Homecoming

Oroville, WA to Glacier, WA

August 8, 2008

It was frigid inside the massive Prince's Emporium supermarket cum lifestyle center. The place was sprawling, like a Sam's Club or Costco or football stadium and the air conditioning was cranked high enough to make an Inuit put on a parka. Today was a planned zero day, a day of doing nothing except resting and getting ready for the push through the mountains. I was trying something that people had warned me not to do: Make the resupply run across the Pasayten, around Ross Lake, through the North Cascades, and all the way to Glacier, WA, a distance of, maybe, 220 miles. I was planning on eight full days plus a partial day to make that distance, the furthest I'd ever gone without resupplying, to Glacier, which is little more than a small store and two restaurants. I could have put together a mail drop and arranged for someone to hold it at Ross Lake Resort, but that just didn't seem sporting to me.

My cart loaded with goodies, including some beer for later one, I went through the check out lines and then stumbled back to the Camaray through the intense heat of 11:30 and sought refuge inside of my air conditioned motel room. Earlier I had picked up my bounce bucket and a package of new shoes from the PO, which had the requisite shirtless man standing in line (he needed to get a money order to pay a court fine). I spent the afternoon drinking Hurricane Ice, purchased with $2 that Peter had sent along (48 ounces of 8.4% beer for $2 is quite the deal), and eating cookies that Kari-Ann had put into the shoe box for me. I even found time to do some work, like repackaging the food and sorting maps. It was going to be a blisteringly hot walk tomorrow, I thought. There were 25 miles of low elevation road walking to get to the start of the mountains and the relief brought by higher elevations. I even plotted out what looked like a better, more direct route into the Pasayten, one that used an actual trailhead instead of bushwhacking along "trails" that didn't show up on anyone's maps other than those in the PNT guidebook.

After calling my mother I went to the well appointed library and sent out another email update to friends and family and watched the smutty images that the thirteen year old boy next to me was downloading. Pretty brazen, considering the librarian was wandering around the library the whole time! And so my zer day passed like most others. I stuffed my face with a large quantity of pizza, downed more beers than was good for me, and luxuriated on the soft bed and air conditioning. Tomorrow all these luxuries would go away. I wasn't sad for their being gone, for if I had spent another day amongst them I would have come to start to think of them not as luxuries, but rather as shackles, albeit shackles with a velvet lining.

I stood on the street corner outside the Camaray with my heavy pack on my shoulders and shook my head. Not in disgust, but more in line with the sort of resigned despair that people who have an unpleasant task in front of them frequently have. The temperature at 7:30 in the morning was already 80 degrees, as reported by the local bank. It wasn't just going to be hot today. The Weather Channel was reporting that it had been 103 yesterday and was going to get up to 105 today. And I had a full pack with 9+ days of provisions in it and 3 liters of water, with a long, shadeless road walk in front of me. I tuned in NPR and started out on the already hot road. There was nothing else to do but start.

The Cascades, like the Sierra Nevada of California, form a major barrier to precipitation coming off of the Pacific and keep the eastern slopes from getting much precipitation. The land had been drying up since I crossed the Kettle Range, but here, at the foot of the mountains, the rain shadow was at its most extreme. Sage brush was the dominant species here and the road side was filled with the bush. As the day heated up, the plant released more and more of its odor, which served as a sort of deodorant for the trucks that raced by, belching diesel fumes. I also had distant views of the Cascades, which served more as a torment than a carrot, for I knew that up there it would be pleasant and cool, but that i wouldn't get there until tomorrow.

I was on the PNT at the moment, following an old railroad grade along the Similkameen River, which was taunting with its water. I could get it when I wanted it, but it would do nothing to cool me down unless I decided to swim up it to the Pasayten. Along the way I had to content myself with NPR and not much else. No one lived out here, it seemed, and there were only a few squatters in their RVs by the river.

Some day, I thought, I'd like to write a book about the underclass of the mobile culture that we have in America. You see, there is already a wel established group of people who live permanently on the road. The wealthy ones are the ones you notice in National Parks or on the road in their heavy, lumbering RVs that outsize my apartment and have satellite dishes on top. Those aren't the ones I want to write about. Rather, I mean the underclass, the underprivileged, of these people. The ones with antique camper shells on the backs of rusted out 1970s vintage pick up trucks who have to work occasionally to get money for gas and who stay by the sides of the road in ersatz campgrounds, just like the Joads used to.

It wasn't some sort of romantic notion about the freedom of life on the road that drove me to this desire. I had no illusions about the pain and misery and suffering that such people inevitably encountered. I didn't want to be them or to live like them or to imitate their ways. But there was an authenticity, a realism, about how their lives were led that was distinctly lacking in the plastic, mass marketed life of today. I was learning a lot about life on the road, though from a sort of pseudo-vagrant's perspective (what self respecting vagrant would spent $40 for a night in a motel?).

Even though I was going through the motions of being a vagrant, I wasn't one in any way, shape, or form. I looked like one from an outsiders perspective, but I had the advantages of my past and my present and my future. I had an education and a strong, healthy body that was free of the addictions and traumas that might burden other homeless wanderers. I had credit cards in my pack and a full bank account and could buy my way out of any problem that happened to come up. If I didn't, it was because I chose not to. I had the resources, and that was a major advantage. I also knew that in a few months I would be back at work with a secure job, benefits, and all the comforts of home. The future, at least the future that was a few months out, was not unknown and, in comparison with, say, Jason's or Joe's, was rosy and nice and pleasant. Jason would suffer until the day he died. Anything that I might call suffering would end when I chose it to.

Around noon I began to approach the settlement of Nighthawk, with its green, irrigated fields and a few trees and houses thrown in for good measure. My hopes for finding a side creek had not been fulfilled and I needed water badly after slogging along the shadeless road for thirteen miles. That meant the Similkameen, whose purity was on the suspect side. Aside from the obvious cow dung that would be in the water, there would be pesticides and herbicides and fertilizers and the other trappings of the chemical society in the water. Hopefully my filter would work. The Similkameen was exactly the reason I bought it in the first place.

I reached the bridge over the river and nimbly made my way around and over some barbed wire fencing designed to keep people away from the water. Probably punk kids like to swim here, I thought. The fencing must be for them, not for honest people like myself. The water did look tempting and I decided that I was on the side of the kids. I was too tired and sun addled to go for a swim, and my clothes and body were still clean and fresh from two days in Oroville to need another scrubbing. I filtered water and sat in the dust to eat a hobo lunch under the bridge. I caught myself looking around for places to sleep, not that I was going to bed down here so early in the day. Rather, I had taken to looking for safe sleeping places almost unconsciously during the summer's walk. Although the underside of the bridge would keep out the rain, I didn't like being in view of the houses across the street or in a place that would so obviously get visitors. I stayed under the bridge and hydrated for a good hour before going back in to the even hotter sunshine of the early afternoon.

The afternoon stretched on and it became clear early on that I had not brought enough water for the hot walk to Palmer Lake. I had plenty on my back, but that was the problem: The sun super heated it, making it not so pleasant to drink and I only did so out of medicinal concerns. Palmer Lake, which had thousands and thousands of gallons for me, was walled off by a tight string of vacation homes and No Trespassing signs. The Well To Do were once again cutting me off from something that I badly needed. It wasn't a plasma TV that they kept me from, or a new car, or a computer, but rather a cold drink of water. I passed a few private camps with "Guests Only" signs and kept going. I finally stopped in the shade by an apple orchard and drank my 100 degree water. As I sat there there must have been a shift change, and old cars, packed with workers with skin browner than mine started to roll by. They waved. Nearly every one of them waved and smiled at me. I reached the far side of Palmer Lake where there was a boat launch and thought it would have made for a fine stealth camp. At least, it would have had there not been several families picnicing and froliking in the water. I moved on as there was still a lot of day light left and the heat was beginning to break.

Beyond Palmer Lake I entered the Sinlahekin Valley and began to regret my decision to take water out of Palmer Lake. The valley was farmed for as far as the eye could see, which meant more polluted water for the evening. My Delorme map showed that Sinlahekin Creek flowed into Palmer Lake and that I would cross it in a mile or so. I pushed on, turning down a few rides from concerned locals who brightened up when I told them where I was going. Everyone loves the Pasayten.

I turned off the main road onto Toats Coulee Road and walked alongside cow pastures, full of cows, of course, and a few hay fields. The stink from the beasts was strong, even in the open air of the valley and I wasn't looking forward to the water that they would surely have polluted. I reached the bridge over the Sinlahekin and was, to be sure, crest fallen at its sight. Slow, puny, miserly. It was flowing, however, and I had little other choice unless I wanted to walk for another hour or so. I hopped the barbed wire fence and dropped down to the shade of the bridge to see how bad things really were.

