Syria: Damascus

December 24, 2003

Another Christmas eve that I am spending abroad. In 2001, I was in Nepal (Gorak Shep) while in '02 I was in Nicaragua (Leon). And now I will be spending Christmas eve in Syria. I was interested to see how Christmas would be celebrated in the middle east. This isn't as foolish as it sounds, as Syria has a rather large Christian minority. The muezzhin woke me at around 5 am with the call to prayer, which I listened to and then promptly fell back asleep. When I finally awoke and dressed, there was no one around for me to pay for the night's stay. I sat in the office for 45 minutes before finally leaving a 10,000 pound note, a piece of paper with my name on it, and the keys. I picked up some pastries at a local shop and wandered over to where my guidebook said the taxi stand was located. It was obviously not what I wanted, so I returned to where the mini Van dropped me off yesterday. I arrived just in time, as a mini was leaving for Chturas right away and from there I could get a service taxi to Damascus.

We roared into Chturas and I hopped out, the only one. All the others were heading for Beirut. I wandered about Chturas, which is really just a road crossing, it seems, for a few minutes, just to convince myself that I wasn't missing out on anything. I tried asking some men standing around how to get to Damascus, but my pronunciation wasn't the best and had to resort to, "Damascus?" They resorted to finger pointing and I eventually found myself standing next to a Mercedes diesel waiting for it to fill. I changed $300 into Syrian pounds and milled about for an hour before enough passengers had arrived to make the trip worthwhile. I was in the back seat, with three others, and in the front seat were the driver, and two shorter riders crammed into one seat. As had been in the case so far, I was the only tourist in the lot. The driver thundered off, pushing the diesel as hard as possible to get us up and over the hill to the border with Syria. I had to go into a special line for foreigners (Lebanese are not counted as foreigners in Syria), which held only a single Indian couple. However, they didn't have a visa and were debating various things with the border agent, who seemed terribly bored with his job. I stood in line for 30 minutes before the taxi driver stalked in, angry that he had been held up for so long (the others cleared right away). I showed the driver my visa and he waved it at the agent while barking some angry works. They exchanged some rapid Arabic and I got a form to fill out. The agent set aside the Indians, looked briefly at my visas and then waved me through.

