The Unstiffening

US-Canadian Border to East Glacier Park

June 15, 2009

No one was stirring when I blinked my eyes opened and tried to figure out where I was. The bed was warm but the air was cold and my feet were wedged into the frame of the too-short bunk. The hostel. East Glacier Park. The start. I slipped onto the cold floor and pulled my pants on. The cold air felt good against my bare skin and I declined to put a shirt on. I padded out into the kitchen area and started coffee going. Today was the day.

Duane, Rain Queen, Jym Beam, Chris, and I met over at the Two Medicine Grill for breakfast and to see if my future wife was still there. She doesn't know it yet, but I'm sure we're destined to be married at some point, though it isn't clear if she'll move to the Sound with me, or if I'll move into her teepee here in Montana. I've been seeing her in East Glacier ever since I first came here in 2005 and have been infatuated ever since. Pretty, funny, outdoorsy. And she makes a mean omelet.

After a stop at the post office, we had only one chore left to do. We made the drive to Browning, located the hospital, and inquired about the man. He was recovering in Great Falls and was going to live, though he had a broken eye socket, smashed teeth, broken vertebrae, lacerated liver, and other ailments. Browning is a sad town and I was happy to leave it for the slow ride to border. I dozed and tried not to think about the sound. The guards at the border were happy to let us wander over to the Canadian checkpoint for the obligatory photographs. Although Duane was the only one of us who had Mexico as an end goal, you can't start a hike from the border without at least one monument shot.

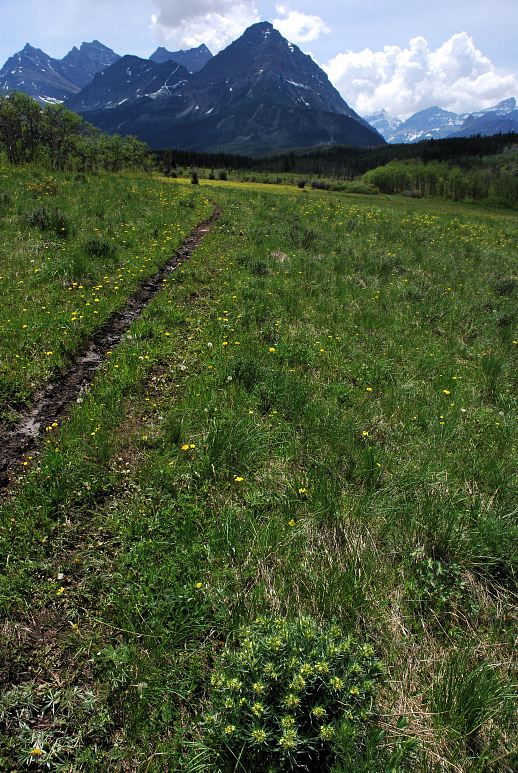

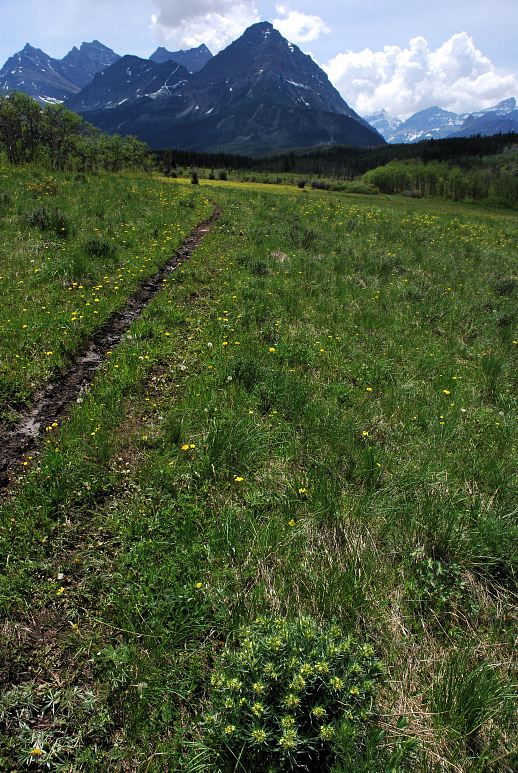

The last time I tried this I was broken inside. But out of the suffering of 2005 came a new light and a new way to live and I was now thankful for having to experience that pain. Now, four years later, I was strong both physically and mentally. We returned from the border and started down the trail toward the Belly River and Elizabeth Lake, our campground for the night. It didn't take long for me to separate from the others as I flew down the trail in a rush of excitement. For the next, well, however long it would be, I was going to be free and live with a purpose. I dropped out of the woods quickly and came into the broad valley of the Belly River just as a soft rain began to fall.

