Syria: Aleppo, St. Simeon, Tartus

January 1, 2005

I walked out to the Al Ahlia office in the morning to catch a luxury bus to Aleppo and arrived early enough to actually have some breakfast and coffee in the little cafe next to the office. The ride along the highway was pleasant enough and only took 90 minutes, as opposed to the 2.5 hours that my guidebook listed. Consequently, I stepped off the bus in the station at Aleppo at 11:30 with plenty of time to explore around a bit before finding a room. I declined numerous taxi offers and walked down the street to find a large park in which to sit for a while and orient myself with my map. I was going to get a room at the famous Baron hotel, even though it was about 10 times as expensive as my normal lodgings. However, Lawrence had stayed here (one of his bar bills is supposed to be on display) along with Agatha Christie and other luminaries and I thought I'd spend some of my excess cash and stay in a famous place. After getting my map pointed in the right direction I walked through the park for a while, which is filled with many trees and benches and even a few fountains, along with the obligatory statue of Asad the Elder.

I left the park and passed by the Baron and was struck at how different a city Aleppo is as compared to Damascus. There is very little construction of any kind (Damascus had a lot of half done buildings) and and houses and apartments abound, all well kept up with little flower pots or beds hanging from windows or along the sidewalk. Aleppo even has traffic lights! Shops were interspersed amongst the houses and gave Aleppo a feeling of being a city, whereas Damascus seemed a lot like a village, albeit one with large buildings and heavy traffic. A light drizzle began to fall and I wandered back over to the Baron to check in and burn up some pounds.

A room was to run me $40, although I was told I could pay in pounds if I really had to, and I was shown my choice of two rooms. The hotel had obviously seen better days, but was still exquisite: High, vaulted ceilings, marble everywhere, paintings, plush chairs. After I got into my room and settled, I realized that this was a place that James Bond would stay in, although perhaps after it had gotten fancified a bit. I liked the thought. After resting for a bit, I set off for the Old City of Aleppo, With the rain, I had no desire to go to the Great Mosque and so headed directly to the souq, which is, of course, covered. While similar to the Old City souq in Damascus, there were some noticeable differences. For one, traffic is allowed in. The streets are very narrow and the shops sprawl out into the street, which is clogged with people. Even with this, small, narrow Japanese and Korean trucks and motorcycles would thread there way through the souq, although at a very low speed. Surprisingly enough, no one got hit and there were no collisions. There were even donkeys pulling carts! The Aleppo souq also had more branches coming off of it and many more caravanserais than that in Damascus. I spotted several doors into mosques or schools from the Aleppo souq, something I didn't notice in Damascus. Additionally, the vendors were more aggressive than those in Damascus, but generally wouldn't follow me for more than twenty or thirty seconds before giving up.

I came out of the souq and found that the drizzle had stopped. Directly in front of me was the citadel of Aleppo, a massive, imposing structure that exuded strength. I climbed up the stairs after paying my entrance fee and promptly ran into two Japanese tourists that had been at Al Harramin in Damascus with me. I had also seen them in Palmyra and suspect that this is a common phenomena when traveling in the developing world. Once you are in a place like Syria, everyone goes to a very similar set of attractions. Later on I also spotted three Italians that I had met in Damascus as well.

The citadel was much less imposing on the inside and was under renovation, which closed off (with ropes) some parts of it. I found a few nice passageways and even an excellent grand room, complete with roped off areas, a painted ceiling, and very ornate walls.

