July 6, 2009

An early night made for an early wakeup on my zero. I had a

big day ahead of me and needed to get started on it. I wandered into

the down town area of Anaconda, which seemed to have the same cancer

that I saw last summer infecting many of the towns along the Pacific

Northwest Trail. The cancer was in its early stages, but once

started it would not stop. The reasons for the town's existence were

slowly slipping away and it was clear that its best times were behind

it. Many homes were boarded up. Businesses were empty. The downtown

was not a place I'd like to be when the sun went down.

I wandered over to a dark, dank diner called Donovans, a

place without windows or light other than the pallid yellow glow of

cheap tungsten lights. The omelet was quite tasty, at least. As with

other towns dying of the cancer, the library of Anaconda was

exquisite, a beauty of a building that made one want to spend time in

it. I was unsure why towns with the cancer had such nice libraries,

but it seemed to be an established fact. I spent an hour and half

paying bills online and answering emails. The girl with pig tails had

responded. The girl from the Spring had written as well. My past

seemed to be repeating itself.

I swung by the post office to pick up my bounce bucket and

then headed back to the Tradewinds to sort gear, do laundry, and laze

about. Lazing is important. Storm clouds were building over the

mountains and a storm was expected later in the afternoon. With a man

made roof over my head, I could care less what the weather was

outside. I was safe and dry for now, and that was to be appreciated

no matter what happened outside. I called home and found that the

surgery was not yet scheduled. I was on trail to Leadore, 230 miles

away from here. A long push, but one that would avoid a long,

difficult hitch hike.

I called Springtime, and got only a voice message. Another

time. Ten day of food takes a while to find, re-package, and pack up.

And it weighs heavy. Fortunately Albertsons was directly across the

street and I was able to man handle the many shopping bags filled

with all the food I would have at my disposal for a long, long

resupply run. Although the pack would be heavy, I wanted to be able

to stay out for a long distance and preserve the feeling of wildness

with me. Although I very much liked coming into town and enjoying the

benefits of civilization, I also appreciate having the opportunity to

spend such a large amount of time on foot through a wild land.

The day wore on and I spent as much of it on my back

watching inane television and sipping bad beer. The light grew dim

outside and I was almost asleep when the Spring called. We didn't

have a lot to say, but she was concerned about me and wanted me to

call when I got out of the wildlands. We've just never been at the

right places in our lives at the same time. I fought to stay awake

for as long as possible, not wanting the softness of the motel to end

with sleep. Tomorrow I would be on a road almost all day with a heavy

pack and a long, long path stretching in front of me. Tomorrow I

would have to resume the hardness that existence in the backcountry

requires. But for now I had all the softness I could possibly want.

Another poor sleeping experience in the motel. As soft and comfortable as the bed was, the room was hot, stuffy, and without air. I had night sweats and the town food and beer brought constant heartburn to me, as they always do on zero days. I never get the burn at home anymore, but after a bit of time in the outofdoors a diet of processed foods just kills me. I wandered over to the closest gas station for coffee and pastries and watched Fox News for a while. I watched so that I would be even more hardened to the stupidity of media. I was going to be on the road almost all day long, but I had a radio to help with that. The heavy pack, with ten days of supplies, would not help that. I hit the post office on my way out of town and mailed my bucket to Leadore, noting Jym Beam and Rain Queen's bucket waiting for them in the stack of other hiker boxes. West Anaconda was definitely better than East, for there were fewer abandoned homes and the lawns were well cared for. I dodged over on a side road that turned into a pretty gravel country road, which kept me off the main highway for five miles or so.

I eventually rejoined the highway and turned on the radio

to drown out the sound of the cars going past. Road walking is a

matter of faith: You have to have faith that you're not going to die

at every moment from the carelessness of a driver, and you have to

have faith that it will end eventually. You look around you and try

to note things of interest. You imagine where different cars are

heading to and why they are going there in such a rush. You try to

imagine what sort of creature the drivers think you are. And you

remind yourself that the road will eventually end. I was quite happy

to turn off on Storm Lake Road, the most direct route into the

Anaconda-Pintler Wilderness. A home was at the turn off and, after

verifying that no one was at home, I took a lunch break at 1 pm under

the eaves of the house, for the heavens had just opened up and a

constant, though light, rain was falling.

The road quickly shrunk to an ill graded affair, yet there

were several cars on it, moving slowly uphill but, in a very

un-standard fashion, not offering me a lift up the hill. Storm Lake,

the end of the road, was evidently a popular destination. I wandered

slowly uphill, deploying my umbrella from time to time to keep the

rain off of me and grumbling about how heavy the pack was. The first

couple of days of a long resupply leg are always an adjustment. The

mountains came into view and the forest thinned appreciably as I

reached the lake, which sat at more than 8000 feet and was dotted

with snow banks.