I didn't mind the rain and sang Muddy Water's classic, Mannish Boy as I strolled along safe underneath my umbrella. The route today and the next was in front of me: Cruise along the river into a mountain cirque, then climb up and over a pass the next day. The beauty of the park was in front of me as well. The beauty of another summer. Even though I missed my friends at home, I was happy to be here in the wilds of Montana starting another fool's journey.

The rain cleared and the sun came out on the valley, though on the far wall a storm still raged, with lightning and thunder and dark clouds. But it was there and here was sun and sweet smelling spring flowers. This is it, I thought. This is the place. But tomorrow would be another place and another time and life would be good then as well. I wasn't going to take a shower tomorrow and tonight I'd sleep on the ground, probably in a cloud of mosquitoes. And this was happiness.

I reached the Belly River ranger station and decided to hang out on the porch until the others caught up. There wasn't any reason to hurry off. The ranger was at home, though on his day off. We talked about the area and trail conditions and other little tidbits of life, like how one goes about getting a job where you get to live in a cabin in one of the most beautiful places on earth. The others showed and we sat around snacking and talking. We even made a move to leave once, but thunder and rain drove us back under the porch for a while longer.

With the passing of the rain we began the short trek to Elizabeth Lake, passing over a swaying suspension bridge that spanned the Belly River. These bridges get taken out in the fall in preparation for winter and spring floods, and are then put back in after the high water has passed. Without them travel in the park on foot would be quite difficult.

I wandered along, alone once again, toward the camp ground, stopping at a huge water fall, whose thunder could be heard from quite a ways off. The air was dense with droplets of air. Not falling water, mind you. But rather water that seemed to suspended in the air, much like a fog or mist. I didn't dawdle at the falls, however. Camp was close and I wanted to find a good spot.

As much as I like Glacier National Park, it suffers from a central defect: Quotas, permits, and designated camping. Quotas keep people out of the outdoors by restricting the number that can spend the night in a particular area. The permit enforces this. Camping is only allowed in designated sites, though in a few areas (hard to get to) you can camp freely and wildly, as befits as free and wild place. The designated camp sites in almost every instance (in any park I've ever been to with designated camping) are terrible. No one would ever willingly choose to camp there. This is done in the name of keeping things pristine and to prevent people from loving an area to death. To keep some measure of solitude. And so on. I don't buy any of that nonsense. Sure, areas around lakes will see a lot of traffic. If you want solitude, camp elsewhere. Would humans really cause that much damage? I doubt it, especially at any campsite more than 10 miles from a trailhead. Elizabeth Lake had great potential for a prime camping area. Instead the campsites were on compacted gravel with minimal views.

The lake itself was beautiful and after setting up my tarp and chatting with the two nursing students who inhabited one of the other campsites I wandered down to it and gawked. Our pass, aptly named Red Gap, was clearly visible on the ridgeline. Some gumbies were fishing in the lake, looked over by their guide, who didn't seem to know much more than they did. Who needs a guide to walk to Elizabeth Lake anyways? Maybe it was for his fine culinary skills. Later in the evening I watched him spend an hour making bean and cheese quesadillas. The gumbies, who seemed to work in the world of high finance, would later make strong passes at Rain Queen, though not while her husband, Jym Beam, was in sight.

The others rolled in and we sat around eating and talking and getting to know one another. And gossiping about the gumbies. Tomorrow would be the first pass of the trip and the first foray in to the alpine. It was like the night before Christmas when I was eight. The anticipation was excruciating. I don't know why I haven't gotten used to it, but the feeling is there every time I go to some place interesting. The feeling never lessens and what happens inside me never dulls. Maybe that's why I keep doing this thing.

Even with my earplugs in (first for the skeeters, then for snoring) I slept deep and well and awoke feeling strong and ready to go over the pass. Duane and I set out around 6:40 am and moved through the trees at a very slow, but sustainable pace. The cold, clear air was pungent with the fragrance of pine and fir and rotting leaves, a perfume better and stronger than anything that ever came out of France.

The wind was blowing, but the weather looked good and that encouraged us to linger on our way up toward the pass. As we gained elevation and began to leave the trees behind more views opened up of the valley above Elizabeth Lake. The spectacle of it was almost too much: Deep, U-shaped glacial valley filled with trees and a sequence of lakes, some large, some small.

The hiking wasn't especially difficult, which further slowed our pace: There was just too much to look at and enjoy. Too much to stop and gawk at, too much to wonder over.

We began to cross fingers of snow along the route, but the high winds of the area had scoured the pass of snow and we mostly had solid rock to cross.

I took photo after photo, stopping every few feet to fire away at something that caught my eye. Our campsite at Elizabeth Lake, for example with a neat, gnarled bush, stripped by the wind and the harsh environment.

Or the, probably, unclimbed mountains on the far side of the valley, complete with glaciers, snow tongues, and rocky cathedrals.

