The Most Unpleasant Hike Ever

August 24, 2007

"We shouldn't be here," said Mike. It was an odd thing to say, I thought, given that the chances of us being in the wrong valley were slim. But then I looked at the map and had to agree. The old, 1970s vintage, Canadian government map of the area showed that the valley we were in should be filled up with ice. But were were a good kilometer from the Scud glacier, standing atop a knoll, looking down to the flood plain of the Scud. The glacier had retreated perhaps two kilometers since the map was made. Some grad student should write a paper about this.

The sky was grey and rain had been sprinkling on us, off and on, since we left camp at 11. After a short climb to the top of the knoll, we began a bushwhack down to the flood plain itself, passing through many pleasant flower meadows along the way.

The weather overhead couldn't discourage us, for we were making progress toward the Stikine and that progress was easy. And would hopefully continue to be easy.

But once we reached the flood plain, all that began to change. We had several large fords, including the outflow of the glacier coming off of the glacier in the U-Vic calendar, wetting our feet and pants. Even with all of the time spent in the snow on the glacier, our feet, except for Mike's, had remained relatively dry. After traversing through the plain, we climbed up onto a rocky plateau to escape the main channel, which had swung from the center over to right side of the valley. At least it was a short, open climb.

As we moved down the plain, vegetation began to become more common, and the shrubs larger. Occasionally a side stream would come in, which we'd be required to ford. As I was mid way through one of them, I heard a cry and looked back to find Bob standing still, his legs disappeared into the rocky soil beneath him. He was stuck to his knees. Mike, close by, was in to his thighs. They were stuck in quicksand. Now, quicksand in reality doesn't work like it does in the movies. It doesn't swallow you up, but rather just gets you stuck, and stuck tight. Somehow I had managed to step in exactly the right spots and missed it, but the others were not so lucky. I worked my way over to then and helped them get unstuck, but in the process managed to get stuck myself. We worked and sweated and cursed, and cursed some more, and then let out a few oaths and cursed some more. But we eventually managed to struggle out of the quicksand and onto more stable soil. Bob was the only one willing to take a bath in a cold stream to wash off the mud and grit.

We continued our progress down the valley, taking care not to get stuck in any more quicksand. Of course, we managed to get ourselves stuck once more. The rain continued, but the foot of the Scud glacier was growing smaller and smaller as we worked our way down the valley. Oh, and it was raining.

The main channel took another swing to our side, forcing us into a dense thicket of slide alder and down trees that we had to battle through in order to continue to make progress. At this point I should mention that we were nearing 300 meters above sea level, and I should remind the reader that this part of the New World, from Alaska down to Oregon, is a rain forest. That means that bush is thick and progress through it was agonizing. Slide alder was everywhere and thick enough that pushing through it was very difficult, especially with large packs that had many things strapped to the outside. Pickets would catch. Ice axes would catch. Boots would disappear in mud holes. Drizzle continued.

But at least the land was flat, and the bushwhacking sessions would last for no more than forty minutes or so, when we would emerge into a pleasant meadow and could walk normally once again, at least before the river forced us back into the bush for more battles with slide alder and downed trees.

When possible, we'd scramble higher up and gain rockslides. Although you had to be careful when moving along the rocks, they were clear of brush and other nasties, and progress was comparatively quick.

As bad as the bushwhacking had been, it was gentle compared to what was coming up. After a nice break for lunch, during which time it didn't rain, we finished up a nice walk through a meadow and come upon the main channel.

We had been very careful not to enter the river, which was fast and deep, even if it meant detouring into the brush. But we were now faced with a choice that made the river seem the more appealing option. The main channel was split in two and the other side looked nice, open, and pleasant. If we stayed on our side, we would have to bushwhack up and over a point of land that came straight down to the water. We decided to try the river and with relative ease made it across the first channel. But the second one didn't look, well, safe. I dropped my pack and waded out to test the water, making it 15 feet into it before being forced back. The water was already well above my knee and churning fast. Bob made a similar experiment with similar results. That meant crossing the point of land through the brush. I went as far on land as I could, then tried to move along a small backwater to get to the point, but managed to fall off an underwater cliff. My camera was soaked, done, finito. It would have to get very sunny in order to dry out, and currently it was raining.

We regrouped and crossed the backwater safely. We took a very steep gully up for a little while, battling through the usual slide alder and, now for the first time, devils club. We forced our way up the steep hillside, kicking steps into the mossy ground where we could, fighting and scratching our way up. Frequently I was down on all fours, in four wheel drive mode, to get up. The battle did not end until we reached a high plateau where the vegetation was less dense, the slide alder having been blotted out by larger trees. While not fun, the walking was at least not painful. It helped that we picked up a grizzly trail along the plateau. Grizzlies are large enough, and powerful enough, that when they move through the brush, they create a trail after a few uses. Grizzly bears frequent the same areas, season after season, and a trail develops where they walk. Of course, being lower built they don't knock away things like slide alder that, for us, are chest level. The rain continued.

An hour passed in the brush. And then a second, before we began to descend down, following a gully steeply down through devils club and slide alder, which at times became so thick that I couldn't see my feet. Everything that we pushed through was wet, which meant that we were soaked through to the skin. Finally, almost two and a half hours after we began our bushwhack, I gave a cry of triumph and emerged into a pleasant meadow free of brush. Our victory was short lived, however. Not twenty minutes later we came out onto the banks of the river and saw another such point of land. We would have to do the same thing tomorrow. The rain had slackened and we took the opportunity to throw up the tent along the banks of the river, in the mist. The hot soup we brewed up never tasted so good, its warmth doing me much good. But even hot soup wasn't enough to chase away the specter of what was waiting for us tomorrow. The rain returned and we dove into the tent, hoping to wait it out and be able to eat dinner in a civilized manner. Mike fired up the GPS and took a reading, frowning as he did. He checked the map, and then did so a second time. We had spent 7 hours traveling from our previous camp in the meadows to here. The GPS told us we had come 8 kilometers, as the crow flies.

All thoughts of taking a rest day vanished. We would need all of the available time we had to make it to the Stikine in time for our pick up. The land gave every indication that passage was going to become more difficult, not less. The weather was getting worse, not better. The collective mood sunk, and only a few words were spoken as we sat in the tent, listening to the rain fall over head.