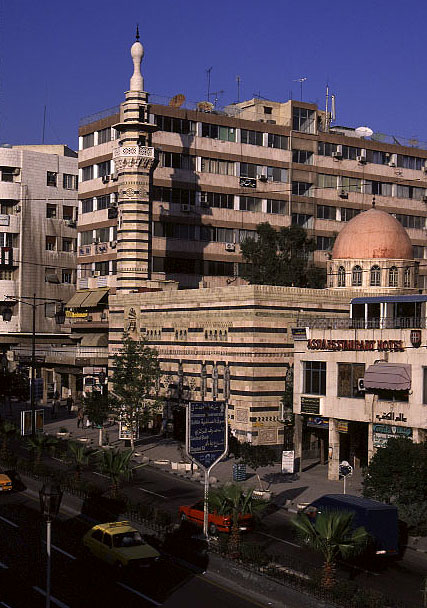

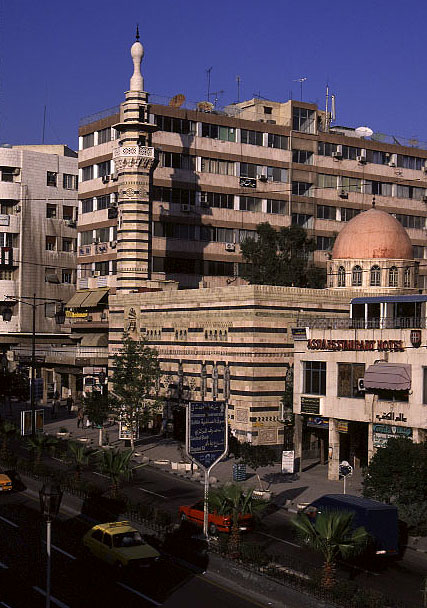

We dropped out of the cold, damp hills and down to Damascus, which seemed like a great city. Portaits of Asad, and his son Bashir (the currently ruler), were seen everywhere, and their are a few modern buildings, but mostly the town just screams antiquity. Except for one or two main thoroughfares, the streets are mostly narrow and cobblestoned, and choked with vendors and shops and madrasas (Islamic schools). The taxi driver dropped us off at one of the main taxi gathering points and I hopped out, but had no time to orient myself before another taxi driver approached me. I agreed to the $2 fare to driven five minutes to the Al Harramin hotel, where I scored a bed in a dorm room for 200 pounds, which is about $3. The Al Harramin is well located close to the old city and is inhabited by a variety of tourists from various countries, though none of them American. I was safely ensconced by 12:30 and took a short nap before heading out to the Old City, its souk (market), and the Great Umayyad mosque.

Many muezzhins broke out in the call at the same time, as there are many, many mosques in the area. These dualing muezzhins filled the air, trying, it seemed, to out do each other in a spiritual battle. But, none could compare to the muezzhin at the Great Mosque. I slipped off my shoes and left them with a doorman, whose job it seemed was to watch over the shoes of foreigners and collect a small tip in the end. I visited the tomb of Suleiman the Magnificent, under whose command the army of Islam finally conquered the unbreachable walls of Constantinople. However, Suleiman was a Turk, and the Arabs seem to dislike the Turks rather a lot. His tomb was small and rather insignificant, given his place in history.

The mosque itself was very large and consisted of a massive marble courtyard and an equally large inner sanctum. The mosque in Islamic culture is not a purely religious place. Instead, it acts as a gathering point for the community and is one of the few places in which, it seemed, men and women could gather together.

I strolled around the perimeter of the courtyard, spotting a few fellow tourists, but mostly just poking about and looking at the locals. This bothered me a little bit, however. I recalled a line from Lawrence of Arabia, in which Omar Shariff tells Peter O'toole, "...you will go back and tell them of our quaintness." This was all that I was doing. I was standing on the outside and viewing the people at the mosque as some sort of museum display, which was about as bad a way to learn about a culture as staring at a television. Because of my lack of Arabic, however, it was about all I could do and I had to content myself with watching the children playing with the flocks of pigeons that were visiting the courtyard.

Having gotten my fill of the courtyard, I went inside the inner sanctum with a little trepidation. Although Islam is a culture that really does welcome tourists, I felt a bit like I was intruding on their space. I tried to be as quiet as possible and didn't take any photos. Again, I could only play the role of an observer and could not actually participate in the culture around me. Not only was my Arabic not good enough, but I didn't have the time. Three weeks just isn't enough time to be anything other than a tourist. I returned to the courtyard to rest and look at the various artworks that hung about the hallways.

Some were intricate, others were blurred from time. Everything, however, had the air of antiquity that is so lacking in America. In the States, something is old if it dates from the 1930s. I was standing in a place that was built more than 1200 years ago.

Having gotten my fill of the mosque during the two hours I spent there, I wandered back through the souk with no particularly plan in mind for where to go. I stopped and bought a wonderful ice cream cone, which was most unlike what I was used to. The base of the ice cream was much different and had a somewhat grainy texture to it and a different flavor. Not unpleasant, just different. The ice cream was almost kneaded by hand for a few seconds and then rolled in crumbled pistachios before being set on top of a cone. A nice treat. So nice, than on a second pass through the souk I got another one. I wandered through Martyrs Square and bought a liter of Arak to celebrate Christmas Eve with and returned to the hotel for a brief nap.

