In Which we Remember that we are in the Coast Mountains

August 15, 2007

The warm sun again was the trigger that woke me from a deep slumber. I had heard Bob get up and leave the tent earlier, and he and Mike were talking outside. I stayed in my bag, hearing bits and pieces of the conversation before realizing that it was one that I definitely needed to hear. I put my boots and hat on and stepped out of the tent into the open air. Mike was in trouble, which meant that we were in trouble. His wrist, hurt on the first day, was obviously not just sprained. It had been seven days since then and a sprain generally gets better with time, not worse. His wrist had been getting worse and worse and last night had been a tortuous one for Mike. We slept head-to-foot with Bob and I on the outside and Mike on the inside. At some point in the night I had rolled over and bumped into Mike's arm. Pain seared him, with the feeling of bone grinding on bone. He had left the tent and nearly vomited from the pain.

The rest of the night had not gone well for him. He had spent the time contemplating the future of the trip, sleep denied him from the hurt in his arm. He knew now, as we did, that his arm was broken and that it was getting worse. He had debated in his head what to do. We had an obvious option of retreating out to Yehiniko Lake. The satellite phone we were carrying could actually be used to call Doug and arrange a pick up at the lake, though this would mean abandoning most of our food cache. We had gotten a first ascent in and the trip could be declared a success. Mike could get medical care for his arm and avoid permanent damage. It seemed like the easiest decision to make.

But, for better or worse, this isn't Mike's nature. After much internal discussion, he decided that he wanted to go on with the trip. We were here and, as he said, he would just have to suck it up. I wasn't so sure. Had it been my arm, I'd have wanted to get out as soon as possible, not go further into uncharted lands, and certainly not try to climb anything. He was effectively one handed now and climbing would be very difficult. Arresting on snow or ice would be impossible. Though he was the least likely to fall during roped travel, if Bob or I fell he would not be able to help in the arrest. Which meant that all three of us would fall.

We drank tea and talked about the situation. I knew Mike well enough to know that once his mind was set, it was very difficult to change it. Instead of trying to convince him of the wisdom of retreat, we talked instead about what we would do with the remaining time we had up here. Today was going to be a rest day for sure, not just because of yesterday's efforts, but also due to needing some time to think. Ambition and Endeavour were, unfortunately, quite out of the picture now. Dokdaon was the easiest of the three according to the Hardmen of '67 and might still be a possibility. Easier peaks on the upper Scud could be in. We had six or seven days remaining before we needed to begin the exit out via the Scud. It was unclear what we would find once we got off the glacier and began the low traverse through the water shed of the Scud river to the Stikine, but seven days of travel seemed like a conservative estimate. I joked with Mike that what we needed was a good week's worth of nasty weather to confine us to the tent and keep us out of trouble. Though Mike laughed, he had been thinking the same thing.

In the afternoon Bob disappeared for several hours as Mike slept in the tent. We had used a SAM splint on his arm and tied it up as effectively as we could. Unfortunately, we had only Ibuprofen in our medical kit, which would do nothing for his pain. I sat in the sun writing in my journal, trying to record the thoughts in my head. When this proved too arduous, I turned to reading Gods and Generals. This rather poor offering was all I had. And when reading was too difficult, I just sat and looked out at the mountains, thinking about what to do and if I ever wanted to come back to this place. Expedition climbing in unknown lands was stressful to me. The sitting-under-a-tree thing came back to my mind. After the 2002 trip to the Hickman area, I swore off such expeditions. They were just too hard. I had sworn then that I would never come back. But here I was.

The afternoon stretched into early evening and Bob returned and Mike woke up. We made soup and sat in the tent playing cards. Mike had hauled along a book with many card games in it and we tried a variety of them. Mike couldn't shuffle. Nor could he light a stove. I started to make an effort to convince him that we probably shouldn't continue on into the unknown, that his arm needed to be looked at. But I didn't get much past the first sentence of the speech that I had been working on earlier in the day as I sat in the sun above the glacier. I knew it wouldn't work.

We ate dinner and discussed tomorrow. A high pressure system seemed to be sitting on us, which meant that the weather should be good and we would have to find something to do with our remaining time here. We couldn't just sit around in the tent for a week doing nothing while there was fine weather outside. Tomorrow we would move to a camp near Dokdaon and the food cache. Mike seemed optimistic and Bob agreed: After moving, we'd try for it. We'd try for Dokdaon and a second ascent, 40 years after the first, on what the Hardmen of '67 called excellent, third class rock. We couldn't just sit and do nothing.

