to listen to. Everything else was static. I actually really like country music, just not the majority of what passes for the genre these days. Like the blues, country music is a cultural expression of America and reflects the experiences and lives of a large portion of the populace beyond the urban centers. Listening to a Johnny Cash song, or something by Hank Williams, George Jones, Willie Nelson, or Waylon Jennings, or a lot of others, you hear a part of Americana that, unfortunately, is fading into the past just like Metaline Falls. How many people still remember Woody Guthrie or the America he sang about? On the radio Jessica Simpson was singing about her love with a fake sounding plaintive wail, accompanied by the requisite steel guitar.

I reached SR21 and was soaked in sweat and getting a bit sun addled. Cars raced by in a hurry to get somewhere, to do something, to meet someone. It probably just looked like they were in a hurry. After all, I had been on foot living a very slow paced life for the last three and a half weeks. There was a road side diner which looked appealing, except for the masses of shiny automobiles and gleaming chrome motorcycles in the parking lot. Tourists out for a drive were not really who I wanted to spend time hanging out with. I walked down the road and about eighty minutes later I entered the outskirts of Republic.

The town itself was, it seemed, quite alive and thriving. Unlike Metaline Falls, or Northport, or even parts of Bonners Ferry, Republic looked like a town that had something of a future. The high school, for example. Aside from the simple fact that there were enough children in town to support a high school, it looked new and well cared for, with a fine looking football stadium and track.

There were businesses and homes with gardens and other signs that there was actual life in Republic. But it was so scorchingly hot out that I didn't linger long and plodded on into the central part of town. Republic sat at an intersection, with SR20 running east-west and SR21 running north-south. A lot of people would have to pass through Republic, but the town seemed to be more than a simple stop off the highway on the way to somewhere else.

I emerged onto Main Street, sweating hard and glad to be nearing the end of my day. I couldn't imagine pushing on in this heat, along a blacktop road, and hoped that I'd be able to find some place cheap to spend the night. There was a city park of sorts where I could camp as a last resort, and next to that was city hall, complete with a mural on its side that told some of the story of the founding of the town of Republic.

The streets were wide and clean and there wasn't a single empty business. I hadn't seen any signs of industry on my walk in and couldn't quite figure out where the money was coming from. There was no sign of the cancer that was eating away at Northport and Metaline Falls here and I was interested to find out how Republic was thriving here in the middle of nowhere.

I walked past the city hall and noted the no camping sign in the park, though it didn't look like it would be hard to get out of sight of the law. Down the street I passed a couple of hotels, bars, and cafes, each of which looked inviting, though for different reasons. Both hotels looked to be a bit on the spendy side, so I continued to the far end of town, two blocks away, and found the Klondike, which looked about right. Well cared for, modest, and without too many cars in the parking lot it seemed like the most obvious choice for a place to stay. A friendly black dog came out and smiled at me as I walked up the outside stairs to the office. I patted it on its head and it followed me to the top, where it proceeded to lay in the direct sun and go to sleep.