In one of the rare fits of motion, I got a sense of movement below me and scanned a grassy plateau a few hundred feet down. And then I saw it. The loping stride of a predator. It took a moment to recognize it: A wolf. In fact, a white wolf. The lope turned into a dash, though it seemed unlikely that the wolf could possibly know that we were up here. You can't see the wolf in the photo below, but it is near the lake shore at the far end. As if the park wanted to show off, two mountain goats lazed in the sun nearby, as if oblivious to my presence.

A few more switchbacks on the rocky trail and I was on top of Red Gap Pass, looking down toward another deep valley and, in the far distance, the plains of Montana. Duane was still fifteen minutes below me and Jym Beam and Rain Queen another half hour or so. The sky was clear, but the wind was blasting over the pass. Another pair of goats wandered around below me, equally oblivious. I found a few boulders that I could use to hide from the wind and settled in for a snack and a rest. It was only 9:45. The day was going to be good.

I sat on top and enjoyed the sun and the views as the others joined me behind the rocks. I was starting to get to know the others as we hiked together, and I was glad I had made my way into this group. Duane was on his first long trail, though had started the CDT last summer as well. After Pitamakan Pass, further south in the park, Duane had torn open an ulcer that he was unaware of after postholing repeatedly in the snow. He was extracted by the park service and went on to heal and then hike some portions of the CDT in Montana and southern Colorado.

After resting for a while we began the descent off the pass and found much more snow than on the ascent. Coming off a pass is always more difficult than ascending it, for when going up it is usually pretty obvious where to go if you lose the trail in snow. But descending you have no idea of where the trail might go if it gets buried. I followed my nose as best I could for a while, then we broke out Duane's GPS and determined that we were only a little ways from the trail, perhaps a hundred yards. We bushwhacked down the snowy slope for another five minutes and intersected the trail on the first patch of bare ground we found. It didn't take much longer to drop into the open valley below and start the traverse along it.

Rain Queen and Jym Beam are more known to the non hiker world as Melanie and Mac, two teachers from Maryland who were out on their summer break to hike part of the CDT, perhaps down to Yellowstone. Mac had hiked the Appalachian Trail before, with Mel joining him part of the way through. They were married not long after. They are one of the very few people to have completed a southbound PCT, whicih they did in 2004, the year after I had hiked. Additionally, they had ridden bicycles across the country, which was something I was interested in trying and I had ample opportunity to talk to them about cycle touring.

After eating lunch in a shady spot by the river, we finished the traverse of the valley and I started out on my own again as the others tended to blisters and lounged sedately. There was one more climb to go: Up and over the shoulder of a mountain and then down to the front country of Many Glacier. The park sits in a neat geographical area: The awesome mountains of Glacier National Park are the first mountains that a plains traveler would run up here and any view to the east seems infinitely long. That's good for the soul.

I climbed over the shoulder and rolled past a stunning alpine lake before dropping down off the shoulder and heading to the valley of Many Glacier. A rain squall opened on me, but only long enough for me to open my umbrella. I was feeling fine as I descended, stopping to talk to a park biologist who was monitoring a bird's nest of some sort. But when I reached the road my mood turned sour almost immediately. No one had done anything to me, looked at me funny, or in any way acted badly. It was just the presence of diesel truck after diesel truck along the road. The fat, complacent look on the faces of the drivers and passengers and the stink of their exhaust. Too lazy or too short of time or interest, they were caged behind their windshields trying to see something of nature without having to put in any effort. A traffic jam a half mile up the road really did it to me. Even the park tour bus decided just to stop right on the road. A cloud of diesel exhaust hung in the air from all the idling motors. And the cause? A young bear up on the hill side, viewable with the naked eye, but only just. I shook my head in content and kept walking.

My sour mood continued at the campground. I made my way over to the store and bought some aluminum foil to make a wind screen out of, along with some frozen yogurt and a can of beer. I knew I shouldn't feel angry or smugly superior toward the tourons and their lumbering vehicles, but it was really hard not to. Even though it had only been a day and a half, the time spent in the backcountry was already changing me. The presence of the road and all the vehicles upset that change and it wasn't firm enough in me to not be affected. I sat and drank my can of beer watching three Italian tourists practice their English on every passing person. Except me. I think I might have looked a little too scary. A park employee asked me where I was going tomorrow. "Piegan Pass," I mumbed. He said that it was still "winter conditions" up there and that he was going some place snow free. I half grunted and half growled and said no more.

I went to the campground and set up in one of the hiker sites and reflected upon the stupidity of the designated camping system. Rather than hiking a mile or two into the backcountry and setting up at some secluded spot where no one would ever be able to detect my presence, I was instead in the middle of a human zoo, surrounded by RVs, camper shells, and people with foldable picnic tables in tow. It was another few hours before the others showed up, and by then my mood had improved and I was no longer so salty. Tomorrow was going to be a trying day and I didn't want to do it hung over. I sacrificed an entire 1.5 liter jug of Carlo Rossi (red flavor) in favor of a can of beer and clear head. I suffer for my art.

