Bishop to Yosemite Valley

July 16, 2006

Morning. A hiker in town in the morning is possessed of an appetite that would shock even the most portly of Americans. It was already in the mid 80s when we walked to Earl's for a massive breakfast and a planning session. We had quickly realized that the amount of time we had before Birdie and I flew out of Reno was not enough to complete the Sierra High Route and we needed to find a way to speed up our hike. The solution was simple: Take the PCT for a ways out of Dusy Basin. Although further in miles, we could rapidly crank out some distance and cut off one of the spookiest passes on the SHR, Snow Tongue Pass.

After breakfast we went about our various chores, which for me mostly involved reading the newspaper and buying a few days of supplies to get me to Reds Meadow. There was still the issue of getting a ride back to the trailhead, but that, surely, would not be so difficult. The local gear store should do the trick. Ishmael and I asked around, but found little to go on. Being a Monday, few people were heading up into the mountains and hitching didn't sound too promising, especially given the fact that we would be leaving in the afternoon and standing by the side of the road, absorbing the full fury of the sun, would not be much fun. Returning to the motel room, I figured it out: Take the CREST bus up to Mammoth, and then the local shuttle bus up to Reds Meadow. It would solve our time problem and our transportation problem in one shot.

The others found the solution to be acceptable, though it meant hanging out in the heat of Bishop until 4 pm, when the next CREST bus to Mammoth was running. I had kin in Mammoth, though they might not be there tonight. Birdie tracked down their number at the library and we spent a pleasant enough few hours dining on the excellent Mexican food at Amigos and chatting. A fare of $5.50 each got us a spot on the empty bus and 50 minutes later were standing, watching brutal thunderstorms pound the mountains, in central Mammoth.

I tried calling my aunt and uncle, but got only an answering machine. None of us especially wanted to stay in a motel tonight, but fortunately there was a Forest Service campground almost inside of town. We threw up our respective shelters and headed back into town to catch a movie. Pirates of the Caribbean : Dead Man's Chest. A little too much flash and not enough acting, it wasn't a movie I'd watch again, but it was a welcome diversion from normal hiking life.

The streets of Mammoth were empty as we strolled back to the campsite for a late night snack and some beer. A few stars were visible, which gave me hope for good weather for the next leg of our trip. The forecast for the next few days wasn't highly positive, but neither did it look too bad. Hopefully, today's storm was only a temporary anomaly in the normally weather friendly Sierra Nevada. I stayed up well after the others had retired for the evening, reading over another newspaper and finishing off my beer. Civilians in Lebanon and Israel were dying as the IDF and Hezbollah fought. And I was out here hiking.

The turkey, avocado, and jack cheese omelet that I was eating was really something else. Whenever I go out for breakfast, it is an omelet that comes out and I've gotten quite picky of late. The Breakfast Place, across from the campground in a strip mall, was quality. The trolly wasn't running yet, so we walked down the main road to the ski depot and waited for the (free for us) shuttle bus up the mountain to the ski runs. A $7 ticket from there got us onto the (mandatory) shuttle bus to Devil's Postpile, where we would begin our hike again. The morning was clear and sunny, though the mosquitoes were definitely out in force when we stepped off the bus and began chatting with the rangers.

"2004? 2004?" I head someone call. Not quite sure what to make of it, not even sure if it was directed at me, I continued to fiddle with my pack. "You hiked in 2004, didn't you?" came the voice again. I turned to find a woman, in full hiker garb, standing by me. "I recognize the bandana," she said. I was a little unsure who she was, so she introduced herself: Donna Saufley, aka L-Rod. Donna and her husband Jeff live in Agua Dulce and, for PCT hikers, need no introduction. Everyone knows the Saufleys. Every year they open their home to PCT hikers, and every year nearly all PCT hikers at least pass through, if not staying for several days. Donna was finishing a section hike in the Sierra and recognized my bandana, which had been a gift from the class of 2002. I hiked in 2003 and introduced myself. We had corresponded a few times via the Pacific Crest Trail mailing list and I was happy to see her out hiking. We couldn't talk for long, as the shuttle bus was getting ready to leave. I still owe humanity something of an extensive debt for the kindness I received at the Saufleys in 2003.

We set out, each following their own pace, along the trail, heading for Superior Lake. Dry, dusty, viewless trail was all that was to be had for several winding miles. I entertained myself by watching the weather slowly worsen. Starting with a few white, whispy clouds, larger puffies began moving in. Pretty to look at from town, not such a good sign heading toward high mountains. The big puffies began consolidating into a large, grey mass that, by the time we reached Superior Lake, had darkened and began rumbling with thunder.

Our trail ended and we spotted Nancy Pass easily, though I didn't want to admit it. Nancy didn't look like a very friendly gal. Thunder rolled occasionally and I had no desire to go over such a pass if lightning was in the area. Ishmael and Birdie wanted to go over, but would be happy to wait it out as well. Screwing up my courage, we decided to go over right now. Nancy Pass must have been named by a bitter ex-boyfriend of hers, for there was nothing nice, fun, pleasant, or entertaining about the scree and talus scramble 800 feet up to a small break in the mountains. The view on the other side of the Minarets, however, was spectacular.