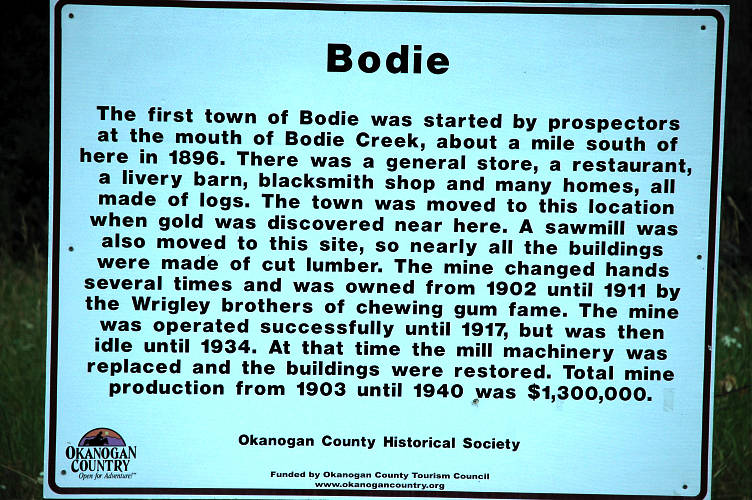

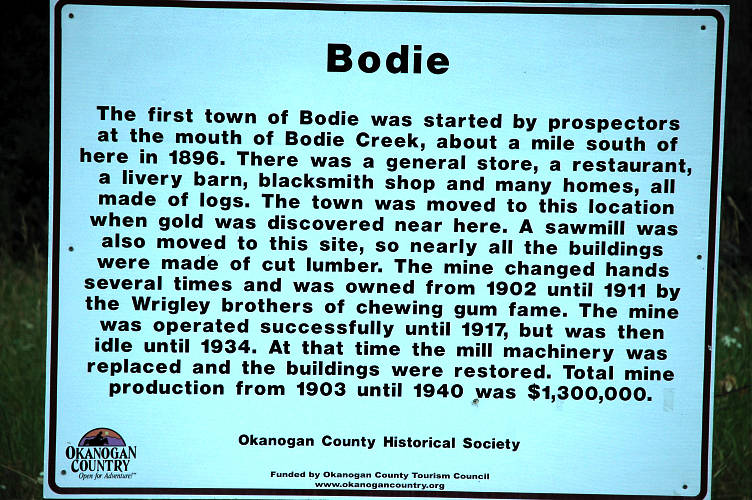

There was no one in the office, so I set my pack down and had a seat in a swinging chair in the shade next to the office. Now that I was in town, I had nothing much to do and could afford to sit here and rest for quite some time. The dog, apparently an old one, would occasionally get up and stretch, then go back to sleep in the sun. After forty minutes a middle aged man came out, saw me, and went to find his wife, who ran the business. They were all full up for the night, she said. I looked around at the half empty parking lot and couldn't believe it! Thinking that she might mistake me for a vagrant, which I was, I told her about my trip so far, where I was heading, and how long it had been since I had slept inside on a bed and taken a shower. She warmed right up to me, but still insisted that all the rooms were reserved for the night. Miners, you see, had booked up all the rooms. So that was it. That was the reason Republic wasn't decaying.

Republic had been founded, like so many other places I had been to this summer, to exploit the natural resources of the area. The town was well situated near the Kettle and Sanpoil rivers, which provided power, transportation, and irrigation for the people who lived there and dug things out of the ground. IN the last decade the boost in prices for raw materials had brought active mining back to Republic. Like logging towns, I wasn't sure how I felt about mining and its impact on the environment. I wasn't naive enough to believe that we could live in a world without mines, or arrogant enough to condemn it as evil. I wasn't an engineer and didn't know what impact the mining was taking on the surrounding environment. The best I could do was hope. Republic was, after all, a healthy town.

The woman and I talked for twenty minutes or so and then she got on the phone and started making phone calls. The Northern, the fancy hotel I had passed on the way in, had a room for the night, but it would cost me. $71 a night isn't cheap at all and was about $40 more than I had thought I would have to pay. Still, this is why I have a job during most of the year, I thought. I walked back down the street and had a delicious calzone and huge plate of salad at the Tamarack. Although I was a bit early in the day, they found me a clean room and let me check in. I drew a lot of stares from the various teen-age cleaning girls, whom I suspect were just curious about who this bearded, backpack carrying, dirty man was who was checking into the hotel.

I dropped my pack inside, cranked up the air conditioning, and walked across the street through the blistering early afternoon heat to the super market, where I scored several cans of strong beer and the sunday edition of the Spokane Spokesman Review. I hustled back to the hotel with my bag of goodies, stopping only long enough to talk to one of the braver cleaning girls who stopped me in the parking lot to find out my story. This, of course, delayed the shower and air conditioning that I was looking forward to, but talking to a pretty girl is never a waste of time. I gave her the short version of the story to pass along to the other girls and stepped into a paradise of cold air, cold beer, and a hot shower.

