Wealth

Glacier, WA to Port Townsend, WA

August 16, 2008

I sat outside the store waiting for it to open with a group of locals who make this a morning ritual. A flea market was being set up in the parking lot and it looked like there would be games and prizes and even foot races. I had slept well under the stars by the banks of the creek and had seriously considered taking a day off here in town. But saltwater was really close and I could get to it tomorrow if I left this morning and walked pavement for a while. My plan was to take a direct route to Lake Whatcom, about thirty miles distant, and camp there for the night, either in a park, at a boat launch, or jungled up in the woods like I had last night. The next day I'd cross I-5 and make it to Samish Bay, where I would rejoin the PNT, cutting off about 90 miles of logging land hiking.

The store finally opened and the locals and I piled in to get coffee and pastries from the new crew of beautiful women who had replaced the night crew of equally beautiful women. I talked with one about my route so far and where I was going. The Baker-Bellingham trail was still under construction, but once finished it would be a great route to the Sound itself and, I suspected, would obviate the PNT to a large degree. I sat outside eating and drinking coffee, then got a re-fill for the road and set out around 9 am.

The road was quiet still and the terrain flat and shaded, providing excellent walking. I grooved along to the sounds of the radio, the caffeine from the coffee hitting me hard after so many days with only weak tea in the morning. Except for a few long trails of cyclists, some more than three dozen herd members long, the walking was pleasant through the hamlet of Maple Falls. But then the sun and the cars came out and I began to slowly, at first, fry on the hard top. The shady trees departed as I left forest land for the open farm and ranch lands of a broad valley.

Along with the shade had gone the shoulder and I found myself separated from the speeding cars by only a few inches at times. I stopped at one gas station for two liters of cold liquid, and then at another only an hour later for more liquid. A man stopped and offered me a ride to Bellingham. If I was smarter than a typical rock I would have taken it, but humans are among the more stupid creatures on earth and I foolishly marched on. Later on, when I was in really bad straits, I realized that I hadn't take the ride because I wasn't going to Bellingham. All that nonsense from earlier in the summer about making things up as I went was just rubbish!

The day grew long and the traffic, and heat, increased to amazing levels. It was easily as hot as the road walk from Oroville to Loomis on the other side of the Cascades, but with ten times the number of cars. And cyclists. I started taking more frequent breaks and found myself short on water. Nearing 25 miles for the day I took a break in the shade of some bushes and realized that I would either have to stop at a house for water if I wanted to continue. I drank the last of my superheated water and hoped that there was store at Acme, which was shown as microdot on my map. I was still, maybe, four miles short of it. If it didn't have a store or a place where I could get water, I faced the very real possibility of heat exhaustion or sun stroke. The cars had been getting closer and closer and I had begun to fear that I might get clipped. I started walking, looking for a house where I could ask for water. Simple water.

Five minutes after I began walking I noticed a gold Subaru Outback stopped on the other side of the road about a hundred yards up. The driver was standing outside of it, leaning against the body, waiting for me. As I drew closer the woman smiled and waved me over. "You need a ride," she said. It wasn't a question. It was a statement. I smiled and got in. She had two dogs with her and had seen me walking this morning as she drove up to Mount Baker to let the dogs play in the snow.The heat was setting records throughout the Sound region and she just couldn't let me walk on through it knowing that she could help me without much effort. I told her about my trip and where I was going to and she insisted on giving me a lift all the way to Lake Whatcom.

We sped past Acme, which did have a store, and continued for another five miles to Wickersham. I had underestimated the distance to Lake Whatcom, for it was another few miles beyond the junction to the lake. I would have made it around dark, I supposed, which would have been for the best since there wasn't a sign of public land anywhere. Except one section of the lake, everything was private property. A few people, I supposed, had their primary residence here. But most of the palatial estates looked like vacation homes: I had a lot of practice this summer with spotting vacation homes.Their was a section for the public, it seemed, but it was covered with RVs, tents, and other people having a Sunday evening party. Apparently Monday was a Canadian civil holiday and the entire population of Vancouver under twenty two years of age had come across the border for a party now that their currency was strong against the American peso.

The woman drove me past the lake and dropped me at a grocery store where I could re-hydrate before facing the problem of where to spend the night, for I wasn't going to do so at the human zoo by the lake itself. I thanked her profusely for the ride, but it didn't seem to be necessary. Before she left she got a quizzical look on her face like she was trying to understand something that hadn't occurred to her until that moment, something that had snuck up on her. She couldn't understand, she told me, why we kept the public away from natural resources like the lake. "Why should only the wealthy have access?" If everyone had a car, they could just drive somewhere else where there was public land. What had hit her, I suspected, was that she realized that because I was on foot, I couldn't just get to public land to spend the night. Because of our private property system, I was being forced to break the law just to sleep. I assured her that I would be careful and that something would work. I waved as she sped off.

I dropped my pack outside of the grocery and went in for two liters of blue-flavor sports drink. I was severely dehydrated, but only temporarily. I had been able to correct the problem before it became one that would require several days of recovery. The woman working the counter was named Laura and, after, drinking one of the liters, I hit her up for information about the area. You don't just lay into someone with an abrupt, "I'm homeless and need some place to sleep." No. I told her, instead, about having walked from the Rockies and that I was on foot and how much a zoo the lake was. We were five minutes into our conversation before I brought up the question of public land. No, there wasn't any in the area, she told me. But, her son hiked the land anyways and knew a lot of good places to get out of sight of the public and the sheriff. Cain Lake was close by and although it was rimmed with expensive vacation homes, there were a few old roads that led back into the woods. It might be DNR watershed land, but it might also be private. Just don't let the homeowners see you back there, because they'll call the sheriff if they do. I bought a tall can of Steel Reserve from her for the night and spent another hour resting out front.

It was nearing dusk when I set out for Cain Lake, which was only a few minutes walk down the road. I passed many homes on the access road, some of which looked lived in, the others locked up tight, their owners in Seattle or Bellingham in their primary residence. Most people had come in from the lake and I lingered at the boat launch long enough to take a few photos in the late light. Laura had explicitly warned me not to try to sleep here as the sheriff regularly patrolled here since it was a favorite spot for teens to congregate. I located the road I was looked for and hopped the gates designed to keep out ATVs and other vehicles. I walked up in the growing darkness for five minutes and then dropped off the side for thirty feet to an area big enough to throw out my ground cloth and sleeping bag. It would be hard, but not impossible, to see me from the abandoned road. However, only someone looking for me would be able to spot me and I couldn't imagine anyone would take the trouble to do so.

I drank my can of beer in the silence of the woods, without a light, and thought about private property. My friend Lint said often that private property was theft. So had Lenin. I didn't think this was the case, but it certainly made life more difficult for those without it. I didn't have anything against people reserving a parcel of land for their own use, improving it, and maybe passing it along to their heirs. But when a person had to invade private property and break the law simply to obtain the basic necessities of life, such as shelter or water, then there was a problem. I didn't have a fix for the problem. I wasn't looking for one. I wanted a safe place to sleep tonight. That was all.

It was quiet and cool in the woods, but there was a thick humidity that made my skin damp whenever I moved through the air. I toted my gear up to the old road and had tea and breakfast there before starting the day's hike. I would make saltwater today at Samish Bay. It wouldn't be a long walk today, only 20 miles or so, for I couldn't make it to Anacortes without a great effort and there was a state park conveniently located for me to use as a bedroom. I snuck out of the woods and past the vacation homes to the main road and began the slog along the pavement, accompanied by speeding cars on their way to work, or where ever.