We didn't spend a lot of time loitering, however, for the storm system was on top of us and thunder was becoming more frequent. The descent from Nancy was a lot easier than the ascent thanks to plentiful, firm snow. Moving quickly, we descended and gained a thick stand of trees lower down as rain began to fall. Breaktime, anyone? We quickly strung up Birdie's tarp and the three of us huddled underneath to wait out the rain and cook some dinner. The rain was never especially heavy, but hiking in the rain isn't something I like to do if I have a choice. Rule Number 3 of Long Distance Hiking: Only a great fool leaves a dry place. By the time we finished feasting, the rain had moved on, though the grey skies were still in place. Hiking once again, we climbed snow to a minor saddle and then traversed along rock and through forest toward Minaret Lake, finding an excellent trail along the way.

The Minarets are mountains to be feared. Although beautiful, they are not inviting or otherwise tempting to climb. Mount Rainier tempts me almost everyday, but the Minarets screamed: "Go away, or I will kill you." Perhaps it was the blowing mist and slight drizzle that fell on us as we hiked toward them, but there seemed no place in the world less hospitable than the Minarets.

I did not have to climb them, however, to continue to make progress. For now, we had a solid trail to follow through the rocky landscape to Minaret Lake. Our next pass was obvious and low, looking quite easy from the safety of the lakeshore. Indeed, it was hard to even think of it as a pass, given that it was, like Knapsack, only a few hundred feet off the deck.

As we rounded the lake we came upon a beautiful campsite complete with impossibly dry ground. I put forth the idea of camping, but we still had two hours of light to play with and decided to make it up and over the pass to Cecile Lake on the other side.

We located a use trail that took us up toward the pass, where Roper told us there was an easy class 3 chute to the top. I led up, but soon realized that the use trail was not going toward the pass. Instead, it was climbing distinctly to the right of it. We stopped, all having come to the same conclusion, and pondered the landscape for a while. Finally, I decided to continue on the scrambling route we were on, making the top after a few minutes of class 2 scrambling. A snowy basin, rather than Cecile Lake, greeted me. Traversing the basin did the trick, as Cecile Lake was just on the other side of a small rise.

I called to the others and sat about to wait, watching the weather slowly clear and wondering where we might be able to camp. Cecile Lake was completely snow and rock bound and camping might be a problem. It was already 7:30, which meant that daylight would soon be leaving us. Twenty minutes passed and still no Ishmael or Birdie. I called a few more times, but heard nothing in response. Finally I saw them emerge on the other side of the basin and flagged them down. They couldn't hear my shouts, which should have been obvious to me given our respective locations. We dropped down to Cecile Lake and Ishmael pointed out the obvious thing I had failed to see: We had to keep going.

We could have found a place to camp, but the traverse around the shore of Cecile Lake was completely on rather steep snow and in the morning it would be rock hard. Remembering our difficulties coming off of Mather Pass, had to push on to at least the outlet of the lake. I kicked steps across the steep snow, trying to move as quickly as I could. Fortunately the traverse wasn't especially long and we reached the outflow safely by 8:30. Unfortunately, we didn't have much light left and the vista down to Iceberg Lake wasn't encouraging. Steep scree, talus, and snow. Without crampons, there was no way were going to try it in the morning. Iceberg Lake was hemmed in by tall mountains and was still almost completely frozen over. If we didn't go now, we'd be stuck until the sun was able to fall on the slopes, an event that would probably not happen until the afternoon.

Not having much of a choice in the matter helped motivate me, as did the lessening light, as did my general weariness and desire to be in camp. I led down the rock and out onto the snow, kicking what steps I could in the rapidly hardening snow. Several times my boots simply bounced off of ice. It was nearly 9 by the time I finished the traverse above Iceberg Lake and reached terra firma once again. Ishamel and Birdie were at least ten minutes from the end of the lake, so I scouted for campsites in dark, finding an excellent flat spot only a minute down the trail. I was able to flag them down when the reached the ground and all were very, very happy to be in camp.

Tarps quickly went up, though we could see stars poking through the remaining clouds of the storm; a good sign for the morrow. I thought about adding a forth rule for long distance hiking, something concerning walking past a great campsite, but was too tired to even try. Besides hiking should have as few rules as possible and I already had three of them.

We slept in for an extra forty minutes in the morning as a reward for the length of the previous day. Gone were clouds, back was the sun. The difficulty of the descent from Cecile Lake and the traverse above Iceberg made me glad we had hiked late yesterday.

We set off at a leisurely pace, but quickly got cliffed out and had to retreat a bit before descending into the valley holding Ediza Lake. A bit of map reading and terrain scanning showed us where Whitebark Pass was, though the route to it wasn't very clear. Roper told us to ascend to a frozen lake in a snowy bowl below Mounts Ritter and Banner, and then traverse over to the pass. It looked more efficient to head directly to the pass itself through the thin forest. Either way, however, was going to force us to cross a raging creek, a prospect none of us found enticing in the least.

A trail runs all the way to Ediza and we met with several groups of hikers. Ishmael rock hopped and then forded the river while Birdie and I looked around a bit for something a little more to our liking. We found a man in camp whose companions were on the flanks of Ritter at the moment. He pointed us downstream into a flat area where the creek was much slower. Additionally, he confirmed the wisdom of Roper's route.

We dropped down to the flats, forded and eventually linked up with Ishmael once again. The hike up the valley toward the frozen lake had a climbers path running through it, though it frequently disappeared. No matter, for route finding here was just as easy without it. The forest turned to open rock and eventually to complete snow of perfect firmness for walking: Hard enough not to posthole, soft enough for traction. As we neared the frozen lake, still out of sight, we made a hard right turn and went directly up the snow to a higher set of lakes that were also on the route.

Although circuitous, the route we had taken had the advantage of being easy and we had little elevation left to gain. The traverse over to Whitebark Pass was over solid talus and we reached it with little difficulty.

From the top of the pass a whole new world opened up for us. Thousand Island Lake sat close by, as did the mountains forming the barrier into Yosemite National Park. I remembered the area fondly from 2003. One of my happiest days on the PCT through the Sierra was when I hiked through the region, moved over Donahue Pass, and dropped down into Lyell Canyon, running all the way to Tuolumne Meadows. The lush landscape was a joy to hike through and I considered the possibility of separating from Birdie and Ishmael and pursuing my own course for a few days before linking up again in Tuolumne. Spend a day or two lounging around Thousand Island Lake, then take the PCT up and over Donahue Pass and into Tuolumne.

We lazed in the sun for nearly an hour soaking up the rays and the terrain. After yesterday none of us seemed to be in a terrible hurry to go anywhere. The big puffies were back and I could only assume that in a few hours they would consolidate into a storm, probably just as we were nearing some precarious location. It was this thought that eventually got me onto my feet for the steep snow descent down to Thousand Island Lake. I rumbled quickly down to the flats, arriving far enough in advance of the others to scrub out my socks in a local stream and eat a little more food.

Our route took us over a small saddle and then down to a land bridge separating Thousand Island Lake from a small pond. After crossing the land bridge we hiked across rolling, verdant ridges to reach a hard pounding stream coming down from the vicinity of Glacier Pass, our next destination and one of the few east-west passes on our route.

The pass could be mostly seen from the green of the valley and looked like a straightforward snow climb. I moved out at a rapid pace, trying not to look back and dwell upon the rapidly darkening skies coming toward us. As long as I kept my eyes pointed at the pass, all I could see was blue skies and a few friendly white clouds.

I couldn't help myself, however, and found my eyes drifting rearward from time to time, hoping that the sky might at least have not gotten any worse in the few minutes in between glances. Although trudging along on snow isn't the most fun thing in the world, a good, solid snow path makes for much easier walking than a jumble of rock.

I crested out on Glacier Pass thirty minutes before the others, which gave me plenty of time to find a good rock to hide from wind, which had become howling as I approached the top. The pass was rock bound, with a gorgeous, frozen lake just below it.

My time alone at the pass also gave me time to contemplate our route, which didn't sound exactly like a walk in the park. We had a complex waterfall system to navigate through before beginning a traverse over to Twin Island Lakes. The waterfall system could be easy if we found the right combination of ledge systems and the weather held, or it could be a giant pain in the arse. Ishamel and Birdie arrived and rested briefly, but one look at the weather told us not to linger for long. The descent from the pass involved an annoying talus hop, moving from boulder to boulder, hoping that none would shift and reaching out for balance when one did.

As usual, Ishmael took the lead on the rock, finding a good, mostly class 2 ledge system to move along, bypassing the sheer drops of several of the waterfalls. As we lost elevation, the ledges became more difficult, including a few class 5 moves to get down from one system to another. Turning into the rock to downclimb involves a certain amount of faith that your feet will find something to stand on, for your eyes cannot help you.

Ishmael's route went through and we got down to a snowy basin that seemed to cover a pond. The first flat ground we had stood on since beginning the climb to Glacier Pass, it would have made for an excellent resting spot had we been a month later when the snow would melt and expose a dry place to sit amongst the flowers. Or if the skies were not darkening.

We climbed out of the basin and then traversed over to a steep, mixed rock and shrub gully that we could descend with some measure of safety, following another branch of the waterfall system that we had just finished skirting. Thunder could be heard, though it sounded far enough away not to be too worrisome. Besides, the safety of trees was not far ahead and it was just about time for dinner.

In a grove, we strung up Birdie's tarp once again and began the dinner ritual. The usual meal-time silence was broken only by the suggestion of camping near by, despite the early hour. None of us wanted a repeat of the previous night, though we didn't especially want to camp where we were. No, we'll go on for another hour, which would easily get us to Twin Island Lakes, right?

Eating a hot meal and resting for an hour has a way of improving one's outlook immensely. The weather system seemed to have gotten hung up on the Minarets and the Ritter Range, where life looked extremely harsh, and it seemed we might again escape a soaking. We followed a climbers trail as it traversed high above a beautiful valley, in which we spotted a tent pitched in a sheltered bit of green grass.

The traverse was never especially difficult, but looking back at where we had come from it seemed impossible. Steep and imposing the traverse was, but our route above it looked even worse, especially with the storm raging. Our climbers trail eventually descended all the way into the valley, where we were not headed, but it had gotten us most of the way across to Twin Island Lakes and we needed only a few more minutes to reach the base of the walls that shielded the lakes from us.

We ascended the walls via a few breaks in the rock and only needed another fifteen minutes before we pushed our way through the final obstacles to the northern most lake, a scary place indeed. Sheltered from the sun, it was dark and cold, with plenty of snow left on it. However, I was not planning on swimming in it, just traversing around it. A steep, hard snow slope protected the area immediately above the lake, forcing us high onto the rock above it, scrambling class 3 terrain for a while before becoming completely cliffed out. A rope and a rappel seemed required to get down to the shore of the lake from here. There might have been a scramble route down through the rock, but as it was already 8 pm I had no desire to look. No, the snow would have to do.

We back tracked and I led out onto the snow, kicking huge steps for the others and making sure my axe was firmly planted into the slope. The snow was quickly icing over and the steepness of it meant that a slip would result in a rapid slide. We were only twenty five vertical feet above the lake. I tried not to think about how cold the water would be, or what we would do if some one did fall and slide, as they must, directly into the dark waters below. I just concentrated on kicking big steps. Toward the end we were forced low, resulting in an additional worry about breaking through the snow and into the water. The traverse took nearly half an hour of worry, but turned out to be far more pleasant than what was awaiting us.

We knew from Roper that we would have to ford the outlet of the lake, but were reassured by his description of it: Slow, solid footing, at most three feet deep. However, this was not quite the case: The outflow was significantly deeper and the water frigid. Although not fast, when you are chest deep in water it doesn't take much of a current to push you off your feet. It took some time, but eventually we re-arranged our packs and screwed up our courage. It wasn't especially wide, perhaps twenty feet, but as I watched Ishmael descending into the water, noting the presence of a long water fall just down stream, I wasn't so sure that we were making the right decision. The water rose up quickly past his knees, then to his waist. Then to his stomach. Then to his ribcage. I saw him wobble, searching for a clear path along the bottom, then right himself and forge ahead to the other side, grabbing for willows, or anything, to pull himself out of the water. We let out a cheer and moved into the water, Birdie in front and me behind. The cold of the water, as it engulfed my stomach and ribs, was shocking. I felt myself losing control just where Ishmael had, just where Birdie had a few seconds before me. I made one last push and got across, pulling myself quickly out of the frigid water, too cold to celebrate being alive.

A sandy flat area helped us to decide to camp right where we were instead of searching for the southern lake. Clothes were rapidly stripped off and exchanged for dry ones. I fired up my stove to make a pot of communal tea, getting camp together as the water came to a boil. As if in exchange for the various travails we had survived today, and the final ford, the weather began to clear and we were treated to one of the greatest sunsets I had ever seen

Thoughts of the ford vanished as the sky lit up. Thoughts of suffering died. All that remained was fascination and admiration for the simple bending of light. I fired my camera often, then put it away to watch the remainder of the show without the distraction of it, enjoying a cup of hot tea along with the show. If there was a more perfect sleeping chamber in the world, I didn't know it then.

We slept later than usual once again after the difficulties of the end of the previous day. Blue skies, perfect weather, hiking by 7:30. According to Roper, today would be easy. We had a bunch of traversing to do and then a descent into Bench Canyon.

Only one pass today, and it was supposed to be as easy as an 11,000 foot pass can be. However, it wasn't quite as simple as we thought it would be. The traverse around the southern Twin Island Lake proved easy enough, but we quickly got off route by descending into a lush, green valley instead of traversing around on less pleasant looking rock.

Although not a major error, we seemed to be moving very slowly. We couldn't yet see where we were supposed to be headed and the lack of visual confirmation slowed us significantly.

Three hours after leaving camp, we had made, perhaps, a mile of progress, though we could now see where we needed to go. A large, partially frozen lake served as a beacon, guiding our descent through snow and then up a bit of rock to a narrow saddle on the other side.

From the saddle we traversed more, making sure to stay high above Bench Canyon. A prominent dark rock guided us, as the lake had, to the proper spot to begin the descent. Looking down, we could see our route for the next few hours, which made me happy. The clouds were beginning to consolidate and I was hoping to make Blue Lake Pass before they formed into a storm.

From the rock we were also treated to a beautiful view of the Ritter Range and the waterfall descent we had made yesterday. The range had held the storm off of us, though I held out no such hope for today. We would need a little more pep than we had shown this morning.

We dropped perhaps 1,000 vertical feet into the lush head of Bench Canyon and fought our way successfully (i.e, with dry feet) across several fast creeks coming down from the valley holding Blue Lake. A nice system of granite slabs brought us up into the valley itself. Yet another idyllic Sierra locale, the valley of Blue Lake was one of those places so warm and inviting that I could imagine spending several days encamped in it, fishing and swimming, lounging and meditating.

There was no trail into it, but there was one into the lower reaches of Bench Canyon and it was not very difficult terrain to hike cross country through. As I passed by several perfect campsites, I could not help but feel a little sad at our rapid progress through the valley. But a storm was coming, and we didn't have much time left before it reached us.