The Sinlahekin was a few inches deep and stunk like a feed lot does. Cows were just upstream drinking and defecating and the fields would leach poison into the water for me to drink. Filters are made for this, I told myself. I set up the gravity filter and comforted myself by reflecting that I had no choice in the matter, that I had to have water and this was the only source for some distance. And so I sat and drank the stuff which, after the filter, tasted fine, even if it did have a bit of cow smell to it.

I spent an hour under the bride eating dinner and when I came back out to the road the air was markedly cooler than when I had gone down to it. The high mountain wall provided some shade from the sun and movement was once again comfortable. I began the climb up into the mountains, passing Chopaka Road, which was the official PNT route, in favor of my own route. Hopefully, if I don't get lost, Touts Coulee Road will run me straight into 14 Mile Campground and a direct route into the Pasayten. But for now I had some climbing to do on the gravel road.

Although the air was cool, I sweated heavily on the ascent of the road, especially as it was near the end of the day and my body was not as fresh as it had been at the start of the day in Oroville. But I wandered slowly up the road, listening to the Spokane Indians game. I was a bit horrified at the start by the low flow of Touts Creek, but I eventually came to a power generating dam on it and above that the flow was strong. My water issues were over for now. I climbed for about three miles and came upon an open area where a cabin clearly used to stand. There were a few private property signs about but not right here and given the amount of micro-trash and shotgun shells on the ground I figured this was public enough and could plead ignorance and need if anyone happened to come by.

The chimney was all that remained of the former cabin and it held many tags from local youths. Today wasn't a weekend, otherwise I might be worried about nighttime visitors. instead of worrying, I sat and wrote in my journals and ate raspberry newtons. I was finally here, I thought. The start of the Cascades, after which I'll be in the Sound area and my home. I wasn't sure how I felt about that. I had been looking forward to this immensely, but now that I was here I realized that the familiarity that I had with the region was not a positive. I was on known ground, ground that I had a history with. No longer would newness be my friend and companion.

I still had two hundred miles before I left the Cascades, however, and there was a lot of fabulous ground to cover. I hadn't been to the eastern Pasayten before and had only crossed a small section of the western portion at the end of my PCT hike in 2003. I can still remember, perfectly, my encounter with the Pasayten then. Birdie and I were finished up a low 30 mile day from Cutthroat Pass to the border of the Pasayten. It was our last full day on the PCT. Coming out of a break at Harts Pass I stopped in my tracks at the long view through the Pasayten. I stopped and sat down, despite having taken a break just fifteen minutes ago. Birdie found me sitting by the side of the trail in the tall grass and asked me what was wrong. Nothing, I told her. This was just too beautiful to pass up. I had hiked for more than a hundred days by then and had come all the way from Mexico. I had seen a lot of things and have lived immersed in beauty. And still, after all that, I had not become jaded by beauty. I had to sit that day because the beauty was so immense and, I knew, it was coming to an end very, very shortly. I had this to look forward to over the next eight days. I looked forward to it very, very much.

I didn't need any motivation to get moving this morning, even with the cool air outside my warm sleeping bag. I motored up the road and began to sweat hard as the valley below fell away at my feet and the terrain became more and more subalpine. Two DNR trucks passed me, as did several horse trailers, as I made my way higher and higher. I didn't care about the exertion because I knew that soon I'd be in the Pasayten and in one of the most fantastic hiking areas in the country. Even the clear cut wastelands with signs warning people to put out their fires didn't bother me.

And then I started to smell it. And see it. Smoke. When I first picked it up I had hoped that what I was smelling was coming from cookfires in the campground, but as the air got hazier and hazier I began to worry and finally accepted that there was a forest fire somewhere close by. What wasn't close by, to my surprise, was 14 Mile Campground. The road ended abruptly at a signless trailhead where several horse trailers were parked. I had no idea where I was as I had been following the signs for the camp and didn't think I had missed anything. But, I had. I sat down to look at the map for a while, this one a much better one than the Delorme junk I had been using for road navigation. While I was looking at the map and eating a candy bar a horsetrailer arrived and out spilled two friendly thirtysomethings who where there to pick up some friends who had ridden across part of the Pasayten. Unfortunately, they didn't know where they were either and had only followed the directions given to them by their friends. They were able to tell me, however, that the fire was down on the Colville Indian Reservation, well to my south. It wasn't clear from talking to them if they thought it was natural or part of a ceremony. I thanked them for the info and set out down the closed road, which rapidly turned into a trail. I wasn't sure where I was going, but there was a trail here and it went in generally the right direction.

I found the DNR trucks pulled off on the side of the road, but with no one inside them. They, surely, must know where they were and so I set off in search of the work crews, who couldn't go far given the amount of gear that they would be hauling along. I didn't have to go very far: They came to me. I had moved about fifty feet down an unmarked side trail that they had clearly taken when they started back up it. The first few youths didn't know where they were, but were sure their bosses knew. They were bugging out to go help with the Colville fire and had to hurry. I waited by the trucks for the bosses, but they also didn't know where they were: They were volunteers from Seattle and had followed directions for how to get here. They warned about an electrical storm that was supposed to hit the Pasayten in the later afternoon. I thanked them as well and then set off in my original direction.

My trail quickly degenerated into a muddy, sloppy affair, but a dug, maintained trail nonetheless. A sign on a tree pointed toward "Snowshoe Cabin" and I figured I must be on the right track, even though I never actually saw the cabin. I climbed the swampy, muddy trail, gaining elevation rapidly and incurring the usual sweat. I climbed and climbed and climbed so more, but eventually lost the trail in a maze of horse trails. The heavens opened up and it began to rain steadily, forcing me into rain gear, which of course made me sweat even more. After thirty minutes of rain I hid under a thick tree and for a moment felt sorry for myself. But only for a moment. There was a lot to be happy about.

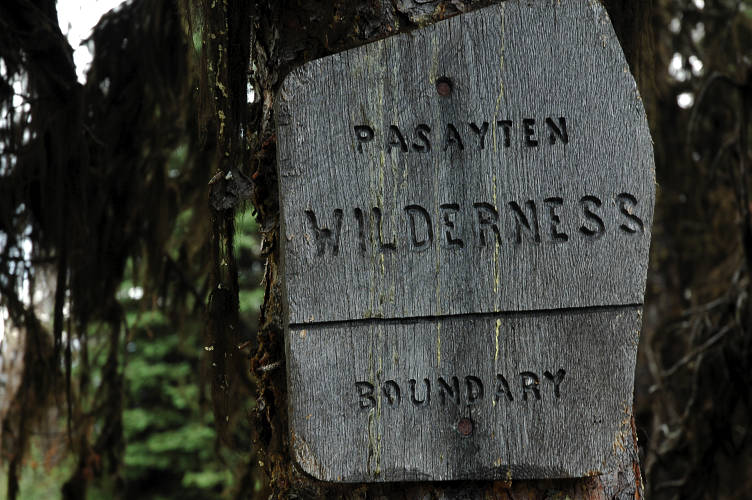

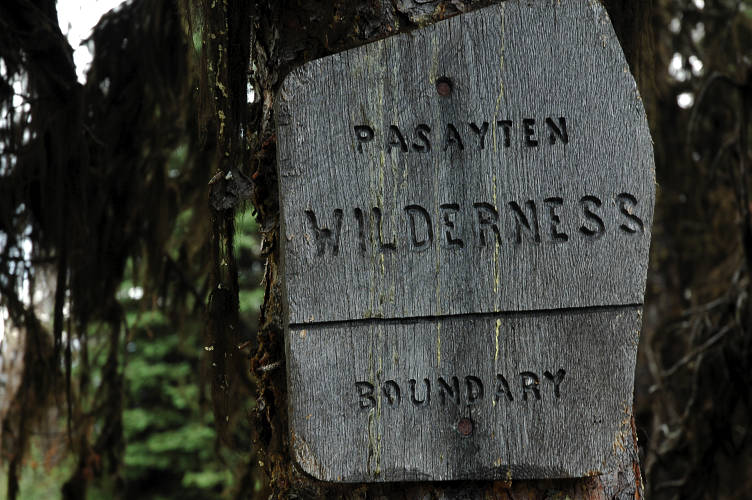

Being successful at being lost is a skill that few people have and even fewer bother to develop. But, it is almost infinitely useful and quite applicable in every day life unlike, say, knowing what a mirapois is. The main thing is to not give in to despair and to have an everlasting faith that you will eventually find your way out. If you start to panic, they your goose is cooked and you might as well sit down and cry. You won't die for another two weeks or so and it is going to be slow and painful. Or, you could just keep going. As my friend Yogi might say, "Don't worry. You're just temporarily misplaced." After fording several swamps in the rain, I crested a small lip and found myself on a plateau where I could see something of the misty mountains in the distance. And a big drop. I took a compass bearing and started moving through the woods as best as I could. This is the second principle of being lost: Don't trust your sense of direction, trust a compass. I followed game trails when I could, but walking through the forest was fairly easy. Occasionally I would end up at cliffs and have to back track, but eventually I ran almost directly into a barbed wire fence with a cattle stile and a big sign welcoming me to the Pasayten.

There was a trail running to it and I wandered down it for a bit to see where it had come from but it faded out and I decided that not many people came from this side, probably for good reason. The rain had gone away, making the hiking much more pleasant. The trail dropped down before traversing along the flanks of a mountain, still in the trees and without views. Although I was tired, both physically and mentally, I wanted to get an open view and confirm where I was on the map rather than staying in limbo for any longer than I had to. After all, I might be on a trail going someplace I didn't want to go! I didn't have to wait long for the trail to break out into the open and give me a vista that I could locate on my map.

I sat down and figured out what had happened, sort of. At some point aliens had transported me from where I was on the road to some place else, and I had magically wandered upon the Snowshoe Cabin trail that was described in the PNT guidebook and that I had been intentionally trying to avoid. If I had bothered to read the guidebook I would have realized that a long time ago. I had taken, more or less, a cross country route to get to the PNT, and then more cross country to get to the Pasayten. But, here I was and the magnificent Horseshoe Basin was in front of me. I had nearly 150 miles of wilderness to traverse to reach Ross Lake and its dam, and then another fifty or so before I hit the Mount Baker Highway. The sun started to come out and I began to explode inside with pure, unrestricted, uncompromised joy.

Horseshoe Basin is a large, open plateau at the far eastern end of the Pasayten and marked, for me, the start of the mountain traverse that led to home. The sheer size of the area, of the view, was remarkable. Although there were mountains hemming it in, they were far off and there was little to obstruct the sight of a hiker passing through. The Pasayten was so large and so remote that weekenders rarely came to it. In order to get here and enjoy it, you needed to come in for a week or more and that kept the riffraff out.

I could see my route, even if not the actual trail. I could see where I would be in thirty minutes and where I would be in a few days time. This was the sort of thing that oppressed settlers in the early days of our country when they left the Mississippi and began the traverse of the Great Plains. An endless sea of grass, without a tree or other obstruction to give comfort to the eye, greeted them. This monotony, as some called it (and still do), broke many of them and reading first hand accounts of settlers one is struck by the dichotomy of opinion: One either loved the Prairie or one loathed it. I suspected that I would have loved it.

I rounded a lake and passed two hikers returning to the tents that I had passed a mile earlier. I was running at maximum happiness in the open air, but took a break from feeling good to notice a storm coming for me. This was the electrical storm that the DNR workers had warmed me about and I had no intention of getting hit with a bolt of lightning that was five times hotter than the surface of the sun. I motored around Rock Mountain, dropping and gaining elevation without, it seemed, any effort at all. When the mind is right, the body has to follow. I stopped to quickly make dinner, for I didn't want to be forced to cook under my tarp and perhaps attract a nighttime visitor or two. As I ate my mashed potatoes I glanced nervously at the skies in between slapping mosquitoes. I'm really back in Washington, I thought. Rain and bugs. No more sunshine and napping under trees for me!

The storm was almost on me, though I could not see any falling rain as yet. I quickly climbed up the trail, which dumped me out onto a gorgeous, open plateau. This would have made for a most excellent camp site, but the weather wasn't going to let me stay up here and the lightning that was sure to come would make it a potentially lethal bedroom. I traversed across the plateau and was battered by the stiff winds that the storm had brought with it. Flashes of lightning starting popping in the valley below me and I quickened my pace, hoping to get down off of the plateau before the storm hit me. Teapot Dome came into view and I knew there was a campsite somewhere near its base. Lightning flashed and the wind blew, and I moved on rather than gawking at the scene.

Although I had passed many places where I could have camped, none of them offered much in the way of weather protection, which is one of the downsides of a tarp: You need some trees or rocks or other natural features to knock down the wind for you. I began dropping down and noticed, at a stream crossing, that there were some clumps of trees nearby that could work. Ten minutes of scouting and I had found a nice, comfortable campsite complete with a great windbreak and with water access close by.

The storm looked like it was going to hold off for a while, so I wandered around and took some photos of its approach and even took the time to wash my feet in the creek. Even though they had been wet all day, they were dirty and muddy from the swamps earlier in the day. The water was cold on my feet, but not unpleasant. I returned to my tarp and huddled in my sleeping bag while I wrote in my journal and read Xenophon for a while. If there was a more pleasant place to spend the night, I couldn't think of it. I had all the smells of the forest to myself and when the storm came, as I knew it would, I would be sheltered from the worst of it by the trees and my tarp. The rain would knock down the smoke and the haze of the Colville fire and tomorrow would hopefully be absolutely gorgeous. I might even get a glimpse of Mount Baker, still more than a week away. I closed my eyes and breathed deeply of the air. I breathed regularly and deeply, through my nose and out through my mouth, rhythmically and naturally. There in the darkness, just breathing. Just so.

There was no mystery about what woke me up during the night. The booming of thunder and the flashing of lightning and the high pitched drumming the rain made on my tarp brought me out of my slumber multiple times. The trees went swish in the high wind. My camp was a good one and I was protected enough from the storm that going back to sleep was easy: I was warm and dry, even if the world outside was unpleasant for the moment.

The storm tapered off around sunrise, but the air was still cold and misty and clouds hung in the valleys below and in the sky overhead. I tuned in NPR on the radio to see if there was any news about the fires or about upcoming weather, but turned it off once I started hiking shortly after 7:45. I was getting a later start than normal, but I was hoping that the mist and clouds would go away before I reached Cathedral Peak. I had never seen the area before, but from looking at the topographic map, I knew it was going to be immaculate.

I hiked quickly to generate some heat and passed a more established campsite, which must correspond to the Dome camp labeled on the map. Mine was far better, I thought. The guidebook's description of the trail didn't correspond to reality (a habitual error, it seems). I didn't quite see how it could have happened, unless it was a typo or production error. Rather than descending to Scheelite Pass, which was described as a rocky gully unsuitable for camping, the trail instead climbs to a broad pass with lots of good, but dry, campsites. And rather than being at a height of 6000 feet, it was more like 7000. Perhaps my map reading was off.

I loped along happy to be where I was, for the light drizzle of the early morning was gone and the weather looked to be stabilizing. The valleys below me were still cloudy and misty, but the clouds above me were beginning to consolidate and actually clear. As expected, I had passed no tents in the morning and didn't expect to see any one for several days, leaving me the sole caretaker of the wilderness.

It took three hours of solid hiking to make it to Tungsten Mine, which was one of the last operations in the area before the land was designated a wilderness. The mine buildings had since been renovated and were cared for by local hikers, riders, and skiers. The main building was a long log cabin where miners would have slept and taken their meals. There was a smaller cabin next to it that various groups had restored, as well as a really swank two seater privy out in the woods.

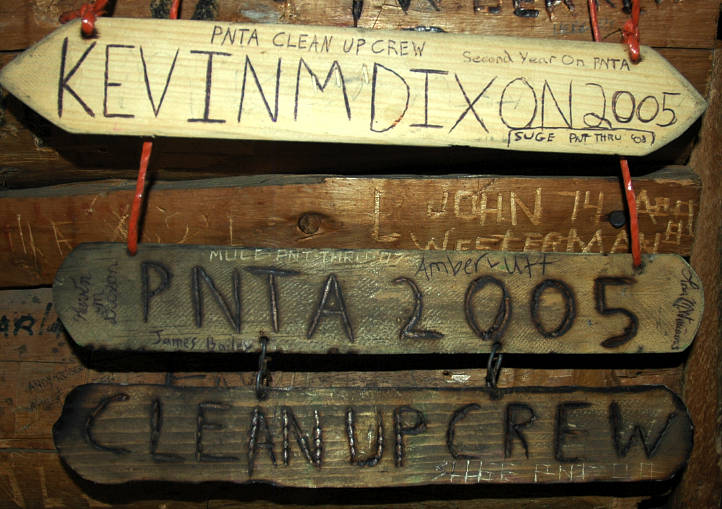

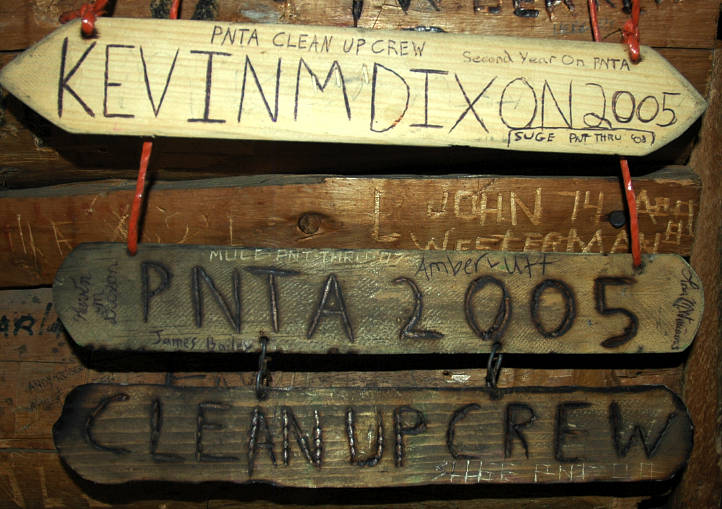

I went inside and dropped my pack, for I intended to wait here until the weather turned solid, even if it took all day. I wasn't about to wander over Apex and Cathedral Passes without being able to savor the rewards at the top. The cabin was covered with carved and written names and I spent thirty minutes wandered the interior looking at the names and dates while munching on a Snickers bar. I found a PNT section and added my name to a few others, including Mule's, whose trail comments had been so helpful to me so far this summer.

I paid a visit to the two seater and wandered around the mine area, looking at the various bits of rusting machinery and other relics of the past. After an hour at the weather looked like it was going to turn fine and I set out once again, enjoying the sunshine after the last few days of rain. The climbing was gentle and I made rapid progress up to the pass, which was another broad, open affair.

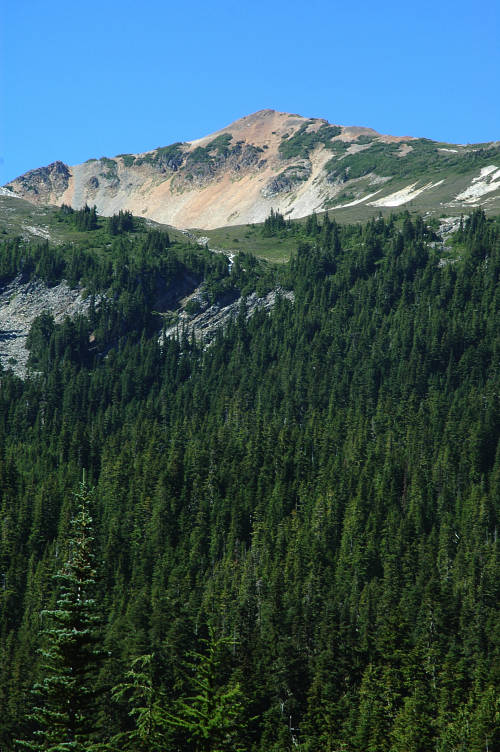

But while it was sunny on my side of the pass, as I moved across it and began to get views of the other side, it was clear that the weather had not gone away at all. It had simply shifted. I passed through a stand of trees and on the other side was the first view of Cathedral Peak. I was stunned at the jaggedness of the mountain, for most of the peaks in the eastern Pasayten had been broad, gentle peaks. Cathedral was a real mountain and it was unlikely to have any easy way to the top.

I pushed along the trail and the views opened up in to the sort of colossal forms that I love so much. The scale was huge. A deep valley fell away at my feet. On the other side was Cathedral Peak, looming, malevolent, hostile. Next to it was Cathedral Pass, broad and open. Flanking that was massive, butte-like Amphitheater Mountain. And overhead were storm clouds, black and dark and threatening. I could see the trail extending for quite some distance. It was going to traverse around to the head of the valley and then curve back around, directly underneath Cathedral, and then climb to the pass.

Given the clouds and yesterday's lightning, I should have been hurrying along. I should have hustled to get to a lower elevation where I might not get zapped by a bolt from the heavens, or pounded by wind driven rain. But I didn't. There would be time later on, like when I went home and put all this foolishness behind me, to run around and be scared of things beyond my control. And so I leisurely strolled down the trail, enjoying every moment of the walk.

Control is more than just deciding what to watch on television or what kind of cheese to put on your burger. Control is more than deciding where to go for a walk or who to talk to or how to spend your evening. A Buddhist monk once told me: "First, let go of your past. Then, let go of your future. Finally, let go of the present.". I could understand the first, even if I couldn't do it. Letting go of the future was about control. Rather than trying to create your future all the time, sometimes it was best simply to let things happen and float along, reacting to what you needed to react to and letting that which doesn't matter slide into the gutter. I had been trying to understand what the last part of the monk's advice would look like, but couldn't. And I've been trying for nearly three years.

If a bolt from the sky was going to hit me and leave me flopping on the side of the trail, then so be it. This wasn't arrogant bravery on my part or sheer stupidity or placid apathy or a careful weighing of the odds. If the rain came and soaked me through, then I would deal with that when the time came. For now, I was going to enjoy the pass. I was going to, as much as possible, embrace the present moment only, and let the future work itself out. This was, fundamentally, why I couldn't understand the last bit of the monk's advice.

I sat on top of a boulder at the pass for a while to cool off and to enjoy the views down to the broad plateau on the other side and the far mountains. I would have to cross them, and their friends on the other side. That is the nature of east-west travel in the West: Your cut across the grain of the land. I was going to have to gain and lose 3000+ feet every time a mountain ridge blocked my path. And I was looking forward to every single on. I dropped down and hiked for thirty minutes to Upper Cathedral Lake, where I took shelter under a thick fir tree from a light rain that was falling. I hadn't eaten at the pass and took the opportunity to munch on some trail mix while watching the light rain bounce on the black water of the pond.

The rain passed and I moved on, though I quickly became lost amidst a slew of unsigned trail junctions, each of which could have passed for the right way. I followed one for a solid mile, but it began to climb away from the right direction and I had to break out the maps to orient myself properly. I spied a trail across the way and it seemed to be running to the right place. If the place hadn't been spectacular, I would have muttered some curses and told myself to be more careful in the future. But I didn't. It was too beautiful out to do that.

The trail I picked up was the right one. It traversed to the far side of the plateau and then began a stready descent into the woods below. I passed a well stocked and carelessly kept campsite, which undoubtedly belonged to a trail maintenance crew, before reaching Spanish Camp, which consisted of a very well locked up log cabin. A few tents were pitched in the area and the place stunk of horse dung. I rested long enough to drink some water and then pushed on, leaving the ugly place behind. I had a climb coming up and, despite knowing that I was going to have to work physically, I was looking forward to getting back above the trees and into the open.

The trail ran me up on to the flanks of a minor hill and traversed up above an open plateau that would have made for an excellent setting for a pioneer novel. Small stream, beautiful timber, a mountain in the backyard for exercise. On the far side of the traverse the trail began to climb steadily via a well engineered series of switchbacks, giving off increasingly better views of the land. Although the climb was fine, it was the summit of Bald Mountain that was the real treat.

The open park lands of Bald Mountain ranked as one of the greatest plateaus that I'd ever had the fortune to traverse. Big Horn plateau, in the Sierra Nevada Mountains, comes to mind. The Arctic Lake plateau in the Northern Coast range. And now Bald Mountain. The lupine were everywhere, scattering their pungent smell to every nook and cranny of the mountain. I would probably only get this smell for another few days, and then it would be gone until next year.

This was not jagged, craggy, desolate alpine land. It was not the classic mountain scenery from the European Alps that we normally identify with the alpine ideal. Rather, this was a life giving, life sustaining, life expanding landscape in which one could revel and frolic and appreciate the simple fact that one is alive and not dead, not stuck in a metal coffin creeping down a freeway after a ten hour day of pushing paper around, electronic or otherwise.

This was a place that, because of its expansiveness, its greenness, its distant mountains, its fragrant wildflowers, even its blue skies and pleasant breeze, all these things gave this place a quality that was undeniable. As much as being a vagrant by the side of the road had tickled my fancy, as much as I had enjoyed meeting people like Becca and Heather and Joe and Jason and John, as much as I had appreciated the aesthetics of unstructured living, it was here, in this land, that I was most naturally at home.

I had sensed this yesterday when I first came into Horseshoe Basin. I felt it, I knew it, now. It was the same feeling that I had when, on the next to last day of my PCT hike, I had to stop and sit by the side of the trail amazed at the sheer beauty of the land and the feeling of comfort that was welling up inside of me. The feeling was palpable and was not simple adrenaline. Besides, what sort of adrenaline rush can you get while lazily strolling at 3 miles per hour? No, this wasn't wishful thinking or some sort of psychological delirium that would pass when I went to bed or ate a cookie or went home. No, the Pasayten was special for other reasons. It was with some sadness that I came to the end of the plateau and stared down into the valley of the Ashnola, 2000 feet below me. But the sadness faded at the sight of the mountains on the other side, where I would be tomorrow morning, in time for the early, clear light.