I chatted with some of the other tourists in the hotel and listened to their stories from their travels. Most were on long haul tours and in were in their third or fourth month of traveling about. However, they didn't seem any more enlightened than when they had started out. Or, rather, I didn't see the look in them that thruhikers have after a long time on the trail. The long term tourists seemed that they hadn't progressed much, perhaps because they never spent much time in any one place. Or, perhaps because they always stood outside the culture in which they passed time. They had interesting stories to tell, and were hopeful for generating more in the future, but they really did seem to be just passing time, albeit in exotic places. They'd have lots of stories to tell people when they got home, but would they be any different? It was not lost upon me that I was just like them in this regard.

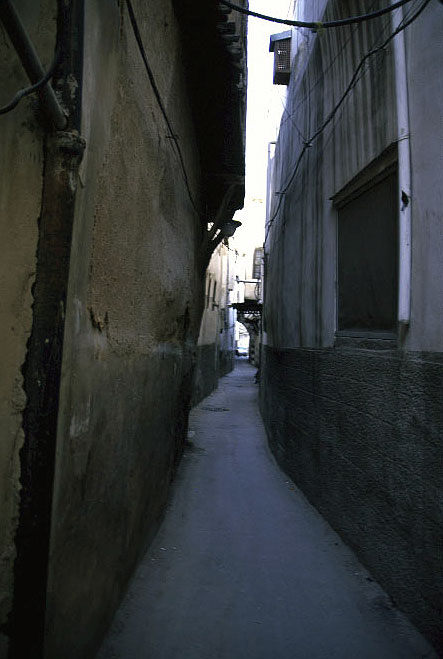

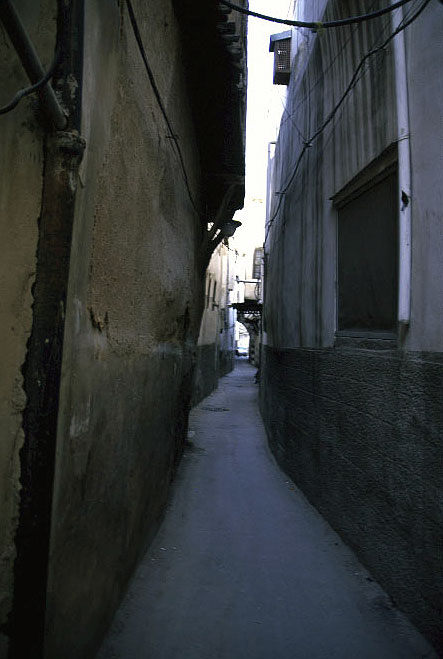

I went out for a few shwarma from various vendors along with a couple of slices of cake. I walked in the night air completely oblivious of any danger that might have been lurking in the dark alleys through which I passed. It just didn't seem worth bothering about and I couldn't have felt safer. There were many people out in the various squares and plazas, but frequently I connected them with dark pathways. I was out for about an hour before returning to Al Harramin with a quarter kilo of various pastries to savor with my Arak and more of stories from the long term travelers. Logistics, logistics, and more logistics. Flipping through the hotel's registry after tiring of the tales, there were plenty of long entries, but they were all of the informational sort. Don't stay here in Aleppo. The correct price for a seaside shack in Egypt. How to avoid be ripped off in Wadi Rum. Nothing of consequence could I extract from the writings.

On this Christmas day I awoke early and walked out to see what Damascus was like before it got too busy. The bed in the dorm at Al Harramin was the most comfortable I had ever slept in, even better than my futon back at home. There was no box spring or anything like that. Just a mattress on a wooden plank, set in an iron bed frame. First on the list of things to do was to sit around. Down the street from Al Harramin was a opening in a building with some plastic chairs out front. On my evening stroll last night the proprietor had welcomed me, but I hadn't stopped in. This morning I wanted coffee and Kemal had it. Kemal's place was a single room about 5 feet square and contained a propane stove, on which he served out cups of coffee for about a quarter a shot. Thick and strongly flavored with cardamom, they were delightful. I talked with Kemal for about a half an hour, as he spoke excellent English from his days as a student in the Sudan. His place seemed to be a local gathering point for the East African population of this area of Damascus, as when I left all the tables were full with elegantly dressed men from the Sudan and Somalia.