Moving day. But this moving day promised more than others. We were leaving terra firma, leaving our excellent campsite on the rock of the col, with plenty of places to sit and rest and dry stuff in the sun. We were leaving the safety of the col for a land of snow and ice, and we would not return to soil, or rock, until we got off the Scud, perhaps in eight or nine days. We took a leisurely approach to the morning, spending two and half hours drinking tea and eating breakfast and packing up our gear. When we shouldered our packs, we were reminded of how much stuff we actually had. The traverse out would feature even heavier packs, as we'd have all of our food with us in addition to all the junk we were currently hauling around. Around 10:30 we headed down to the glacier, roped up, and began the slow descent down to the Scud, following our tracks from several days earlier. The glacier was still in fine condition, with no new crevasses, but many new patches of bare ice. The sun had worked hard over the last few days.

The view from the Scud up to Dokdaon was encouraging. The angle of the south ridge seemed fairly moderate and, if the rock was stable, could provide a reasonable way up. The hard part seemed getting up the glacier spilling off the east face down to the Scud. It looked broken and crevassed, but maxing out at a moderate 45 degrees. We gained the Scud and traversed around several glacial pools and past yawning crevasses to reach the comfortable snow in the middle of the glacier.

The walk to the food cache took barely more than an hour of our effort and sweat, for with the cloudless skies the sun bore down upon us without any intermediary to soften the blow. The col disappeared from sight, as did White Rabbit, though parts of Blaster Ridge were still visible, as was the whole of Dumper Ridge.

At the food cache we sorted through food, trying to guess what we wanted to eat for the next few days. It wasn't especially important, as we were planning to put a camp in close by and could come back for food when we wanted it. The crevasses in the central portion of the Scud were still well filled in with snow and the glacier was almost flat here: It was like walking through the prairie, though instead of grassland we had a lifeless zone of snow and ice.

After selecting our meals for the next few days, we re-sealed the dry bags and moved up the Scud toward Dokdaon, eventually settling on a camp near its base about ten minutes from the cache. There was a convenient crevasse nearby that we could use as a bathroom and the view from the camp was phenomenal. An ice and rock fall (thanks, global warming) close by promised running water, but after watching rock and ice falling down from it (hence the name), we decided that it might be better to melt snow instead. Besides, we had lots of fuel left and really did need to use it up if we didn't want to haul it out with us.

After getting the tent set up and well anchored, we sat down for a communal meal of spiced gouda and sausage, wrapped up in some of Bob's tortilla. I began to feel ill. Not from the fat laden food, though. A head ache appeared. My stomach was upset. I felt a sludge in my blood. In short, I felt like I was suddenly hung over from a night of too much beer. When Mike and Bob set to building various features in the snow for our comfort, like a kitchen and a privacy wall for the toilet, I could barely move. They shooed me inside the tent and out of the sun, a victim of a case of sunstroke. Sitting in the shade of the tent helped, though when ever I tried to stand up outside the tent and help, I had to immediately retire once again.

An hour passed and I began to feel better. I drank down an additional liter of water and tried to relax as best as I could. As the afternoon lengthened and the sun got lower on the horizon, I was finally able to leave the tent to help with some chores, not that there was much left to do. I finished digging out the kitchen as Bob melted snow for drinking water.

The three of us had nearly a nine liter water capacity, and we would need all of that filled for the climb tomorrow of Dokdaon. Additionally, we would need five liters of water for the morning, to make tea with and to re-fill what we drank over night. Melting that much snow takes time. A little "seed" water goes into the pot, which is then packed with snow and placed on top of the stove. As the snow melts, more is added until the two liter pot is near capacity and the liquid drained off. Although an easy task, it is an important one and one that takes time to do.

Dokdaon took on a new aspect from the vantage point of our snow camp. From close range, it too seemed small and easy, a short stroll from camp. The ice fall was the only serious issue to be dealt with, and a line seemed to present itself. It looked like we could go to the far end of the slope, and then angle up and left to avoid crevasses. A gaping one near the top appeared to have a small snow bridge on it that would allow us to get past it without too many problems. Then, traverse left below the rock on snow and turn the corner. Hopefully we'd find something good up there.

On the other side of the Scud sat the Doormouse,with its long ridge running to the summit. From the top of Dokdaon we should get a nice view of it that wouldn't be so skewed by the low elevation and close range of our two camps. Our route had come up the other side and gained the ridge near the summit. The notch was, again, barely visible from here, and looked just as innocent as it had from the other side.