I went down the nine long switchbacks and lost myself in the forest after the first three. Down and down and down I went, not so much enjoying the easy grade as wishing it might just get me to the bottom quickly. I still had a lot of light left when I arrived at the river and an old shelter that looked like it was about to fall over. Still, I set up camp inside it while my water for diner began to boil. Without a doubt, my tarp would be drier in the event of a storm, but I like sleeping in shelters when no one else is around.

I sat with my back against a log and ate by Broccoli and Cheddar rice mixture, chased down with Raspberry Newtons and cold water from the Ashnola. The sky slowly grew grey and then began to fade into blackness. I had written in my journal and read a bit from Xenophon. I had taken a liking to just sitting at the end of the day and doing nothing. No reading, no writing, no contemplating, no map reading, and certainly no thoughts of what I would do when I had to go back and earn a living. I just sat and felt the breeze on my head and sniffed the air and looked into the growing blackness. It was pleasant to spend ten minutes, or thirty, doing this. It was the opposite of life back in the fake world that we call the Real. It wasn't something I could do for long, for eventually my mind would tell me to go to bed or otherwise to entertain it. But for a while it was quite and restful and I could simply sit and be.

For whatever reason I had not slept well in the shelter, probably because a rodent lived there and my body kept waking me up every time he crawled over me or into my gear looking for food. I don't mind this at all, especially as my food was hung from a rafter, but do mind being woken up consistently through the night. It was cold when the sun came through the tree canopy overhead and revealed a fine mist and thin drizzle. Rule Number Three of Long Distance Hiking is: Only a Great Fool Leaves a Dry Place. I sat and waited on the drizzle, warm in my down, and read maps. Near 8 the drizzle seemed like it was on its way out and I was quickly on my way. I didn't hesitate a the bridge over the Ashnola, though I pity on those without much log walking experience.

I quickly sped up the hill on the other side trying to gain warmth in the cold air of the morning. The trail, as before, was well graded and my rapid pace got me to near the top quickly. As the trail broke through the trees and began a traverse I spotted something moving. With my bad eyes I couldn't quite make out what it was at two hundred yards, but it was large, black, and moving toward me. It took another second to realize it was another human and not a bear. I hadn't expected to meet anyone out here as I was in the heart of the Pasayten and a long way from any road. Kevin, too, was equally surprised to see me. He hadn't seen anyone in twelve days, the length of time he'd been out so far. He was on a long, mostly cross country traverse from the north end of Ross Lake to Chopaka Mountain in the east. He was to finish by the route that I came in, though would end up in Canada and hitch back to his car. We talked for about a half hour and I got some great information about trail conditions further ahead in the valley of the Pasayten River, where there had been a massive burn two summers ago.

Out of the cover of the trees it was absolutely frigid in the hard blowing wind. I stopped and put on my rain jacket and gloves and then continue across the open land, which seemed a direct continuation of Bald Mountain. The cold was biting, and my fingers were going numb, but I was happy. I was content being here in the most beautiful place on Earth. Even a mean old desert rate like Ed Abbey would agree with me. At least, that is, until twenty minutes later when the both of us might repeat the same statement. True beauty is easy to recognize even if it is hard to define.

I was climbing gently toward Peeve Pass, which turned out to be a little notch in a clutch of trees and not really a pass at all. I stopped in the sun on the far side to gather water from a snow melt stream and look over my maps. Talking with Kevin had confirmed an alternate route to the PNT that I had been contemplating. I was going to drop down to Hidden Lakes Basin (how could I resist a name like that) and then climb up and over the Tatoosh Buttes and then down to the Pasayten River. A trail would then take me up to the PCT at Woody Pass. Although I wouldn't be on the PCT for as long as I wanted, I did want to see some other things as well and my route had the advantage of being cleared of the deadfall from the fire in 2006.

A storm was hitting the eastern Pasayten, but it was sunny where I was heading. The route finding looked to be easy, but I underestimated the difficulties. I underestimated them because my usual strategy failed me. This is Rule Number Two of Long Distance Hiking: Never Leave Good Trail for Bad. At an unsigned trail junction I couldn't figure out quite where I was or where to go. I guessed that I was at the junction to Quartz Lake but, as it turned out, I wasn't. I took the left fork which seemed larger and more traveled and happily hiked on. And this lead to a spectacular detour.

My trail led up into some woods and then broke out into an open, craggy hillside where I ascended sharply up to a bald hill with views in every direction. The usual garish display of wildflowers and bulky mountains greeted me. I ran into some horsepackers, whose presence wasn't much of surprise given the distances between trailheads. I continued my traverse (of Sand Ridge, it turns out) and broke into open park land once more.

The Pasayten was getting better and better with every step I took. The mountains were slowly changing into the glaciated North Cascades which, with their sister peaks across the way in Canada, are the very definition of a classic alpine landscape. Some may prefer the expanses of naked granite found in the Sierra Nevada, but there are no glaciers there and far too many fat tourists waddling about.

My trail began to fade out as I entered an enormous, open park where the way was marked by cairns and posts instead of an actual tread. In the far distance was a small notch and I assumed that that was my next destination. I was also looking for something called Bunker Hill which seemed to match up in my mind with the sloping hill on the right. Trail must go up there, I thought greedily, looking forward to an open alpine ramble.

The park was enormous and I enjoyed every moment I had in it. The lupine were out and fragrant as before, but a stiff wind was blowing, dropping their pungency to merely outstanding, rather than intoxicating, levels. A few snow melt streams crossed the park, but there were no permanent sources of water here and hence little opportunity for anyone to build a permanent home here. It took me some time to cross the park and begin the ascent to the notch. I had a trail once more, but the climbing was a bit stiffer than normal and I reached the top in a full lather, despite the cooling wind. And then I realized something was wrong. I didn't let it bother me for a moment while I enjoyed the views down to the parkland I had just covered.

What was bothering me was the view on the other side. I had been expecting a trail up from the notch onto the ridge and then a ramble to what I thought was Bunker Hill. But, the trail clearly continued on the other side of the notch and then on down to a trail big enough for me to see in the distance. There was a faint climbers trail heading up the ridge, but nothing established. I dropped my pack and tried to think, tried to reason out where I was and where I was heading. It took about three minutes of looking at the map to realize that I wasn't anywhere near the PNT: The mountains were on the wrong side.

I was frustrated and for a few minutes gave into a self satisfying anger. But this passed as I realized that I had a simple choice: Go back or go forward. There was big trail ahead, so forward I went. I dropped down off the pass onto the open slopes below and made a direct line to the big trail. I intersected the big trail and followed it up slope for a moment to confirm where it went: To the gentle pass above at the head of the valley. My compass told me that was clearly the wrong direction, so I turned back and followed it downslope for a bit until I ran into a tree than had a beat sign on it saying Hidden Lakes. But the arrow pointed along a cairned route, not a trail.

I sat and had some lunch, then scouted along the main trail for a while. It seemed to run up to a pass that was oriented more or less in the direction I wanted to go. Actually, it wasn't. But, I didn't want to leave the good trail for a possibly abandoned track that, given the fire two years ago, would be a nightmare lower down. I recovered my pack and set out on the big trail. It was only 10 minutes to a high pass. On the other side, the trail did go, more or less, about in the direction I wanted to go. I dropped off the pass and began to rapidly lose elevation on the switchbacked trail. A half mile down the way, and still no sign to tell me where I was. As fortune would have it a man with a big pack was walking slowly in my direction and I was able to, with some embarrassment, find out that I had just come over Larch Pass. I groaned, turned around, and took off at a furious pace to get back to the pass.

Looking at the map later on it was obvious where I had done wrong. I had turned the side of Sand Ridge and traversed across Whistler Basin (the big park) and the cut over Whistler Pass. The beat sign was an actual trail junction and was the itnersection of trails 502 and 548. I reached the tree and began the cairned route down into the valley below. The trail improved as it descended and it was clear that trail crews had been working hard in the area over the last year. Despite the heavy burn area, there was nary a log to hop over.

Every time I passed a cut log, I thanked whatever crew had cut the log. Being a designated wilderness, motorized gizmos are not allowed, except in the case of rescue or fire suppression or other emergency. The trail crews came in with horse or mule support and cut the trees out with cross cut saws, using metal chains and pulleys to move the larger logs once they were cut. It was a laborious job that didn't pay enough, especially as many of the trail crews were volunteers working for food and merit.