The Ritter Range was beginning to blacken already, several hours earlier than it had yesterday, a sign of a stronger than normal storm. We pushed rapidly up the valley, keeping an eye on the obvious pass above us. We reached the shores of Blue Lake, immediately underneath the pass, and stopped for a quick break for food and water and a route planning session.

It looked like a notch low on the pass would give us easy access to the scree and talus slopes forming the upper portions of the pass. The storm was getting closer and flashes of lightning could be seen pounding the Ritter Range. We climbed slabs and talus up toward the notch, moving as quickly as we could, pushing ourselves to get up as fast as possible.

As we neared the notch we had see from below, it didn't look quite as easy as it had from far away. Instead, a hidden-from-below chute presented itself and it seemed a quick way to gain the upper slopes. Ishmael led the way up to it and as we approached, it began to look worse and worse. The terrain steepened considerably and we ended up having to get over several class 5 problems in order to get to the top of the chute. Instead of an easy traverse to the open slopes, we found ourselves in a snowy mini-basin, with steep walls. The storm was on us, with thunder booming, but thankfully without much direct lightning or rain. Ishmael took to difficult looking rock while Birdie and I went out onto the steep snow, zig-zagging our way up to another notch, where the three of us joined up once again. The highly sketchy terrain we had just passed through had been very unnecessary, but our concern for the storm was dictating a certain pace that didn't allow for much retreating or second guessing. Fortunately, the rest of the pass was easy and direct and we reached the top still dry, but fearing the storm.

The view north showed us how deep inside of it we were. A frozen lake below us was our next objective, but to get to it we had yet another talus field, followed by lovely snow, to pass through. Little time was spent on the pass. Thirty minutes of nervous work got us down the talus field and onto the snow rimming the lake, which we circled as quickly as possible. Just as hail began to fall, I found two massive boulders leaning on each other with a perfect crevice in between. I flagged the others over and we dove inside the sanctuary to wait out the storm. Remember Rule Number 3.

The space inside was cramped, but large enough for us not to be too uncomfortable. I took out my sleeping pad and settled in to wait out the storm. Food in belly, clothing put on, yet I was still cold. An hour passed with lighting pounding down around us, accompanied by massive roars of thunder and hail mixed with rain. We passed a second hour laughing at an account of some hikers on the SHR last September, giggling over the bits of humor they had injected into the narrative. The lightning seemed to have moved on and there was only a light drizzle when we emerged from the boulders. Very cold. I was shivering violently in the cool breeze and couldn't stand still for very long as we oriented ourselves to the mist hidden terrain. A long, open traverse through flat country to the base of a large peak, then descend a valley and locate an actual trail. Sounded simple.

I took off at a rapid pace to generate some body heat and bring my shivering under control. I looked back and paused occasionally to make sure that Ishmael and Birdie were following my route, but mostly I forged ahead. As I skirted streams and scrambled over rock, my body warmed and I could again enjoy the land we were passing through. Although I'm sure it would have been beautiful under clear skies and a warm sun, and would have preferred those conditions, the floating mist and fresh hail and snow gave the place a certain atmosphere that was intriguing. Just like a few days ago in the Minaret area, the foul weather brought more to the land than bright sunlight would have.

I was moving rapidly until I reached a large, fast moving river. A dubious looking snow bridge led the way across it, but I didn't have the energy or the drive to find a safer crossing point. I probed my way across it with my ice axe and it seemed stable enough. I reached some rocks and hopped my way across it to wait for the others. They seemed incredulous that I had come across the bridge, but my foot prints in the snow and my repeated nodding reassured them. Birdie moved out, followed directly by Ishmael. She stopped to gawk, as I had, at some really funny looking snow near the rocks. I called out to keep moving and when she did, a loud cracking sound erupted. Ishmael rapidly retreated just in time to escape the collapse of a large section of the bridge. Birdie was safe on the rocks, thankfully, and not in the water, where I feared she might end up. After looking around for a bit, Ishmael found another section of the bridge and came quickly across.

We rapidly crossed the last of the flats and began descending a drainage, hoping to hit trail as quickly as possible. I was tired and weary of hiking and mostly wanted to set up camp, eat, and crawl into my sleeping bag. The drainage was moving us away from the direction we wanted to go, curling toward the trail in a fashion that was going to increase the distance we had to hike on the trail.

It took an hour, but finally Birdie let out a yell and we stepped onto the trail. Glorious trail. Trail that would take us all the way to Tuolumne Meadows, with only one pass along the way. Although my spirits were still low, the thought of solid trail and no more sketchy passes, traverses, or other obstacles warmed me. The trail was mostly flat and led us quickly to a large overlook down into a deep valley, into which several enormous waterfalls were pouring. We descended briefly and then set up Birdie's tarp for another covered dinner. Silence as usual. The day was getting late and dinner was a quick one.