I am warm. I am dry. I am not leaving this sleeping bag, no matter how badly I have to go to the bathroom or how much my mind tells me that we need to start moving. My bibs are soaked. My jacket is soaked. My socks are soaked. My boots are soaked. My hat is soaked. But, here in my warm cocoon of down and Primaloft, I am dry. I know what awaits us outside of the tent. It had rained on and off all night, and it was raining now. Not hard, mind you, not a downpour. But rather a soft caress of liquid. Which never ends. We eventually got out of the tent for tea and breakfast, the only motivation being our hope that perhaps the Scud valley would take it easy on us today after the initial thrashing. I stood in my wet boots, the water squishing between my toes, and looked downriver, hoping that I might see something encouraging. I saw only the river, pinning us against a headland. Into the brush almost immediately, I thought. At least we wouldn't have to suffer while anticipating the suffering. We would just suffer from the very start.

With sluggishness, we broke down camp, shouldered our loads, and moved over to the start of the brush. We hoped for a game trail, a grizzly track, anything that might help us, but finally just went straight up the hillside, pushing through the usual mix of devils club and slide alder that choked the lower regions of the hillside. Though it meant gaining elevation, it was faster, and less frustrating, to climb up the hillside, sometimes on all fours, to where twin horrors didn't grow.

Up we went, until the brush got slightly less dense and we were able to follow a grizzly track as it moved along the top of the headland. Trust the animal, we all thought, they'll take the most efficient way. Of course, what is efficient for a animal that walks on all fours, and doesn't have three ice axes on its back, is not always efficient for us. Tempers began to flare. Not so much at any of us, but at what we were doing. It wasn't even noon.

We finally dropped out of the brush and into a long, wide meadow with only a few trees about. The meadow used to be, perhaps a few weeks ago, strewn with wildflowers. Now, it is was strewn with their dying bodies. Winter was coming, and the plant world knew it was time to run and hide. We separated a bit during the walk through the meadows, trying to regain some composure, to let tempers subside, to try to regain some composure. It was too far to the Stikine to lose it now. We couldn't allow ourselves the luxury of coming apart mentally this far from the end. I tried to focus on the beauty around me instead of the ache in my shoulders, in my back, in my arms. Instead of my wet feet, the skin on which was quickly beginning to break down. Instead of the big toe nail that I had recently lost. Instead of the monotonous diet of energy bars and nuts. Instead of the devils club spines embedded in my hands, arms, and legs. I would have taken a picture of the misty river set in the background of the red meadows. I would have, but my camera was completely soaked from the spill I took in the Scud yesterday. One more thing to try to de-focus.

The meadows ran for perhaps three kilometers, a nice long stretch. Indeed, probably the longest brush free stretch we'd had since leaving the foot of the glacier. The three of us reunited on a big, dead tree and some of Bob's mother's raspberry fruit leather. He estimated that he had brought 12 pounds of fruit leather, in the raspberry (best), rhubarb (also the best), and apricot (also the best) flavors. We liked the fruit leather very much. In front of us was another headland to be passed. We would have to enter the bush for a while before beginning the climb up and over it, but fortunately found a grizzly track along the bank to follow, having only to battled a few specimens of devils club and slide alder along the way to the headland.

An hour of only moderate suffering got us to the headland, where the real suffering began. Up we went, climbing the headland, through stands of trees and thick brush, trying as best we could to maintain a calm disposition. The zen of bushwhacking, if you will. Another hour passed before we finally topped the head land and began traversing around it. Our traverse took us across scree fields entirely carpeted with soft, squishy moss. We only know of the rocks because our boots would tear away pieces of the moss, exposing the rock underneath as we struggled not to fall down. With 70 pounds on your back, and change in body position begins the falling process.

The headland continued on and on, and we could see the Scud and its flood plain below us. The main channel was against the banks, and we had to continue our scree and talus traverse. Despite its slowness, it was preferable to batting the devils club and slide alder (a pox upon you) lower down. Except for when Mike would get off balance, and reach out with his right arm for balance. Then he would let out howl of pain, followed by a few gasps of quick air, followed by a long grunt.

Then we heard a sound through the misty air. We had been alone with ourselves and the land for so long that the presence of a foreign sound was instantly recognizable. We looked around and around, and finally spotted the invader: A heavy lift helicopter was bringing supplies into the Galore Creek mining area. The mouth of Galore Creek, coming down through an evil looking valley, was opposite us, hiding on the other side of the Scud. Back at home, safe and warm, I thought it was a good idea for us to go over and check out what was happening with the mine. It was folly now.

Galore Creek is being developed by NovaGold Resources, a mining corporation with many interests in resource extraction and exploitation of the Great North. Galore Creek is their furthest south development, with most of their interests lying in western Alaska. Before I go any further, let me add that companies like NovaGold bring a lot of hard currency to underpopulated regions. They provide jobs and benefits for people who would other wise lack them. They pump a lot of money into local economies through high wages to workers of all skill levels, through the royalties they pay to provincial, state, and federal governments, and through the fees that First Nations and Native Americans charge them for access to their land. I say all this in an attempt to keep things in perspective for those of you reading from the comfort of an easy chair, while sipping a $4 Starbucks drink. People of the North need jobs and companies like NovaGold provide them. The people of the North do not need to be told, "Sorry, tough luck, you need to move south to a big city and get a job working at a Wal-Mart because we down here in Vancouver don't want you to dig into the earth." Only so many people of the North can be employed as fishing and hunting guides. There is only so much cultural and outdoor tourism to be had.

But the cost of these jobs is high: Wildlife killed or driven off, streams polluted, mountainsides removed, and one less wild place on earth. For many years companies have been wanting to exploit the natural wealth of the Coast Range and its environs. Beginning with forestry operations, companies and individual prospectors explored the area, looking for something that they could take out and sell to others. In 2001 and 2002 I had seen the core samples and claims on the Arctic Plateau, left by drillers, in violation of Canadian law. Although extensive mineral deposits were found, the prices for such things were too low to justify the expense of extracting them: There was too little infrastructure. Namely, there were no roads leading to the areas of interest and the cost of building the roads would have outweighed the value of the resources taken out by those roads. Until recently, that is. The cost of raw materials, such as copper, have skyrocketed of late, as the economies of the developing world ramped up into the industrial age. The price of gold has doubled, caused by foreign demand and a weak US dollar. The time for exploitation was right. Galore Creek, miles from the nearest road, a pristine valley and mountain complex, was the target. It was time. NovaGold even made a promotional video, which I'd highly recommend watching.