I picked up some more pastries from a shop around the corner and then wandered through the streets of Damascus, heading in the general direction of the national museum. In front of the museum was an outdoor display of some interesting pieces of history and I spent about an hour looking down the various rows and reading some of the displays. I sat on a bench and pondered the differences between my summer hikes and my winter travels. During the last two winters, I had spent time in a foreign land primarily as an observer of the local culture, Nepal being more of an outdoor oriented trip. An outsider, I could only glimpse upon people, I couldn't get to know them. There was no spiritual development like I had made on my Appalachian Trail section hike and the thruhike of the Pacific Crest Trail that I had completed just a few months before. While it is good to meet new people and to experience a different culture, I was also trapped into the role of a tourist. An observer. Life was more exotic abroad than at home, but I didn't have the freedom that I had back home. Not freedom in the sense of the press or expression, but rather the freedom that comes from a familiar culture and known customs. With the exception of listening to the pained, yet joyful, call of the muezzhin, nothing was stirring in my heart. Only in my eyes.

The PCT was important because of its setting, but not because it happened to be in the western United States. Had it been picked up and put down in India or Malawi, it would be have been just as spectacular and important to me. However, if Damascus was picked up and moved to, say, Des Moines, it would have lost a lot of its allure. The setting of Damascus was what made it exotic to me, not the people and the feel of it. I couldn't experience these without a stronger knowledge of Arabic and more time to work my way into the heart of the community. I sat on the bench and pondered foreign travel. I did not like the conclusions that I was coming to. The method by which I was experiencing culture was not, it seemed, one which could be, in the end, very rewarding. I was seeing interesting things and eating different food and breathing exotic air, but it was in a rather superficial way. During the summer I felt something raw and primal; something which did not depend so much on the specific location of where in the world I was. The winter trips have been location dependent. I have been, and currently was, a tourist. I didn't want to think about these things any more and so went inside the museum to look about.

The National Museum was really well done and nicely laid out, with the displays being in both Arabic and several European languages. I liked the various exhibits, ranging from pre-history all the way through the relatively recent past. Syria was one of the ends of the fabled Silk Road and had been a meeting point for many different civilizations. There was a re-creation of a synagogue and a collection of textiles that were spun from silk from China, but dated from the first to the third centuries AD in Palmyra. There was a mock-up of one of the tombs from Palmyra, which drew my interest because I would be visiting there in a few days. Very intricate gold work seemed to be where Muslim culture really shines in the world of art and there were many exquisite pieces dating back to the 10th century, and even earlier. I left the museum feeling more civilized and educated, but no more enlightened.

I left the museum a little after noon and poked around a nearby mosque that had been turned into a military museum, and then made a long, winding detour through some residential areas before stopping at a small street side vendor for a falafel sandwich and a coke, sitting among the various laborers of the neighborhood. Again, my lack of Arabic meant that all I could do was to tell people that I was a math prof from the United States and what my name was. The fact that I was from the US startled people, but in a good way. In a mixture of Arabic and English, we tried to communicate, but this was really not possible. I took a back way through the souq for another pistachio ice cream cone and then returned to the Al Harramin for a nap on the comfy bed.

After a thirty minute nap, I headed out to a different part of the souq, determined to lose myself in the streets in an attempt to get to know the culture in which I was passing time. My theory was that the tourist areas would no more showcase Syrian culture than visiting the Lincoln Monument would show off American culture. It seemed that visiting the food oriented souq would provide the best place to get away from tourists, and so I headed out, hoping that I would actually get lost and have to find my way back home through some long process.

I visited various stalls and shops to see what people in Damascus ate, what sort of vegetables and meats were for sale, and found mostly what I would have found in the US, except that the meat was generally out in the open and in a more whole form than that found in plastic packaging in the States.