The sky was clear and the sun shone with an especially pale light at 6 am when I emerged from my sleeping bag and started boiling water for tea. I could hear Duane rolling about inside of his tent, apparently also getting ready to start the day. It didn't take long for the two of us to get ready and we were heading out of the front country around 6:45, with Rain Queen and Jym Beam about fifteen minutes behind us. After a short walk down the road we turned off at Lake Josephine and left pavement behind us for the next few days. It was good to in the backcountry again.

The trail around Lake Josephine was quite nice and featured a shocking amount of bear scat.;this was definitely a favorite haunt of the local bruin population. After dodging around the lake and a boat launch area, Duane and I quickly hit snow, which was a bit surprising, but also not too unexpected: Piegan Pass had a reputation of being thick with the white stuff. Following a trail when it is buried under snow is something of an art form. There is no particular method that always works. Instead, you follow your nose and look for signs. Or, use a GPS. We used both: My nose and Duane's GPS. This turned out to be a good combination, for we followed the trail effectively over the snow and made our way to the base of the start of the climb up to the pass. Here we waited for the others. I spent some time looking at the map and the climb in front of us and convinced myself that it wasn't too bad: Standard snow climb up a moderate grade to a plateau that had been scoured by the wind of all its snow. The upper route, which was out of sight, was probably snow free and shouldn't prove too hard. In my boots, it would have been a piece of cake. But I was in trail runners.

After fifteen minutes, I headed back down the trail to see if I could find the other two. A quarter mile down the way I heard a faint human voice and broke into my best rendition of Mannish Boy again. I heard a cry of relief and Rain Queen and Jym Beam came into view. They had turned off on the wrong trail (to Grinnell Lake) and ended up having to ford a river or two and wallowed in deep snow to get to this point. We reunited with Duane and rested for a bit before starting up the climb.

Living in Washington I've grown used to going up and down snow slopes: You can't do anything in the backcountry for nine months out of the year unless you can deal with snow. But kicking steps in trail runners is never much fun. Your foot crumples, your toes go numb, and you never get good traction. Unless, of course, you have some sort of traction device. Which the other three had for their runners. Some times I'm not that clever.

We progressed up the slope, with the others following in my tracks, and occasionally I'd peak at Duane's GPS to make sure we were still reasonably close. The trail switchbacked quite a bit, but we simply took a direct line up the slope through the trees, effectively cutting all the switchbacks. Since there wasn't a trail to walk on, we might as well go direct. The valley below us quickly dropped away and we gained better and better views of the surrounding land. And the storm that was settling on top of us.

I began to pull away from the others, mostly out of desire to get off the snow and onto something more solid. I saw the top of the climb many times, but each time I'd get to the summit and realize there was yet more to come. Eventually the plateau came and with it large clumps of thick bushes that were hard to pick through. Eventually I managed to battle my way through and came to the end of the snow, almost directly on top of the trail. Looking back, my love affair with Glacier only grew.

The rest of the way was mostly snow free, with only a few fingers here and there to cross. While the snow was no longer much of an issue, the weather was rapidly becoming one. I topped out on Piegan Pass and found a comfortable rock wall to sit against and settled in for a lunch time rest, hoping that the others would get here before the rain did. Twenty minutes later I saw Jym's hat come up and over the rise of the pass, followed by his body and eventually Rain Queen's. Duane was not far behind.

Although the others didn't get much time to lounge at the pass, I had been on top for nearly an hour and was rather cold. We didn't dawdle much at the pass, for we had some work to do. The route down was actually a long traverse around the flanks of a mountain to an unnamed pass, with some steep snow along the way but also plenty of clear trail. At least it was clear until near the pass, and then it looked clogged with snow.

I led out across the snow and did my best to plant good, solid steps for the others to follow. Descending took a while. Rushing on snow was asking for trouble and even though there were only a few rocks and no cliffs below us, a slide was going to be measured in hundreds of feet.

The sky was getting blacker and blacker and a slight drizzle began to fall as we reached the unnamed pass. Looking back, Piegan Pass stood out like a meek little kid against a brutal sky and mountain range. Gone was the bit of clear ground and back came the snow. I picked a line through trees that I thought was more or less in the right direction and led out, my toes becoming numb with the cold.

High on a slope, leading to something other than Piegan Pass, I spotted a couple thrashing through the snow. Upon seeing us, they rapidly descended the slope, picked their way through the trees and intercepted us. Despite the awful weather and all the snow, they were day hiking to Piegan Pass and had gotten a little misplaced on their way up. This was a great score for us, as we now had tracks to lead us down out of the snow, which seemed to cover everything.