It took me an hour to reach the cross roads of Alger where a few homes were located, along with a very seedy looking establishment called the Alger Bar and Grill. It looked the sort of place where they have to mop up blood and sweep out teeth after every Saturday night. Had it been dark, I would have been afraid to go inside, or even walk through the parking lot. But it was light out and my run down appearance made it unlikely that anyone would bother themselves with me. Besides, I was hungry and the idea of an omelet was appealing. Inside the bar were many electronic slot machines, a few pool tables, and a strange assortment of locals eating breakfast, with only a few bottles of beer scattered here and there. I sat in a far corner to keep my smell from bothering anyone and started to enjoy myself. The place was much less ferocious inside than it appeared from the outside and the smiling, wise cracking waitress brought me the best omelet so far this summer. I suspected that they snuck a few extra eggs into it just for me. It came loaded with Cajun hot links, jalapenos, onions, and pepper jack cheese. And, even better, it was actually fluffy, yet at the same time dense, exactly as an omelet should be. After six thousand miles of hiking over the last few years, I've become an omelet expert, you see.

I spent an hour inside eating, drinking coffee, reading the newspaper, and watching the news on the giant flat screen TV. The hear wave passing through the region was supposed to jack the temperature up to 95 at Concrete, which is about where I'd be today if I had taken the PNT. It was going to be cool here, but there was a chance of a thunderstorm as well due to the convergence of hot air with the cold coming in. I set off down the road once more, my belly full, and quickly had to fend off several dogs who came charging out from a few houses. I really liked dogs, but now was starting to loathe them and their barking, snarling ways. I made a left at Colony Road, a small time, quiet pathway, and made my way underneath I-5.

On the other side by a hundred yards or so was a large house with a fence in front that held a sign telling me to Beware of Dog. On the other side of the fence was a small yap dog that metrosexual might put in his purse or crown with a tiara. Still, I walked out into the middle of the road just in case. At the far end of the fence, at the drive way, I noticed that there was no barrier. When I got there, a enormous Rottweiler with a massively spiked collar (like something from Mad Max) came charging out. The dog was serious and unlike most other dog encounters from the summer I was on the verge of a fight. I had a fraction of a second to decide how best to deal with the toothy dog that would be upon me in a moment. Dogs are individuals and there is no single right way to deal with an aggressive one. Some you tame with friendliness, others you glower at. Oddly enough, some part of me decided that the best way to deal with this 120 pound snarling monster was to attack it. It wasn't a rational decision. I did not weigh pro and con. I did not read some sort of sign in the dog. I did not think about it. And so I charged the Rottweiler. I wasn't trying to scare it. I was going to kill it with my hands.

I met George Drake five minutes after my encounter with the beast, which was still alive. The dog had stopped his charge when I charged him and we ended up a few feet from each other, locked into a standoff with both of us showing teeth. When I had shown genuine fight, the dog had reconsidered. It was off of its territory in the road and would have a fight with a much larger creature on its hands. It didn't back down, but it stopped. George grinned at my story. He didn't like dogs, but one had bought him the carbon fiber road bike he was one when I met him. Rather, the owner had to cough up $30,000 when his dog attacked George and caused an accident that put him in the hospital. When he saw me coming down the road he called out, "Are you walking across the country?", then slowed to a stop to talk. I didn't know quite what to make of the 73 year old man at first. I didn't know he was 73, of course, until he told me. I would have guessed 50. I told him where I had come from and he nodded his head, as if keeping time to a tune that was playing in his head. George understood what I was doing and why without my having to try to explain.

The man was a Korean War Veteran who had started a foundation to try to help Korean children who had been orphaned or abandoned during the course of the war. After creating and running the foundation he turned it over to others who could better manage it and embarked on a variety of adventures. He was originally from New Jersey but set out at 15 to hitchhike across America. 10,000 miles later he was hooked. A few years later he left home on a bicycle with a hundred dollars in his pocket and no plan in mind. He road to Mexico and then crossed Central America on foot and in chicken buses, finally landing in Panama where he got a job for the US Geodetic Survey and lived in a whorehouse. He did his stint in Korea and then moved to Colombia, where he spent a lot of time with the orphaned and poor of the country. This was a common theme in George's life: Live in poverty, know the people, then help them. His life wasn't about sitting in an ivory tower trying to figure out what the problems were that people faced. Instead, he shared the problems in a very direct and personal way. Then help.

George related story to me that crystalized who he was. He was teaching high school in Monterey one year and had a class full of students who were on the edge of dropping out. Not out just out of high school, but rather out of life. Bad home situations, little prospects, and no hope for the future. One night one of his students appeared at George's home and told him that he was running away. He just wanted to come and thank George for listening to him and talking with him, rather than talking to him, about life. When George asked him how much money the boy had he responded with, "Well, nothing really. Five bucks." "So, how are you going to eat? Do you know how to get food?" The boy was completely green and hadn't thought that far ahead. George convinced the boy to stay for a while longer and in exchange he would teach a class in how to run away from home. And so George taught a small class after hours at the high school on the mechanics and dangers of running away from home. How to get food. Where to sleep. How to avoid getting put out on the street by a pimp. As homework he even assigned them the task of practicing getting free meals out of restaurants by going around to the back. George taught them from experience, not from theory. He explained the very real dangers of being out without the protection of society or money and how to survive. None of the boys ran away.

George and I talked for an hour by the side of the road about travel and life and where I was going and what I would be doing when I got there. He was one of the most interesting people I had met this summer and had been one of the very few who was able to look past my appearance and not take me for a vagrant. I would have liked to have gone home with George to meet his wife and children and listen to more stories from his life. People like George are a treasure that no one ever seems to appreciate. They don't appreciate him because they don't know of him. People appreciate Dr. Phil because they see that fat bastard on television. Our society is twisted.

I watched George ride away in the opposite direction and I headed toward saltwater. I had only another thirty minutes to walk before I crested a hill and was able to look down through some trees and saw Samish Bay. It wasn't yet the Pacific, but it was close. I raised my arms into the air as if in victory and skipped down the road, drawing stares from a few househouders gardening in their yards. I still had a ways to go to actually get there, but the sight cheered me immensely.

Everything was just perfect this morning. I had had a nice sleep in the woods and the best breakfast of the trip. I had met an outstanding individual and been able to learn something from him by the side of the road. And now the sun was shining and I could see Puget Sound and even eat gumball sized blackberries that grew like weeds along the side of the road. The berries were everywhere. I would pick a handful and then stuff the entire mass into my mouth at once. My fingers quickly turned dark purple from the juice.

I crossed a set of railroad tracks and stopped to think about George once again. George wasn't an outdoor person and none of his adventures involved wilderness or wild places. George was far too interested in people and the societies they form to spend months in the middle of nowhere. But we shared many of the same values and appreciated many of the same things. Chief among them was purpose: We had both made conscious, active decisions about how to lead our lives. We were both active participants in our own lives, rather than spectators. This was a common theme with a lot of the people I had met this summer: None of us lived vicariously through other people.