Though we could have easily camped right where we were, none of us wanted to chance a bear encounter and we pushed on. The trail was heavily switchbacked as it lost nearly a thousand feet of elevation down toward the Lyell Fork. I wasn't happy. I didn't really want to continue on in the hike from Tuolumne and was pondering what options I had when I began to hear a disturbing sound. The roar began softly, almost like a scratching. It grew louder and louder, until I could almost feel the pressure waves from it on the hairs on my chin. As we bottomed out, the source of the sound was in front of us: The Lyell Fork. Booming it was, overflowing its banks and raging. A certain death trap for anyone foolish enough to stick as much as a toe into it, I declared that there was no way I was going across it. In denial, we invented a trail running along it through the soaked woods. Water was flowing everywhere, with streams and bugs raging.

We continued along our invented trail, making up blazes on trees and foot prints in the bog. With light failing, we came to the end of navigable land. Another fork was crashing down the mountain side and fed into the Lyell Fork. We were stuck. There was nowhere to go and nowhere pleasant to camp. Birdie took control and found spots for all three of us, none of which I especially liked. Her and Ishmael set up camp as I wandered a few meters away looking for something more appealing. I ended up on slightly drier, flatter ground and set up in the dark, swatting mosquitoes as I did. It was a black way to end the day and my decision had been made. No way I was going on the SHR from Tuolumne. The last few days with the storms had not been that much fun. I looked over the map for options, quickly confirming via the map and Roper that indeed, we were supposed to cross the Lyell Fork. That wasn't going to happen anytime soon.

Munching on cookies, I plotted out another route taking us back up the hill and eventually over a high pass, though on trail, after which we could easily hike down to Yosemite Valley for a few more supplies. A couple more days of hiking would get us to Tuolumne Meadows. A long detour, but it seemed the most direct way short of try to wait for the storm-swollen Lyell Fork to drop to fordable levels. From Tuolumne I could take trail to Twin Lakes, where the SHR ended abruptly. Or, there was another possibility. The chances of it actually working were slim, but the pay off might be nice. It didn't involve any hiking, and did involve a person that I had known for less than half a day, who might or might not be around. It couldn't work, but it was intriguing. Of course, we actually had to make it to Tuolumne first and the map showed that this might not happen. We had to cross several rivers to get there, and if they were as raging as the Lyell Fork we might have to retreat yet again. Where we would retreat to, I had no idea. It was a depressing way to end the day, but the thought of tracking down La Flaca kindled some hope in me.

I wasn't especially happy in the morning, given the still raging river, swampy land, hoards of mosquitoes, and the prospect of a long detour to Yosemite Valley. Ishmael and Birdie had come up with exactly the same escape route that I had, which made decision making easy. Back up the hill we went, passing our dinner spot along the way, and reaching the top of the climb just as the skies began to break into patches of blue. We continued our retreat, passing the spot where we came out of the woods from Blue Lake Pass, and eventually gained a view of what we assumed was Red Peak Pass, our destination for the afternoon.

As we wound our way down the trail, the skies began to look better and better, but the bugs never went away. At a trail junction we met a young man with three older gentlemen in tow, apparently a guide and clients. We described part of our route, much to the guide's delight, and got some information from him on Red Peak Pass, which they had come down yesterday just before the storm hit. "You'll have some snow on the way up," he warned. An easy river ford and more bugs brought us to the base of the climb toward Red Peak. With the sun now fully out, I began to feel better and better about the rest of the hike to Yosemite Valley, especially as we had trail all the way. In fact, I even stripped off my rain gear, worn mostly for bug protection, and put on sunblock and DEET. My confidence in the weather, however, was misplaced.

The three of us became strung out on the climb toward the pass. After all, we were on trail and nobody could get lost on a solid trail like this. Moreover, there would be tracks leading us to the pass, which we had already spotted from afar. So confident were we, in fact, that no one bothered to look at the map.

Nearing the 10,000 foot mark, I found myself behind Ishmael and in front of BIrdie in a large, snowy basin below Red Peak. The pass was on the right side of the mountain and there was no sign of trail, buried, as it was, by snow. No matter, I thought. Ishmael's tracks disappeared on some rock on a short cut he was trying. I followed some slightly melted tracks higher up into the basin, then cut over myself when my feet got cold. I scrambled on rock, occasionally moving on snow, trying to get around the shoulder of the mountain to where the pass should be. As I rounded the shoulder, I heard Ishmael's voice call to me, "Do you have trail?" Not a good sign. I saw him ten feet above me on a boulder, gazing around. I continued on a bit to have a look at the pass and my spirits dropped instantly.

What we thought was the pass was definitely not it. Although we were at the height of the pass we had seen, a vertical traverse stood between us and it, and no trail led anywhere. The sky had clouded and turned black, with yet another storm marching toward us. We didn't have much time left before it reached us, with its lightning and rain, and we didn't have a trail or a pass, and Birdie was still unaccounted for. I sat down with my map and studied it, trying to figure where the pass was. It was clearly on the other side of the mountain, near the snowy basin we had left, but I hadn't seen anything that looked very appealing as a pass over there. Fortunately for us, Birdie appeared a hundred feet below us, also lost. At least all three of us had made the same wrong decision. With the storm coming, we didn't have much time to contemplate a route, so I simply set out for the snowy basin, not quite sure where the pass was but hoping that something would turn out.