Storm Lake was quite scenic, hemmed in by snowy, craggy

mountains and lined with trees. But it was also an unnatural looking

affair. It didn't take long to figure out why. It was damned. The dam

seemed to be more for flood control than for hydropower, which seemed

fitting considering the few people in the area. But if there were

only a few people here, why did the watershed need to be damned?

There were four groups of people camped along the lake and I hiked

across the dam, then rock hopped over an outflow, narrowly avoiding a

dunking, much to the disappointment of three youths fishing near the

outlet. I liked seeing young people in the outdoors, but this didn't

seem to be a rare thing in Montana. Here, in the western, wild part

of the state, the land was as much of a part of lives as the mall, or

Facebook, was for people in the Sound. I crossed multiple snow banks

and eventually found a patch of level ground with some shelter from

the elements by a few stout trees. A perfect campsite.

My tarp set up, I gathered water and began filtering it

through my gravity powered filter, for lake water is always suspect,

with very few exceptions. A fine pot of macaroni and cheese with

olive oil formed dinner and several fig newtons made a pleasant

dessert. The temperature dropped quickly and the wind picked up. I

would sleep well tonight, back in the open air of the outofdoors.

Although I sleep well at home, it is nothing compared to the comfort

of a cold night in some place in the woods or mountains or desert.

The air smells, no, tastes better. The bed is more comfortable,

though most people would look at the flimsy foam pad I was carrying

with some horror. And the morning is more delightful, free of alarm

clocks and with the gorgeous morning light shining in. Under a tarp

there is nothing to separate you from the environment. In a tent you

can pretend you are at home. In a tarp, you no longer can. And so I

bedded down and listened to the sound of the wind dancing in the

trees above me, happy and content and thankful for the time that I

had now and the path that was in front of me.

The windsong that had lulled me to sleep became a torrent, a

tornado, in the pitch black of middle night. Rain pounded the tarp

and the trees, but I stayed warm and dry and safe in the clutch of

trees under my tarp. I had chosen a good site. I listened to the

tempest outside and watched as the lake and mountain walls lit up

occasionally under the influence of a lightning strike. I went back

to sleep, unconcerned.

In the morning I spied thick clouds and

delayed my departure, hoping for good weather for my entrance to th

high country that was in my immediate future. I drank one pot of tea

and then a second. I thought about something that I had read last

night in Tolstoy. It was a passage that gelled much of what I had

been thinking about during my trip so far. The question was neither

original nor new. People had been thinking on it for millenia. Where

does the Human fit into the Natural World? Every other creature in

the natural world has a well defined purpose for its existence. It

knows the way. Only Humans are confused about how they fit in. Only

Humans wander about looking for a Home, looking for a place where

they belong. Tolstoy had no relation to the Natural World as I

understand the concept. He saw it through the lens of a upper class

househoulder, much as Hesse or even HD might. Yet, as they had, he

managed to see some large amount of truth in it and come to

conclusions that, though flawed in subtle ways, were mostly correct.

The power of mind, I suppose, though one allowed only to the greatest

of minds.

The passage was from the beginning of Tolstoy's last full

novel, Resurrection, written after he had renounced most of

his wealth and had tried to put into practice a form of Christianity

that Christ might actually recognize. He died alone on a bench in a

train station in rural Russia. Tolstoy and Dostoevsky are two of the

gifts of civilization, but ones that must be taken together to form a

complete whole. Each on their own some how fail to convey a message

that is complete and rich, but when read together they create a unity

that portrays well the existence that humans have to face every day.

The passage that had struck me was nominally a description of the

coming of spring in Russia, but held much more to it than a cursory

read would show.

The sun shown warm, the air was balmy, the grass, where

it did not get scraped away, revived and sprang up everywhere:

Between the paving-stones as well as on the narrow strips of lawn on

the boulevards. The birches, the poplars, and the wild cherry trees

were unfolding their gummy and fragrant leaves, the bursting buds

were swelling on the lime trees; crows, sparrows, and pigeons, filled

with the joy of spring, were getting their nests ready; the flies

were buzzing along the walls warmed by the sunshine. All were glad:

the plants, the birds, and insects, and the children. But men,

grown-up men and women, did not leave off cheating and tormenting

themselves and each other. It was was not this spring morning men

thought sacred and worthy of consideration, not the beauty of God's

world, given for a joy to all creatures - this beauty which inclines

the heart to peace, to harmony, and to love - but only their own

devices for enslaving one another.