I occupied myself for the rest of the day doing all those things that I can't do in the outdoors. I drank beer and washed clothes and watched television and laid on the soft sofa casually reading the newspaper. The flickering box in front of me confirmed what I already knew. We were in the middle of a heat wave and more was coming. In the early evening I went to a saloon next to the grocery store and feasted on a bacon double cheeseburger with tater tots, washed down with several pints of good microbrew. There were only a few drunks in the bar and the bartender was kept busy by them, which meant I didn't get any good stories about Republic. I picked up some ice cream on the way back to the Northern and spent the rest of the evening drinking even more beer and trying to expand my waistline as much as possible. This is what town stops are for. Towns are about luxury and indulgence and profligate spending. How I, or anyone else for that matter, manages to survive living in one most of the time is beyond me.

It was in the 90s when I hiked out of Republic after downing a fat omelet special and sending out an email update to friends and family. Why I thought it was a good idea to start hiking at 11 am, instead of hanging out until 4 pm or leaving at 6 am, was beyond me. I wasn't sure how long it was going to take me to make it to Oroville because I wasn't following the PNT there and could only guess the distance based on the Delorme maps. I was wearing shorts for the first time on the trip in anticipation of the heat and the sun on the road route that I was taking to Oroville.

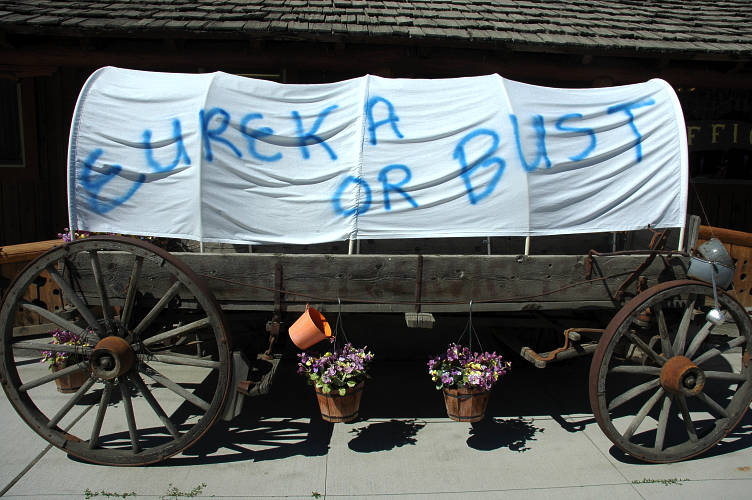

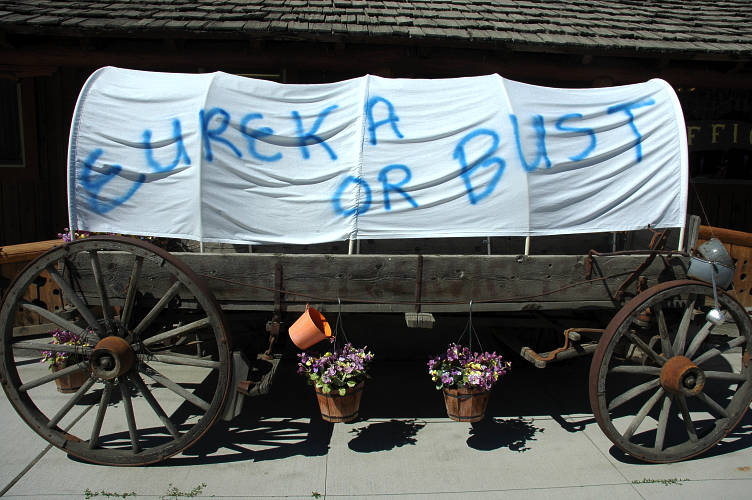

I hiked north out of town on Swamp Creek road, passing farms and ranches and a few residential homes along the way. Not all of the homes seemed particularly welcoming.

I was good and lathered when I reached West Fork Trout Creek road, which was going to take me Horseshoe Mountain and down to the Toroda Valley on the other side. Rather than go over Mount Bonaparte to get to Oroville, I would take a road route through some small towns. Although it would probably be less scenic, it looked short and the route followed water courses the whole way. Given the heat so far, this seemed like a wise choice.

The road climbed and passed a few farms with people actually working them. They didn't seem surprised to see someone coming through on foot and smiled at me when I waved at them. The country music blaring in my ear soon grew tiresome and I switched off the radio to focus more on my suffering as I ascended. One of the problems with making things up as you go is that you never quite know for sure if you're going in the right direction: You don't have the right maps. Where the Delorme map showed only a couple of roads, spurs branched off from my road many times and on several occasions I took the wrong one. I knew that I was on the wrong road when I would come to a barrier and a "Keep Out" sign indicating logging operations ahead. Then I would have to re-gain a few hundred feet of elevation and return to the main road. I was hot and sweaty and very tired when I finally topped out an estimated 5000 feet above Republic.

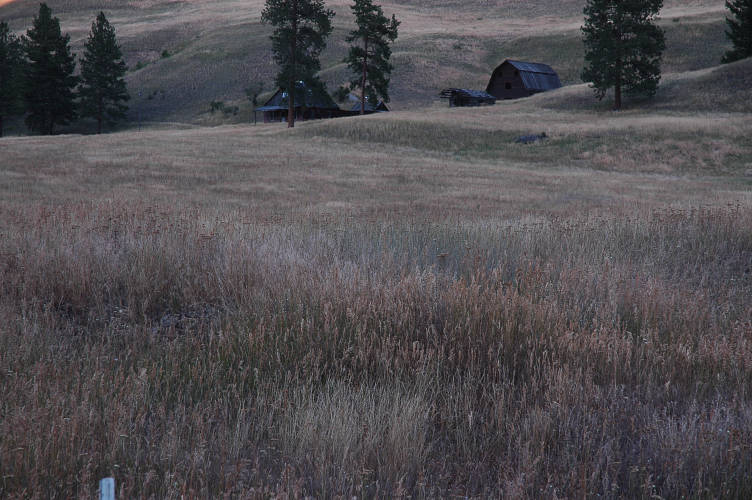

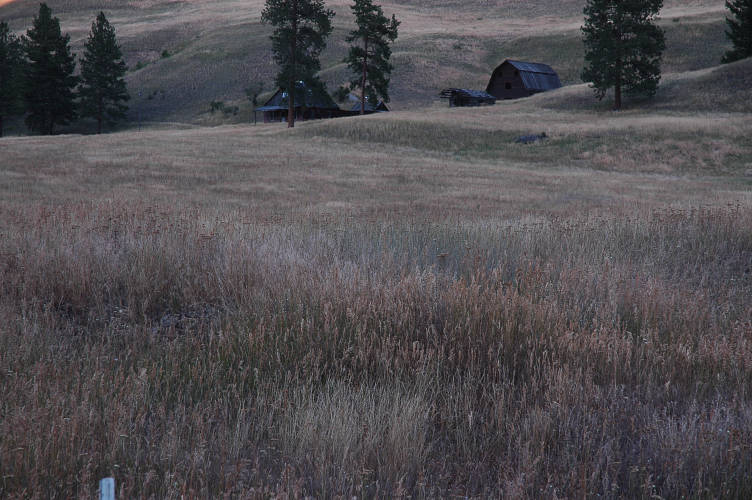

I wasn't quite sure I was on the right road when it began to descend steeply into a valley, but scars from ATVs indicated that someone had driven here recently, which was a good sign. I spied a run down shack in the middle of clear cut and knew I was on the right track: People don't live on roads that go nowhere. I passed a few more abandoned cabins and took a break in the shade next to a flowing creek where I could slake my rather substantial thirst. It was spooky down here. Every quarter mile or so I'd encounter a cabin with no resident, but with No Trespassing signs posted.