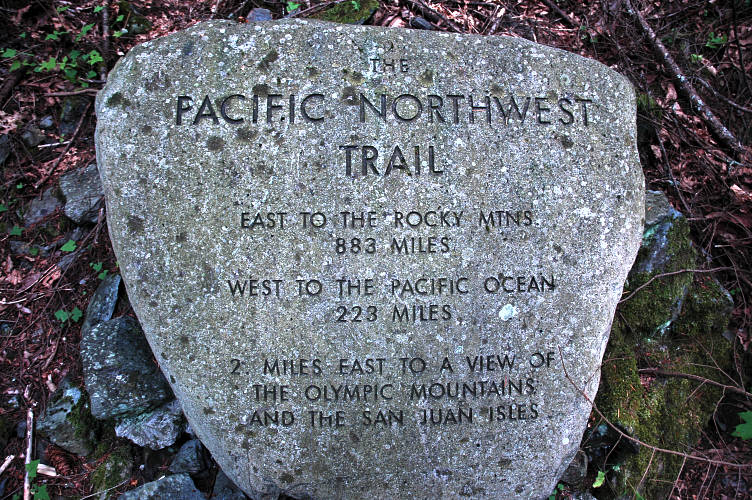

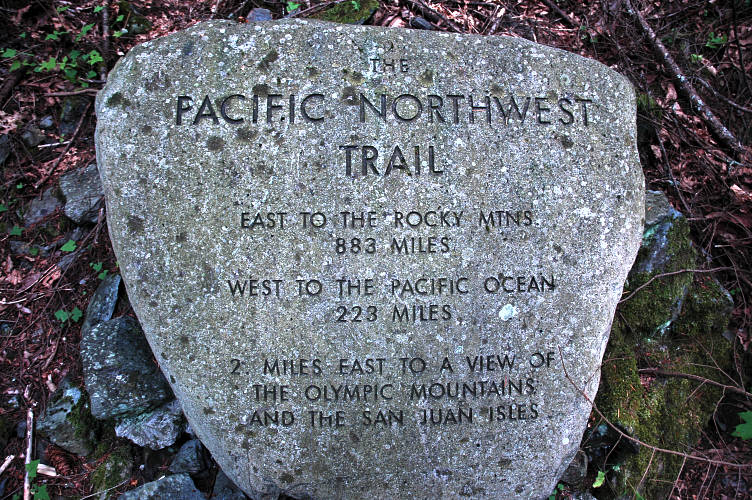

I hiked down to Chuckanut Drive, also called SR11, and decided to go a little out of my way to visit a trail sign for the PNT. This might seem silly, but I hadn't passed a single sign of the PNT and wanted at least one. I knew there was a big stone marker for the PNT about a mile up the road and wandered along the broad shoulder just to see it. The smell of the salt air, especially as it was low tide, was extremely pungent and almost burned my nose. It was strong, but healthy. Just before a fancy restaurant on the road there was a small cut trail. Above it was the rock and my only sign of the summer so far.

I took a seat at the rock and didn't feel very much. I hadn't been following the PNT too much of late and had cut off a large part of the trail that had been built explicitly for the PNT. The route through the Pasayten and North Cascades, for example, already existed before the PNT came into existence. The PNTA had focused its efforts on building a connecting trail from Puget Sound to the Cascades. I wasn't sure of the wisdom of this, especially given that their route went through lowland logging areas in a twisting, circuitous manner sure to appeal to dayhikers, but also certain to rise the ire of thruhikers. I took my picture of the rock and went down to the tide flats, which seemed much more interesting at the time.

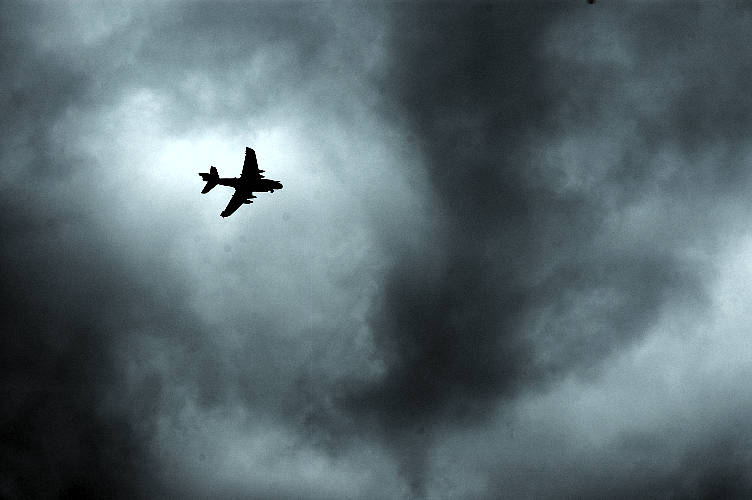

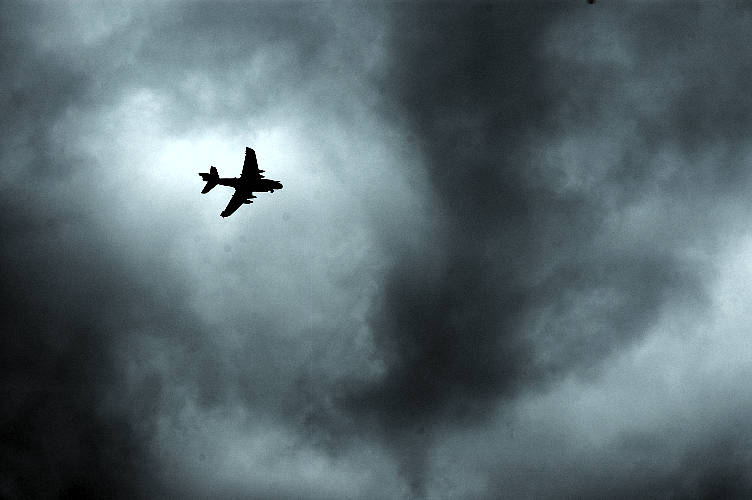

The guidebook gave the ridiculous advice of walking along the tideflats if it was lowtide. I tried it and sank into the gooey mess rather quickly. Instead, I hiked the along the railroad tracks and ate blackberries and smelled the saltair and gawked at the San Juan Islands and the storm that was coming straight at me from the water. It didn't seem especially important at the moment that I would be soaked to the skin in a little while unless I sought out shelter.

I crossed under the railroad trestle and continued past several No Trespassing signs to look at a long stretch of graffiti that graced the concrete eyesore. The artists who painted the murals knew what they were doing. This wasn't tagging or vandalism, but rather was a creation that took skill and talent and would enrich the lives of anyone who came down to see it. Since you had to break the law to see it I doubted that the people who most needed to see it ever would.

The mural had clearly been a communal effort, for the styles of the pieces were not the same. But every individual work blended nicely into those around it. I spent ten minutes looking at the various pieces. I couldn't read a lot of what was written, but one bit tucked away at the bottom edge of the mural was written in characters meant to be read by all. I read it and smiled. And then I read it again. And then I took a photo of it to make sure that I wouldn't forget it, especially when the days turned dark and the specters of boredom of routine and civil society and materialism and popular culture and seemed to be too great to ever overcome.

The storm hit me shortly after I left the mural beneath the railroad, but fortunately there was a fancy Japanese restaurant and garden center nearby and I was able to huddle under a door by the side, like a hobo, and waited it out. A few people looked at me, but that was it. No one seemed to care that I was there, nor did they seem to think me odd or out of place. The rain lasted for ten minutes and then passed on to the mountains. I emerged from the safety of the door way and continued my walk down the road, now listening to a kitchen radio program whose self proclaimed "foodies" were extolling the virtues of the humble mortar and pestle.