We stumbled through the snow, following the tracks as best we could, stopping only for a short break for some water at an unfrozen stream and to hide underneath some thick trees when rain began falling. Huddled, alone, in the small, confined cave of pine and duff, I felt strangely happy, despite being tired, cold, and wet. Jym was down the trail a bit and Rain Queen and Duane were on their way. I had friends around, the air smelled nice (a change from the Tacoma aroma I'm used to), and I could truly say that I had nothing better to do. I was where I wanted to be. When the rain let off, I loped down the hill, finally off of snow, and crossed one of the few roads in the park, along with the first CDT sign of the summer.

The trail descended steeply down from the road into a swamp of mosquitoes and gnats, which soured my mood somewhat. When the rain came back, the mood got a bit darker. When I saw the absolute dump of a campsite that we were required to stay in, I was downright salty. I quickly hung my food, set up my tarp, and crawled under it just as the worst of the rain hit. The sound of the rain drumming on the spinnaker fabric overhead somehow cheered me. It was a feeling of having triumphed over the rain: I had just barely beaten it. I lounged under the tarp for some time, waiting for the rain to go away. I knew that it would have to go away eventually. I knew that tomorrow could be glorious, or miserable. A bear could come into camp tonight. My tarp could collapse under the stress of a wind storm or the force of a broken branch. I could see a rainbow in the dark or witness a spectacular sunrise over the mountains tomorrow. None of that especially mattered. What mattered was that I was content under the tarp, listened to the pitter patter of the rain fall overhead, smelling the soft fertility of the forests.

A day without a pass, without snow, seemed like a great luxury this morning and the dark storm clouds overhead didn't make me cringe at all: Walking in the woods in a soft rain seemed almost appealing. We didn't have far to go today as we were moving around some too-hard-to-hike mountains to get in place to go over Triple Divide Pass tomorrow.

Not far from Reynolds Creek, our crappy camp in a mosquito bog last night, we felt, then heard, then saw Virginia falls, a huge, thundering cascade of water. While not terribly high, it was enormous and the power of the water was palpable.

The rain came back, falling lightly on us in the woods. I put up my umbrella and donned my jacket and gloves for a bit of warmth. I even put on my rain skirt to complete the transformation to armored hiker. Although I was walking slowly through the forest, I separated from the others once again and had the damp woods to myself. I was worried about Freefall and the other who were going over Piegan Pass today. It would not be easy in whiteout conditions, with the possibility of snowfall. At least they had our tracks to follow.

The storm wasn't much down here, however. The trees sheltered me from the wind and much of the rain and the only thing that got wet were my shoes and socks. The rain brought the smells out of the forest, driving the pungent pine aroma into my nose. The lowlands were so much different than the alpine zone we had been in yesterday that it hardly seemed possible. Tomorrow we'd be back in the alpine once again.

The rain let up after an hour and the clouds began to part. The trail ran above Lake Saint Mary, one of the central tourist destinations in the park. A major road went right to it, it was pretty, and had a lot of facilities for people who like, or need, to take a large portion of their household with them when they come to the natural world. I was glad I was where I was.

Around noon I stopped at a sunny spot with a view of the lake and a little shelter from the wind that found us now that we were out of the trees, the price to be paid for a little sun and a view. The others arrived a few minutes later and we enjoyed a long and leisurely lunch. Although it had cleared where we were, it was still looking rather awful back toward Piegan Pass where our friends were. I hoped they were alright. George, an experienced mountaineer, was with them and would be able to routefind for them just as I had yesterday. Still, I worried.

I left lunch a bit before the others and set out for upper Red Eagle Lake camp, where a piece of paper and a bureaucrat (i.e, a front country ranger) had told us to camp for the night. The trail climbed over a low shoulder through a burn area (perhaps five years old) and then began an Appalachian Trail like routing. The trail hiked toward a river, hit it, then doubled back on itself and went the direction I had just come from. After almost a mile I fished out my map to make sure I hadn't done something stupid. No, the trail was just stupid.

When I finally got to the bridge over the river I understood, sort of. Or, rather, I had a guess as to the silliness of the route. The bridge, maybe, had been originally where the trail hit the river the first time. Then maybe it got burned out or washed out by a flood and had to be relocated. This was a waste of brainpower, so instead I found a nice downed tree set well back from the river and took a crap, which was definitely more productive than thinking about why the trail was routed the way it was.

I waited until the others arrived and then set out once again on my own. Camp wasn't far, but the weather was beginning to set in and I feared the rain now. At the start of the day, far from camp, getting a little wet wasn't an issue, but now, so close to a warm, dry place, it seemed to be a major affront. I hiked quickly and eventually gained a ridge that looked down and over the lake. A fine lake it was, with craggy, snowy mountains behind it. Somewhere up there was Triple Divide.