The Nipple and Endeavour looked just as innocent, though I knew from the view atop Doormouse that they were much steeper and nastier than they seemed from down here. The Hardmen of '67 had climbed Endeavour, though it had taken them two attempts. On the first they had reached a false summit and there was no simple way to traverse from the false to the true summit. They backed down and then took a different route on the next day. The Nipple had never been climbed.

To the south lay our distant future, distant by a week. A week in the wilderness is quite distant indeed. Mount Hickman stuck its massive head into the few clouds that were in the sky. I was glad that we were not headed over there, and instead would take the kind Scud out to the Stikine.

Opposite the end was the upper Scud glacier, with an impressive peak that had innumerable routes on it, most of them hard. The only easy attack seemed to be a buttress that ramped up the near one of the summit pinnacles, though from its terminus to the top seemed a route of uncertain quality. If we were not going after Endeavour or Ambition, it seemed like a worthy objective.

Due to the prominence of the peaks above us, namely Endeavour and Dokdaon, the sun disappeared earlier than the at the col camp and the temperature instantly plummeted. Gone were the days of lounging around on rock. We were on ice and snow and it was cold without the sun. Soup, dinner, dessert. Sort gear. Melt snow. Make for the tent and the warmth. Although Mike's arm was still in intense pain, the splint helped significantly, and we only heard slight yelps of pain from him when he would forget his condition and try to use his right arm. Tomorrow would be the test case. If Mike could make it up Dokdaon, then we might be able to climb a few more peaks before beginning the traverse out. If not, we might be spending a lot of time sitting, or hiking, or doing nothing. Tomorrow would tell.

Something went bump in the night. I was awake. I could tell that Bob and Mike were both awake. I didn't know what woke us up, all of us up. We were alone on the glacier and the next human being was probably down at Yehiniko Lake, quite some distance. Though animals, and bears in particular, cross glaciers to get between valleys, we were not on any obvious transit route and had seen no tracks other than our own. A few second passed. And then the interior of the tent lit up with a white light. Brighter than the tent with direct noon sun. I could see Mike's face in the light, down by my feet. And then it went black again. A thunderous report was heard. A few seconds later the world lit up again and rain became to slam into the tent. Wind began battering the tent, shaking it around like dog does a chew toy. For twenty minutes we sat through the storm, with lightning pounding. Mike and Bob scurried outside to cover up gear that they had left exposed under the perfectly still, clear night sky. Rain came down in torrents. The lightning was striking the glacier itself, as well as the peaks around us. The tent shuddered under the force of the wind and I was thankful that we had guyed the tent out completely before going to bed. And then the storm switched off, leaving only a light drizzle and a gentle breeze.

At 4 AM, I heard Mike's alarm go off, mine having been turned off by its pessimistic owner, and saw him peek outside. He quickly returned to his bag and we went back to sleep. The drizzle was on and off, but the visibility outside was close to non-existent. His alarm went off again at 5 AM. Once again we went back to sleep. At 6 AM I heard it go off for a third time but declined to even open my eyes. We slept until 8:30, with the drizzle coming and going, but with nothing but grey mist to be seen outside of the tent. There would be no climbing today and our test of Mike's arm would have to wait for another time. We played several rounds of cards before the drizzle ended for good around 11:30 and we could emerge for our morning tea. The ceiling had lifted somewhat and we could see some of the mountains around us, including the lower reaches of Dokdaon.

The tea consumed, we made up a pot of hot lemonade and looked at the misty land around us. It was almost attractive, I thought. Though obscured, the mist gave the land an interesting perspective that was perhaps more true to the nature of the mountains we were in than crystal weather could provide. Although we could climb Dokdaon in the current conditions, it would be for naught: All we could do was summit, and we would have no views. Climbing it would be for the simple, and obscene, purpose of getting to the top. The process would not be enjoyable. Itching to do something, Bob took a look at the sky and declared it good. Indeed, a small patch of blue sky overhead could be seen. But so could a dark grey mass of low clouds rolling up from the lower Scud. Mike agreed to go to a walk up to the upper Scud with Bob, while I decided to stay put in camp, sure that the weather was going to degrade in a matter of minutes. Nearing 1, the two of the set out for a walk up to the top of the Scud and, hopefully, some views of our route up the lower glacier on Dokdaon. At 1:30 the weather closed in and I was standing alone next to the tent in a complete white out. The privacy wall of our crevasse-toilet, a mere forty feet away, was not visible.