The walk through the misty remains of the storm, passing along the edge of the bay, was pleasant in the sort of moody way that seems to characterize much of the Pacific Northwest. I passed through Edison Station, which was a hamlet only large enough to have a postoffice, tourist cafe, and a junk store. Unfortunately the only convenience store in town was closed. I was able to get some water from outside the PO, stopping only long enough to convince myself that I didn't want to eat in the cafe.

Not far down the road was the town of Edison itself, which, like many places I had visited during the summer, was struggling for its soul. Tourism provided most of the revenue for the town, but that was also a cancer that was eating away at the core. It was a hard balancing act for most places, but Edison seemed to be coping as well as any others than I had seen.

I wandered into town and spied a cafe that seemed to have no tourists at it. Indeed, it was the sort of place that tourists try to avoid. No kitsch. No gimmicks. No parking. A sign on the door said it was cash only: No credit cards. I dropped my pack outside at a table just as a group of cyclists pull up, each towing a substantial trailer. One looked like he had a coffin behind him. Inside I found that I only had $4, but that was enough for a coffee. On the off chance that the sign was wrong, I asked the waitress about credit cards. "Sure we take them", she said. "We just haven't taken the sign down yet." I smiled at the sheer laziness of this. Definitely not a tourist joint. I ordered a bacon cheeseburger and inquired about a store in the area. Any place to buy a six pack? Unfortunately not. There were only tourist bars into town, but no stores where you could buy beer to go. I explain where I had come from and I saw a woman in back, the cook and owner, perk up her ears.

I sat outside at the table and talked to the cyclists. They were a band from Portland who were spending the summer cycling from Vancouver, BC to San Diego, CA and were playing gigs along the way. The coffin was actually a double bass! The waitress came out with my cheeseburger and told me that the owner was calling around seeing if she could rustle me up some beers. I ate and talked to the cyclists. Just as I finished, a seventy year old man on an ATV roared up to the cafe and shouted, "Who ordered the beers?". He put two cans of Bud Lite into my hands and then sped off. The cyclists and other onlookers broke out in laughter.

The waitress had been wrong, though, about not being able to buy beer to go in town. After filling my belly I hiked through tourist row, stopping at a gaudy bar filled with fat, pink tourists who seemed pleased with themselves for having a beer at 3 pm. I got cash out of the ATM and declined the offer of a beer from a pretty waitress. Next door was a fancy grocery store selling expensive cheeses and various crackers from Sweden. Inside, tucked away in a corner, were a few forgotten bottles of beer. I bought a Hennepin and a La Fin du Monde for later and headed out for Bay View State Park.

Edison, it seemed, had been founded as a sea port for the fishing industry. Now there were a few farmers who worked the fertile soil and a lot of wealthy retirees and vacationers. The contrast between wealth and the past, the working, hardliving, struggling past, was tremendous. Three thousand square foot homes with a modern pleasure yacht parked out front were only a stone's throw from rusted out hulks of fishing boats that seen a hard life. The workers were mostly gone, except for the farmers perhaps. In their place were people who cruised to Seattle to drink $20 martinis in a boat bigger than my apartment.

I left town and strolled along side fields growing various cash crops, or holding feeding pens for fleecy animals. I turned my radio on and enjoyed the pastoral scenery, which was much more appealing than the symbols of excess wealth that were on display in parts of Edison. Who was I to talk about excess wealth anyways. I wasn't a good judge, it seemed to me. I thought I was wealthy because I had two bottles of high-end beer in my pack and would be able to sleep on public land tonight instead of hiding in the woods from the sheriff. I put questions of social justice out of my head and just enjoyed the walk.

I crossed the flat lands and climbed a short hill to a plateau that ran above the water with plentiful views of the oil processing plants across the bay near Anacortes. There was supposed to be a trail along the water that took me off the roads, but I couldn't find it. In truth, I didn't look very hard because the road was plenty scenic and there were only a few cars. There were houses out here, but they looked as if people who worked for a living resided in them. A few of said workers smiled and said hello to me as I passed their houses, curious as to what I was doing.

It took nearly two hours to get to the state park, which I found, to my horror, filled with RVs and trailer campers. It wasn't the cute place I had imagined it to be and was instead a sort of feed lot for people with vehicles who couldn't be bothered to sleep on the ground. I wandered around for a while and found a place that looked like it was meant for people without a thirty foot vehicle. I had hoped to be able to skip out on paying $20 for the privilege of sleeping on the ground, but I knew someone would find me eventually.

A man in a golf cart eventually came by and told me in no uncertain terms that I couldn't stay for free just because I was on foot. Yes, even people without vehicles have to pay. He wasn't the ranger, though, he was only a volunteer for the park and was coming around to make sure everyone had paid their fee and was in the right place. He was actually a nice guy and told me these things as pleasantly as possible. I wandered down to the ranger and negotiated a lower price. Only $14 to spend the night. I should have argued that I had no money and couldn't pay anything. But I wanted to drink my beer and relax and not worry about some irate landowner finding me camped on their land. It was going to rain tonight and it was a lot harder to hit with the tarp up than it was to stealth with only my sleeping bag. I paid the man and returned to my camp to drink my beer. This wasn't any ordinary beer, but rather the good stuff that humans spend time and effort to make. Steel Reserve, the bad stuff, is made by robots and contains 40% antifreeze. It is so good that it is banned from poor neighborhoods in Tacoma where its price of $1 for a 24 ounce can is apparently too low for the health of society. I drank my beer and thought about the concept of wealth and what made a person wealthy. I was the wealthiest person I could think of, except for maybe George. I was looking forward to tomorrow and had the freedom to mould tomorrow into any form I wanted it to take. That's wealth.

Drinking a liter and a half of 9% beer before bed does not encourage an early start. It rained on and off during the night and I awoke to a mist that hung on everything, wetting my beard and clothes as I moved about to get ready to depart. The streets were empty, except for a few residents out for some morning exercise. I picked up the Padilla Bay Shore Trail at a state park of the same name. The trail was more of a bike path around a sequence of dikes, but it was extremely scenic, had plenty of interpretive signs, and lots of benches to encourage people to linger.

The state park itself was small, with agricultural lands running up right against it. The land was extremely rich and productive, but the opportunity to create a polluted mess was also high. The farms would bleed directly into the Bay and clog up the rivers that salmon needed. Unless care was taken, the agriculture would have a negative net effect. Many of the interpretive signs were about the clean up efforts that had been taking place and the restoration projects that had been undertaken by the city, county, and state.

The rain that had come through overnight had moved on to the mountains, where it would have battered me had I taken the official PNT route through the logging lands south of Mount Baker. Baker itself was easily visible on the horizon and the sight of it drew my mind to coming back with a tripod and taking early morning and sunset photos:The light and the contrast between the farms, the water, and the icy volcano would be a good one.

A few joggers passed me as I strolled along the shore trail, but I mostly had the place to myself. The trail was, unfortunately, only a few miles long and I soon found myself wandering along a paved road by some industrial buildings and large farms that were in the process of being harvested. After the idyll of the shore, the industrial park was a bit jolting. But the jolt was really just a way of the day to warm me up for what was to come.

The road dumped me onto SR20, which I had met several times before during the summer. The highway is one of the major commuting arteries in the region as it connects several of the islands in the Sound with mainland. Due to private property and the constraints of geography, there was nowhere to put a trail and thus the PNT was routed onto the highway shoulder. I stopped at a drive through coffee shack and got a 20 oz, four shot Americano for the roadwalk. With my radio blasting in my ear and the caffeine making me giddy, I set out down the highway, waving at the commuters on their way to wherever.

I was actually happy on the walk, although it wasn't clear to me if it was because of the coffee or because of the novelty of the walk. It was actually entertaining to walk along the road and smile at the commuters. I had a distinct Huck Finn feeling to the walk. I crossed a large bridge over a channel of water and with it left the mainland for Fidalgo Island, the site of some of the more ridiculous sections of the PNT, which I'll get to in just a moment.

I was out of coffee and so after the bridge I picked up another cup of the black stuff from another coffee shack. I sat in the parking lot resting, looking as much like a hobo as possible, except for my shoes and pack and camera and trekking poles and other expensive gear I was toting around. Although it was August, the skies overhead were iron grey and the landscape had the moodiness that makes the Pacific Northwest so charming for visitors. I've actually come to like the vibe, but not for the whole of the eight month winter that we suffer from.

A long spit of land juts out into the Sound and separates Padilla Bay from Fidalgo Bay. This spit of land, March Point, houses an industrial wasteland of oil refineries and other heavy industry. I had taken photos of the industrial area from the Padilla Bay side. Rather than take a direct route, perhaps two miles long, the PNT is routed directly around the perimeter of the wasteland. I chose the direct route along SR20.

My route eventually detoured off of SR20 and onto smaller roads that saw less traffic, but also that had no shoulder. As annoying as the traffic of SR20 was, it was actually safe to walk it: The shoulder was enormous and a driver would have to veer far off route to clip you. The smaller road had no shoulder, was twisty, and it wouldn't take a lot for a driver to put me in the Anacortes hospital. The route was scenic, however, running north along Fidalgo Bay. I passed an RV park, at which I wanted to vomit from the sight of so many hulking beasts, each a symbol of the materialism that has grown so out of control and is rotting our country. It was a recommended stop in the PNT guidebook.

The silliness of the PNT route around March Point was equaled by its recommendations for Anacortes. The route takes you to the outskirts of town and then immediately outside of it: You hit the least charming part of town and never get an idea of what the place is like. Besides, most PNT hikers have been hiking for a long time and might actually want to stay in town, drink a beer or ten, and eat a gallon of icecream with their Super Giant pizza. I made a right instead of a left and headed for the downtown district. On the outskirts of Anacortes was a place without much of a soul, much like the outskirts of every other city in America. As I drew nearer to the downtown district things began to change. The houses got nicer, the businesses more interesting, the people smiled more. At the core of downtown was a large archway, on the other side of which chain businesses seemed to be banned: Only small, local establishments were allowed. After stopping in one charming motel, I went to another that they recommended as being a bit cheaper. This was how I found the San Juan Motel.

A room with tax cost me $76. I didn't care and rationalized the expense with a simple: This is why I have a job, this is the only reason I have a job. I was even going to spend tomorrow here as well. I was tired from the long traverse from Oroville, more than 250 miles in the past for me. I want to eat and drink and nap and watch movies and talk to locals and spend time. I've only got so much of it. I fell into town mode quickly. I bought some beer and snacks at the grocery store, then scrubbed myself clean while drinking beer in the shower. When you're as dirty as I was, it takes multiple washings, and several cakes of soap, to get the job done.

Time passes differently in a strange town after a long time in the wilds. I lounged on the soft chairs in the room. I spread out on the squishy bed. I stood on the balcony in the misty air, barefooted and without a shirt, drinking a beer, for the sheer luxury of it. I soaked and washed clothes and hung them up to dry. I put on a clean shirt that was sitting in my bounce bucket at the PO and went out in a fine drizzle to the Rock Fish Grill, which is the front restaurant for the Anacortes Brewing Company. I polished off a large helping of fish and chips and swilled several pints of excellent PNW IPA while making small talk with the women behind the bar. I had come a long way since Oroville, not just in terms of distance but, more importantly, in terms of culture. Oroville, and really the whole region in between the Cascade and Rocky mountain ranges, was vastly different than it was here on the coast. Places like Oroville, Republic, Metaline Fallls, Eureka, these places had an authenticity to them that was hard to ignore. Life was still agrarian in nature and the culture was homogeneous, which made understanding people simpler and attitudes more direct. I liked them. Anacortes a lot. For completely different reasons I was liking Anacortes as well. I felt at home here and the weather, the mood, the touch of the place was something that was comfortable for me. Even the rain and the dreariness. I stumbled back to the San Juan after making the requisite stop at the grocery store for ice cream and beer, and took my ease on the soft bed to watch television and gorge myself just a bit more. My wealth was overflowing.

I fell asleep with the light on and the television flickering. An empty tub of ice cream and several bottles of beer littered the table next to the bed. I was on hiker time, which means that sleeping in was until 7:30. I showered, dressed, and headed out into the misty air in search of breakfast. My day was full of things to do and not much time to do them in. I needed to eat breakfast, drink coffee, and read the newspaper. That would take two hours. I needed to buy and write post cards for people at home and abroad. I needed to call my mother. My tour of Anacortes would cost me another hour of my life, though I could use it to scope out the lunch and dinner options in town. Afternoon beer and a subsequent nap must be had, as well as a trip to the post office, the grocery store for ice cream, and at some point I needed to find a tide chart. I wanted to finish reading Xenophon as well. I was going to be a busy day indeed.

I managed to accomplish everything that I had planned out and was so pleased with myself that I spent an extra hour at the Brown Lantern eating carnitas and drinking IPA for dinner. For a moment during dinner I remembered that I needed to start thinking about permits for Olympic National Park, but quickly concluded that the park administration can go to hell and I'd just show up and hope for the best. Besides, getting a permit seemed a lot like work and I had enough of that to do. After all, I still needed to go to the grocery store for another pint of Ben and Jerry's and some more beer. Plus there was television to watch. I didn't want to repeat my busy day every day, but in the context of a thousand mile walk, it was sublime.

Today I meant business. I was leaving town and heading south through Fidalgo Island and onto Whidbey Island, where I meant to track down a brew pub in the town of Oak Harbor. I'd never been there before, but there was rumored to be free camping in town and the location of the town, right on the water, made me sanguine for its prospects. That just means that I thought it would be a nice place to spend an evening. I ate a big plate of chorizo and eggs, drank a half gallon of coffee, and read the paper at the Island Cafe to fortify myself for the walk. The PNT route again didn't make a lot of sense to me and I had plotted out a route that would take me around the coastline for a while. Even though I'd be on roads, I justified this with the fact that the PNT was also on roads, except for a mile here and there. I bought a four shot Americano for the walk and set out through the western part of Anacortes, heading toward the ferry.

Anacortes was a place I could move to. The houses were well maintained and had been built mostly before the post-war boom in ugliness took hold of America's cities. I didn't have the money to buy a place here, nor was there an institution that would let me teach, but I thought the town a fine one, even in the drizzle that fell occasionally. People smiled and said hello to me as I passed them on the street. In Lakewood people frown and glower at you if you look them in the eye or try to do something as offensive as smiling at them. You might be a child rapist, after all.