The development at Galore Creek was not to be a small one. According to a recent feasibility study, the Galore Complex holds "Proven and Probable" reserves of 5.3 million ounces of gold, 92.6 million ounces of silver, and 6.6 billion pounds of copper. Recent values for these metals are $3.50 a pound for copper, $807 per ounce for gold, and $14 per ounce for silver. Using these numbers, we can see that the Galore Creek complex is holding about $28.6 billion dollars of wealth. NovaGold owns half of that wealth, or about $14.3 billion dollars. Along with the other partner, NovaGold will invest $2 billion into the Complex in order to get it to production stage. The numbers show, quite clearly, the value of the area for the company. And to the Canadian government in Ottawa. And to the BC Provincial government in Victoria. And what about the people of the north? 1000 construction jobs and 500 jobs once operations begin. 500 jobs for an estimated 20 years of production. 500 jobs in return for destroying a wild, untouched place.

And what of the Tahltan First Nation, on whose land the mine is to be developed? The government of the First Nation approved the development, in return for some financial benefits and increased electrical power. Many members of the Tahltan First Nation will be employed by the mine. Tahltan businesses will increase their revenues due to the influx of cash into the local economy. However, a group of Iskut elders, called the Klabona Keepers isn't quite so happy with things. The problem for them isn't so much one mining project. The problem is many. To quote from a statement in February of 2006,

"Our people want a future, good jobs and to protect our lands and culture for generations to come. We can do this by developing one resource development project at a time in the right location," said Rhoda Quock, spokesperson and chair of the Iskut Elders organization Klabona Keepers.

"The Iskut and Tahltan communities are having difficulty coping with the problems associated with the existing mines," said Iskut Community Liaison Eileen Doody. "For all of the proposed projects to go ahead would mean nothing less than cultural genocide. Our land, our Tahltan people and the wildlife would be devastated."

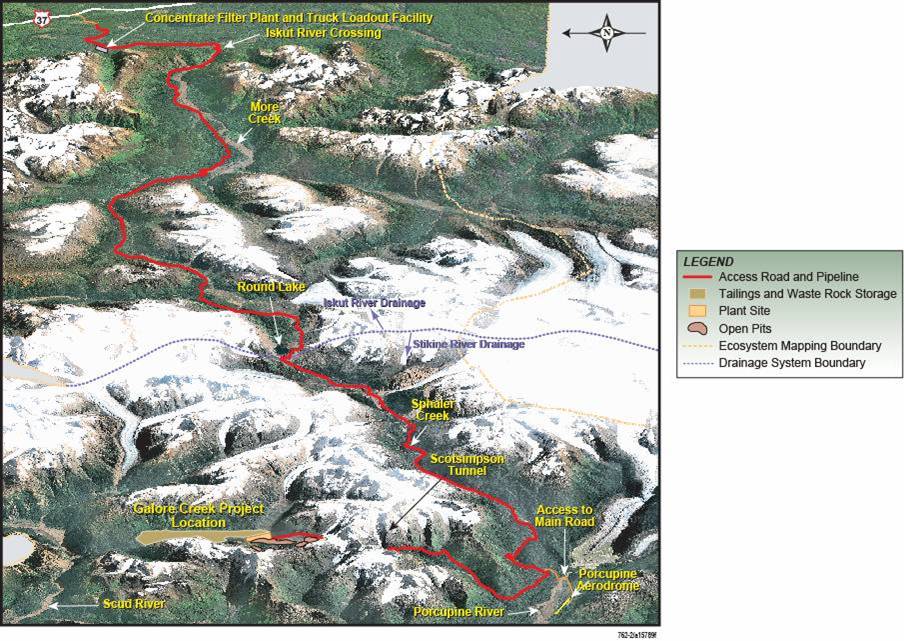

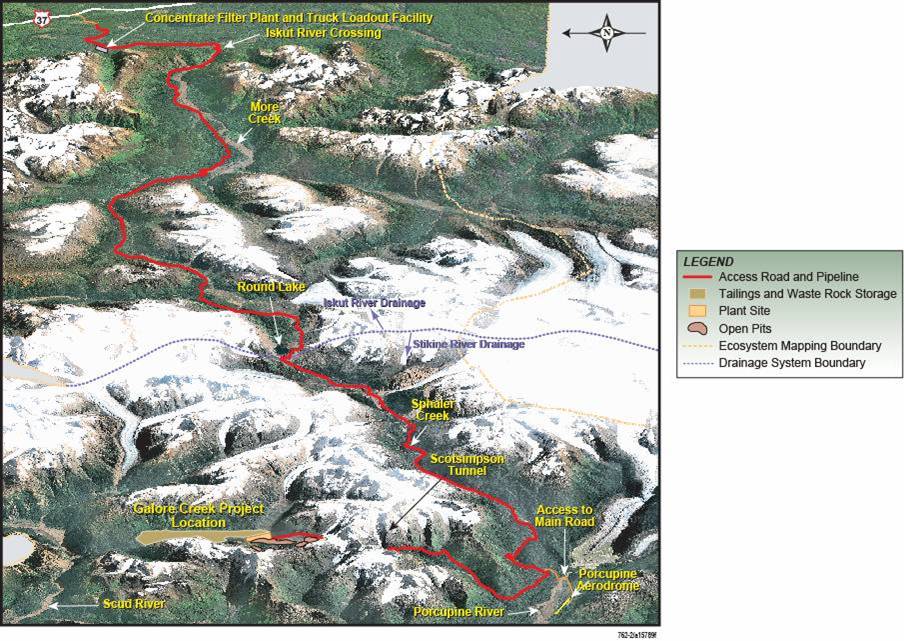

The Galore Creek Complex will be a massive, open pit mine, with an estimated 10 separate mines operating. In order to get to the mining area, a massive road building project is on going, stretching more than 70 kilometers from HWY 37 to the east. The company was kind enough to put a picture of it on their website:

We were standing in the lower left corner, traversing around the banks of the Scud, and looking up into the valley. As you can see, the road is extensive, and even involves drilling underneath an ice sheet to reach the main area. Previously untouched wilderness will eventually be a roadside attraction. Wildlife will, of course, be effected, but when push comes to shove, people would rather take a paycheck than worry about a healthy grizzly bear population, or the extinction of fish in the streams. But, of course, the Canadian government signed off on the environmental impact, so everything must be ok. Or, perhaps, the wealth of the area was just too great, the perceived economic benefits to the Tahltan just too high.

In some ways the reasons, the intentions, become unimportant. At some point, one only looks at the results. In the end, a formerly wild area will be destroyed, a new road introduced, wildlife driven out, fish killed, and pollution dumped into the general environment. Believing otherwise puts too much faith in the truth telling ability of governments. When enough has been extracted, or when the price of gold, copper, and silver drop too low, the company will leave and the earth will begin to try to heal itself. There will be one less wild place on earth. But, by then there will be another mine, another logging area, another resource project. Perhaps they'll dam up the Stikine to generate power. Every one needs power. Power brings jobs, and jobs are good. Development is a good thing, right?

We traversed on, the mouth of Galore receding into the distance very slowly. I wondered what the chopper pilots thought when he saw us down here, if he saw us at all.

We finally got off of the talus field on the other side of a long bend that the Scud took near the mouth of Galore Creek. I was tired. We were tired. It had been raining on and off all day long. We had been in brush or on rock most of the day, and it looked like we had more of the same in front of us. Back into the slide alder and devils club. Scratching at us, tearing at us, tormenting us. Onto all fours again for a steep climb up a headland. Two hours of suffering got us through the headland and down to the other side, where the land was flat, but choked. Frequently it was easier just to walk through a side stream than to battle the brush. We fought through a copse of trees and came out to a beaver pond.

I was too tired to walk around the edges and battle the brush. Instead, I just forded the beaver pond, its waters coming up to my waist. It didn't matter. I was already soaked. I sat down on the other side and waited for Mike and Bob to come through the brush. If I wasn't moving, I was sitting.

The day was getting long, and we hadn't made as much progress as we had hoped. Every time we entered the brush our pace dropped to a kilometer per hour, if we were lucky. The rain returned as we trudged on, heads down. We were walking on the banks of the Scud, not wanting to look up, for we knew what was awaiting us. The river was going to force us again into the bush, was going to force us up and over another headland. The suffering was not going to end, only to continue. It was 6 pm and we had been cold and wet most of the day, except when we were going up a thickly choked hillside, when we were hot and wet. A side creek came crashing down from a water fall above and there was enough mostly flat land to pitch the tent.

Only the fewest possible words were exchanged as we set up the tent in the light drizzle. Nothing was said as we greedily drank down our evening soup. Nothing was said as we ate our dehydrated dinner. The rain continued to fall. I ate as quickly as I could and then stored my gear before hopping inside the tent. Inside the tent I could take off my wet clothes and my wet boots and try to get dry inside of my sleeping bag. Inside the bag, inside the tent, there was no Scud River. The devils club and slide alder disappeared. There was nothing outside of my warm little sack. I didn't want tomorrow to come. I wanted to stay in my bag forever, my head eternally in the sand.

I was dry again. Warm. Safe. There was no slide alder or devils club here. But if I wanted to get to the Stikine, I would have to leave the protection of the tent and my sleeping bag. We were not covering as much ground as we had thought we would be able to and needed to start the day earlier than usual. At least it wasn't raining on us. The Scud valley was misty, as usual. Looking upstream, the beauty of this place was overshadowed by the specter of the work in front of us. We had another headland to pass, and even though it wasn't raining at the moment, the bush would be wet, which meant that we would be wet. Let the suffering continue.

We were moving by 9:30 and had a glorious walk of half a kilometer before the river forced us into the bush and up toward the headland. The pattern of every other bushwhack continued. Low down, we battled the twin horrors, working hard to gain elevation and leave them behind. Scrambling on all fours at times, we slogged up the steep hill side, clambering over downed trees and cursing huge slide debris than took forever to fight through.

With any luck we would find a grizzly trail near the top of the land and take it through the relatively open highlands. Well, there was no grizzly trail, and open highlands is about the stupidest thing I've ever written. They're only open in relation to the evils of the low lands. In order to retain any semblance of sanity, in order not to shout and curse and scream and bicker and fight and argue and hate, in order to be survive mentally, you have to have some way to mentally relax and let go. You need to have some sort of Zen thing in your head to keep moving forward. I pretended I was a bear. Mike, in between howls of pain from bumping his broken arm, kept focusing on making forward progress, no matter how little. Bob, well, Count Bobula didn't say much of anything.

After three hours we finally fought through the last of slide alder and reached a pleasant meadow leading to a sandbar, which led directly to another bushwhack. Ten minutes of being in the open was our reward for three hours of suffering. And this one had the look of being the worst yet. The headland was nearly vertical and several rock bands could be seen. We would have to take care, and have some luck, not to stumble upon one of them and get cliffed out. I sat on a log and felt sorry for myself.

I had been feeling sorry for myself for the last three days, so the feeling was nothing new. There was nowhere else to go and the only thing that kept me moving forward was the knowledge that it was the only direction to go. I couldn't, we couldn't, sit on the banks of the Scud and wait for a boat to come and get us. It was unclear that even a shallow draft jet-boat could get up the Scud to us. Maybe the Galore Creek people would chopper us out? No, the only thing to do was to go back into the brush and try to make progress.

We fought and fought and fought and fought some more. Progress was measured not in kilometers, but in meters. We would reach a place of relative flatness and openness, which just means that a devils club wasn't jammed into my ribs, and rest and look down at our previous resting spot, 30 meters below us. 15 minutes below us. We encountered some cliff bands and had to ascend higher. At one point we reached the end of a gully we had been following up, which had a steep headwall and a waterfall coming off of it. Although pretty, it meant the end of our line. We climbed steeply up the wall of the gully, through avalanche debris, kicking steps into the soft, squishy ground or decayed trees, trying to make progress while avoiding grabbing a devils club for support. As there was nothing else to grab onto, I clawed the ground with my fingers. When we finally reached the top of the headland, we could look down onto the Scud river and its flood plain. A pretty sight. But even nicer was a strange glow down there. Sort of yellowish. Sort of like the color that the sun makes. It dawned on us all at once: Somewhere in the area the sun was shining. We had not been foresaken.