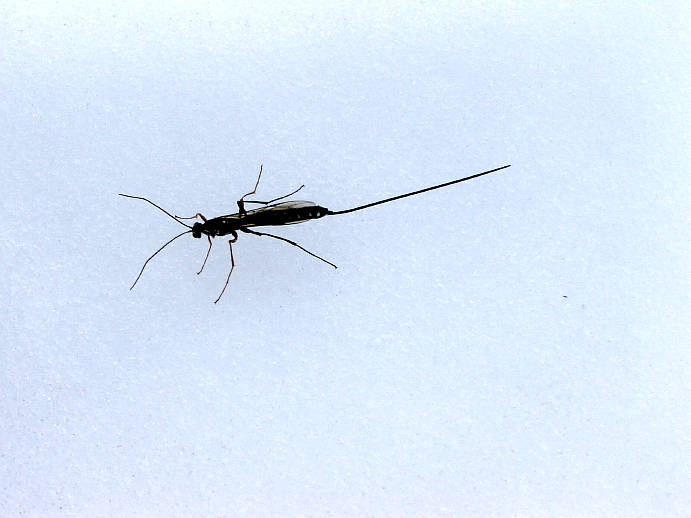

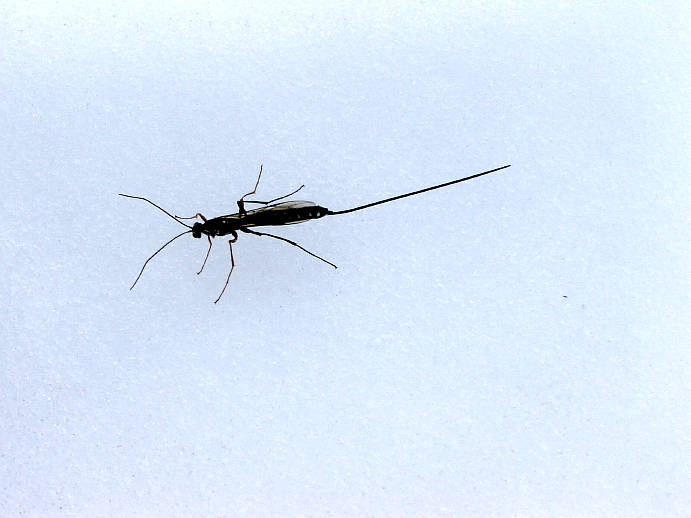

On a glacier there are few things that one can call alive. A high glaciated land is perhaps the environment most devoid of life. Even in the heart of Death Valley, at Badwater, there is life. Plants, insects, birds, rodents. Occasionally a hummingbird had visited us at the col camp, but now we alone were living. A few glaciers, like the Anderson glacier in the Olympic mountains, have oddities like worms inside of them. But here we alone represented life. But on their walk Mike and Bob found something alive. Or, at least, that was once alive. An insect with an impossibly long stinger on it was dying on the snow, far from where ever it was that it once lived. A stiff wind, perhaps the storm last night, must have blown it from a valley somewhere, from some small pocket of living matter.

With Mike and Bob gone I spent time writing in my journal and reading my book. I didn't have much of interest to write about, and the book wasn't very appealing, and so I focused on the dull topic of logistics. How much fuel we had gone through in how many days. How many times I had gone to the bathroom during the trip. How much toilet paper I had left and why it didn't matter, as we now had snow to use. I inventoried my food and estimated how much extra I had brought. The fact that I had not yet used my down jacket or balaclava. That the light sleeping bag plus insulated overbag was a fine choice of sleep system. About how awful the tea is. That my feet were still blister free. About how many clean pairs of socks I had (two pair). That the hot lemonade is a hit. And so on and so forth.

Eventually the drizzle returned and I left the kitchen for the dryness of the tent, where I could nap for a little while in the luxury of an empty tent. The drizzle stopped and around three I left the tent to make some of the tea that I had just recently complained about in my journal. It gave me warmth and caffeine, and this made the misty land around me seem, again, pleasant. Mike and Bob returned at 4 with stories of occasional views and a confirmation that our route up the glacier on Dokdaon would indeed go. Or so they thought. Tomorrow, perhaps, we could climb. I made soup and then dinner as my friends warmed up and dried off inside the tent. Or, more accurately, transfered their wetness to their sleeping bags. It was cold without the sun and it wasn't long before all of us were in the tent playing cards. We had learned two games so far, and if the weather was foul tomorrow, we were going to tackle a more complicated German game called skat. I peeked outside the tent as we were going to bed at 9 pm to see what the weather was like. I couldn't even see the base of Dokdaon. The optimist in me set my alarm for 5 am.