My route through town took advantage of smaller streets, but eventually they funneled me on to the main arterial road running to the ferry. Even here, though, the town was pleasant. There were no strip malls. There were no teriyaki joints or pay day loan places or rent-to-own stores that so blight my home. I passed a home that looked just like a castle, complete with a turret. It didn't seem garish or out of place: Someone a hundred years ago had wanted a home that looked regal and so had built it. I thought about going up and asking to see the inside, but thought that might be pressing my luck.

A man in a beat yellow compact car from the 1980s, drove past in the opposite direction, did a U-turn, and pulled up along side me to see if I needed a ride to the ferry. It was raining lightly and he thought I might want to get out of the wet. I thanked him and told him I was heading to Oak Harbor on foot. He seemed to understand. Another U-turn and he was off. I continued toward the ferry, rather pleased with myself. If I was smarter than I am I would have taken the ride to the ferry, gotten on it, and explored the the San Juan Islands. I knew a woman that lived on Orcas and could track her down without too much difficulty. There was also a restaurant there that I wanted to visit and I was sure there would be brewpubs a plenty, along with some free camping and interesting people. But I'm not especially clever and resolutely stuck to my plan of Oak Harbor.

The views of the Sound and the islands were enhanced by the mist and the clouds and the drizzle. It was like winter today, even though it was solidly August. Florida would be uglified by the weather here, but the Pacific Northwest is somehow enhanced by it.

Every place is, to some extent, shaped and moulded by the weather it experiences and the physical environment that it sits in. Chicago has cold weather and lake effect snow, but those don't shape it: You cover up for a few months and curse the blasting wind, but then April shows up and life is good. Atlanta is hot most of the year and disgusting all of the year, but that is more a function of the amount of concrete that the city has poured than the weather. Houston is the fattest city in the fattest country in the world, and this is due partly to the extreme heat and humidity there. The PNW is defined by mist and green things, rain and water and dynamic clouds. It shapes the people who live here, the kinds of homes we build, our activities and food and drink. There is a reason that grunge, or so-called alternative music, came out of the PNW and not, say, New York City.

I made a left on Anarco Road and started through a small subdivision that looked thoroughly planned and completely devoid of a soul. It didn't last for long, fortunately. I passed through some deep woods and then out onto a farm lined country road where people with interests clearly lived. You don't make your own art and not have an interest.

After a few hours I intersected SR20 was forced onto its now narrow shoulder. Although it was Wednesday, the road was packed with cars heading to Deception Pass. The pass itself was quite pleasant, though there were far too many people to make it enjoyable for me. The pass refers to a narrow gap between Fidalgo and Whidbey Island that gives boats access to Puget Sound, rather than a mountain pass, though the function is the same.

On the other side of the bridge I found a packed parking lot with people milling about. I wanted to rest, but found myself the object of too much attention and so headed down a trail through the woods toward the water. Unfortunately the number of people only increased. It wasn't the old couple that got to me. It wasn't the solitary beach walker that irked me. It was the gawking family of six with their stares that got under my skin. I didn't know why my sense of calm had vanished so much, but the stares from the children and parents, and then their attempt to cover up their stare, just burrowed deep with in me. They were not sure what to make of me and a bit scared. But kids are curious, especially when young, and curiosity can overcome fear some times. The kids didn't know enough, or hadn't been told, that they should be afraid of a homeless person. But the adults thought that this was the case. At the same time, they probably realized that I wasn't truly homeless: I just looked like I was.

I walked quickly along the beach, hoping to get away from the families. My hope was let down, however, by yet more families at West Beach. I bought another Americano from a concession stand, where the girl behind the counter was studying a calculus text. I probably should have said something, but I just wanted to get away from the families and their stares. The jets from the Naval Air Station were practicing some sort of landing run and would repeatedly drop down, approach a run way, then swoop up, circle around, and do it all over again. The air was in a constant state of loud.

The families were gone and it was only myself and few retirees on the beach. If my ears had not been constantly ringing from the sounds of the jet engines I might have enjoyed the walk along the water from. Walking along water normally is peaceful and soothing for me, especially when the water is salty and I can look out toward Asia. Instead I hustled. Masses of private property signs began to appear as I neared the landing strips for the air station. The law made the beach public property, but I was confined to it and couldn't venture onto the grass, where the walking was easier than the soft sand, for fear of drawing someone's ire. I strolled along as best as I could, but finally could take no more of the buzzing jets and cut through the yards of a few vacation homes and onto a gravel road where a developer had marked off lots for more luxury homes.

I walked down the road and waved at a man doing some yard work in front of posh home. He seemed a bit surprised to see me and we chatted a bit in passing. I walked down the road and found myself hemmed in by a gate: I was inside a gated community. The gate was surrounded by thorny bushes, so I couldn't go around it and had to climb the gate and hop over the other side just to escape from it. I turned on my radio for the walk to SR20, which I found to be just as busy, but with a broader shoulder, than it was when I left it. I wasn't in an especially good mood, and it just got worse when a steady, hard, cold rain began falling. Cars and trucks raced by at 60 miles per hour, splashing and misting me as they went. I took shelter from the rain in a little open faced hut on someone's driveway where presumably their children waited for the school bus. There was no one around and I hoped the owners would not come back until the rain stopped. I sat and shivered in the little lean-to, cramped and cold and generally in a foul mood. I felt sorry for myself.

I stayed for thirty minutes in the shelter before the rain slowed and I felt like walking again. The image of Oak Harbor and its brew pub kept me going, for I imagined it would be quite a bit like Anacortes. The county bus pulled along side me and the driver asked me if I wanted a ride. I told him that I was fine on foot, to which he responded "Really? Its free, man.". I kept moving on foot and was happy when the rain ceased completely and I started to near the outskirts of town.

My dreams of what Oak Harbor would be like were quickly fading. Traffic from the base was intense. Stores on the outskirts were mostly chains. Homes were in disrepair. There were teriyaki joints, pay day loan stores, and rent-to-own outfits in the strip malls, which seemed to be everywhere. I followed my nose toward the downtown area, passing shifty looking people loitering outside of convenience stores and schools with trash floating through the playgrounds. I was recognizing home. Lakewood looked like this. So did Bremerton. So did Silverdale. So did Tillicum. It was the military presence. I saw people arguing in the street and angry voices coming from cars. People looked afraid and tense. The downtown area didn't get any better. The town was trying to make it nice and had kept the strip malls out along with the chains that soiled the outskirts. But many businesses were simply closed. I looked in a couple of bars and saw only sad, bored drunks. I looked around for the brewpub but couldn't find it quickly and so hurried on.

On the other side of downtown I spied a large open area that seemed to be the city park and RV campground that I was looking for. It was along the bay and seemed like it would do for the night. As I got closer, though, things looked less good. People were living in their cars there, and the cars didn't look like they were capable of moving. There was a cost to camp here, but I didn't want to pay $10 to sleep on some grass next to a car dealership. I put up my tarp and arranged my bedding. I took anything of value with me to explore around town.

I walked around the park for a little while and noticed the same sort of people I see loitering around Lakewood. Frowned faced, shifty, and trying for all the world to scare you away from them, these people, those people, normally are not a problem: They just pretend to be. But I was starting to get the impression that there were a lot of broken lives in Oak Harbor and I was going to spend the night in the heart of the dumping ground for those lives. I saw a few homeless people hanging out in the picnic lean-tos, but they seemed fairly non-threatening: They just wanted to disappear from sight and be able to sleep safely in a dry place for the night.