I had hiked through the forest and climbed into the

Anaconda-Pintler Wilderness on my way to Storm Lake Pass. The trail

was carved directly onto the flanks of the mountains and was one of

the most beautiful stretches of trail since leaving the Scapegoat. It

traversed several snow banks, but the snow was soft enough not to be

too dangerous. I reveled as the storm departed and the sun came back.

The precipitous trail led to the aptly named Goat Flats, a large,

open expanse of grasslands high in the mountains.

I hiked along enjoying the sunshine and thinking about

Tolstoy and his view on the natural world. There was no evil, or

good, in it. It simply was. Predators ate prey when hungry and when

able. Species procreated either in established couples, or simply

came together at the right time, departing after their biological

responsibility was done. Some actions in the Natural World would

horrify our human morals. Adult, male bears will kill any young cubs

they can in order to induce the mother to breed again. Certain trees

will drop their seed equipped with a poison that will kill other

kinds of plants in an attempt to secure it's supremacy. But these

actions are neither good nor bad. They simply are what the Natural

World does. Nature doesn't care about the individual. Nature is in

the game for the species.

I traversed Goat Flats and made my way to the drop on the

other side. Snowy and slushy, the walking was difficult, but the

route finding wasn't especially difficult as parts of trail would

show up every dozen feet or so, keeping me on track. But the brief

sunshine wasn't going to last for very long. The storm was going to

come back. The switchbacking trail eventually bottomed out and I took

a break on a downed log near a stream, where I could drink water and

replenish my supply. A few granola bars brought new energy to me. The

woods were quite and hadn't been logged in quite a while, which was

something rare in Montana. Something that made me smile. I started up

toward Rainbow saddle, the next pass, as the weather began to worsen.

Man doesn't fit into the natural world the way a standard

predator does. We have remorse, at least some of us do, and we have

morals and qualms and we question our actions and debate which side

is right and which side is wrong and ponder the efficacy of one

solution over another and generally frustrate ourselves through

inaction and doubt. Those that claim they have found the one true way

are trying to sell you something and are to be avoided, much like

every sensible person avoids rolling a dung heap. Humans are

fundamentally unique in Nature and it seems to be the point of our

lives to figure out where we belong and what our role is. To make

matters worse, no two humans have the same role, unlike a wolf or cat

or elk. We each have to work it out for ourselves.

It had been raining, then hailing, then snowing on me as I

topped out on Rainbow Saddle. The views could have been spectacular

and the saddle a place to linger in the sun, but the temperature,

snow, and wind drove me from the heights immediately. My thoughts

turned from the abstract, very human ones that Tolstoy had brought

out to more animal ones. Survival. Aside from random dangers, the

chief cause of death and distress in the outdoors is hypothermia. For

now I was warm and relatively dry, but I was also sweaty from the

climb, which meant that my body would rapidly cool as my exertion

dropped. I hiked along quickly in an attempt to reach the safety of

the lowlands which, with their trees to knock down the wind, would

provide more safety than the scenic highlands.

I bottomed out, crossed the valley, and began the climb to

Cutaway Pass, thinking not about Man and Nature and how humans fit

into the world, but rather about the cold and the tiredness in my

body. Fortunately the skies cleared as I neared the pass and I was

able to take off my poor rain jacket and skirt for the last part of

the climb to the pass. On the other side of the valley was Rainbow

Saddle. And more storm clouds coming in.

I scurried off of the pass and dropped once more down into

the next valley, hustling as best I could in an attempt to reach

something like a campsite before getting dumped on once again. Though

I really needed to cover 25 miles a day, I was tiring of the cold and

wet and knew that I would be able to make up any short comings in the

days to come. The rain came back, but I was on the valley floor and

the trees kept much of it off of me, the umbrella taking care of the

rest. I had been hiking hard for three straight hours and the climb

to Warren Lake was a tiring affair.

I was quite happy when the trail leveled off and I began

to see the signs of a lake in the landforms around me. I made my way

through mushy, slimy trails and located Warren Lake and fine campsite

just off of it, sheltered by thick trees and well drained. Though it

was only three in the afternoon, and I would normally have hiked for

another four hours, I stopped at the campsite and quickly set up

camp. I had just retuned with a load of water and gotten under my

tarp when the heavens openned up once more and rain came pouring

down, followed by a ferocious hail storm. I shivered as water heated

for tea.

I gradually warmed up in my down jacket and warm hat and

gloves, with the hot green tea warming me from the inside. It was

actually rather scenic under the tarp, watching the hail hit the

ground and listening to them tick-tacking off my tarp. I was safe and

warm and my mind relaxed from the animal state it had been in since

leaving Goat Flat. Being bored wasn't a danger I faced. I had tea to

drink and the weather to watch and Tolstoy to read and a journal to

write in. