Three Fools Tilt with Windmills

Three Fools Tilt with Windmills

Lakewood to Puente del Inca

December 12, 2008

I sat and looked at the pile of gear that covered my apartment floor, shaking my head at the monstrosity of it. Plastic boots with high altitude liners. Approach boots. Approach pack. Large pack. Ice axe. Crampons. Four pairs of socks. Hardshell jacket and pants. Down parka. Insulated pants. Four hats. Three pairs of gloves. Sunglasses. Goggles. -30 degree sleeping bag. Two sleeping pads.

Next to the gear pile was the food pile. Eighteen days of food packed into gallon ziplocks dutifully marked with whether it was a rest day pack, climbing day pack, or summit day pack. On a piece of paper I had the exact caloric contents of each bag jotted down. I took a long drink on the glass of homebrew that I had been sipping and shook my head again. I had walked nearly a thousand miles from the Rockies to the Pacific just a few months earlier with a few pounds of gear and a fistful of maps. What was I doing?

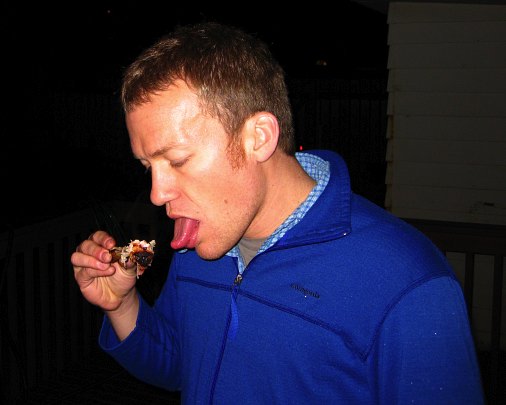

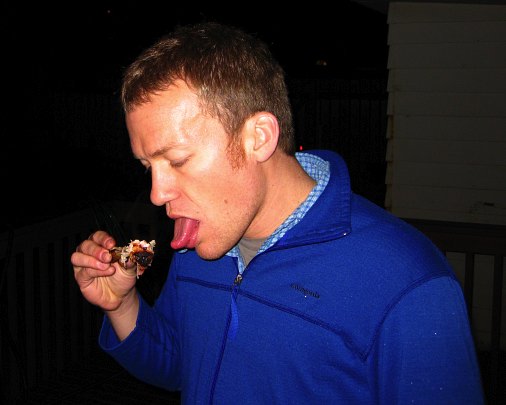

Every story needs a proper beginning, but sometimes the start isn't it. This is the story of three friends who went to the other side of the world to tilt at windmills and managed to come back alive, healthy, and still friends. It is the story of a journey to the roof of the Western Hemisphere. It is a story with beautiful women, Swedish screwdrivers, and a dancing German who doesn't like beer. Let us begin with the main characters. Below is Wayne aka The Great Destroyer, who shall eventually be known by his Argentine nickname of Winey, pronounced Wine-E. As you can see he is a handsome man who likes his chicken and isn't afraid to smile.

Winey and I have climbed a lot together along with Kevin, who somehow got tagged with the nickname of K-dizzle, perhaps due to his gangsta lifestyle and ghetto upbringing in P-town, otherwise known as the Suburban Hell That is Puyallup. To humanize him a bit more, I'll reveal that K-dizzle hadn't had chicken before we cooked up a mess of it at Winey's place a few days before this story was supposed to start. And me? Well, I'm writing this and can keep any embarrassing pictures of me out of the story. Besides, all that you need to know is that I'm handsome, intelligent, and stunningly awesome.

The morning after our story was supposed to begin was dark and grey, with a storm coming that would eventually shut down the Puget Sound area for days on end. Three of us were running away to where it was warm and sunny, leaving winter for summer, northern hemisphere for southern, Polaris for the Southern Cross. Kevin had gotten on a plane two days earlier so that he could sit for many, many hours in multiple airports across. Wayne and I had a much more civilized, though still lengthy, flight from Seattle to Atlanta to Santiago, Chile to Mendoza Argentina. A wee 20 hours of travel. Assisting us was Vanessa, also known as Gremlin's Mom, though for reasons which I can't quite bring myself to put out into posterity (lest the Gremlin some day read them).

Gremlin's Mom gave us a ride to the airport before heading out to do some Christmas shopping, which greatly eased the start of our journey. Wayne and I each had a carry on bag and we had five large, heavy duffle bags of gear that we were hauling down to the other side of the world. It would have been very uncomfortable trying to move that gear on a bus. GM dropped us at the curb and after a short goodbye, left us to fend for ourselves.

Airports are not the most fun place in the world and flying is one of the least pleasant things you can do these days. It didn't always used to be this way. Flights used to be fun and exotic. You got something to eat. The staff was nice. Security didn't stick a metal detector into your underwear. But all that has changed and now TSA, the airline staff, and the airport vendors are given special training into making your experience as unpleasant as possible. Our airline, who shall remain anonymous (Delta), was so neutral in their approach that their lack of hostility actually seemed like courtesy. But nothing can make 20 hours of riding in three different metal tubes remotely comfortable. If I had a liter of Jack I might be able to pretend to be happy, but TSA took that, and my stash of Vicodin, leaving me with only a Sozhenitsyn novel and a year of - soon to be fulfilled - expectations for company.

I breathed deep the open air outside of the Mendoza airport and relished the dryness. The sun was hot, not warm, on my fishbelly skin and I could feel the cancer cells growing as I smiled. It wasn't just the dryness or the heat or the sun or the relief at being on the ground after being caged up for so long in the confines of secure areas, it wasn't just these things that made me so happy. I looked at Wayne as we got into the natural gas powered taxi and saw the same thing. The mundane world was gone and we were on our own. We could make it what we wanted it to be and didn't have the constraints of habit to weigh us down. We managed to communicate with the taxi driver where we wanted to go and fifteen minutes later rolled up in front of the Hotel Conlfuenzia on a shady, tree lined street.

Kevin was out, and with him the key to the room he had gotten for us, but there was cold beer in the fridge and the smallest size was a liter. We got two for the equivalent of $1.50 each. Although it was twice the rate we'd find in the grocery store, I was happy to pay 75 cents not to walk down the street. Kevin returned after thirty minutes and, re-united once again, we checked over our gear to make sure nothing critical had gotten broken or gone missing on the long flight down. The room was spacious and comfortable, with three beds and a large window overlooking the street. Our own bathroom was just down the hall and we were paying the equivalent of about $15 each per night. It didn't take me long to start liking Mendoza.

Wayne and I had eaten nothing but airline food since leaving Seattle and needed to feed. After finishing our beers were headed out into the hot afternoon sun to find some of the steaks that Argentina and Mendoza are so famous for. The city itself sits on the 32nd parallel in the southern hemisphere, which makes it about equivalent to San Diego in terms of distance from the equator. Lots of sun could make for an unpleasant city experience, like being in Los Angeles, but many years ago the city planners decided to plant trees everywhere in the central part of town. Trees lined every street, giving shade and cooling the air to the point where it was comfortable to move about, even if most people were resting. The planners did more, however. In a move indicative of cultural enlightenment, they built parks and plazas around the city for people to gather and congregate in.

We visited one of these, the Plaza de San Martin, on our way to eat a late lunch. The plaza was big enough to afford lovers some privacy and to give kids a place to run around without getting in anyone's way. In the center was a large statue of General Jose de San Martin, who is a sort of George Washington for the Southern Cone countries of Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay. It would be better to call him a southern version of Simon Bolivar, but most Americans are more familiar with the good ol' George. As I grow older and more crotchety, I find I like public spaces more and more enjoyable and necessary. I like it when people come together in the open air and share time. The fact that Mendoza had many plazas and parks made me like it all the more. I had only been on the ground a few hours and I was already in love with the place.

We walked around for a bit before finding a main strip of outdoor restaurants that seemed nice enough. Although none of us spoke much Spanish, trying to communicate with the waitress was fun and easy, even if my pronunciation of lomo a la pimienta sounded as bad to her as it did to me. We ordered three liters of beer, which was a bit easier to do, to chase away the heat of the day.

The steak was excellent even if the beer wasn't so good as before. We lounged at the table, not in a hurry to go anywhere in particular, and talked about the trip and what we needed to do tomorrow. Kevin had bought all the white gas we needed, leaving us only two chores for tomorrow: Get a permit for the climb and somehow get to Puente del Inca, the town closest to the trailhead we needed.

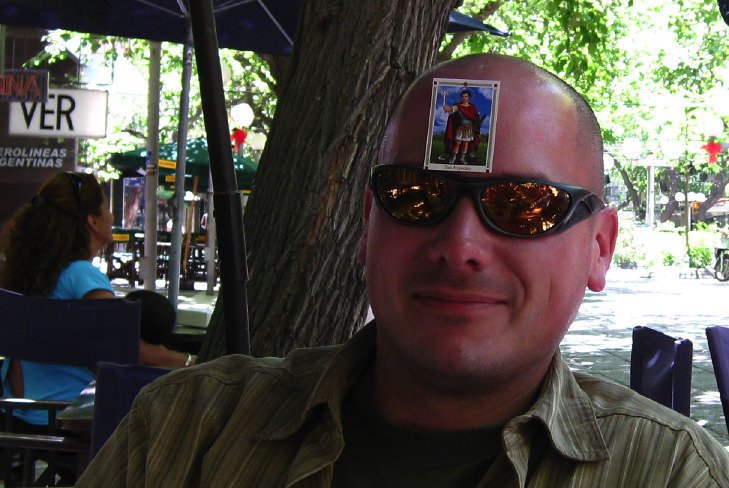

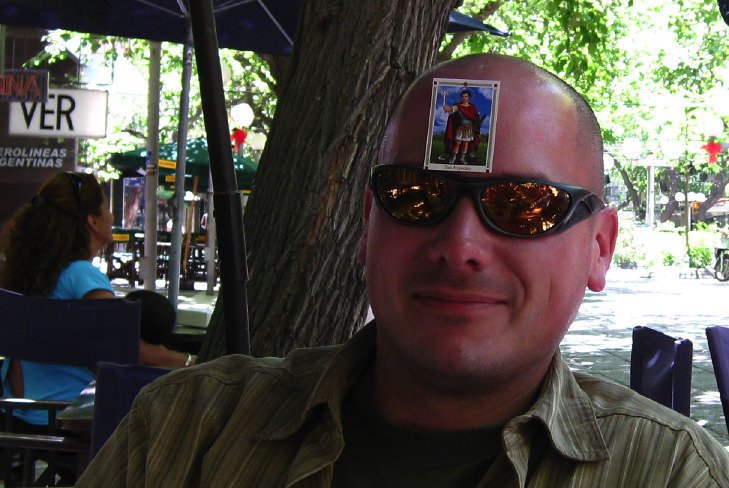

While we were talking a little rugrat came along and put a card with a picture of some sort of saint on it on our table, then left. We watched him put other cards on other tables, giving his gift to both tourists and locals alike. The card was some sort of prayer card invoking, if our Spanish was correct, which it probably wasn't, the blessings of the patron saint of expeditions. Wayne, who is definitely going to Hell, put the card on his forehead and thus earned the special attention of the saint. The little kid came back through and picked up the cards again from the people who didn't want them and collected a few centavos from those who did.

After a swing by the grocery store for a few supplies for the trip, such as bread, meat, cheese, beer, and wine, we returned to the hostel to catch the end of the siesta, which has to be the most underrated cultural practice in the Western world. The street out front of the hostel was quiet and empty as every one else was doing exactly what we were doing: Sleeping off a large afternoon meal in a shady place during the hottest part of the day. Also, banking sleep for the late night a head. Later in the evening we did have a few things to do, like transferring the white gas into our fuel bottles and getting gear packed up for tomorrow. It wasn't clear how we'd get to Puente del Inca, but there was a bus if nothing else.

Being culturally sensitive tourists, we realized that dinner doesn't start until 9 and only lackwits are seen eating while it is still light out. We found an absolutely top notch outdoor restaurant and enjoyed enormous, excellent steaks and plentiful wine for fifteen dollars each. The wine itself would have run $50 a bottle in an American restaurant and I had never even seen a steak like the one I couldn't finish. But almost as good as the food was the service: The waiters left us alone until we needed something, like another bottle of wine or the check. They didn't come around every few minutes while our mouths were stuffed with food to ask us if we were enjoying our food. And because they didn't bring the check until we asked for it, in Spanish of course, we didn't feel a rush to leave. It was nearing 1 am by the time we got back to the hostel for a few more beers.

The beers stretched into wine and we ended up on the roof of the hostel trying to find the Southern Cross, which I'd wanted to see ever since I figured out what stars were (i.e, not things painted on a ceiling). Down below on the street was an ice cream shop and it was hopping, even at 2 am. Little kids, teen agers, lovers, grand parents. Didn't these people have jobs that required a 5 am wake up? No, actually, as we found the next day, they didn't. But as the clock neared 3 am the cumulative effects of the long plane ride, the beer, and the wine overwhelmed even the strongest of us.

After taking a taxi to the other side of town where we thought the permit office was, we took another taxi back to near our hostel and began the permitting process for Aconcagua. This involved a trip to the permit office, staffed by two lovely women in uniform, then a trip to a bank to change our dollars (which we had been told was the only currency accepted for the permit) into pesos, then to a bill-pay place where we got a receipt, then back to the permit office where we finally got a piece of paper. We quickly packed up our gear at the hostel and hailed a taxi to haul us and all of our gear to the bus station. Time was short but Wayne managed to get tickets for us and our baggage (which was extra due to being truly excessive). While waiting to board we met a German named Peter who was also heading to Aconcagua. We quickly made friends but he disappeared on another bus. Not being able to communicate very well in Spanish this was a little worrisome, but the other people assured us we were on the right bus. Three Euros were on board as well, dressed in their mountaineering garb, which definitely made them stand out. The woman even had on lycra tights, which caused quite a large number of stares.