I walked into a different part of town looking for a place to eat some dinner and found only more depression. Blighted liquor stores. Pulltab joints. Groups of ghetto-styled youths arguing and yelling. I wandered through strip mall after strip mall, confident that my appearance actually was working in my benefit. I strolled through one parking lot to another until I found an inviting looking place called 1-2-3 Thai. My plate of Paht See Yiew was pretty respectable and it gave me a chance to hide from the ugliness outside. Next door was a Safeway where I bought some ice cream and two tall cans of Steel Reserve with which I could continue to hide from the ugliness of town. It was raining when I came out of the store and so I sat on a bench under cover of the store entryway and waited and felt sorry for myself once again. A man started up a conversation with me and offered me a ride somewhere. I snarled and left for the safety of my tarp and the comfort that the alcohol in the beer would bring me.

I sat under my tarp and drank beer and wrote in my journal. Oak Harbor had been a dream in my head for much of the trip, but the reality turned out to be a nightmare. I would have been better off sticking to the PNT route along the water instead of coming into town and seeing the depression that was the town. Oak Harbor could be very good and it was clear that the city was trying. But it was fighting a losing battle and the military base would always triumph. I saw shadows moving in the black air of night and my imagination began to take hold of me. I thought about taking down my tarp and moving on to anywhere else. Anywhere was better than here. I fell asleep with my knife in my hand.

I woke up with my knife in my hand, still in its sheath. I needed no motivation to get going in the morning and was quickly packed up and moving across the field, cutting cross country to avoid the camp host who might want $12 for the night. The town was quiet and still and seemed much less threatening than yesterday. I got an Americano from a drive through and walked down the main road through town, heading toward SR20. I dodged over on Scenic Heights road since it looked like it followed the bay and would provide for good views and little traffic. Whereas Oak Harbor was trashy, the neighborhood that walked through on the road was strictly petite bourgeois. This is where the super heavy duty diesel pickup trucks that have Get 'er dun bumper stickers are parked when they are not being driven to the grocery store or to pick up the kids from school. Not slummy, just low brow, but in a way that the occupants get to pretend to have class.

I made it through the extensive sub division without incident and entered the country side, where living was once again pleasant and I didn't have to worry myself with my snobbery. NPR came in fine and I enjoyed the morning walk through the hay fields and farms. I was even passed by more people out walking, running, or cycling than I was by motorized vehicles.

My route was taking me around Penn Cove and was very lightly developed. Quiet, serene, peaceful. Oak Harbor, it seemed, was something of an isolated blight. A localized tumor. A cyst on the back of Whidbey Island that maybe some day would fade away all on its own. The problem with diseases is, though, that they normally require some tough love to get rid of.

My road intersected SR20 once again, but the shoulder was wide and the blackberries were fat, juicy, and abundant. I wondered what people thought of me as I stuffed handful after handful into my mouth, chewing sloppily as I picked the next batch. Fortunately a small road, Madrona Way, diverged from the main path and allowed me some more quiet time along the road.

True to its name, the road was littered with Madrona Trees, which have always made me curious since I first started coming out West. The bark of the tree looks like it is painted on, almost like a thick terracotta. The bark eventually peels and it looks like, well, peeling paint. When I first saw the strange trees at Stanford in 2000, I was completely and utterly amazed by them and spent a lot of time trying to figure out why anyone would paint the trees such a strange and interesting color. California certainly was bizarre!

I rumbled down the road and enjoyed the views when I could, listening to NPR the whole way through. B&Bs were scattered about, with each of them having some sort of marine theme to them. Captain Jack's. The Admiralty. Oyster Bay. The road ran up above some, oddly enough, oyster beds and along to the city limits of Coupeville. The woman who had given me a lift to Whatcom Lake lived here, but I didn't even know her name let alone where she lived.

The town itself, after passing through a small residential section, was really pretty charming. The downtown water front area was pretty clearly geared toward tourists, but in a tasteful sort of way. There was a nicely restored pier area that I walked out along into the water to get a better view of the bay and the town.

There wasn't much action going on in the town itself as it was only 11 am, which is far too early for tourists to show up. I was able to linger on the pier and enjoy the smell of the salt air without having to bear the gaze of curious families unsure of whether or not I would try panhandle them or maybe chop them into little bits with an axe. There was some nice local art work that I rather appreciated.

I also appreciated the fact that there was a mention of the PNT on a local map. This was only the second real indicator that I had had this summer that there was such a thing as the PNT.

I was feeling a bit hungry and decided to indulge myself by taking an early lunch at a promising looking joint called Toby's. From the outside it looked like a musty, old, run down dive-ish place. I couldn't see inside because the only window was plastered in stickers and was too old and smoked to see inside anyways. Just my place. There were a few old-ish men sitting around drinking pints, including several people whose uniforms made them as employees of the federal government and of the city. Yup, my place.

I came out of Toby's feeling greatly refreshed, not that I was hurting before I went in. I had a pint of Guinness, or maybe it was three, with my bacon double cheeseburger. If I didn't have a brewpub to get to I would have hung out in Coupeville just to see what would happen at Toby's in the evening. I didn't really have anywhere to sleep, but something would have come up. Still, I had not one but two brewpubs waiting for me in Port Townsend and I had to get a move on if I wanted to see them both.

I picked up another cup of coffee for the walk to Port Townsend, which I thought was maybe five miles down the road. The PNT route along the beach would have been more scenic, but walking on squishy sand isn't much fun. The views along my route were pastoral and peaceful, rather than stunning. But I was happy from the beer and the food and there was little that could happen to spoil my mood. Urban hiking sure is hard.

The weather couldn't quite make up its mind to rain on me and I had a nice cloud cover to keep me nice and cool for the walk to the ferry. Old people working in their gardens waved to me as I went by. Several cyclists towing trailers behind them passed, with two Australians even stopping to ask me if this was the way to the ferry.

That's right, a ferry. The PNT is the only trail I can think of where you have to take a ferry across a large body of water as part of the route. The AT has a river ford in Maine downstream of a dam and, for safety's sake, the ATC asks that you use a ferryman that they engage for the summer. If I ever get that far I'll just walk across and hope that the dam doesn't decide to release a big water flow on me. Anyhow, my route ended at Fort Casey on Whidbey Island and Port Townsend was across the water on the spit of land called the Quimper Peninsula, which itself was part of the Olympic Peninsula. The line up for the ferry was deep, and cars were already parked waiting for the next sailing. I paid my $2.60 and walked aboard. For once it was faster to be on foot.

I wandered up to the top deck of the ship and had a look around before we departed. Although the car portion of the ferry was full, there was plenty of space for humans to walk around and not feel cramped: Good views could be had by all. The crowd was a mixture of locals commuting to or from the mainland, tourists making a drive around the Olympics, cyclists, and a few people on foot, like me.

As the ferry smoothly made its way out into the Sound, I was able to look back and see where the PNT ran. I was, to some extent, a bit regretful that I had taken the more inland route that I had, even though it had been quite enjoyable. The beach walk, I told myself, might be scenic, but the footing would be terrible and the sand would get everywhere. I saw people wandering around the beaches and I couldn't quite convince myself.