I was far, far from anything resembling society, which meant there was effectively no law out here except for what people agreed to. Its rare that I get spooked in the outdoors, but around other people without the protection of society it is easy to be afraid. I had no basis in experience for this fear. Rather, it is something that society has taught me. How's that for circular reasoning?

As I dropped lower and lower into the valley there were more houses to look at and to be afraid of. The standard array of stripped cars dotted lots, along with large buses, tires, barrels, planks, toilets, washing machines, kitchen appliances, and even a 1980s vintage microwave, which I found sitting on the side of the road. I would have paid $5 to know the history of some of the lots that I passed. Who lived there? Why did they leave? Where are they now? Why did they come here in the first place?

At some point it must have been popular to live up here in the middle of nowhere. One place I passed had a brightly painted bus that looked like it would have fit in at Woodstock or on Haight-Ashbury. There had been a Back to the Land movement in the area, but I didn't know much about it and didn't know who to talk to in order to find out. I upped my bid to $9, the price of an expensive movie. I thought this was a pretty good bargain, but there was no one around to collect it. To be around so many signs of human settlement, but without the humans, is rather scary.

I hiked down the rapidly deteriorating road and hit an intersection with a larger, also dusty, non-gravel road whose main users seemed to be a herd of cows. Of course, they scattered when I approached, lowing and bellowing as they went. Cows are funny creatures, which maybe isn't a surprise considering we've been breeding them for maximal stupidity and docility for many generations now.

I made a right on the road and continued past a few more abandoned homes. The road abruptly turned to gravel and almost instantly the properties became nice, the grounds cared for, and the homes lived in. It was as if I had just left the forbidden zone where nice people do not go, for almost immediately I began to see trucks again. A man on a Polaris slowly rolled down a drive way and struck up a conversation. I told him where I had come from and how I come come to be where I was. He hunted in the mountains and knew the confusion of roads I had just come through, but couldn't illuminate me on the history of the abandoned homes I had found.

I continued down the gravel road to Old Toroda road, which was nicely paved and on which a few cars sped by. I hobo-ed up next to a creek by the side of the road and cooked dinner over my beer can stove, feeling for all the world like a vagrant and not like a hiker. I loved it, even my smelly feet and beat shoes. I looked over my map to try to find a suitable place to camp ahead. Hmmm...Beaver Lake, creek flowing out of it, probably public land. I'd go for it! I polished off a potful of Idahoan Loaded Baked mashed potatoes and hit the road again, this time with the Spokane Indians baseball game playing in my ear. I was getting to know the announcer and the players, their statistics, and the various personalities of the league. The sun was setting pleasantly over the valley, giving a nice pink glow to the farms in the area. Rarely a car passed. Two tractors passed me along the way.

My walk this summer had turned into a full on vagrancy. The PNT travelled back country roads, but not the ones that I was one. I wasn't on public land and I didn't know where I would sleep tonight. And I didn't care. The feeling of freedom from material positions and responsibilities was palpable walking down that road. I had been feeling it all summer: Without the burdens of the rituals of everyday life in settled society I had no tethers to retrain me, other than my own conscience. It wasn't that I was ignoring responsibilities that I had taken on and was acting in a juvenile way. I had very deliberately relieved myself of the normal things that people do to fill up time so that they don't have to live their lives. Of course, they would probably say the same thing about me.

They would say, for example, that I was deliberately avoiding doing those things that make life worth living. I was doing so, they might assert, because I was afraid that I might fail at them or that I would become dependent on another person. Rather than accept the responsibilities that come with being an adult, they might say, I instead had decided to live like a little kid would, without thought for the future, without thought for the coming winter, without thought to when I was old and decrepit and sick and bed ridden. Of course, I think otherwise. I know that I will grow old, get sick, and die. There is no escaping this. At some point I will no longer be able to do what I am doing this summer and the time for it will have passed, never to come again in my lifetime. I accept this and it does not bother me to know that one day I will not be able to.