I hiked down past lower Red Eagle Lake camp and finally came out of the burn area just before arriving at the upper camp. Unlike most designated sites in national parks, this one was more or less palatable, with a partial view of the lake and with a ground the harness of hot asphalt, instead of cold concrete. I got a choice spot and then settled in to relax. The weather than had chased me here seemed to give up the game now that I had shelter.

The short hiking days were hard to deal with out here. It enforced a certain idleness on us that was unnatural for a long distance hiker. We're used to being on the move from the early morning until the early evening. Even at a slow pace, you cover a lot of ground that way. Hiking ten flat miles just doesn't take that long. Although the park was very scenic, I was looking forward to leaving it and being able to set my own schedule for a while. I wanted to be able to walk for as long as I wanted to during the day and pick my own campsite. Glacier had the feel of wilderness-lite. Although it looked wild and scenic and you could get into a heap of trouble out here, it just wasn't the same due to the restrictions placed on people in the backcountry. Another few days and I'd be in one of the largest stretches of wilderness in the US. For now, though, I had a log to sit on that some kindly ranger had spent an afternoon chainsawing for me. Oh joy!

There was a beautiful pink glow inside my tarp to greet me this morning. The sun was rising over the lake, casting a gorgeous hue on my grey tarp. A fitting start to the day. We had Triple Divide Pass to deal with today. The pass marks the dividing point between Atlantic, Pacific, and Arctic drainages and was reportedly to be stunning. Rain Queen began the morning with some yoga down by the lake. A moose strolled on the far side, eating whatever it is that moose eat.

The four of us set out together as there was a ford of Red Eagle creek just above us and last year it was difficult, according to Duane. The ford this year was not quite so bad. Very cold and quick, but no worse than knee deep. I emerged on the other side and waved the others across, then began hunting for the trail.

We quickly separated once again and I headed out on my own, slowly crawling up the valley toward the pass. The trees became scrubbier and the air colder, with patches of snow here and there. And lots and lots of bear scat. I sang a mongrel tune for any bruins in the area.

The land became more and more scenic as I lifted out of the valley. The scent changed as well, with the damp, fertile smell of the woods replaced with the crisp, pungent air of the subalpine. Snow became more and more frequent and I had to start paying attention to where I was going, lest I lose the right way and end up being lost.

I climbed to a high plateau and looked at a steep, snowy face in front of me, shaking my head in anticipation as to what the others might think. Although a straightforward traverse, for anyone not used to playing on snow it would look rather intimidating. Rather than waiting, I kicked big bucket steps for the others to use and picked my way up the face and onto the next plateau above. The view down the valley toward Lake Saint Mary was stunning, as indeed every view in the park was.

I was now on continuous snow and picked my was as best as I could, following hints and signs of a trail when the snow broke open for a few feet. Leaving arrows in the snow or rocky cairns, I hoped the others would be able to follow my progress without difficulty. I should have been worried about actually finding the right way, but this seemed almost inconsequential: The pass was somewhere above me and with all the snow you might as well not stress too much about it. The weather, however, was a bit more worrisome. I moved efficiently up the plateau, climbed a steep snow face to a section of wind scoured trail. Solid, clear trail led to the top of the pass.

I settled in for a wait on top of the pass, hoping that the others would get up before the weather hit us. The descent didn't look super pleasant, but at least would be scenic. To one side of the pass stood Triple Divide Peak, which didn't look enticing at all as a climbing objective. Loose and crumbly and steep and exposed. Some people go in for that, but I'm far too cowardly for such things.

Forty five minutes later the others arrived at the pass, with increasingly threatening weather coming with them. A pass is to be relished, though, and we lounged as best we could give the blowing wind and the cold. The descent was going to take a while, and after food was had, we began the traversing descent.

Every day I try to be thankful for having the good fortune to be healthy enough to engage the natural world in a meaningful way. Today I wouldn't have to try. A grin was spread across my face, from ear to ear, on the descent. It wasn't hard to understand why. Medicine Grizzly Lake was far below us, perhaps two thousand feet, with huge cliff walls on one side, hidden plateaus with unknown lakes high above, a deep glacial valley dense with evergreens, and a high, traversing trail that seemed to stretch out to the ends of the earth. The weather be damned!

Every day try to be thankful for being healthy enough to do this sort of thing. I truly appreciate being physically, mentally, spiritually, and financially able to get to places like Triple Divide pass. Some of part of that ability has been deliberate choice. Some part of it has been luck or fortune or fate or whatever it is you want to call that part of human existence that is beyond our direct control. Even with the cold, blasting wind and the coming storm, I couldn't help but feel exhilarated.

The descent wound along the steep slope, running in and out of gullies, which were clogged with snow, requiring some very delicate work. I kicked big steps for the others, for a slip would result in a long, bad fall. At one point I crossed a gully with water running underneath, grabbed a large rock, and bashed a path through the rotten snow. It was slow work, but we eventually cleared the last of the snow gullies and descended into the trees just as the worst of the storm broke on us.