Well, that might have been a bit too premature. We figured that we had passed the cliff bands and could start descending. There was nothing obvious in the area, like a grizzly track, and so we just went straight down. The face was steep enough that we frequently had to turn and face it to downclimb, kicking steps like we would on a snow slope. And then it got really steep. Using slide alder like we would a rope, we lowered ourselves down the mountain side slowly, until we reached a running stream. The stream fell steeply, and we had to walk through water and slippery rocks, but it seemed like it would go all the way down. After dropping a hundred vertical feet, we encountered a steep fall and it was back into the brush for more slide alder rappelling.

Lower and lower and lower we went, and finally I could see the bottom. And the river. We hadn't gone far enough and the river was still pinned against our side of the valley. Dejected, I sat on my backside and felt sorry for myself. Mike and Bob, still above me, couldn't see the river from where they were, and so just continued on. And on. And then reached the bottom and declared that I was a fool. I had seen the river, but it was my perspective that was skewed: I couldn't see the thin strip of land between the valley wall and the river. As things turned out, we came down, improbably, at exactly the first spot where the river gave way. Our route had been optimal. Even better, the sun was shining! In the below photo, you can see where we came down: On the far right side, but not yet in the trees. It is as steep as it looks.

We sat down on some logs to drink deeply and dine on raspberry fruit leather. It had been another three hour bushwhack and it was now 4 pm, 6.5 hours since leaving our campsite. Mike fired up the GPS and we played the ever popular, "Guess how far we've come?" game. We made our predictions as the GPS located satellites, munching on the raspberry leather. Who won is unimportant, but the GPS told we had come a whopping 3 kilometers, as the crow flies, from our campsite. Now, the mathematical ability of our international expedition isn't all that good, but even we could figure out that it meant that we had been covering less than 500 meters in an hour.

But, the smiles in the photos below are not staged. We really did like the raspberry leather and the sun was shining. It was shining and warm for the first time in several days. Even better, it looked like we had a clear run of several kilometers in front of us. We rested for a whole 30 minutes on the logs before putting on the suffer machines back on our backs. Mike's was nicknamed Count Porkula. I called mine Fatty, or Fatso. Bob didn't say a whole lot.

We were finally catching a break from the Land. A large, perhaps three kilometer long, island sat in the middle of the valley and the main channel of the Scud flowed on the other side of it, leaving us with pleasant meadows and gravel bars.

This didn't mean that there wasn't water to be crossed, but the small side channels were, at worst, only two feet deep. After a day of fighting the bush, we could instead concentrate on how much our shoulders hurt, about how painful our backs were.

With the lifting of the clouds and mist, we could also see something of the mountains around us, and spotted a grizzly bear high on the upper flanks to our right. Every time we had come down from the bush and were able to walk along sand bars, we saw many, many tracks. Huge grizzly bear tracks, medium grizzly bear tracks, small grizzly bear tracks. Moose and wolves and smaller four legged mammals as well. The valley was alive. Our tracks were the only rarities, and I wondered what a bear might think upon seeing them. Most likely, the bears of this valley never saw humans. A larger than normal side channel forced us into a cove filled with drift wood, where we found our first evidence of humans in a long time. A 55 gallon drum that used to hold aviation fuel. It was unclear how it got to this place, as there wasn't an airstrip anywhere close by. An open meadow on the other side could have once held something resembling an airstrip, but not for a long, long time.

We pushed through the bush on the other side and came back out into splendid meadows. Further and further they stretched, and we harbored the thought that perhaps our bushwhacking days might be over. Maybe the main channel would sit on the other side for the rest of the trip to the Scud Portage. Maybe our suffering would be over. Maybe the sun would stay out forever.

The sun was warm on us, and after so many days of rain we had a lot of gear to dry. Despite putting in a long day, we had not covered as much ground as we had hoped for, but it was time to stop. We could use the sun to dry our bags and could even build a fire to warm us. Since coming out of the bush, we had covered another 4 kilometers in barely over an hour, making our seven kilometers our total progress for the day.

We pitched the tent in the middle of an appealing meadow with a large downed tree to sit on and to dry gear on. It wasn't long before it was covered in sleeping bags, jackets, socks, and other articles. I took the lens off of my camera and set it out to dry, though the water sloshing around inside the lens didn't give me much hope for it ever functioning again.

The stove was fired up for soup and we went out in search of firewood, which was plentiful in the meadows. Large piles of driftwood sat about and we took pains to gather a massive collection of it for a fire. The fire would warm us and cheer us, and we needed some cheering up. The view back down the river was a sobering one. We could see, easily, the mountains rimming Galore Creek, and if there weren't woods and two headlands in the way, we probably could have seen our former camp.

We had not one, but two soups, making a full gallon of liquid warmth for our tired bodies. Bob built and lit the fire, which turned into an inferno that kept away the gnats and blackflies and mosquitoes. We had a first dinner, and then a second dinner, and then made up a pot of hot lemonade, and then ate two large chocolate bars as the sun sank below the mountains in the distance. Although it was pleasant outside, I was weary. After looking over the maps and making a GPS reading, we found that we still had more than 11 kilometers to reach the start of the Scud Portage, and then another three kilometers after that to make it to the banks of the Stikine, where we were to be picked up the day after tomorrow. Normally, covering that distance would be trivial, but it was longer than anything we had covered since coming off of the glacier. Moreover, we had a major river to cross tomorrow. Navo, or Navu, creek drained a big glacier and was directly in front of us, perhaps two kilometers distance. While we couldn't be stopped, we might have to get inventive to get across it, and inventiveness takes time, something we were short on.

We fired up the satellite phone, hoping to call Dan Pakula of Stikine Riversong, who was to pick us up at the Stikine. Nothing. No signal. Nada. Although the phone was on for several hours, searching for a signal, we got only got one window long enough to get a busy signal from Pakula, and for Bob to call his mother and talk for 2 minutes. Mike and Bob stayed up chatting, while I went to the comfort of my sleeping bag to try to forget about the day and to hope for a better tomorrow. If the land was like it was today, we might have to hike until the late evening in order to get out the day after. I preferred not to ponder what might happen if we failed to make our pick up, especially as the satellite phone didn't seem to work.