The ferry ride was not long, perhaps 20 minutes, and we were soon approaching the water front of Port Townsend, complete with a fine plume from a power plant rising nearby. The water front was indecisive: It clearly wasn't run down and slummy, but it neither did it look fancified and touristy. And, gasp, it looked like people actually lived there. I didn't think a town as well located at Port Townsend could have escaped the scourge of development, but perhaps it had.

I satisfied myself with taking photographs as I went, which was a bit easier for me to do as there was some sort of professional on board and all I had to do was follow her around and point my camera at what she pointed her camera at. You see, photography now has almost nothing to do with technical skill.

With the advent of modern computing, camera have gotten good enough to meter (measure the light) of a scene very accurately, autofocus is nearly flawless (except to people who look at photos under 100% magnification), color rendition is punchy and saturated, and digital allows every common slob (like me) to take lots of photos and get instant feedback.

And so the technical aspect of photography, at least with SLR cameras, has been reduced to something Galen Rowell once said: "Try f/8 and be there.". All he meant was that the important bit of photography was being in the right place at the right time and pointing your camera at the right thing. That was exactly what I was doing with the professional, only no such person really existed. I just needed an excuse to launch into one of my favorite sermons and to fill up some space between pictures that I rather like but have no real reason to be shown, except for vanity's sake.

I got off the ferry with the other passengers and wandered into town. I didn't exactly know where I was going, but most people seemed to head to the right, and being a good herd member I followed. I still couldn't quite make up my mind about Port Townsend, however. Although the streets brimmed with tourists, there were no chain stores around to take there money. But there were stores with the sort of junk that tourists want to buy: They were just small, independent operations. I walked down the street, carefully avoiding the others, and came to the first place I was looking for: Waterstreet Brewing.

I went inside and liked the place immediately. Warm, old wood framed. Brass rails. No tourists. A few happy, local drunks. It was only me and a few others in the bar area, though families floated in and out, passing through the bar area on the way to the safe area roped off for them. The bar tender poured me a tall, cold pint of a single hop beer called Strange Brew. Nowhere else in the world is such consistently fine beer made as in the Pacific Northwest. The brew exploded in my nose before I ever took a sip of it. Hops, hops, and more hops in the nose. They tickled my throat. I took a sip and smiled.

I finished the pint and had another of the same, savoring as much as I could. The beer was strong and I slowed my pace as I felt the first pint hit me hard. A old man walked in and sauntered up to the bar."Hey there, beautiful. How much for a shot of Jager?". The bartender walked over to the man and told him a shot was $7. "Gimme two of those bad boys.". Now, Jagermeister is the drink preferred by young ski bums and soldiers on the deficient side of intelligent, or rah-rah fratty boys out to do some whoring and raping, but this man was easily in his late 50s and didn't look like he had an Abercrombie shirt in his wardrobe at home. She poured out two drinks and he put them away in a single gulp. "I'll have another two, sweetie pie." She poured out two more and he repeated his routine. He slapped a couple of bills on the bar and walked out.

She could see that I was a little amused at what had happened. "He does that every afternoon about this time. Always makes sure to ask how much they are, too" she said with a grin. I returned to my beer, smiling myself. I put away another two pints of beer and paid up. The bartender must have liked me because the pints didn't cost a whole lot. Maybe it was happy hour. I rolled out into the streets and started thinking about where to spend the night. My guidebook said that there was camping at Fort Worden state park, and it looked pretty close. As I walked though town in its general direction I saw the Tribe.

I was wondering if I'd see them here. These 14-24 year olds show up in places like Portland and Olympia and Seattle and Bellingham and Vancouver. Homeless (except when staying in a hostel, which is most of the time), dreadlocked, and bearded (men and women, too). Frequently they are carrying musical instruments, fibercraft bags, and ascribe to an odd mixture of anarchism, paganism, trustafarianism, and class warfare. They seem to exist simply to annoy other people, especially any one they think is "bourgeois". I watched as they picked arguments with people in cars, people on the street, people who were trying their best to ignore the Tribe seemed to get it the worst. It was as if they really wanted someone to pay attention to them and when they didn't get that attention, they acted out. Just like a 8 year old might.

I left the Tribe as they did their best to irritate others and shock them out of their middle class complacency. Maybe that was just what they thought they were doing to justify themselves. On my way out of the downtown area, I saw one coming my way. Young, blond, beard, dreadlocks, fisherman's pants, piercings, guitar strapped to back. I smiled and said hi as we passed. He snarled and for a moment I thought he might stab me in the eye.

The walk to Fort Worden turned out to be much longer than expected, which was shame because I knew I would just have to walk back into town to get some dinner, beer, and ice cream. The park was a forty five minute walk from the main area, though I noticed that there was a bus stop right next to it. The park was large and it wasn't clear where to go, but after wandering around without being able to find anyone who knew anything, and not wanting to camp with the families in the RVs again, I found a hiker-biker site, which was nothing more than a clearing in some woods with a couple of picnic benches thrown in. Still, it was out of sight of others, flat, and clean. Two tents were set up and clearly hadn't moved for a while.

I set up my gear and wandered back into town because the bus ran only once per hour and it was faster to walk than to wait and ride. At least there were plentiful blackberries along the route. When I got into town I ate dinner at another 1-2-3 Thai place , where I watched members of the Tribe trying to hitch hike out of town. When a car would approach they would wave their hands frantically and do a little dance. When a car passed them, they'd shake their fists and rage about it. I shook my head and ate my food.

Outside of the Safeway I met a nice old man with a thick grey beard and a friendly dog. The man was holding a sign asking for change. Business didn't seem too bad and I thought the dog probably helped. It also helped that the man was actually nice, rather than mad at the world. We only talked long enough to exchange pleasantries and then I left to buy supplies for the trip to Forks, on the other side of the Olympic mountains, along with beer and ice cream. I ended up walking back to Fort Worden rather than waiting for the bus, which was certainly more exercise than I wanted to get.

Back in camp I sorted and re-packaged my food and drank beer. Another ratty tent had appeared since I was gone, though I hadn't met the owner of it. I was pretty sure that the park would want money to camp here, but I was also sure that none of us had paid for the privilege to sleep here. No one would camp here unless they were without a car, and if you were without a car you probably were homeless also. The night got dark and, done with my chores, I relaxed on the picnic bench and thought about the Tribe and the old man and the difference between the two. They were both ostensibly homeless, but that was about the only similarity. I was also homeless, but at the same time not homeless. The people in the Oak Harbor RV were homeless, but also different. I liked the old man the best. And why? Because he was nice. He was friendly. He didn't make me afraid and he smiled a lot.

I drank the good beer first and then took to the Steel Reserve once my taste buds had deadened. The little homeless encampment was growing as I saw a few headlamps come into the area and set up. I was glad that no one camp around to harass us for money. We were not in anyone's way and we were not soaking up resources from the city, county, or state. We would clean up after ourselves and leave the place just as nice as when we found it. Maybe the Tribe would treat it differently, but this was home for us and there was no reason to abuse it. We wanted a place to sleep, not a place to party and beat a drum next to a raging bonfire while pretending to be "deep". A simple patch of ground with a water spigot. I'd be gone in the morning. Some others would stay. But the patch of ground in the forest was home for the night and I appreciated not having to jump someone's fence just to have some place to, as Jason might have said, lay my neck.