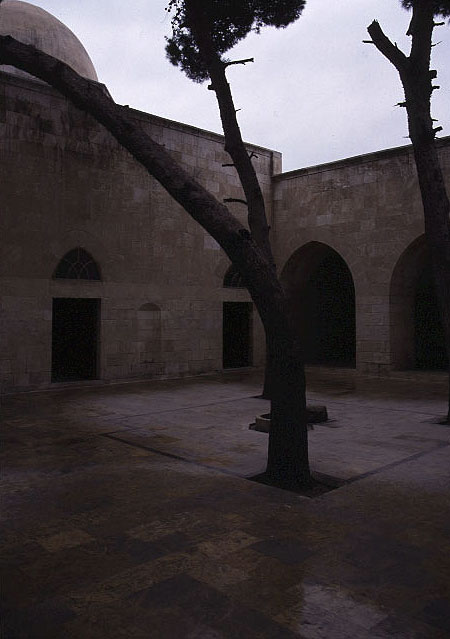

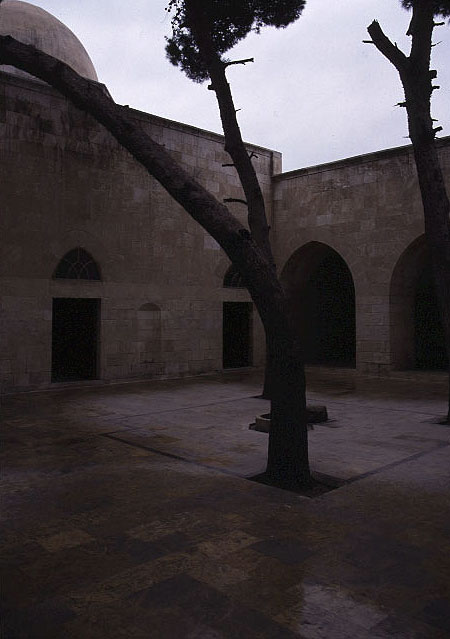

Although the grand room was nice, it was a little too pretty for my taste and I went back into the chill, damp air to climb about on some of the walls. The late hour of the day had brought many tourists into the citadel, including some large tour bus groups from Europe, whose coaches I could spot from the walls. I began to feel crowded and closed in and dropped off the walls looking for a quiet corner. Surprisingly enough, I found one. In the middle of the citadel, there was a small courtyard with a single tree in it, and no one else around.

I sat in the courtyard for half an hour and was only occasionally disturbed by someone moving through on their way to some other place. It was tranquil here and I was loathe to leave it for the more crowded walls again. However, it began to drizzle again and I was forced to seek shelter underneath the nearby passageway, where I found another place to sit and do nothing for a while.

I sat in the passageway until a large French group came through on a guided tour, which I took as a sign that I should be moving on once again. I climbed to the top of the walls once again to get a look at the Great Mosque, which was disappointingly small, at least in comparison to the Great Mosque in Damascus.

I returned through the souq, looking for things that I might buy for people back home, but didn't want to stop for too long at any one stall. Syrians are definitely fans of the hard sell, in which any prospective buyer is pounced upon immediately and taken here or there. There is no such thing as casually perusing the wares of one merchant or another. You must be prepared to constantly fend off the salesmen and retain some form of politeness. This is difficult for whiteys to do, but it has to be done nonetheless. I bought some postcards and then headed back to the Baron to write them out before dinner time. After my overly expensive meal last night in Hama, I looked for a more low key restaurant and found a pleasant one tucked away a few blocks behind the Baron and off one of the main streets. I ate down a large meal and several coffees and then went out for an evening stroll, picking up some pastries on the way back to the Baron. Even though the side streets were almost completely dark, I could sense nothing that should put me on guard or cause me to worry about being robbed. It just didn't seem like a possibility.

I sat in the bar at the Baron and had a few beers with the ghost of Lawrence before retiring to my room to read a bit and drink some arak. The Baron, for all its charm, is really a one night type place and I resolved to move on in the morning and find a place where I might meet some people other than Syrian businessmen and well heeled tourists who were slumming by coming to a place like the Baron. Plus, the water in the shower was only lukewarm.

Being a Friday, I expected to spend most of the time on foot and without too many people around. Perfect for the souq. I ate the free breakfast at the Baron, complete with Nescafe, and argued with the hotel people for a while about being able to pay in pounds. They were most unhappy about this and I ended up spending the equivalent of $48 in pounds for the night, which was more, I believe, that all that I had spent for lodging so far on the trip. It was far too early to check into Hotel Syria, right around the corner, and so I hauled my stuff with me (I don't travel with much). As expected, the souq was completely empty of people and I could look around to my heart's content without having to fend off merchants and touts. I couldn't seem to find the right way into the mosque, which I had hoped to visit early in the morning before people began to arrive for the important Friday services. I spent more than an hour in the souq before coming out of it, somewhat unexpectedly, near the citadel. I made a circuit of the citadel and amused some young boys who were playing soccer in the streets. After sitting on a bench for a while, I decided that I really had no place in particular to go today, nor any plan for doing nothing. A muezzhin from the mosque broke out into call, and I instantly had my plan: Follow the minarets and the muezzhins.

I spotted a minaret jutting up into the air and began threading my way through the small alleyways that I assumed would lead to it. The alleyways, of course, couldn't run straight and so I had to walk around and around before I reached the mosque. The alleyways held their own charm and, having reached the mosque, looked around for another minaret. Spotting one in the distance, I set out once again, completely oblivious to the direction I was going. I was hoping to get good and lost in Aleppo, and then find my way back in the afternoon.

Finding the mosque that the minaret was attached to was difficult. Being raised in the midwest, I'm used to streets being laid out in grids. Aleppo was not laid out in grids. Ergo, I would rarely find the mosque I was looking for. I walked on and on and on, finding once mosque after another, although never (no grid), the one I had set out for. Being a Friday, and not in the early morning, I didn't visit the insides of any of the mosques, but would occasionally sit outside of them and listen to the weekly sermon being given. I couldn't understand anything that was being said, but this wasn't important to me at the time. I just wanted to hear.

As I moved further and further from the Old City of Aleppo, people began to stare at me with increasing frequency. Even with all the tourists in the city, the people were not used to seeing them outside of a certain area: Bus rolls up, tourists get off and gawk, then buy stuff, then get back on the bus and are whisked away to the safety of certain hotels and restaurants. Why not just stay at home? As time rolled by I began to get hungry, but couldn't find a place that was open now that midday had arrived. I decided to head back to the Old City and get a room and rest for a while, as I had been walking for some time now and was beginning to tire. However, I had absolutely no idea where I was, which was my purpose when I set out chasing minarets. I picked what I thought might be the right direction and walked a couple of kilometers hoping that I might see something that I recognized. Nothing.I picked a new direction and walked for a couple more kilometers before ending up back at my starting point. A new direction, and a couple more kilometers. I was completely and thoroughly lost, still, and so decided to have some lunch at a felafel place that had just reopened after the main service.

My belly full, I headed out feeling better, but got turned around once again and ended up back in a spot I had left an hour earlier. I leaned against a pole and thought for a while about where to go. A man walked up to me and spoke some Arabic. Seeing my confused look, he tried something that sounded like French. I told him in Arabic that I was American, at which he smiled and switched into English. He asked me if I was here to buy firewood, which was not exactly the question I was expecting to get. I said no, which seemed to confuse him somewhat. I told him that I was a tourist out for a walk, which both clarified the situation (I wasn't a foreigner living in Aleppo) and muddied it (out for a walk? Tourist away from the Old City?). I should have asked for directions, but didn't think to do it and set off for a hill, hoping that I might spot the citadel from its moderate heights.

Indeed, I found my land mark but quickly got disoriented inside of a local souq on my way and ended up looping around a bit, emerging, with some surprise, at a large park that I had walked by yesterday. From the park it was a short walk to the Baron, and then around the corner to the Hotel Syria. For 200 pounds a night, I got a small, clean room with a comfortable bed and a sink, along with plenty of graffiti disparaging Americans, left, no doubt, by Europeans and Australians. Misspelled graffiti is always amusing. I took an hour nap and then decided to go out for another walk.

I was introduced to several Iraqis and Kurds staying at the hotel by one of the managers on my way out, and thought about the great contrast between the Baron and here, separated by a few hundred meters. I liked meeting the other inhabitants, but my Arabic was far, far too poor to have an actual conversation. I headed over to the main museum but, being a Friday, it was, predictably enough, closed. Even though I was tired, I went for a walk in the area around the souq, which is safe for strolling, but eventually got sucked into the bedlam of the market. I was weary and mostly wanted to be left alone, but this isn't done in the souq and it was my own fault for going in. Everyone wants to talk, presumably (as this is the souq), to sell me something. Some of the touts were rather inventive and went beyond the normal, "Hi, where are you from?" But, mostly I got the high pitched, "Meeeessster!" Or, young boys would rapidly fire off a string of "Alos".

I left the souq and found a shawarma vendor near the citadel where it was a little more quite and had a snack before dinner. Sitting on flower bed and eating my shawarma, I realized how alone I was in the land. This isn't like solitude in the backcountry, but rather more like isolation. My lack of Arabic meant that I could only talk with people who knew English, and they were few and far between. I can see the sights and eat the food and listen to the muezzhin, but I can't get a feel for the culture that I am moving through without being able to speak the language and, more importantly, without having more time than I did. I pondered my isolation, finished my shawarma, and headed back to the hotel to write for a while before dinner time.

The rest and another dinner at Al Kindi restored some of my flagging spirits, partly because the people in the restaurant seemed to recognize me from the night before. I even felt good enough to take an evening stroll to complete this most peripatetic day. Walking in the evenings was always a delight as the towns that I had been to do not shut down with the setting of the sun. People come out and shop, or stroll, or go to dinner, or just mill about and it is nice to be out in a crowd that is having a good time. I made a basic circuit around some of the smaller monuments and then returned to Hotel Syria, with another liter of arak and a quarter kilo of pastries under my arm. I tried some Arabic on the Iraqis sitting in the main room watching TV, but they mostly just smiled politely, as I do when someone tells me something I do not understand.