We collectively hustled down to Atlantic Creek campsite, another dump, and quickly set up our tarps. It was only a little after 2 pm, but we were done for the day. Even inside the protective enclave of the trees, the wind was howling, driving sleeting rain sideways, though my tarp kept me plenty dry. I spent a few hours under the tarp staying warm while reading and writing and wondering what we would do tomorrow with Pitamakan pass. Our speed wasn't very good and in a storm you have to move quickly and consistently through the alpine zone. No hour long breaks on top. It would sort itself out, no doubt. In time the rain would cease. I knew this. The storm would go away. I knew that, too. And I would still be here. And that was good.

The wind blew hard most of the night, though the rain let up near day break. At 5 am I crawled out of my sleeping bag to look at the skies and talk with the others. Things didn't look so nice, so we decided to come back in an hour and have another look. Another hour of sleep. Unlike mountaineering trips, when I never sleep much, I was out cold the moment I got inside my bag. I was just comfortable out here.

The weather looked slightly better, but blisters, weather concerns, and general fatigue pushed us toward a safe decision: Follow a trail out to the Cut Bank trailhead, then hope for a ride to Two Medicine. As is always the case, as we started heading out of the mountains, the weather began to look better and better, though that was mostly because we were leaving the mountains and heading into the rainshadow proper.

As we moved up the trail, Rain Queen, who was in front, suddenly froze and said, quietly, Bear. We all stopped and I slowly pulled my bear spray and moved up in front to take a look. The bear was off the trail now, in the trees, and we had a safe margin to pass. Slowly we moved up the trail, past the grizzly, and spent a few tense minutes putting distance between us and the five hundred pound bear. Only a quarter mile up we met a day hiking couple who were heading to Medicine Grizzly lake to fish for a while. We warned them about the bear and moved on, following the river to the trailhead.

The mountains were done for us, for today at least, and I was a little sad about that. But the fun thing about doing something unplanned for is that you get to make up your own adventure on the fly. It is like being a little kid again and playing in the neighborhood with your friends. You make up your own games, imagine your own monsters, and do whatever it is that seems right and good at the time. I had no idea what we'd do when we got to the trailhead, or where we would end up for the night. But I was happy to find out. The initial stiffness was starting to fade from me. I hadn't realized it at the time, but at the start of the trip I was still in weekend mode: Do this, do that, then some other thing, and go home to a shower, a beer or five, and a warm bed.

This was different. Long distance backpacking is fundamentally different than spending a weekend, or even a week, in the backcountry. We had a general direction to go, maps, and food. The rest was up to us. Sure, we could follow a line on a map, but that isn't very sporting. As we had progressed through the park, I had slowly started to gain the freedom of a full summer. I had some structure to it, but that wasn't very much. I was going to hike now. At some point I'd have to leave and go to Chicago. And then I'd do something else. The structure was there, but it was fairly minimal.

Last summer I had wandered from the Rockies to the Pacific, following a vaguely defined route called the The Pacific Northwest Trail. Sometimes I wasn't even following that. I rambled for about a thousand miles, without much of a plan, living as much as possible without any of the artificial structure of what some people call a normal life. And now I was doing much the same thing. Every day was important here. Every hour mattered to me. I'd never get this time back again and it was important to appreciate it as it happened, rather than just killing time.

We eventually reached the trailhead and took a lunch break. There wasn't much traffic on the access road, so we started walking down it. Only a half mile or so later a large pick up approached from behind, driven by the two day hikers we had met earlier. They, too, had run into the grizzly and decided to turn around and try a different lake. Rain Queen talked them into giving a lift to Two Medicine. Now, I think traveling on foot is the best was to see a place. But the second best has to be from the bed of a pick up. The wind zips by, the world flashes, and you don't have the protected feeling that you have inside the body of a vehicle. I was almost angry when I realized that I had dozed off in bed.

Two Medicine was front country, but we were able to swing free sites in a theoretically closed section. I hadn't developed much of a hiker hunger yet, but enjoyed a few gas station style sausages, frozen yogurt, and coffee at the camp store. Duane provoked peals of laughter from us when he started clipping his toe nails inside the store and then, looking up, wondered what we were all laughing at. It's easy to forget the sort of civilities that settled people expect after you spent even just a little time in the backcountry.

I'd like to blame it on Rain Queen, but I know that I'm really the one responsible for it. I put the idea into her head, just like a master yogi-er. I had yogi-ed a thruhiker, which is really quite a feat. Since it was so easy, I began to suspect that maybe she had yogi-ed me. It started easily enough. A casual browse through the store. A lingering look that bordered on an ogle. A soft touch with one finger and faint exhaling. A slight hmmmm. We found ourselves alone, in front of a display case of Carlo Rossi wine. The 1.5 liter jug variety, that comes complete with a finger ring up top for easy drinking. If I drank the whole thing, I'd hurt tomorrow. I needed a partner in crime. Carlo Rossi, in red flavor, came with us.