At 4 AM Mike left the tent to relieve himself and declared that the sky was partly clear, that he could see stars, that things looked good. At 5 AM the alarms went off and heads were stuck outside. It was mostly cloudy. At 6 AM, when they went off again, it was raining. At 8:30 AM we woke up, having been denied the early start we'd need for Dokdaon. But, perhaps the day would not be a complete loss. We learned the ridiculously complicated rules for skat, apparently the most popular card game in Germany, and drank tea inside the tent, sheltered from the rain outside. By noon a window of clear weather had settled directly overhead and we could see blue sky. However, the weather everywhere else was foul and grey. Just overhead, just for us, was a nice little patch of blue. We took advantage of the opportunity to get some exercise and ward off tent-fever for a while longer by making the short walk over to the food cache to pick up a few more supplies. It wasn't that we especially needed them. I had planned my food, as had Bob, around being active almost every day and needing massive amounts of calories. Sitting around reading and writing and playing cards meant that we were not eating through our food. That would make for heavy packs on the way out.

The pleasant weather continued into the afternoon, something that all of us noted. Perhaps we would be forced into a later start for Dokdaon? Perhaps we might have to descent in near darkness? Climbing and returning on a route of unknown direction in a whiteout was something that none of us wanted to do, though tent-fever might eventually overcome our more tempered thoughts. We sat in the kitchen chatting until the later afternoon, when rain drove us inside the tent for more cards. Though the precipitation didn't last long, and was never hard, it was accompanied by another complete whiteout. Mike's arm is doing better than before, with now three days of rest on it. Eventually, assuming he doesn't stress it, the bones will begin to heal, hopefully in a way that doesn't require a re-breaking when we get back to Vancouver.

After today we have three more days before beginning our retreat out on the 22nd. My thoughts have turned to that, have begun to focus on that retreat out. There is something comforting about beginning the walk out, as opposed to the danger of climbing. The way out could be very easy once we pass the ice fall at the end of the Scud. We had seen a photograph taken by a researcher from the Scud Valley showing the fall, and it looked ferocious. Hopefully there will be an easy passage on one side or the other. However, we've booked off an entire day just for the ice fall and 7.5 days for the entire walk out to the Stikine. From the maps and satellite photos, it seems that the Scud Valley should be passable, though the river might force us into the bush at some point along the way. The worst part of the waiting, for me, is the uncertainty before going to bed. We set out alarms, once again, for 5 AM, but the doubts in my head keep me from sleeping well. We can hope for the best, but it seems that the weather is keeping us from testing Mike's arm, and preventing us from doing something foolish, like trying to climb Ambition. If this goes on much longer, we may very well be at each others throats under the stress of doing nothing.

Five AM. Alarm. Head outside. Go back to sleep. Six AM. Alarm. Head outside. Go back to sleep. Seven AM. Alarm. Head outside. Go back to sleep. Turn alarm off. Another morning of no visibility. Another morning spent playing cards and drinking tea inside the tent. Tempers are beginning to flare. Talk is made of trying Dokdaon anyways, regardless of the weather at the start, in hopes of a window in the afternoon. Indeed, we got a window at 10. Bob was chaffing to do something, and so we decided to go for a walk up the glacier at 11, with the weather looking ok, but not great.

The weather, and being confined with each other in the restricted area of the tent, is beginning to takes its toll on us. We no longer refer to each other as Chris or Mike or Bob. I'm known now to them as Fartsack. Sometimes Fartsack Jones. Mike is called Lefty. A Bob is known as Count Bobula. Or Count Blobula. Or Bobtimus Prime. Or just Larry. Small digs at each other than a few days ago would have been taken with a smile or a grin are now felt more personally. The Canada-US rivalry, once friendly, is becoming annoying. And there is nowhere to go to escape ourselves. Fifteen minutes up the glacier, I had had enough. And what was it that pushed me over the edge? Some nasty comment? Some snide remark? Nothing of the sort. Rather, I was walking the steps of Mike or Bob, whomever was in front of me, to make passage on the snow a bit easier. A few comments from them and their taking to walking in circles was all that did it. Rather than explode (explode at what?), I pointed to condensation in my camera and walked back to camp to be alone for a while. Reading what I wrote in my journal from that day reveals the state of mind of a person trapped with others in a confined space for even a few days. Perhaps this sort of thing hits others to a much smaller degree, but for people who are used to spending time in the freedom of the outofdoors, being penned in is something of a torture.