I was up at 7:30 and walked out to the mini bus depot near the souq to get a ride out to St. Simeon. I hopped a mini that whisked me out to the small farming town of Daret Azze, from which it was another 6 kilometers out to the ruins. The mini didn't run out there, but I didn't mind the prospect of walking through the countryside to get to the ruins. I had gone all of 30 meters when a lorry pulled a U-turn and came up along side me. Two gregarious young men were in the cab and offered me a ride up to the ruins for 100 pounds, which I thought rather much. I like riding in the back of trucks anyways and began to hop in back when the men waved me to come up from and jam in with them. Our foreign language skills were about comparable, but we still managed to have something of a rudimentary chat. Jameel and Muhammad worked in the area driving supplies around and wanted to know where I had visited in my travels. When I mentioned Beirut, Muhammad's face lit up and he became very excited as, to the best of my knowledge, he used to live and work there. He said that his father was an English teacher and they had lived in Lebanon for a while until Muhammad grew up and his father moved off to Saudi Arabia for work.

I felt pretty tough when I stepped out of the lorry and waved goodbye to Jameel and Muhammad, but unfortunately no one was around to see me. There were two package tour buses (the small, 15 person kind) in the parking lot, but it soon became clear that the tour companies were having a hard time bringing people into Syria. Despite the two buses, I counted about ten tourists inside the ruins themselves. The ruins of St. Simeon sit on a large hill above the plains that hold Darret Azze and all around one can see the lushness of an irrigated desert. St. Simeon was originally a man named Simon, living in the 5th century, who one day decided to hermit and a religious aesthetic. He dwelt in such an odd manner that people began to visit him to receive his blessing. Simon was not the most outgoing of people, keeping with his hermit existence, and dreaded being touched by a woman, who might transmit some temptation into him. As a result of his increasing visitors, he built himself a small pillar on which he could crouch and get away from the crowds. Finding the pillar to be too short, he built a new, larger one and chained himself to the top so that he could sleep up there without the worry of falling off. And so he passed his life sitting on top of a stone pillar. When he died, a very large church was built around his hermitage, which had already expanded to suit the needs of the pilgrims, and he was revered as a saint.

The ruined church was indeed impressive in its scope and, true to Syrian form, nothing was roped off or otherwise kept from the noisy tourists that must surely flock to this place in the spring and summer. Being winter, I only had a few people to worry about keeping out of my photos.

I walked the around the ruins for some time trying to trace out the standard form of a church and to estimate its dimensions and area. The outline of the foundation, in the shape of a cross, was clear, but one of the wings was missing. The other held something that might be called a nave by an expert, or by a fool who doesn't know his religious architecture.

For some reason I dropped my area estimation and wandered over to the what must have originally been the pilgrims quarters and later, perhaps, a place of dwelling for church goers. I scrambled up to the top of one of the walls and, perched somewhat precariously, scanned the church ruins from up high. Given the antiquity of the church, its sheer size really was impressive. I suspect that the coming of Islam brought about the abandonment of this large church in favor of more discreet ways of worship.

I walked back over to the main area to find St. Simeon's pillar now that the tour groups had shuffled off to another area. The remains of the pillar consisted of a bulbous rock on a platform. Naturally enough, people had, over the course of centuries, taken bits and pieces of the pillar and had left this little nubbin as an appropriate monument to one of Christianity's most revered aesthetics.

While the pillar wasn't much to look at, the area in which is was situated had an open view far off into the distance. Fog and clouds had come in to add ambience and texture and I sat by the pillar, with my back to it, and looked off into the distance. Without St. Simeon there, the pillar was just a funny looking rock without any real meaning or importance. But, below me I could see a work of art rendered by the natural world. Funny rock, or work of art? Which is more interesting?

I began the walk back to Darret Azze through the plowed fields wondering what the farmers think of a whitey walking along the road. I wasn't sure if they would find nothing out of the ordinary, or if they would be surprised. Most likely, they wouldn't care one way or the other. A few kilometers down the road, I found another road coming in and swung over to the right as my guidebook mentioned that there were some Roman tombs down this way called Qatoura, which is probably the name of the hamlet in which they sit. I passed a farmer using two donkeys and a wooden handled plow to break up the ground in front of his house. He was sweating heavily and seemed to be having a hard time keeping the plow in the proper position. As I was musing on how much easier it would have been with a cheaper gas tiller that you can find in any hardware store in the States, I noticed that in his yard were the relics of two old stone arches, jutting up into the air next to the uneven plow rows.

I walked a hundred more meters down the road and found the tomb, but there wasn't much to look at. They had been carved directly into the side a rocky hills and had some faint engravings left on them. I sat next to the tombs for a while before heading back toward the main road to Darret Azze. On my way past, the farmer with the arches waved me to come over. I hopped his stone wall (he didn't have a gate) and exchanged greetings before settling to the only conversation I could have with people in Arabic. The farmer used to be a solider and had only recently left the army and seemed amazed that an American was standing in his yard talking with him. He asked to see my camera which I produced and showed him how to operate. He brought his two kids out and introduced them to the funny American. The building across the street from his farm was the local mosque and the muezzhin began his call. Through various gestures and bits of English and Arabic, the farmer wanted to know if I understood what was happening. I recited the first couple of lines from the call and the farmer smiled at this. I took out my guidebook to show him some places I had been, and he surprised me by being able to read (although perhaps not understand) some of the descriptions. I thought this rather impressive and the whole episode proved to be rather amusing as I tried to explain (pantomine) some words like "reclining" and "tomb". More difficult were words like "which" and "some."