As I didn't know how to ask if it was okay to take a picture, I would generally just take out my camera, point to something to the shopkeeper, and hope for a nod. Only a couple of shopkeers didn't want me to take a photo and most were very happy that I was taking some interest in them, particularly when I told them I was from America (about my only reliable complete Arabic sentence). There was even a fish stall, but only one. I found the idea of fish so far from the ocean (given the rate at which is would have to travel from Lebanon) to be a little dubious, but the fishmongers were very friendly.

I left the souq hoping to get lost, but couldn't quite do it yet. Trying to get lost means that you have some idea of where you are to begin with, but the idea was a good one anyway. I wandered about, visiting some of the mosques in the area, but eventually found myself back at the Great Mosque, despite my best intentions to visit new things.

I had arrived just in time for the muezzhin to break out into his call, and it was powerful enough to stop me where I stood. I sat on a door step and listened for a few minutes, deep in thought and feeling. I was finally able to place the sound that the muezzhin made. It was the desert. The call of the muezzhin was the sound of the desert. Not what the desert sounds like, but rather how the desert would be represented in art work. Paintings and photographs just don't seem to do the desert justice. The sparsity of large, visible attractions in barren places mitigates against the desert ever being done justice in a visual medium. The only good representations of the desert that I had come across in art were in the realm of literature. Now, however, I was hearing the desert as I sat on the doorstep. The call ended all to quickly and I was back on the street in the Old City.

I wandered through the narrow streets and eventually found the Iranian mosque that I had been looking for, but many of the faithful were filing out of it and I declined to go into the mosque itself. Rather, I contented myself by hanging around the outside walls and stopping by a fresh fruit stall near Al Harramin for a banana shake and a shwarma. I returned to Al Harramin to chat with some of my fellow tourists to see how their day had gone and what they had done. I thought mine had gone well, but I don't think that I was able to communicate particularly well the joy of walking through the food souq. Hungry again, I visited with Kemal and the East Africans and drank down a few cups of coffee while chatting with them. It was nice to be able to talk with locals in English, as I could express something more complex than my profession and my citizenship.

I made my evening stroll through the Old City for a falafel sandwich and some pastries, dodging between thick crowds in various plazas via dark, deserted pathways. Even if I couldn't join in, I wanted to see how people in the town lived and I felt perfectly safe wandering about in the dark, even if I never would have done this back at home. There was no threat here, no danger to worry about.

My first Friday in the Middle East. Friday is an important day for Muslims and most things are shut down by about 11, or so I had been told. I left for a walk in the early morning to see the Old City and found it completely empty of people. Even Kemal was closed up. Nearly every shop was closed up and only a few people were out walking or driving. While a very nice change from my previous wanderings, it felt very un-Syrian somehow. However, with no one around I could explore things that I wouldn't be able to at other times, either because the crowds were too thick or because if you stopped for any appreciable length of time, you would not be alone for long.

I walked the length of Straight Street to try to find the Jewish quarter, but got off track when I started finding old churches. Unlike the mosques, the churches were closed up tight and it didn't look like people just dropped in.

I wandered to the end of Straight Street and found Bab al Sharqi, which is an old gateway into the Old City. It wasn't terribly impressive, but it was old and nearby was St. Paul's chapel, where St. Paul was lowered over the walls of Damascus to safety.

I stalked around the outside walls for a while, looking to see what modern Damascus might look like, but mostly found old cars.

I retreated inside the old city and found the entrance to St. Paul's church quite open. I walked through the iron gate and looked around the small courtyard for a while, waiting for someone to throw me out. After the bustle of the various mosques, the church was shockingly still.

I ventured inside and sat in a few for a while, marveling at the stillness of the church. I could smell incense of some sort, and occasionally I would hear a creak, but the dominant sound was that of silence. It was so refreshing that I ended up sitting for thirty minutes, doing nothing but living in the quiet. While easily bested by the cathedrals in Leon and Tegucigalpa, St. Pauls had an intimate quality to it in this land of crowds and hustle and bustle that it made my list of favorite churches.