After a few hours of hiking through the forest I reached an intersection and made a left, aiming for Hidden Lakes. The trail was very brushy and I began to worry about finding the right intersection up to Tatoosh Buttes in the thick of the Green. I hadn't caught sight of a lake until one moment I burst through the trees and there was the first of them. As far as lakes go, it wasn't an especially stunning example. It was overcast and it was windy and the light wasn't flattering and I was tired and...But true beauty is always there. Perhaps with the right conditions I might have found the lake more attractive.

The brushy trail continued and my worries increased. If it rained over night, or there was any condensation, walking though the chest high brush would be like taking a shower. I stopped and ate some wild raspberries to make myself feel better. Right by the bush was a little, barely noticeable, trail heading through the thickness. I wouldn't have noticed it if I hadn't been looked for it. I hiked up it for a little bit until it was clear that it was what I wanted, then I turned around to head to the next lake. After all, it was starting to get dark and I was pushing up against 30 miles for the day, including my detour over Larch Pass. And I hadn't yet had my dinner.

The last lake was, unfortunately, even uglier than the first two. I managed to bushwhack over to a dried mud flat and set up camp, hoping that it wouldn't rain. I had a nice view of a mountain, though. After setting up the tarp I filtered lake water and started my pot boiling for the night's feast of instant mashed potatoes and raspberry newtons. Tomorrow was going to be a good day. Not only would I climb over the Tatoosh Buttes, but I would also hit the PCT at one of its most scenic places. And this started me thinking. The best parts of the PNT, I reasoned, were right here and in the Olympics. The route through the North Cascades wasn't especially imaginative or interesting, and I hiked all the time in the Olympics. Maybe I should try a really big alternate?

I could hike to the PCT, which more or less is the western boundary of the Pasayten, with only one major peak left before the descent to Ross Lake. Instead, I could hike the PCT south to Snoqualmie Pass, a distance of about 200 miles or so. This was one of the best long segments on the PCT and I could follow it without maps to Stehekin, where I could find something to guide me around Glacier Peak and the re-route that was forced due to flooding three months after I finished in 2003. From Snoqualmie Pass it wasn't clear what to do, but I possibly hike due west using a combination of trails and roads and actually walk home. But if I did that, I wouldn't get to end at the Pacific, which had a certain symbolic pull on me. Or, I could get really ambitious and hike the PCT south to the Three Sisters area and then walk to my father's place in Keizer. I could have enough time to do that, I thought. Or maybe take the PCT north into Canada and then hike, somehow, to Vancouver. Then, I could take the ferry across to Victoria and explore Vancouver Island on foot before catching another ferry back to the States. I could do any of these and feel good about what I had done. I wasn't constrained by a pre-determined line. Rather, I had the freedom to choose what to do and was answerable only to my own conscience. I was quite content with having that as a possession.

I didn't need much coaxing to get out of my sleeping bag and begin to break down camp on the dried mudflat in the very frosty air of the valley. Hot air rises. Cold air sinks. I was in a big sink. I made tea, of course, but my mind was already wandering far away. Above me was a steep climb to the Tatoosh Buttes where I'd get my first good view of home and the PCT. The maps made the place look special: Big, open, expansive, and with enormous views in every direction. And then, later in the day, I'd be back on the PCT, at least for a short while. I set off at a fast clip and gained elevation rapidly until the last 500 feet of so, when the gradient increased enough for my body to remind my head of what I was doing. But when I topped out, I was amazed at what I could see.

Truthfully, I could smell the top before I could see it. The lupine were so dense, and my nose so used to them, that the scent of open wildflower fields were had an easy ten minutes before I actually got to them. In every direction there were lupine and paintbrush and lilies and other gaudy plants whose names I didn't know. The air was bracing at this elevation and my breath hung in the air along with the flowerscent. Had the land been warmed by the sun even a little, the aroma might have forced me to to sit under a tree for an hour or three and laze away the day.

The Tatoosh Buttes were really more of an open parkland than a butte and I loped along, nay, almost skipped along, the faint path that carved its way across the top of them. I felt like dancing to the tune that was running through blood and skin and bones and hair and heart and mind. It welled up through my feet and into my legs and coursed through my core and then spewed out of my arms and hand. It wasn't metaphysical and symbolic and I wasn't on acid. It was palpable.

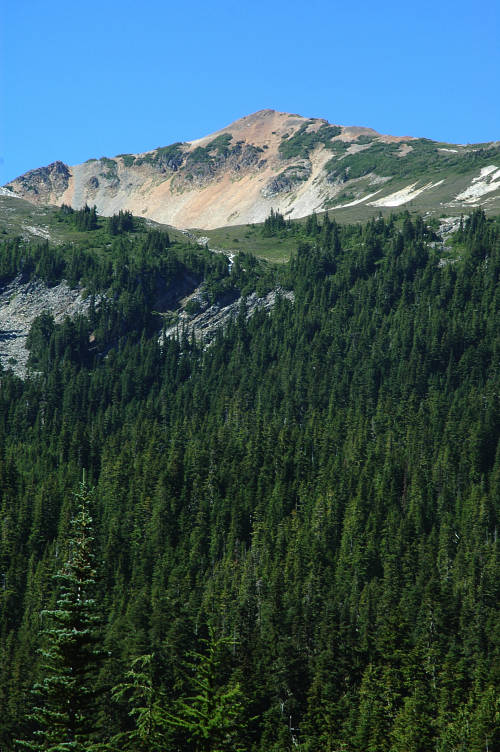

In the distance loomed a hulking mountain with obvious glaciers on it. That was my marker, my little sweetie. It was the first true sign of the North Cascades. Home. I didn't know what mountain it could be. It wasn't Shuksan, for Baker wasn't yet in good view. Its name could wait until later. It was still far away. Thirty crow miles? Fifty? In the clear morning air, I couldn't easily determine distance and the rational part of my brain had shut off when I first smelled the lupine.

I reached a junction where the trail I had been following was crossed off and a stake-post route took off to the right. I followed it through the grassy parkland for a while, lost the track, found it again, then lost it again. A game trail eventually led me to another track which went in the direction that I wanted to go.

The track led me on a long traverse across the hill side. The entire Cascade Crest was laid open for me to see. The yawning, glacially carved valleys sprang off of the Pasayten River valley below me, running toward passes on the Crest. The PCT ran along or near the crest and one could join it almost anywhere.

The day was slowly warming on top of the Buttes. I had been hiking for nearly three hours and decided to treat myself to a rest in the sun in a patch of wildflowers. I put my pack under my head and took up an indolent pose on the grass to rest for a while now that the temperature was more agreeable to sloth. It is a rare occasion in the artificial world we've constructed when you are doing exactly what you want to be doing. That is, when it is impossible to imagine doing anything more enjoyable than what you are at this very moment. But it happens frequently when you live out of doors in a place as beautiful as this. Laying in the flower patch was one of those moments. Well, really the whole morning had been one. And I didn't imagine it would end anytime soon.

I filled my water bag with some pure snow melt nearby and set out down the trail as it slowly led off of the Buttes and down toward the Pasayten River valley. The valley had burned hard in 2006 and the fire had stretched for quite some ways up the Buttes, which was probably the reason for the stake-post trail re-route early.

The trail led me through burned out stands of trees that had been filled in with fireweed, an especially flamboyant plant, but one that it lacking almost completely in aroma. At what point do words fail? To be honest, at the beginning. Words are good for describing things that do not exist in the sensory world. Photographs are almost worse than words. It is better to go out and see things for yourself, to experience everything that a particular place and time have to offer. Sadly enough, most people need words and images for they will never experience something like the Pasayten first hand. But let me try to give some encouragement anyways.

The Pasayten Wilderness is the single greatest expanse of hiking terrain anywhere in the United States. The hike over the Tatoosh Buttes is one of the top three visually appealing hikes anywhere in the world. But the trail over it isn't well worn. This isn't a commonly hiked route. Maybe I'm spoiling this insider secret for people. But the place is that good. It is worth it, in every sense of the word. Go there. See it. Smell it. Breath every part of it into you being and take it with you as a remedy for a dreary day.

An hour later I sat on top of a bridge over the Pasayten River resting my feet and my mind for the climb to the PCT at Woody Pass. Although a bit further south along the PCT than intended, the detour was well worth it for the Buttes. I ate some food and drank water from a nearby feeder stream while looking at my maps. My face was permanently moulded into a smile. I didn't think it would distort into anything else for another day or two. Or a week.

The first thing I noticed about Trail 435 was the bear scat. There was a lot of it. Some was new, some was old. A nice, neat pile every two or three minutes, centered on the barely used, hard to follow trail. In some places the trail was, in fact, a trail. In others it was more of an idea. Someone thought a path might be nice to follow, but hadn't built one. I was just following their thought. The picture below shows a typical segment of trail. I know, there is no obvious path here. But it isn't that hard to follow if you know what to look for. The track actually goes just to the right of the clump of trees on the left side of the photo.

The scat was very real and I had to do something about it. So the wilderness rang with my singing... er, screeching. I can't remember a full song, or the lyrics to even fragments of a song. But cutting and pasting between songs is fun, at least as long as no one is there to hear the results. There was so much scat on the trail that it was not possible to be the work of a single ursine. Rather, the lack of human and horse use probably made this a thoroughfare for wildlife making their way between the east and west slopes of the Cascades. After two hours I stopped at a fine mountain creek and drank my fill of the water. Behind me were the Buttes, blocking the view to the eastern Pasayten.

And in front of me, across a wide cirque, was Rock Pass and the PCT. It was close as the crow flies, but there was a yawning gulf in between it and I. Woody Pass was on my side, but it was out of view, blocked by the trees that cluttered the slopes. I was walking home, both literally and figuratively at this point. The tension was building inside of me and I took off racing for the pass.

I could see the PCT carved into the pass as I broke through the last bit of trees and began the traverse over toward Woody itself. It came breaking through from the north, running south, dropping and zigzagging before climbing once more to Rock Pass, where I would be in not very long. The junction wasn't even marked. But a few feet to the south was a ramrod tree with an old PCT trail sign that was partially consumed by the tree. I was home.

The PCT was a formative event in my life. It occurred not when I was young, but rather at the moment when I should have been starting my career as a well grounded member of the middle class. I was done with graduate school and had a good job with solid prospects for a bright future in mathematics. But the PCT realigned, or perhaps completed the realignment, of my desires for my life. It helped me see things from a different perspective and made me aware, fully aware, that there were pursuits in life more important than those I had previously chased.

But the PCT isn't a person. It isn't a book or treatise or a seminar. It isn't something that gives out information or raises awareness. The PCT, or anything like it, is a process. In order to grow and learn, the individual has to do the process and that takes time. I was the person who realigned, who learned, who grew. The PCT was the medium through which I did those things, but I was the active agent. I changed myself, discovered what it was that I wanted, and created the drive to make the necessary changes. The complete immersion into beauty, the de-valuation of material possessions, and the community that the PCT fostered were necessary for me. But so was the time that I had.

And so even if the PCT isn't my physical home, it is a metaphysical one. It is one of the places where I was nurtured, grew up, matured, and eventually left. Coming back to the PCT was like coming home once again. There are only fond memories at a homecoming and I couldn't have remembered an unpleasant time on the PCT even if I had tried. This section of trail, in particular, was powerful. From Rock Pass I was only a day hike from the border and the end of my life on the PCT. Now, if I hiked south...

On the other side of Rock Pass the PCT ran along forever to the south, carving its way above a huge, glacial valley that sparkled with a green that would have made even the most pessimistic Irishman smile. I could follow the PCT with some ease, I thought. I didn't have to turn west tomorrow and head out of the Cascades and toward saltwater. My thoughts from yesterday came back to me. I could hike south until I decided to stop. Until I wanted to go elsewhere. I could stay at home until forced to leave by time or desire.

The mountains in the distance reminded me of my climbing friends at home. I didn't know what range I was looking at, but there were almost certainly people scaling them. Maybe people I knew. I had begun to form bonds of community at home and there were people who missed me there. I missed them as well. And this was progress for me. These mountains, even if I didn't know their names, were another sort of home for me: They were the home of the present, and of the future.

I hiked along in a mood that anyone else would describe as emotional for another thirty minutes. The trail bent itself into a draw where a perfect ribbon of crystal water came down from above. I dropped my pack in the sun nearby and gathered water for dinner. Even though it was early, I wanted to camp in the perfect place tonight and that meant not being dependent on a close water source. I ate slowly and completely, chewing each bit of neon orange macaroni and cheese, savoring the salty, artificial flavor. A place must be especially stunning and the mood incredibly good to enjoy such a dining experience. I lingered after eating, not wanting to leave the draw. I relaxed with my feet up. And found my campsite.

I could see the PCT snaking along the lush hillside. Below it was an open, grassy plateau that looked like it might drop off into the nothingness of the deep valley. It would be the spot. I packed my gear quickly and filled my water bag for the night and began the walk over to the spot. It was only two thirds of a mile or so and turned out to be closer to the PCT that I thought: The trail actually dropped to it and then plunged off the plateau for a traverse to Holman Pass.

A hundred yards off trail I found a gorgeous spot, perfectly flat, to pitch my tarp and set up camp. It was barely after 6 pm and I had a lot of time to sit and enjoy the view and to think about the past. More importantly, I had time to think about the future. I was tempted to continue south on the PCT and to let the PNT be. I hadn't been following it much anyways. After an hour of thought I decided, however, to continue to the Pacific. I had enjoyed the hobo life east of the Cascades and would have to live it again for the section between the Cascades and the Olympics. Moreover, the Pacific Ocean was a powerful symbol for me: It was the end of westward expansion.

But there was a more important reason: If I continued south on the PCT I would be in danger of trying to relive a moment in time that was gone forever, rather than trying to live each day as strongly as possible. My future decided, I left it. I left the past as well. I laid in the grass outside my tarp and watched the sun set on the mountains in the distance. I wasn't doing anything. I was being. And that was important to me. When it got too cold, I snuggled into my sleeping bag and pulled my hat close down over my ears. Even with all of the nostalgia, I was firmly rooted in the present. The past was a part of me and the future was in front of me, but the present was where I was, heart, mind, and body. Complete.

It was frigid outside of my sleeping bag. The cold air and the lack of desire to leave home kept me in my sleeping bag until the late hour of 7 am. The PCT dropped off the plateau and into the trees almost immediately and I had to hike quickly through the shaded land. I reached Holman Pass and stopped briefly to look at the trail junction sign. If I continued south I would reach Harts Pass this morning and probably arrive at Stehekin tomorrow afternoon. I knew that I had to turn off the PCT, but for once the knowledge of certainty didn't help me. I lingered.

The trail dropped me down into a thickly vegetated gully where a decrepit old cabin lay in ruins. It was flopped over on its side, with a collapsed door and a broken roof. I laughed at Ron Strickland's expense. I had been waiting to see this cabin for several years after a friend had told me about the joke that another friend of mine had played on him. Strickland, the guidebook author, works as a part time oral historian and has published two books about the history of the Pacific Northwest as told to him by various old time residents. Mad Monte Dodge told him that the cabin was put up by a sheepherder named Yon Dodge who built the cabin so small because he was a midget. Strickland promptly put the tidbit into the PNT guidebook where it has entertained those in the know ever since.

Beyond the cabin I crossed a river on a log bridge near some tents whose residents were still sleeping. I began the steep climb up the other side toward Sky Pilot Pass, hoping that I would reach the sunshine soon. My route today would have a lot of up and down to it now that I was leaving the parklands of the Pasayten Wilderness for the sharp ridges of the North Cascades. There were no views on top and after a short rest I dropped down the other side and began the down and up to Deception Pass. The climb was steep, but this time there was a reward on top: A view the short route to Devil's Pass.

The route was more of a traverse than a down and up and had frequent views through the trees to the mountains in the area, including hulking Jack Mountain. That was the peak that had told me I was home in the Cascades. From up close, it looked enormous, with large glaciers clinging to it and an odd combination of sharpness and rubble.

I was tiring already. After the highs of the last few days, my emotional level was drooping and dragging my body down with it. Much of my enthusiasm seemed to have departed from me when I left the PCT. It wasn't fair to today, but it was there nonetheless. At a break in the trees I got my first solid view of Mount Baker. It didn't do anything for my stunted energy levels. It was just there.

I reached Devils Pass and walked past the trail junction that I was supposed to take. I only realized this when the trail I was on began to climb up the wrong side of a ridge. My head was elsewhere. Jack Mountain dominated the landscape as I made my way down the other side and began a traverse toward Devils Dome, whose name alone should have gotten me excited. I trudged along through the beautiful land, tired and resigned, rather than joyful and happy.

The trail wound its way through a few open parks and then climbed up to a plateau from which Devils Dome could be seen. A few clouds overhead. And lethargy. I sat by the side of the trail for a snack and water. I needed to pull things together for the day was still young and I had quite some distance to go to get to Ross Lake, where I intended to spend the night.

Clouds overhead, the first in many days, didn't help my mood much. I didn't know why I was so depressed and tired. It felt like I was forcing my body to do something that it didn't want to do. Maybe I was still in the PCT's gravity well. Maybe I was actually not looking forward to the Puget Sound region. Maybe I didn't want to leave the wilderness for the hobo life once again. I reached the top of Devils Dome and took another rest at a perfect campsite. Water was flowing from snowmelt just below it and it would have made for a great bedroom for a night. This cheered me somewhat, as did some more food and water. But I was forcing things.