The muezzhin had finished and two men from the mosque came across the street to see what all the excitement was about. The elder one was the muezzhin himself and was adamant that I could not be American. Thinking I had mispronounced some words, I tried a few more times to tell him that I was American and taught math. He shook his head and scowled a little bit. The farmer shot off some rapid Arabic, in which I could hear the words for American and teacher. The muezzhin seemed to accept this, although he didn't seem to like it very much. He didn't have the same warmth as others I had met, but I reflected upon what might happen if a Syrian, speaking almost no English, showed up to look at a Baptist church in, say, rural Alabama, taking lots of photos as he went. The muezzhin warmed up slightly before I said my goodbyes and hopped the rock wall to return to Darret Azze.

Upon returning to Aleppo, I realized that I had not eaten all day and it was already the middle of the afternoon. Next to the mini bus depot I found a felafel shack and the second best (only to a place in Hama) sandwich of the trip: Plenty of sauce, jumbo sized, and with curiously potent pickles. I sat and ate in peace and quiet, despite the fact that one entrance to the souq was just twenty meters away. Had I been in the souq, I would have been hounded. It seems that the souq is where the hard sell goes on. Outside of the souq, the rules are different. I made sure to remember this.

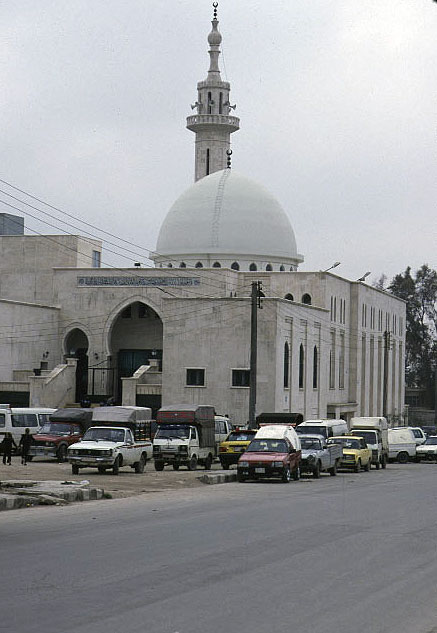

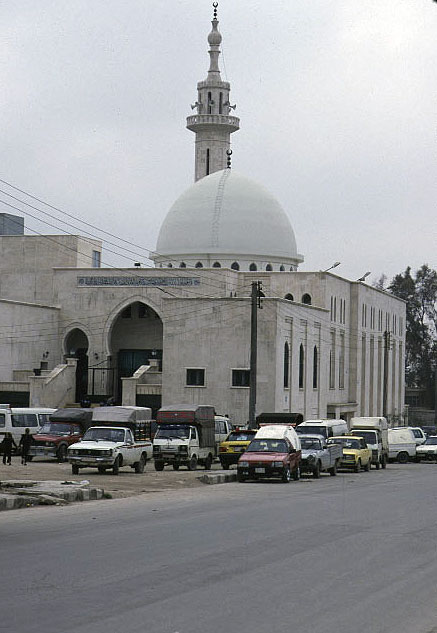

After an hours nap back at Hotel Syria, I went out for another walk, as I wanted to check out a mosque that was being built near the luxury bus station. I had spotted this new building when I first arrived in Aleppo and it seemed to be outrageously large. The workers had left for the day and I was able to perform a full circumambulation of the mosque and poke around a bit in some of the more finished sections. I braved the souq once again because, despite the annoyances, it was a fascinating place and I had not yet gotten my fill of it. Perhaps part of its interest is that we have nothing even remotely comparably to it in the US. I almost ran into an old man pushing a large cart holding pastries that I had never seen before. Using cream in pastries is a rarity, and this man had a big platter of a moist cake-like substance with a thick dollop of something dairy looking. I bought two of the pieces for the princely sum of 50 pounds. Each piece was massive and I could literally feel the sugar flowing through my blood after I wolfed them down. As I ate I noticed that none of the touts brought their sales pitch to me. But, once I finished, they were back on. I got moving again and decided to test a new theory. I bought a felafel sandwich in the souq and stood around eating it. Again, the touts were elsewhere. Merchants waved from their stores, but while I was eating, no one bothered me.