After I had absorbed enough stillness I walked around the grounds for a while to see if I could find anyone, but there was no one about. It seemed strange that mosques would be gathering places for the community, yet churches, despite Damascus' sizeable Christian population, did not. Having seen what there was to see, I walked to the iron gate only to find it tightly locked. A woman sat in the booth nearby, apparently the gatekeeper. She pushed a button and a buzzer rang, which seemed to be my cue to leave. I pushed the gate open and walked back out into the street. It seemed that I wasn't supposed to come into the church without permission, but there were no signs, there was no one to ask, and the gate was open. Still, I felt poorly about intruding.

I strolled out to another gate in the walls forming the Old City and found a street vendor that was offering cheese pizzas for sale. These were really just flat breads with olive oil and cheese, but they were delicious and I ate three of them on the spot. I wandered back through the Old City, taking as wildly a different route as I could, grinning occasionally at the children who peeked out of doorways at me. It seems tourists didn't come through here too often. I napped and washed clothes during the middle part of the day when nothing could be heard, not even traffic, except the call of the muezzhin. I napped for an hour before setting out to find some coffee. Kemal was open and I sat and drank down several cups with him as the city came back to life. We talked about the upcoming US elections and such things. Kemal seemed, as did other Muslims, very interested in what people in the US thought about such things. I took this as a good sign; they made the distinction between what the US government did and what the people in the country wanted. They made a distinction between what they received as news, and what was actually the case. Kemal and I talked until several well dressed Africans arrived and Kemal had other people to chat with.

I set off for the Azem Palace, which is now a sort of cultural museum. It used to house the governor of Damascus, who belonged to something of an important family. The museum had nice displays about one aspect of life in Damascus or another, but mostly I liked strolling around the various courtyards and admiring the intricate design of the buildings.

There was even a resident cat population (I saw no dogs in Damascus). Cats seem to be fairly common in the town and are well cared for. My suspicion is that they are kept around to keep the rodent population under control, and indeed I saw no mice or rats during my stay.

After an hour in the Azem palace I took another stroll in the Old City, finding that about 20-25% of the shops were now open. I walked and walked and walked some more, and rewarded myself with a delicious strawberry-banana juice. I was sitting with the juice when the muezzhin from a nearby mosque broke out in call. The haunting sound and tone of the call was so much different from the worship songs that were sung in church when I was growing up. The soulfulness and joy inherent in the call of the muezzhin is encapsulated with a direct command, "Come, be with God." This was not something that I had ever seen or experienced in a church of my own; services were solemn and serious and proper. Even the joyous songs always had a feeling of being window dressing, rather than the deep expression of joy coming straight from the soul that was embedded in the voice of the muezzhin every time he repeated, "Allahu Ahkbar." The sound that the muezzhin made was the sound of the desert, in which man might experience God directly, instead of putting on one's Sunday best and driving the Lincoln down to church, hoping all the time to get back in time for the NFL. I couldn't imagine, ever, the organist ever breaking out into tears over the music he played before services started. I couldn't imagine the muezzhin not having tears running down his face as he made the call. Sitting in the plastic chair, drinking a strawberry-banana concoction, I felt that I had gained a small bit of understanding into Islam. A very small part, but something that I had not known before.

The muezzhin finished his call to the faithful and I went in search of a snack, finding some not-so-good, overpriced kebabs and bread in a restaurant down the street from Al Harramin. Street food, definitely, in the future. I made a swing by Kemal's for a couple of cups of coffee, but found him busy with some Africans and so didn't have the chance to talk much. I realized, then, that I much prefered talking to Kemal than the other tourists staying at Al Harramin. Sufficiently charged with caffeine, I retired to the hotel for a few hours, leaving only briefly for my evening stroll in search of falafel and pastries, and called it an early night as I had big plans for tomorrow.