Alarm. The alarm. A stinking alarm. Knowing the distance we had to cover today, and knowing what the land was capable of, we actually set alarms for an early morning wake up. There was no dawdling, though we did take the time to drink down hot tea before setting out at 7:30. The sky was cloudy, but not in a threatening way and, for once, we didn't have to start our day with a nasty bushwhack. Instead, the pleasant gravel bars continued as the river was still on the other side of the island.

We came to Navu Creek within forty minutes and, though swift and thigh deep, we crossed it without incident. More gravel bars. The distance is clicking off and we're getting closer and closer. Thoughts of making the Stikine tonight and not having to go anywhere tomorrow. Six kilometers, and a few hours, into our day, we hit the first bush of the day. The island had ended and the Scud had come back to our side of the valley, forcing us into the bush. Fortunately, this wasn't a headland crossing, and we didn't have to gain any elevation. Unfortunately for us, this meant thrashing about with devils club and slide alder. Unfortunately for Mike, a slip happened and an arm, a right arm, went out for balance. Howls of pain. The bones, which had begun to set, were rebroken. We sat next to some pretty fungi while Mike recovered.

The bush didn't last long, only a mere hours worth, and we came back out onto extensive flood plains and gravel bars. We could see the Scud Portage distinctly as a gap between mountains. Maybe we would actually make it tonight. We COULD make the Stikine. We could put an end to our suffering. The Scud was on the other side, far from us. We would have sped up our pace, but the heavy packs and bruised and battered bodies kept it slow.

But the Land was not done with us, not yet. Another two kilometers went by and we were close to the end. The main channel came back and pinned against the land we were on. The only options were to take to the river, or to try to fight our way into a wall of green in front of us. Even with all the bushwhacking we had done, the river looked like the better bet. I took my pack off and waded in, staying close to the shore to use slide alder as hand holds. My scouting trip began well and the channel was only mid thigh and slow. But this lasted for only 50 meters, at which point several other channels came in and the going was too difficult. With a pack, it would have been impossible. Back I went to report to the others that we had to face the wall of green.

I found a slight opening where we might be able to scramble steeply a few meters into the heart of it. By slight I, of course, mean completely closed off.

But it was better than anywhere else and after ten minutes of fighting the slide alder, we had all managed to make it fifteen vertical feet, and 10 horizontal feet, up and onto a bench above us.

Having conquered the wall of green, we were now inside a fortress of green. Some of the densest bush yet faced us. Even the grizzlies had a tough time with this. Although we had located a grizzly track, it was clear that they passed by getting low on their bellies. We didn't have that option, and so had to fight. Devils club was the only plant other than slide alder. After thirty minutes, and making perhaps 100 meters, we came out into a clearing where an old stream bed sat. The respite was short lived, for we immediately went back into the bush for more battles with the twin horrors.

Another thirty minutes got us to a eye hole in the green where we could see that we were close to land. We popped out of the bush and onto a long sand and gravel bar that led us along to a big, stable tree that we could sit on and appreciate our situation. It looked as if we had to go back into the bush once again, but Bob was having none of it. Sans pack, he waded out into the channel, fought to a deadtree in it, and then reached a sand bar island that ran all the way to the portage. Although the water crossing was tricky with packs on, we made it over to the island and strolled the remaining distance to where we could see the portage. We were going to make the Stikine!

It was 5 pm and we had only two or three kilometers to go to get to the Stikine. And those should be easy, we thought. The Portage was where people used to carry over from the Stikine, and it that fact alone must make it easy. Perhaps it would be meadows all the way? We could hope. We ate dinner to get a little fuel for the last push, a little fuel to get us to the end of the suffering. Well, the Scud wasn't done with us. The portage was not a flower meadow walk. Almost immediately, the meadow ended and we were forced into a swamp. And then into one of the densest collections of devils club we had yet seen. The plants were head high, which meant we couldn't see our feet and falls were frequent.

We fought and fought. Why couldn't the Land just take it easy on us here at the end? As more and more devils club embedded itself in me, as we scrambled and flopped over huge expanses of deadfall, as the light grew dimmer and dimmer in our dark canopy, our moods dropped. We were making little progress and took to dodging around, hoping to find something a bit more open. And then I found it. A long, swampy lowland that, though unpleasant, was quick. We moved with a gusto, nearing the end. Sensing it. We fought across a beaver pond and through some thick slide alder through which light was streaming. This is it. We're done! I pushed out into the open and spied the river across a long flood plain. We've done it! Mike and I let out a cry of relief.

But something itched in the back of my head. I was troubled my thoughts, by a little voice in the back of my head. We had been battling for a little over an hour and it didn't feel like we had gone two or three kilometers. And worse, the mountains we were staring at, and the river in front of us, looked suspiciously familiar. "Um, Mike, could you fire up the GPS," I said sheepishly. Then it hit Mike also. Without words he turned it on and we waited for the inevitable. Bob was silent. The GPS confirmed it. We were back at the Scud. We had bled for 90 minutes in order to walk in a complete circle. We were not going to make the Stikine tonight. Our suffering would continue in the morning.

We put up the tent, in silence, where we had come out of the bush. Then I went off to a log to sit by myself. The disappointment inside of me was immense, some of the harshest, most negative feeling of my life. I had been leading out front and the mistake was mine. We had just continued to dodge left of obstructions and had ended up turning 180 degrees over the course of the 90 minutes. When I went back to the others to make dinner, they were in a similar position, though dealing with it better than I was.

We made soup and then dinner. The bugs were so bad that I had to walk in circles in order to eat in peace. My mind was so blank, I was so out of it, so mired in my own depression, that I could barely talk to Mike and Bob. I said nothing and they left me alone.

The thing that irked me the most, other than it was me that made the navigational mistake, was that we were not yet done. There would be another morning of waking up and putting on the cold, wet socks and boots. Another morning of fighting devils club and slide alder. Another day of hauling a heavy pack. More suffering. I wanted it to end, and the only way it would end was by reaching the Stikine. We were not at the Stikine, which meant the suffering would continue.