I crossed over and began the descent down to Ross Lake without much happiness. The lake itself was part of an enormous gash in the Cascades formed by the Skagit River, one of the main sources of water for the Puget Sound area. The river was dammed in multiple places, but Ross Lake was one of the largest reservoirs. It was nearly a vertical mile beneath me.

I began the descent in the same joyless mood that had captured me once I left Holman Pass. Even the far side of Jack Mountain couldn't cheer me.

The skies were clouding up thick. I didn't care if it rained on me now. I left the Pasayten near a view of the lake. A sign told me so. My heart was tired.

I dropped lower and lower and the heat began to build. After the dry air of the eastern side of the Pasayten, and indeed of the entire region stretching to the Rocky Mountains, the thick, humid air crushed down upon me and I began to sweat profusely. The plants began to change, with mosses and ferns growing thickly, along with my nemesis, the Devils Club. I didn't have the energy to knock any over.

But at the lake itself I started to revive. And it began to a simple handful of huckleberries.

it wasn't the sugar in them, for I had been eating sugary foods all day. It wasn't the calories, for they had less than thirty in them combined. I think, rather, that it was the taste of something alive that did it. I had walked out of Oroville a long, long time ago, more than 150 miles in my past. Since then I had been eating only backpacking food and now I had something living to eat. If I had brained a squirrel with a rock and eaten its bloody flesh raw I probably would have had the same feeling. At least this is what I told myself. The reason didn't really matter, though. The result did.

The trail along the lake was pleasant and easy, with frequent views of, well, the water: The mountains were hidden behind the foothills ringing the lake. But change, I suppose was good for a person. I was in the Ross Lake National Recreation Area, which meant that I was supposed to have a piece of paper called a permit allowing me to camp on the land. My land. But only in designated places where someone in an air conditioned office had determined it was appropriate. They did so with a clear conscience, without thinking. They assumed people were pigs and would destroy everything that they could unless told otherwise. And so they made regulations and drew boundaries in the name of preservation. Maybe I didn't know any better, but I thought I did.

Just beyond a long suspension bridge over deep inlet I found an excellent cascading spring and had a seat for dinner and a drink. I had seen very few people since I entered the Pasayten but almost the instant after I set my stove and pot on the trail and began boiling water a hiker carrying a huge external frame pack and wearing blue jeans came walking down the trail. He grunted as he went by and quickly disappeared from sight. I wasn't sure if he was unfriendly, mute, or just didn't want to talk to anyone. It didn't matter, but it gave me something to ponder as I ate instant mashed potatoes and drank the excellent water.

The rest did me good and I felt right once again, for the first time since leaving the PCT in the morning. The air was hot at the low elevation of the lake and I found myself sweating just hiking the flat trail along the lakeshore. The trail bobbed inland for a while before returning to a lakeside campsite used by boaters. Like the man in the jeans, I didn't really want to talk to anyone and continued up the trail for another forty minutes to a campsite solidly in the woods by a raging creek. Although viewless, it would provide nice white noise for my sleep.

I've got only two full days and a morning until leaving the North Cascades and reaching my next resupply point at Glacier, WA. The town itself is micro sized, consisting of a store and two restaurants and a PO. But the store has a great microbrew selection and both restaurants are famous for their plentiful food. The only problem was where to stay and where to rest. My body was starting to tire under the continuous marathon sized days I was putting in and I would need to rest before pushing on. There were National Forest campgrounds, but not within easy walking distance of the townsite. But that was a problem for later. For next week. I still had more than 70 miles to hike to get to the Mount Baker Highway and Glacier, with several large passes between me and it as well as a touron resort to survive.

The deer was within ten feet of me. Perched as I was upon the open air toilet of the campground I couldn't do a whole lot to the deer other than swear at it. It wasn't intimidated by me and continued to stare at me with its black eyes, hoping and pleading for a handout. I finished my morning duties, grabbed a rock, and threw it at the deer's head. The rock made a thump on the ribs of the deer and it sprung away. It was actually hot this morning, which wasn't a good sign for the day. The Pasayten had been perfect temperature-wise, but now I was I was going to roast once more.

The lowlands of the Ross Lake area grew thick and green, taking advantage of the warm temperatures and abundant rainfall of the area. Not being a fern or a patch of moss I didn't like the humid environment much and found myself quickly soaked in sweat, despite the early morning hour. The green-ness of everything was pleasing, but after so much time spent in the open parklands of the high country it was hard not to feel confined and restricted by the rainforest.

It didn't take long to reach the end of the lakeshore trail and I stood, agape, at a parking lot watching cars rush by along HWY 20. I had passed HWY way back near Republic and here I was once more. I didn't actually set foot or cross it and my roadless streak was preserved. The Happy Panther trail paralleled the road for five plus miles to the resort and the dam itself. The sounds of the highway were frequent, but after a mile or two the trail ran inland and I escaped the clatter.

The trail was actually quite pleasant and a cool breeze was blowing off of the lake. It wasn't stunning, but it was pleasant. As I neared the dam the resort came into view as well, with large numbers of permanent house boats and other buildings for the tourists to stay in. The resort accepts mail drops for PNT hikers, but I didn't see the reason for sending one: Glacier was only fifty miles away at this point.

I dropped out from the woods and hit a maintenance road for the dam. The heat of the day was beginning to build and with it my mood was beginning to sour. It wasn't just the heat, but also the presence of the dam and the resort and the tourists than were wandering around looking at each other and wondering who in the world I could be. It isn't that I dislike dams or tourists in sandals and polo shirts, but rather the transition from the Pasayten to the dam was heart breaking.

I walked out onto the dam and crossed to the middle section where I took a seat on bench and looked at the mountains to the south. A few people looked at me, but for the most part I was ignored. I had intended to take a nice break on the dam, but I started to feel nervous and quickly got up and crossed to the other side where my new trail started.

I hiked quickly up the trail, grunting at the tourists I passed, just as the man in the jeans yesterday had grunted at me, and sped past the junction with the trail to the resort. Safely on the other side, I took a seat in the shade and rested from the morning's hike. I was alone and I was happy. If other distance hikers were around I would have welcomed their company. But I didn't want to smell deodorant or laundry detergent or explain that it really was safe to hike in running shoes or tell them what I ate every day or what I did with toilet paper. I rested in the shade for an hour and plotted out a route that, though on roads, would get me to Puget Sound quickly and avoid the logging areas south of Mount Baker that the PNT took. The PNT was mostly on roads, though unpaved, anyways.

After my long lunch I felt the heat of the day intensely and was drenched once more. Many backpackers passed in the opposite direction. I couldn't understand this. In the Pasayten, the greatest hiking region in the United States, I had seen almost no one. The Pasayten was gorgeous, open, free of permits, and pleasantly cool. Ross Lake NRA required permits, was closed in, hot, and not especially scenic. Yet I had already passed far more hikers and backpackers since I'd been in the NRA than in the whole of the Pasayten. It didn't make a lot of sense to me and so I suspected that someone wrote a guidebook detailing this particular hike.

My confusion was only to increase. I crossed the Big Beaver river and the land turned to swamp. Soupy ground with many insects and spider webs (face level for me but below the other hikers who had passed through before) and even more humidity. My shirt was translucent with sweat and the misery of the hike was easily the greatest of the trip. I would rather have road walked from Oroville to Loomis once again. The swamp ran on for two miles and then a short climb brought me into slightly drier terrain. I stopped to cook dinner at a creek, but this was mostly to do something other than suffer rather than from a desire to eat.

Around 7:30 I finally stumbled into Luna Camp where there were a collection of tents. I found a spot to camp and pitched my tarp, grumbling about the general ugliness of the area and the poor hiking. I was complaining only to myself, but it made me feel a little better. I stripped off my shirt and hung it on the front guyline of my tarp to try to dry overnight. Not likely. The map wasn't encouraging and it looked like I would be crawling through the lowlands for most of the day, with only a climb to Whatcom Pass to break up the confining forest. For the first time on the trip I wasn't looking forward to the next day, to the next bend in the trail, to the next whatever. For the first time I thought of the stretch ahead as only land to be pushed through, not as an opportunity to see and do something new. This was not good.

My mood had improved slightly. Probably because I was heading uphill where it was cooler and less swampy. I realized that at some point yesterday I had crossed into the North Cascades National Park and was once again permit-less. The North Cascades are a climbers paradise, but so far a hikers nightmare. The route up to Beaver Pass was gentle and forested and fully in the shade. Pleasant pine smell. I was grasping for something good to think about it, but could only come up with the idea that it was better than what had come before. I passed a cabin and began dropping down through the woods toward the Little Beaver Valley.