Thoroughly stuffed from the two huge pastries and the felafel, I waddled back to the Hotel Syria, said hello to the Iraqis and flopped over onto the bed with a swollen stomach. As tomorrow was to be a Sunday, I plotted out a tour route of some of Aleppo's churches to try to take my mind off of my full stomach, knowing full well that I would never be able to follow such a route: There were always things to sway my interest and streets were never as clearly marked as on my maps. I drank a few glasses of arak, for digestive purposes, and went to sleep pondering what might happen tomorrow. Where will tomorrow's farmer be?

I slept until the late hour of 8:30 and then went out to mail the postcards I had written out while at the Baron. Finding the correct postoffice was more difficult than I had imagined, as there seem to be three separate post offices, located next to each other by a school. The young boys out front of the school ignored me when I passed, which seemed rather odd as most young children like to show off their command of English when I came near them. The first post office was, I found out after standing in line for twenty minutes, devoted to the processing of lottery ticket vendors. The second post office was for packages. The third was the winner and I was finally able to send out my postcards, which wouldn't arrive until after I had returned home.

I wandered through the National Museum for a few hours looking intensely at the exhibits and found them to be superior to the fine ones in Damascus, although that one had better displays of Islamic heritage. The Aleppo museum had an extensive display about the very early history of the area, including a fascinating display of the oldest, intact neanderthal child (in the area, I suppose). Loads of good information, in English as well as other languages, guided me through the museum, which was arranged in chronological order. One stunning room was filled with carvings, statues, and relief work done in black rock (presumably basalt). Adjoining it was a room that held some obsidian spear and arrow points, but there was no information as to the source of the volcanic glass. I didn't see any such pieces in Damascus or Palmyra and hadn't noticed much in the way of volcanic terrain on the ride in from Hama.

Feeling cultured, I walked, far out of my way, to go to the good felafel joint next to the mini-bus depot for some lunch and then to the market to get a sackful of tangerines. After lunching, I returned to the Hotel Syria to pick up my camera and set off on my walking tour of the churches of Aleppo. I had hoped that I might arrive as services were ending, but I underestimated the duration of the services in Aleppo. As expected, I got lost and turned around, but eventually found the Maronite and the Greek Orthodox churches. I didn't go inside as the services were still going on, and silently berated myself for not attending services. I never go to church services at home (except occasionally on Easter or Christmas), but realized that I had missed an opportunity here in Syria, just as I had the previous winter in Nicaragua.

Still, I was able to walk around the exteriors of the buildings and explore a little bit. The churches were quiet affairs and difficult to discern unless you knew what you were looking for. As I didn't know these things, I stumbled around, missing turns and alleyways and eventually ended up in a meat souq. I was still looking for an Armenian orphanage that was marked on my map and wanted to find it before going back to the hotel to rest. I wandered around and around and around and still couldn't find it. I was beginning to think that my map was incorrectly marked when, after passing through an archway, I spotted a cross on a small, slightly recessed door and realized that this must indeed be the orphanage. I stood about wondering if I should go in, when a cloaked woman and two small children came out and walked down the street. Realizing that my only reason to go in was to gawk and be a tourist, I left and went for shawarma instead of being of touron.

I returned to the Hotel Syria to drop off my camera and take a nap before braving the souq to buy souvenirs for people back home. The souq was filled with people today, including tour groups, and thus I stood out less and drew less attention. Many of the same touts that I had run into on previous days came up to me again, their sales pitch unwavering. The basic outline is as follows, and takes place while I continue to walk down the souq.

Tout: "Alo, Alo, Alo!"

Me (walking on): "Uh, hi."

Tout: "Alo mussior [monsieur], where are you from?" (Tout puts out his hand.)

Me (shake his hand, try to get it back): "Uh, America."

Tout: "Wow! [honestly surprised] It is my dream to go to San Francicso."

Me: "Great, it is a nice place."

Tout: "You play basketball?"

Me: "No."

Tout: "Where you from America?"

Me: "Uh, Chicago."

Tout: "I love Chicago. Play basket."

Me: "Super."

Tout: "Come look at my uncle's shop."

Me: "La, la, la [no, no, no]. Shukran [thanks]."

Tout: "Okee dokee."

This all takes place in the span of about 30 seconds, at which point I'm far enough from Uncle's shop that the tout goes back in search of other tourists. The only variations are that sometimes San Francisco is replaced by Boston, New York, or Los Angeles and occasionally I'm asked if I'm French (then German, then Russian, then Australian, after which I tell them I am American). I traversed the souq to the opposite end where there was a quieter, more subdued handicraft market (more official than the souq, but also more peaceful). While I usually try to avoid officially designated vendors, the handicraft market was peaceful and some of the artists were actually there working on various pieces. I found a stall run by a teenage boy and he took me in and made me some tea while he showed me some tablecloths. I spent forty minutes with him and ended up buying three nice ones of various sizes. This isn't as simple as it sounds. He showed me many pieces and described some of the process to me and I kept mental notes of the ones I liked. Eventually I settled on one and asked the price. Then the bartering began and a price was agreed upon, though more than I indicated I wanted to spend. This is normal, as both buyer and seller have to pretend that they are paying or selling for too much or too little. Of course, I didn't want just one tablecloth and the teenager almost certainly knew it. As I prepared my stuff to go, I pointed out another tablecloth that I had noticed earlier and said how nice it was. He brought this out and I lamented the fact that I had such little money to spend, already having bought a more expensive tablecloth than I had meant to (it was helpful that the teen spoke passable English). The teen knew, quite clearly, that I wanted the tablecloth and so offered me both for just a little more than for the first by itself. We haggled a bit and then agreed, and drank another cup of tea. Now, repeat the process for the third tablecloth. In the end, I got the three tablecloths for what I thought was a reasonable price, and the teen made a sale for what he thought was a reasonable price. We drank a last cup of tea together and then he wrapped up the tablecloths for me and I went on my way.

I walked back through the souq and bought some olive oil soap along the way for more gifts. Today was my last full day in Aleppo and I waved goodbye to the souq with a mixture of sadness and joy. It was definitely the most annoying place I had visited in Syria or Lebanon, but it was also endlessly interesting. I had another large meal at Al Kindi and took a final stroll through the evening. Aleppo had been an interesting place and might make for a good city in which to spend an extended time period teaching math or working for an NGO. My Arabic would have to get exponentially better, but that was just a matter of time and effort and wasn't a large problem if the desire was there. I declined to add my own graffiti to the walls of my room and instead spent the evening reading and drinking some arak, waiting for the muezzhin's final call for the day.

Today is moving day. I checked out of the Hotel Syria in the early morning and made my way over to the luxury bus station near the mosque building site and bought a ticket to Tartous (Tortosa) on Al Qadmous, one of the main companies. My bus didn't leave for 90 minutes so I bought a few plastic cups of coffee and had a seat on a bench to wait it out. After the shoeshine boys realized that they couldn't polish my running shoes, they left me alone. I was promptly joined by two young Syrians, one of which bore a surreal resemblance to John Travolta, including the heavily dimpled chin. They spoke English well and we were soon ensconced in conversation about where I had been and where I was going, what America was like, and why I had a beard. Most Syrians, and Lebanese, particularly the younger ones, are clean shaven, though many wear a neatly trimmed moustache. This took me a while to explain as I didn't want to admit to laziness or the fact that after the PCT my face was so bronzed that shaving off my beard would look ridiculous. Travolta passed out some cookies to me and to some of the shine boys, as well as to some of the heavily cloaked women around us. Travolta, and his friend, were in the military but on leave for the next week or so and were going to visit some relatives in Lattakia.

When the subject of food came up I said how happy I had been eating in Syria, but made the mistake of mentioning arak, which brought forth a good hearted, mini lecture from Travolta on how bad it was for you. He pointed out some Kurds among the shine boys and contrasted them with the Arabs among them. Travolta thought that the Kurds were a major problem for Syria, along with the Palestinians, something I had heard from others in Syria. The Kurds are dirty and treacherous and commit many crimes, he said. They live like animals and should get out. The same went for Palestinian refugees. The Kurds among the shine boys were dressed much worse and did seem to have a worse lot that the Arab boys, and they had very distinct facial features which made them easy to pick out of crowd. As Travolta was speaking, I thought about all the different times in history (and the present day) that I had heard one group speak of another in such terms. Much of the animosity has to do with differences in economic opportunities. The Kurds and the Palestinians just didn't have many, and that led, directly, to a lower standard of living for them. I didn't want to ask Travolta what he thought of this, especially after he got a shine from a Kurd and then didn't pay him, except for a cookie. Our time together passed far too rapidly and I was sad to see Travolta and his friend go. They were my first real contact with others since Emily back in Hama.

The 3.5 hour bus ride to Tartous, which is on the thin strip of coast that Syria owns, was very comfortable and I proclaimed Al Qadmous to be superior in every way to Greyhound. The weather slowly warmed from the 40s and 50s I was used to Aleppo to a more salubrious one in the mid 60s. The Mediterranean appeared as we began to roll through town. I hopped off at the first stop, which was not the main terminal. I did so partly out of ignorance, but also because I was tired of sitting around. This wasn't the swiftest of ideas, as I needed to find the bus terminal anyways in order to get a ride to Tripoli, across the border, tomorrow. I walked down the street for a bit and then found what looked like the main mini-bus depot. After convincing several taxi drivers that I didn't want a ride I finally found the Karnak office (it was right next door, but I didn't spot it) and was told that there were several buses a day to Tripoli, not just the one at 7:15 that my guidebook mentioned. In fact, there are buses at 7, 8, 9, and 11.