Pushing my way through the snow proved to be the right idea, for I soon spotted what looked like old tracks on gap in the mountain ridge coming off the left side of Red Peak. The snow leading to it was steep, nearing 35 degrees, and I had to work hard kicking steps up it, zig-zagging my way as fast as I could. Although it wasn't raining yet, the storm was on top of us and lightning was in the area. I was happy to top out on the pass and find nothing but solid trail and little snow on the other side.

A small frozen lake sat at the bottom. If the weather had been slightly decent, this was a place I would have sat at for an hour, lounging and relaxing, soaking up the views of Yosemite and the surrounding Sierra. Instead, I gulped down some water and, when the others arrived, we set off straight down the mountainside, moving as quickly as possible. We had three miles to reach the safety of trees. A few flash-bangs hurried our pace.

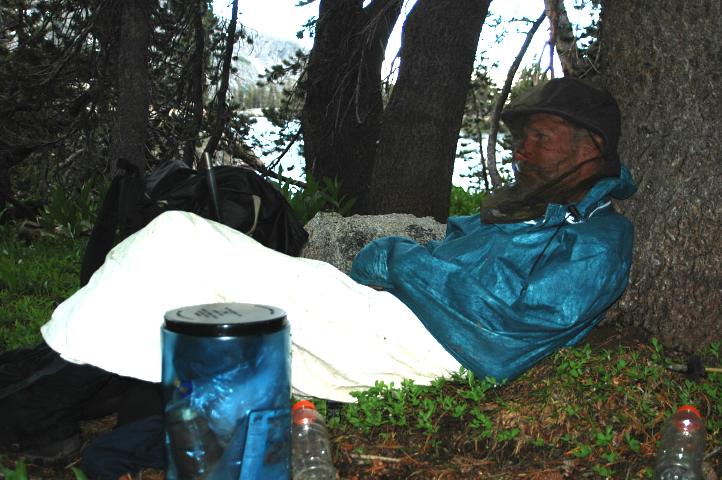

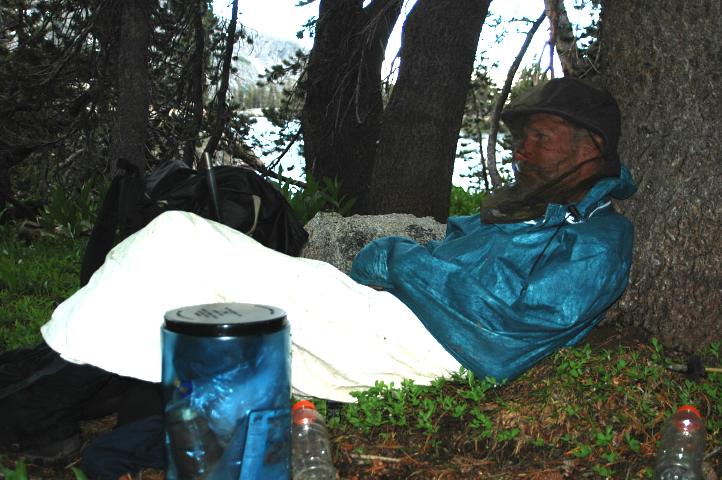

It was with great relief that we pulled into Upper Ottoway Lake, even though it was teeming with mosquitoes, all of which seemed to be driven mad by a desire to taste our blood. Light rain was falling as we got Birdie's tarp set up for a dinner break. I slathered on a heavy coating of DEET for protection, but Ishmael preferred a less toxic approach.

We were all weary of hiking and the weather. Getting lost saps a lot more strength from you that people realize and, as usual, there was little talk at dinner. All of us wanted to be away from bugs and away from bad weather. Being chased up and off passes by the storms was becoming very, very irksome. I had already seen some amazing land and felt quite content with the trip. I just had to make it to Tuolumne Meadows so that I hitch down to La Flaca, if she was even in Lee Vining. The others could hike on if they wished.

The rain had ceased and dinner was finished, which meant that it was time to find a place to call home for the night. We strolled easily down hill, jumping creeks, and passing Lower Ottoway lake in a cloud of mosquitoes. The trail began to descend down through granite slabs and boulders, meandering around and around before finally dropping us into the woods. The weather was clearing, with a lot of blue overhead and even some rays of sun.

Fifty minutes from camp, I spied a clearing on our right and Ishmael and I went over to check it out. The perfect campsite was found! A long view into the valley below, green and lush, with plenty of boulders for watching the sunset, and even a breeze to keep away the bugs. I flagged Birdie down as she walked by and settled in for the night. A more idyllic spot could not have been found and it seemed that the land was rewarding us for our travails of the last few days.

Ishmael quickly got into his tarp to rest before going to bed and Birdie, too, disappeared after some conversation. I sat for an hour on the rocks above the valley watching the world light up. This, sunset watching, is one of my favorite activities while out hiking. It requires no more energy than to keep your eyes open long enough for the sun to go down, and just a little cooperation from the weather. A few clouds in the sky to capture the light will do.