I returned to camp and sat under the window of blue, directly overhead, that was becoming a daily occurrence. I brought all of our sleeping gear outside of the tent and dried it in the sun. I was enjoying being alone, of not having to deal with others. Of being able to simply be, instead of having to endure the others' barbs, and send out my own. I wrote horrible things, thought horrible things. I sat in the kitchen. I napped in the tent. Meanwhile, Bob and Mike were exploring around the upper Scud, finding little oddities to marvel at. A big rock, for instance.

Hours passed and the weather, once again, closed in during the later afternoon. I made tea to warm and cheer me while I wrote more terrible entries in my journal. I wrote not to try to exorcise them from my head, but because I knew, down inside of me, that I'd want them around as a record of my mental state during the trip, to remind me of what I was thinking about, what was going on inside of my head. And to vent. By six the boys were back in camp, having navigated through the usual early evening white out.

They dried off inside the tent while I made soup and dinner, though this time I did not join them inside. I wanted space, I wanted quiet. I wanted to interact with nothing, to have my own world around me, a world of my making, a world that didn't have others inside it. Once I got into the tent, I reasoned, that world would come to an end. And so I sat outside eating and watching the weather come in and out. Toward eight it began to clear and things looked promising for the next day. I wasn't certain that I wanted to climb tomorrow, but I was certain that I didn't want things to go on like this for much longer. I didn't want to dread spending time around Mike and Bob. I didn't want to dread the confines of the tent. Too much time doing nothing wouldn't have affected me so much if I was alone. If we were going to be cooped up, we needed physical activity to temper us. I crawled inside the tent at 8 and declared the weather to be good. Then I went to sleep. With my earplugs in.

Despite the promising weather when we went to sleep, I woke up at midnight to pull out my ear plugs and heard the sound of rain on the tent fly. The rain continued on and off until 3 AM and at 5 AM the clouds were thick around us. The pattern was repeating itself. Another day here on the ice. I ignored the others and stayed huddled in my sleeping bag, earplugs back in, until 10 AM when the drive to use the bathroom was too great. I eventually roused myself and made tea for us, and even enjoyed playing cards for a while.

Outside of the tent the weather was getting better and Bob proposed climbing the glacier portion of Dokdaon. I had no intention of doing so, as the weather was only good in comparison to other days and I had no desire to ascend a glacier and then descend it in a white out just for exercise. Mike, though, was of another mind and decided to go. I was happy with this as I would get a bit more time alone, even if it meant doing nothing. By noon the plan had changed and they had decided to try to climb one of the minor bumps on the upper Scud. Seeing weather coming up from the lower Scud, I still had no intention of going anywhere. Bob seemed a little disappointed in this, but I was not to be moved. We decided that if they didn't come back by 9 I was to come looking for them. And with that they were off. And within 45 minutes of leaving, the weather had sealed off the area and all I could see was mist.

I spent the day sitting in the kitchen reading and writing and thinking about the future. I wrote and wrote and wrote some more, though my journal was thankfully free of any nastiness. Having spent most of yesterday alone helped a lot, and more time spent alone is further healing my mood. Tomorrow is our last shot at Dokdaon, and if the weather doesn't cooperate we'll probably try to climb anyways. By the mid afternoon the weather had stabilized and I could see the peak that Mike and Bob had set out to climb. I thought I spotted them, but realized that the objects that I thought might be them hadn't moved in some time. Either they were hurt and not moving, or I was looking at rocks. A rim of blue is hanging out to the east and the top of Dokdaon is actually visible, a first in many days.

I made tea and sat some more, having run out of things to write about. Gods and Generals finished, I took to reading one of Mike's books instead. And then I sat some more and did nothing. And was content. I was content in the mist and the snow, just doing nothing with no one else around. Some how doing nothing while in town is aggravating. Being alone while in town is lonely. But it isn't so outdoors, or at least it wasn't right now.

The boys returned at 7 with a tale of a while out and a successful summit of the peak, or bump as they described it. It had been snow and no views all the way and they were cold and wet and went straight to their bags as I made soup and dinner for us. The weather, following its normal pattern, was lifting and there was, once again, a promise of a better tomorrow. In some ways it didn't matter. Whatever we did tomorrow, we'd be leaving the next day. We'd start walking toward the end of the trip. We'd have a concrete goal in mind, a definite purpose. Perhaps we wouldn't wear on each other quite as much. Perhaps I could again interact with the others without getting annoyed or frustrated. I hoped.