Having completed my only chore for the day, I walked down toward the sea and found Hotel Daniel, one of the few budget places to stay in town. Unfortunately, all they had left was a triple, and they wanted 500 pounds for that. Not really wanting to pay so much, I walked out to the water, another two blocks, and sat and watched the waves come in for a while. I wasn't too worried about finding a place to stay and was sure something would come up.

There is something about the sea that is powerful beyond just the constant motion. The unlimited horizon brings forth hope and thoughts of the Beyond. Sitting on the eastern shore of the Mediterranean and looking west, I was staring out to my home and to what was the future of the world in the 15th century. Oddly enough, I chuckled, I was now looking into the past, into what was already known. The Future and the Past comingled together in one simple metaphysical body.

I walked around looking for another cheap place listed in my guidebook but had a hard time finding it. Eventually the owner of a grocery store that I had passed several times waved me over and asked if I was looking for a place to stay. He, it turned out, was also the owner of the hotel, but it was all full. He gave me some places to look out, but they were a bit further out from the sea and I now liked the idea of being close to the shoreline. I returned to Hotel Daniel and paid the 500 pounds, leaving me with about 600 pounds to buy dinner, some drinks, and a ticket to Tripoli with something left in reserve. I dropped my stuff in my room and took my camera with me for a stroll as the sun began to set.

Tartous appears to be something of tourist town, but is much more laid back than that designation, at least at this time of the year. Lattakia is the main town on the coast, which is why I chose to come here instead. It is also the first town that I've seen women moving about without a full veil. In fact, the women dress in a very western style, although without barred bellies and with far, far, far too much make up. The liberalizing influence of the water, I suppose.

The Old City of Tartous (a former Crusader town) isn't very large and I didn't have to walk far to see it all. A church here or there, a mosque on the corner, some felafel vendors. The one museum in town was closed for the day, but I wasn't particularly in the mood for more antiquities.

The attraction of Tartous was Tartous itself and the Mediterranean. It would make a great stop for a few days on a longer trip. A recharge, if you will. I was leaving tomorrow, but I wasn't too happy about only having part of a day to walk around. I would have liked to have walked down the coast line for a while, but light was already waning.

A long stone seawall jutted out into the sea and I strolled out along its length, having to take to the wall's top to get out to the very end. A few others were around and followed me lead, but soon got sprayed with saltwater with the crashing of the waves and retreated. I didn't mind getting some salt water on me and so sat and watched the sun go down over the sea. The sun dipped closer and closer to the water and the land began to glow with the purple and orange that happens everywhere in the world. Watching the sunset, it didn't matter that I was in Syria and that this was the Mediterranean. I could have been in Florida watching the sun set over the Caribbean. I could have been in Namibia watching it set over the Atlantic. There was something universal, crosscultural, about what I was watching and that gave me hope for mankind through the words of poets and the brushes of painters.

The sunset and I had a few minutes of usable light left to get off the sea wall and to find some dinner. Near the main square I went into one of the many chicken joints and had a seat at a plastic table. An enthusiastic owner tossed a half chicken onto a grill and basted it with some sort of buttery-garlic sauce before setting it in front of me, along with a huge stack of bread, pickles, hummus, and a cola. The chicken was, by far, the best that I had ever had, anywhere. Unlike chicken in the States, it actually tasted like something and was cooked and seasoned to perfection. Also unlike US chicken, it wasn't dry, stringy, or otherwise unpleasant in texture. I very rarely eat chicken in the US, but if people could get birds like this, and cook them similarly, I'd eat it all the time. As is, I'd rather have tofu in the US, as it carries more flavor, is juicier, and more succulent than the dry, boring, pallid boneless-skinless chicken breasts that so dominate. I ate it all down, checking the bones for any scrap of meat that I had missed on my first pass, and then licking my fingers with something akin to delight. The owner seemed pleased at my reaction to his cooking.

I made a swing by the liquor store for a half liter of arak but, much to my surprise, couldn't locate a pastry shop. This is probably a good thing as all the arak and pastries have certainly been building on my waistline. I retired to the Hotel Daniel and opened the window full to let in the sea breezes. The street eventually quieted down and, before going to bed, I stood out on the balcony smelling the air and thinking over what Syria had been like; what it meant to me and how successful the trip had been. Doing such a thing during a trip is never fair, but I did so anyways knowing that in a few months I would feel differently. The main point that kept coming back into my head was my lack of Arabic and my lack of time. I would need both to be able to grasp, in any meaningful way, the culture I was in. Time, thanks to my government, might become scarce in the future. I slept fitfully.