I reached the creek draining Beaver Lake and found someone's farm there, complete with barking dogs. I continued down the road in the increasing darkness to Beaver Lake, which turned out to be a swamp. It was now quite dark and I was mostly out of water, which was something of a problem. I spied a pull out, but there was a deer carcass there, which seemed like a bad omen to me, not that I believe in fairy tales or signs. I continued down the road in darkness, not sure where I was going to find a place to sleep. The road narrowed into a canyon and the land was constrained by the swamp on the left and a few homes on the right, pushed up right to the road by the walls of the canyon. I walked along the road in the black night, breathing the cool air and watching the stars dance overhead, and I was not afraid.

It was brutally cold as I shuffled down the deserted road toward Lake Beth. I had spent the night in a little cave formed by other animals in a dense patch of vegetation. I had stumbled upon it in the dark while looking for a spot to bed down and was thankful to have found it. I was on someone's land, someone other than the public, and made sure I was gone early in the morning, not that anyone could see me in the cave.

The lake and the corresponding National Forest campground was not far from where I had camped for the night and I stopped in to pick up water and make tea to warm up with. I must have climbed quite a bit higher than I thought for the air to be this cold. But the sun was coming for me and the day was going to be a hot one. Two old men floated in a beat old boat, fishing lines in the water, Otherwise it was quiet. I sat and reflected about how far I had come so far this summer. Although today I would near 500 miles, physical distance was not the measuring stick I was thinking of. I drank my tea in the peace of the early morning and was thankful for what I had and where I was and the opportunities that I was blessed to have.

The road climbed through the narrowing canyon up to a broad, open plateau, where once again cars and trucks began to pass me. People, construction workers it seemed, were on their way to work. The air was still cool, but the sun was out in force on the plateau and I began to fear the coming afternoon. The land around me had been burnt gold and tawny by the sun, with the only green patches coming from the irrigated fields of the farms that dotted the hillsides.

After a restful break under the cover of some trees in a ditch by the side of the road, I continued tramping down the down and entered the hamlet of Chesaw, which looked like it had seen better days. There was, however, a fine store and a robust rodeo arena. One car passed me and I saw no inhabitants on my way through town. The road climbed and climbed, working hard to get over a ridge of mountains to the top of another plateau. Mary Ann Creek was flowing hard, giving me hope for later in the day when I would need water. My plan had me crossing a very dry looking plateau and then dropping into Oroville along Tonasket Creek, which looked like it drained a very large section of land, including the PNT route. It would have to be flowing. It had to be, because otherwise I would be in a bit of trouble.

The top of the plateau proved to be very scenic, but also blisteringly hot. I walked along, passing a few farms and other habitations, but I had the road mostly to myself. A few trucks stopped to see if I was ok or if I wanted a lift. I talked to one old man and his wife for ten minutes in the middle of road. Not a single other vehicle passed. It was nice to think that I was being looked after, even though I was a stranger in the community. This had been true, with very few exceptions, since I set out from Waterton and it was not something that I ever experienced in cities, in urban environments, in places where the cosmopolitan ethic is to ignore your neighbors and any strangers that might appear. They might be up to no good, after all. The reason isn't hard to understand. The sense of community is very strong in rural, relatively un-populated areas. In high density urban centers the sense of community is destroyed by the anonymity of the crowd. Without a sense of community, there is no reason to care. It is someone else's problem.

I stopped under a shady tree and drank the last of my water, all 1.5 liters of it. Although it is reassuring to have some water with you, it is better to have it inside of you where it can do some good. I napped for a little while and then set out once again, though this time with a clear NPR signal ringing in my ear. There was a memorial to Alexandr Solzhenistyn that completely misunderstood the man and his work. The fools at NPR (the first time I had ever used those two words together) couldn't understand why he railed against the Soviet Union and its lack of freedom and then, when he was expelled from the USSR and emigrated to the US, why he railed against America and its materialist, consumerist ideals. They even went so far as to assert that he was ungrateful to the US when the Soviet Union fell and he moved back to Russia. But all was forgotten when I rounded a farm and came through to a clear view of the mountains in the distance. The Pasayten. The eastern edge of the Cascades. On the other side was the Sound and home.