I fired away with my camera, hoping to catch something of the quality of the light, but instead recorded only some colors. Pretty colors, but not a good replica of what the place really looked like as the sun went down behind the mountains in the distance. I'd like to think that recording the true feeling of a sunset in the Sierra is not possible. I'd like to think that it is. I didn't especially care after a while, and put my camera away to just gawk. I've seen hundreds of sunsets in places scattered across the globe, from the hazy, reflective air of Kathmandu, to the hills to Tennessee, to the deserts of the Mojave and Death Valley, and even a top the rainforests of Washington. And every time I'm amazed.

Morning came far too early. I had slept deeply and wanted to sleep some more, but I also wanted to get to Yosemite Valley and enjoy the pleasures of a town stop. For Yosemite Valley is nothing, I'd been told, like an outdoor location. Rather it is a small town with a lot of trees and far too many people. I could hear Ishmael outside stretching on the rocks watching the valley light up under the first rays of the sun as I boiled water for my morning tea.

The day was clear when we started hiking down the trail, rapidly loosing elevation and, occasionally, the trail. All of us were pushing a faster pace than normal as we became imbued with town fever. The fact that we had solid trail, perhaps, was more responsible than any sort of metaphysical illness. As we dropped elevation the mosquitoes began to disappear. Snow had melted at lower elevations first, which meant that the hatch was further off down here than higher up.

Mount Starr King, one of the most outlying of the valley's monoliths, was thrust up in the distance, appearing teasingly close, yet still far away. A large granite slab gave us a warm place to rest after two hours of hiking. If we had known what the weather was going to be like, we'd have found a cooler place to rest.

Upon leaving the granite slab, the trail dropped into a burn area that gave little shade. With the lower elevation and the lack of clouds, we were hotter than we'd been since leaving the furnace of Bishop. Unlike the higher areas, water was not plentiful here and I quickly ran out, leaving me dry and thirsty for the next few miles.

Just keep moving, I told myself. One foot in front of the other, I told myself. We pushed on, moving until through the hot, stinging air, until I could barely stand it. A little shade was found for a brief rest. Brief only because we were out of water, not because we had much desire to hike on.

We finally reached the descent down toward Nevada Falls, one of the valley's most popular attractions for day hikers. Picking up water from a spring along the way, we cruised down the switchbacked, shaded trail to the falls, and what seemed about a million people. All sorts were found at the falls, which are formed by the same waters that blocked us two days ago. There were families with kids. Solo trail runners. JMT hikers. Clubs, groups, pre-teens in bathing suits. As we wandered through toward the falls, we ran into two familiar faces: Two of the Sierra Club members who had given us the ride down to Bishop. Although I would have liked to have chatted, the sun was to strong and I was too weary to say more than a few words. I retreated to the shade of some trees and collapsed in a heap to drink my water and try to recover.

I sat for an hour before putting my shoes and pack back on, knowing that I would have to go to the valley, rather than the valley coming to me. We dropped down, along with hundreds of shaky hikers, to Vernal Falls, via the aptly named Mist Trail, and eventually to the flats leading to our first road in many days. Cars were, thankfully, not allowed in this area of the valley. Two shuttle buses pulled up and were quickly jammed full. The bus driver had us, the only ones with packs, go all the way to the very back of the bus where it would be almost impossible to leave without jabbing people without our ice axes or knocking down small children with our packs. But back we went, and two exits later, we did our best to not flatten people as we squirmed our way off the bus. I was in a salty mood, given the high heat, the weariness of my body, and the number of other people, but I was as polite as I could be in asking directions to the hiker-biker campsite. Of course, rather than putting a place for people without cars in some convenient location, the campsite was rather a long walk, and not close to anything, except a small segment of the Merced River.

We found a unoccupied campsite and through our gear in the bear box, putting up only Ishmael's tarp to mark our abode before heading to the river to do laundry and take a swim. The cold, soothing water did much to remove the salt from my body and the unpleasant mood that I had been in for the last few hours. I was now ready to face the Valley again and sample the delights that it had to offer. We hopped a ride on a shuttle bus into Yosemite Village and quickly arrived at a pizza place, where I wolfed down a large pie and pint of Sierra Nevada. I would have had three more pints, but just after we ordered the place filled up with a line that stretched out the door. No matter, there was been at the camp store.

We resupplied for the day and a half to Tuolumne Meadows and stocked up on beer and treats, along with a newspaper. Just as we were ready to leave, the heavens opened up and a heavy downpour began to beat against the roof of the porch of the store. Not having a full schedule, we sat down to have a few beers and read the newspaper. The San Francisco Chronicle was filled, however, with nothing but depressing stories. The sort of stories that make one feel ashamed and awful for living a life free of bombings, murder, and general mayhem. The war between Israel and Hezbollah was raging out of control and many civilians were dying in the cross fire between the two angry parties. A student at Morehouse, who had escaped a particularly rough neighborhood in the Bay Area, had been tortured and murdered by some former students who thought he had collected a $3,000 insurance settlement. They left his dead body, carrying away only $20. A life had been snuffed out for $20. And here I was, lounging under a porch, drinking beer, caring for little else other than a dry place to wait out the rain. It just didn't seem right to me.