We agreed on a 5 am wake up. We had managed to contact Dan Pakula's son on the satellite phone, who told us he thought his father was going to pick us up sometime between 10 and 2 tomorrow. We would need two or three hours to reach the Stikine from here, assuming the bushwhacking was awful all the way through. Part of the reason it was so terrible today was that we were going in a circle, hitting the worst of it, and never getting above the twin horrors. I had enough in me, though just enough, to take a compass bearing of 330 degrees from the map, and to set my compass to it. We were going to take a straightline course tomorrow. I taught navigation for the Mountaineers back home, and this was just going to be a longer version of the standard end-of-course exercise for the students. We could do this. We just had to suffer a little bit more.

The last day of suffering. The last day of devils club and slide alder and the fat bastard parked on my back. We brewed the very last of the Pu-Erh tea in the blackness of the early morning. The sun had not come up. It was too early. We broke down camp and waited for it to get light enough for us to move through the thick brush of the Scud Portage. My compass, set at 330 degrees, would be our basic guide, used to walk as straight a line as possible and keep us from looping back to the Scud. At 6:10 it was time.

We pushed into the brush and across the swamp that we had come through yesterday, moving twenty meters at a time between compass checks to keep us on course. On the far side of the swamp we returned to the forest, with all of its unpleasantness. The twin horrors, of course, were as thick as they were yesterday. The devils club grew thick around downed trees, thick and high. There was little to hold onto other than devils club for scrambling over the deadfall, and progress was slow.

Mike, with his broken arm, was having some difficulty in getting up and over the deadfall and I would hear gasps of pain from behind me all too frequently. Twenty meters and check the compass. Sight in an object in front of us, and walk to it. Sight again. We would deviate from time to time to avoid the absolute worst stretches of devils club, or particularly heinous deadfalls, but tried as much as possible to keep a straight line of travel.

The land began to rise to the mini pass that formed the portage. During the Stikine Gold Rush days, this was evidently a popular place. The forest had long since reclaimed the portage. As we gained elevation gently, the twin horrors began to diminish. The forest became more open, and progress was easier. The higher we went, the better. We checked the compass less as our line of sight was longer. We topped out, perhaps 100 meters above the Scud, and traversed along the forested plateau before dropping into a devils club and deadfall choked gully, where perversely enough the slide alder actually helped: We could use it as a climbing rope to get up the other side.

Across the gully, the land was flat for a brief while before beginning a descent. The descent. As we lost elevation we had to battle for devils club and deadfall, but the sense of nearing the Stikine was becoming palpable. I scanned the forest ahead in between checks of the compass to see any signs of light coming through, any thing that might indicate that we were getting closer to the end. After shoving our way through a last bit of shrubbery, we came to a large, dead log, the other side of which held a gap in the trees. A gap large enough to look down and see a side channel of the Stikine. We sat on the log to eat and rest, satisfied that we were going to be at the end soon. We could not yet see the Stikine, as on the other side of the channel was a large island. The land dropped away sharply at our feet, leading down to just more green hell. We'd stay on the rim for a while longer. After resting, we put our packs on for, hopefully, the last time, and meandered down a grizzly trail that was running along the rim. Three hundred meters further along, we had outwalked the island and got our first view down to the mighty Stikine.

There looked to be very few places below us where a boat could pick us up, so we traversed along the rim for another half a kilometer before spying a comfortably sized gravel and sand bar below us where Dan could fetch us. A short scramble down a sandy ramp got us to the water. We were done. We had come through. Commander Mountain, in the distance, didn't give a fig that we had made it through, that our suffering was done. Mountains, like Nature, is like that. They don't care at all if you live or die. They are indifferent to the plight of individual members of a species. Nature, is concerned with life on a larger scale. Mountains care about nothing.

There was no band playing, no trumpets, no crowds to greet us. There was only us and the river and a wait of undetermined duration. It was only 8:30 and Dan's son had told us yesterday that he thought his father would get us sometime between 10 and 2, which meant we had enough time to do nothing. There was ample deadfall around us and we were still in the shade, so we built a large stack of wood, poured half a liter of white gas on top of it, and lit ourselves a little inferno. And then we began the wait.

Boots came off to be dried next to the fire. More food was consumed. I took my camera out and placed it near the fire in an attempt to dry it. Mike read. Bob snoozed. I foraged for wood. Bob foraged for wood. A massive black bear sauntered alongside the other bank, far distant. The bear was large enough not to worry too much about grizzly bears, though a big male would certainly quash him. I had never seen a black bear of his size, perhaps weighing 400-500 pounds. Most of the black bears I've encountered have been in the 150-250 pound range, but this one was a beast. An eagle flew over head. Once the bear was gone, a wolf came out, prowling about on the other bank. It was the first Bob or I had ever seen. And we waited.

After a few hours my camera began to come to life. Not everything was functioning, but another hour of gentle heat from the fire brought it to the point where I could take pictures again. Around 2 pm, two crafts were spotted, floating lazily down the river. These were our first humans since leaving Doug at Yehiniko Lake, nearly three weeks before. They seemed surprised to see us and floated over to chat for a while. They had put in at Telegraph Creek four days ago and were headed for the mouth of the Stikine at Wrangell, Alaska. The river was slow and easy they said, and they were having great times, toting beer and whiskey and plenty of food in their canoes. A beer sounded good. The roar of an engine was heard, and a boat turned a corner down stream from us and approached rapidly. It was Pakula. We wasted no time in getting loaded into the jet boat. The prospect of moving, without having to put forth any effort, of moving without having to carry the pack, of moving without having to battle devils club or slide alder or deadfall, or to go down on all fours, was intoxicating. Dan gave us some ear plugs, and off we roared in the jet boat, leaving the canoers alone once again for the remaining week of floating to the Pacific.

As we raced up the river, the three of us all had the same look on our faces. Some people reading this will know the look. Others will not. I cannot describe the look, nor can any one take a picture of it. There is a picture of me at the end of the PCT in 2003 that approximates it. I can see the look on my face, but when I've tried to describe what it means to others, it always ends in confusion.

The Stikine sped past us, gentle and easy. The thought of floating from Telegraph Creek down to Wrangell was an appealing one. No bushwhacking, plenty of fresh food, and lazy times. No crevasses or river fords or rock fall. Plenty of wildlife to be seen, rather than feared. And no Count Porkula on the back. The land we passed through was exquisite, but the price to be paid was high. A river trip would be a completely different experience, one that was taking hold of me.