The campground was a typical front country set up, with plenty of space for RVs, trailers, televisions, generators, air conditioning units, six room tents with two porches, and all the other comforts of modern camping. Fortunately for us our campsite was behind a barrier to cars.

The screw top came off of Carlo as we began to set up camp. Can't camp in the front country without a little lubrication, I say. I like making up rules to things, but they have to be fun rules. Like not being on vacation unless you feel good about taking a slug of whiskey at 8 am. Or not getting distracted by the big picture. Small details that go every moment of your life are far more important than some over arching goal.

Rules, though, are like a line on a map. You should follow it for as long as you think it good, and you should go somewhere else, follow a different path, when you figure out a better way to do things. There are many people that wouldn't agree with me, but they have their own life to live and should live it in a way that is right for them. They should work long hours to provide a nice house in the suburbs for their family, take a vacation or two to Hawaii, have a lap top for each of the kids and a plasma TV in every room. They need rules and structure to make their lives worth living and not to break down into psychotic episodes every year or two. The structure makes life worth living because it gives them something they can grasp on to. Except, of course, when things change, like in the recession. Then you hear horror stories about families who "followed all the rules" and were now living on the street.

We sat around the picnic tables of the campground and watched cars drive through our formerly motorless sanctuary: The rest of the campground was full and they opened up our section. Such is life. With half a liter of Carlo in me, everything was fine. The wine made the rounds and eventually disappeared, which meant a trip back to the store for cans of beer, which we drank on the porch while looking out across the lake to the mountains. We also grabbed a package of enormous Beer Baron sausages to spice up our dinners. The first ingredient was pig heart. Yum. Even without the wine and beer and pig heart sausage, I suspected I would have been happy here in the front country. Rain Queen, Jym Beam, and Duane were good company. It wasn't raining. And I had plenty to eat. It was easy to be happy sitting on a picnic bench, talking with people you liked, and eating pig heart. There wasn't anything else I really needed.

The Carlo Rossi and Beer Baron had the expected effect upon all of us. It wasn't until the late, late hour of 6:45 that I finally set out, with the others a bit behind me. The sky was overcast and the air was cool, but there was no pass today, just a 2500 foot climb up to a place called Scenic Point, then down into East Glacier. After a bit of time in the trees, the trail climbed steadily up and into the mountains once again. Vegetation became scarce. It was the subalpine once again. A glorious place. The view back to Two Medicine was stunning.

As I quickly found, everything up here was stunning. There wasn't anywhere you could look and not see something of intense, immense, immaculate beauty.

People who grow up in war zones or witness brutality and violence on a daily basis are affected by this in a severely negative way. We know that. But the opposite is also true. The time spent around beauty and perfection affects you in a positive way.

We don't study this phenomenon precisely because it is positive: Study of it increases the well being of one's life, rather than simply preventing suffering. I have been to many beautiful places. I've spent a lot of time in the backcountry roaming about, both on this continent and on others.

But the Scenic Point area of Glacier National Park is one of the most sublime that I've ever had the good fortune to experience. On a sunny day, it still would have be exquisite. But today, now, with the clouds and Jacob's ladders of sunshine streaking through to the vast plains below, it was beyond belief.

i recorded one message on the digital voice recorder I was carrying, then another a few minutes later. And a third. Eventually I stopped that, frustrated with my lack of ability to describe not the land, for the photographs I was taking would do that better than I could with words, but rather to describe the strong emotions, thoughts, and feelings inside of me at this moment.

I couldn't do it. Maybe I could later. The plateau I was on seemed to go on forever, with every step revealing some new delight, some new pleasure that I could absorb and hold onto forever.

I sat on a rocky ledge and looked out over the plains and down to East Glacier. I looked out to Marias Pass and beyond, to the mountains of my future, as well as the mountains of my past. When I went into them last I was broken, but now I was strong. Now I was ready to be in them, rather than simply trying to survive them. This place, here and now, was special to me in a way that was hard to describe, as if coming from something beyond normal, ordinary sensory experience. I couldn't describe it because I didn't know what it was or where it was coming from or what it meant or why I was even here, in this place, at this time.

Eventually I had to leave. I hiked down from the mountains and through the dense woods of the Blackfoot Nation and right to the golf course of the resort in town. I managed to find my way to a sandwich and a beer or three before checking in at Brownies for the night. A few hikers were in town. More would be coming in. I bought supplies for the week's trek through the Bob Marshall and Scapegoat Wildernesses to Lincoln. Cold, wet rain came. A thick, strong storm. But I was inside and safe and warm and, for the moment, tame. It was a time to enjoy town for what it was: A place of plenty. Plenty of safety and warmth and food and friends.