At this point I had been walking for two hours since my last break and there had been no sign of water on the route so far, except for a few cattle troughs, from which I declined drink. Thirst was building rapidly in the hot air, which was getting only hotter as I began dropping off the plateau and toward Oroville. I estimated that I had another dozen miles to go to reach town, which was a solid five hours of travel time. I had to get water out of the Tonasket, which should start appearing soon.

Another hour passed without water. The Tonasket was bone dry. It was a major water course but had clearly dried up a month or more ago and I was stuck without water and without hope of finding a natural source. The only question was whether or not I would ask for help from a stranger. I continued descending the now busy road, and didn't even have a chance to ask for help: The canyon was narrow enough that there were no homes to ask for water at. Just a dry river and a canyon wall. Slowly I emerged from the canyon and into a broad valley that held homes. A few had sprinklers going on their emerald green lawns. I watched the water fly through the air with something that very closely approximated lust.

I could stand the thirst no more. I saw an old man tending a garden and walked down the drive way toward the house. A dog came racing out, barking and snarling, but I could see that this was no fighter. I smiled and clapped my hands and made soothing sounds and quickly was scratching its head and patting it on the ribs. It followed me to the house where a woman and her two kids met me. I explained my situation and she came out and fired up the garden hose for me, smiling all the while. The fact that I had charmed the dog probably helped, but I thought again back to the urban-rural divide that I had been thinking about for a large portion of that day. Of this summer. If some beat, homeless person had shown up on my doorstep in Lakewood and asked for water, what would I have done? Would I have filled up their water bottles? Or told them to go down to the creek. Or to get a job? I thanked the woman and continued down the road to Oroville, which the woman had told me was about four miles away.

The last mile almost broke me. Another few cars had stopped and asked me if I wanted a lift into town, but I kept on tramping. What almost broke me were the apple orchards. The route into town led past extensive orchards which they were irrigating at the time. Rather than a drip system, they sprayed water into the air in a fine mist, which sent the humidity in the area to 100% and which seemed to suffocate me. I passed a teen walked down the road with sagging pants and no shirt on. I realized after we had passed that he was afraid of me and had been trying hard not to show it. I walked into the residential part of town and felt eyes on me as I tried to locate the down town area. I didn't have a map capable of guiding me to the right spot and I didn't feel like asking at any of the houses. But, I managed to find the Okanagon river and from there found the apple loading areas. I strolled through concrete parking lots with weeds growing up through the cracks and apple crates sitting idly by, waiting for the fall harvest season to be of some use to someone. Finally I made the right guess and came out onto the main drag. And more men walking around without shirts. But more important than the shirtless men was the Camaray Motel, right in front of me. I could smell the scent of cheapness in it and wandered over, dropping my pack outside the business office so that I wouldn't be immediately identified as a vagrant.

The air conditioning was on full blast and I wore only a bath towel in the chill air of the motel room I had gotten for $40. A can of Hurricane Ice was cold in my hand and the cheap, strong beer hit me hard in the head. I had eaten a 2/3rds pound bacon cheeseburger in a diner around the corner before hitting the shower. And, I had run across some very shiftless looking men without shirts on. I was starting to feel a little self conscious as I was the only male under the age of sixty who seemed to wear a shirt when going about in public. Besides youths loitering around the gas stations and restaurants, I had also encountered several very young looking women who were also very, very pregnant. Oroville was definitely not like the other towns. Though definitely in the country, it seemed to have many of the problems of larger cities. The seasonal nature of work here could have something to do with that. So might the transient nature of the work force, who had to move from place to place where there was work in order to survive and to provide for their family. It was the community thing once again. Lakewood suffered from lack of community because of the military bases in the area and the short-term deployments that the military, especially in recent years, have been forcing on people. This was all to much to think about. I cracked another top on a can of Hurricane Ice and found a movie about commandos to watch while I sat on the soft bed in my bath towel. Like Zach once said, "What does the billboard say? Come and play, come and play,...".