An hour or so up the Stikine, a range of powerful mountains came into view. These were the Sawtooth mountains and were on the west side of the Stikine. Compared to where we had just been, these were easily accessible, though this must be understood only in relation to where we had come from. I doubted if anyone had ever been there to climb, though surely the lower reaches must have been explored by hunters.

A massive granite dome, looking like a small version of El Capitan or Half Dome, of Yosemite fame, was thrust up at one end of the range. Even with all that we had been through in the last three weeks, I am sure that all of our thoughts were focused on the very same thing at that point.

As we moved further along, the deep valley, running into a glacier and eventually a cirque, came into view and access looked better and better. Sure, there would be about a day of unpleasant bushwhacking to get in. But, what was a day? Maybe it would only be half a day. The Sawtooths were there and the boat ride from Telegraph Creek would only be about an hour or two. Maybe another time.

With the range past, the land began to become more placid. Lower. Easier. Hunting cabins and trap lines could be seen with increasing regularity along both banks of the river. We were getting closer and closer to human civilization once again. The cabins became closer together, and eventually small roads with vehicles on them could be seen. A village was passed. A second. And three hours after being picked up, we slowly rolled into the dying hamlet of Telegraph Creek. Dan pulled the boat around to a dock, slowly, smoothly. He hopped out and lashed the boat to the pier. We piled out, a little unsure of what we would do next. Dan went off to get his son to help unload some engines and canoes that he had brought up from Wrangell, leaving us to ponder what to do with ourselves for the rest of the day. Doug was coming to get us tomorrow, and it wasn't clear where we would stay until then. Anything was going to be expensive.

Dan returned with his son, a strapping young man in his early twenties, and we helped unload the boat. In addition to running river trips along the Stikine, Dan also runs a boarding house and restaurant, as we learned, solving our where-to-stay problem. The canoes and engines loaded onto the truck, Dan pulled the boat away from the dock to move it to a more convenient location. Dan's son and Mike went in the truck, and Bob and I in the car the son had driven over in, for the short ride over to the boarding house.

Although none of us had clean clothes to put on, the idea of getting a shower and removing some of the stink of the last three weeks was a powerful one. The boarding house was a three story affair with several rooms and a communal shower and kitchen at the very top. The building was historic, and many old photographs, some dating from the 1800s were in frames around the communal area. Our suffering was pretty clearly at an end, as over the next four hours we got clean, ate a salmon dinner, complete with pie and ice cream, and I drank about 12 cups of coffee. The evening was beerless, understandable given the location, but there were several videos to watch about the Stikine area. And there was a bed to sleep in. A bed with a pillow and blankets. Softness never feels so good as after an extended period of suffering. We were done.

I walked around in my thermal tights, shirtless, padding softly on the cold floor in my bare feet while drinking a cop of coffee. The others were asleep or showering again for the pure luxury of it. The cold wood of the floor was pleasant to my now clean feet, and the hot coffee, roasted in Telegraph Creek, was dark and rich, keeping my body warm in the chill of a northern morning. We didn't know when Doug was going to get us, but it probably wouldn't be until the late morning or early afternoon. There was time to do things like walk around shirtless and sockless drinking coffee.

As the early morning passed into the late morning, the restaurant below us opened up and we went down to see what there might be for breakfast. Dan's daughter had heard from Doug and told us that we had an hour before Doug might show. He would buzz the town when he got here, letting us know that it was time to go home. I drank another four cups of coffee while downing an omelet with toast and hash browns. A computer with an internet connection provided some entertainment while we waited. There seemed be a lot of waiting happening recently. There would be more to come as we faced the long drive back to Vancouver and, for me, to Lakewood. We heard the engines of a plane, Doug's plane, and went upstairs to get the last of our belongings packed. Dan's daughter drove us out to Sawmill Lake, where we found Doug's plane, but no Doug.

We loitered around the lake, battling pesky mosquitoes and black flies and gnats, wondering where Doug was, but with no particular anxiety over leaving. Once we left here, we only had a long drive to do, a long drive that was only long: It had nothing especially exciting at the end for me, especially as I still had to get to Lakewood from Vancouver. Three men were getting ready to fly into the bush for two weeks of hunting and listened to some of our stories with interest, especially when we mentioned the herds of cariboo and sheep that lived on the Arctic and Edziza plateaus. They were going elsewhere, however. With time Doug came back to town and greeted us, glad to see us all in one piece, and chuckled at Mike's broken arm, chuckling because any sane person, any of his other clients, would have retreated immediately and gotten flown out.

The weather was beginning to close in and we needed to leave. It wasn't a long flight back to Tatogga lake, but Doug needed some visibility to navigate by and we were hoping to get some good views of the Edziza Plateau and Spectrum Range as we went. The clouds were not cooperating as we gently lifted off from the lake and began to make our way back to Tatogga.

The mist and low clouds spoiled the views, but the same joy of traveling without moving was felt strongly in my chest. Kilometer after kilometer of bush passed beneath us. What would take Doug an hour to fly would have taken us weeks to traverse on foot, battling the land for every meter of progress. The calm of finishing yesterday, which followed three weeks of general tension, was giving way to silliness as we neared the end of our trip. The end being marked by returning to Mike's Element and our drive home. I was supposed to be thinking philosophically about the trip. Summarizing it. Delving into how I felt about it. Pondering if I ever wanted to do anything like it again. I was supposed to be concentrating on higher aspirations, analyzing the spectrum of my emotions and thoughts over the last three weeks. Instead, I just felt giddy.

It was raining steadily when we touched down at Tatogga Lake. All the thoughts and questions would have to wait for another time, another place, some distant future when the march of time might bring some measure of perspective to this long, difficult journey. I was too close to it now, unable to see things for what they really were, as they really were. Like a person with his face two inches from the Pacific, I couldn't see the ocean for what it really was. I was stuck looking at a single tree instead of stepping back and looking at the entire forest. Time would allow me to process things and take that step back. For now, soft cotton clothes, smelling fresh and clean, awaited me in the Element, as did a cold can of Natural Ice. It was over.