The bus rolled out of Mendoza and into the desert that surrounds the city and makes up a large portion of the Southern Cone. It wasn't long before we were in hot, dry country that looked for all the world like Nevada or Arizona. Bus rides are never comfortable, but they are more enjoyable in a place other than the US and I spent a lot of time gazing out the window and the ever more arid landscape. After a few hours we made a stop at a sort of nexus for buses and were able to stretch our legs and buy something to eat. And wait. And wait. And wait. We were waiting, it turned out, for the bus that Peter was on. It was having cooling problems and couldn't go more than 30 kilometers per hour. Of course, our good bus was unloaded and everyone packed onto the bad bus for the slow grind up into the mountains.

On our way once again, the trip seemed to drag on forever and I soon found myself dozing off. Now that the bus was heading uphill the driver kept it at 20 kph and we literally crawled our way to Puente del Inca, which is the end of the line for the bus and in between Argentine customs and the Chilean border.

We missed our stop, which was just outside of town, and the bus dropped us by the side of the highway with all of our gear about a quarter mile from Los Puquios, the outfit owned by a guy named Rudy Parra who had come highly recommended to us by a variety of sources we didn't actually know. Regardless, it looked like a well run company and they even sent a van out to fetch us from the road.

It was warm and sunny at 9000 feet and I could feel, though only slightly, the effects of the thinner air. I didn't have a headache, or a stomach one for that matter, and I wasn't short of breath or overly tired. I was just a tad bit slower than usual. The standard routine for people climbing Aconcagua via the Normal route is to hire mules to haul most of the needed gear to base camp, which is one day return journey for the mules, or any acclimated to the elevation, but a two or three day trip for those on foot.

Mules are amongst the strongest and most sure footed of pack animals, but they're also known to be stubborn and ornery when they don't want to do something. The muleteers were in the process of shoeing two of them and the battle than was being waged between the shoers and them mules was truly epic. I wasn't sure who won in the end, but the mules had new shoes after an hour.

We sorted our gear, dividing up what we needed for the hike in from what we needed only at and above basecamp. The high altitude gear was packed into duffle bags and weighed for balance, then tagged and set aside for the journey up. This took more than a hour, but we didn't have anything especially pressing to do for the rest of the day. After all, now that we were on our way toward the mountain beer was definitely verboten and without beer it is hard to pass time doing nothing.

While we waited I tired to make some art. The muleteers couldn't figure out what I was taking pictures of and now, looking back on it after two months have passed, I'm not exactly sure what I was shooting either. This is the best of the lot.

Kevin and I tried out our technical summit hats that are designed to gather and concentrate oxygen around the wearer's face. Wayne left his in Tacoma, supposedly on accident, though I have my doubts about this.

After getting our duffels ready, weighed, and tagged, we got a lift from Emmanuel to the hostel in town where we got a room with dinner for about $17 a person in our own room. Although slightly cramped, we would only be there for one night and there were not many other options short of camping.

The town of Puente del Inca, which means Bridge of the Incas, is net to a geologic formation much like you might see in Yellowstone, only this one is interesting and there are not hoards of retirees with cellphones and radios walking around looking lost. A standard market selling the usual tourist bric-a-brac was next to the hostel and in between us and the strange formations. No one tried the hard sell on us, which was very strange and almost Thai-esque: Laid back, confident, and comfortable.

We ran into Peter at the actual formation for which the town draws its name. There is a natural bridge spanning the river which is covered in calcium and other mineral deposits brought up from the bowels of the earth by volcanic activity. But I prefer the indigenous version of how the bridge formed.

Back in the day before whitey came to the Andes there was a great chief of the Incas whose son was paralyzed. Nothing could help the boy until a rumor came to the chief of powerful healing waters in the south where his son could be cured. The chief and his son set out with a retinue of warriors and made their way into the high mountains where they found the water that rushed up from the bottom of the earth. But between them and the spring was a raging river. The warriors wanted desperately to help their chief and thus embraced each other and formed a human bridge across the water. The chief and his son walked across the bodies and made it to the waters on the other side. After bathing in the spring, the son was cured. When the returned to the warriors they found that they had been turned into stone forever, thus forming the bridge.

We argued about whether or not Argentina and Chile had ever been in a shooting war together, a point that we finally resolved by going to the local military outpost and asking a guard on duty. The guard didn't speak much English and referred us to one of his colleagues, who showed us some impressive photos of various military expeditions to the top of Aconcagua and some warn out weapons. His English was only moderately better than our Spanish but it seemed that the egghead was right and there had never been a large scale conflict between the two countries.

The day was waning and we all had thoughts of tomorrow. It wouldn't be a long day, but we would be venturing up to 11,500 feet which was a significant jump for us. Moreover, none of us were touching beer, which meant that after a dinner of spaghetti with meat sauce we all promptly went to sleep, despite it still being light out. Tomorrow we'd start up the mountain and all of the joking, boasting, and bragging that had taken place over the last year now had to be backed up with action.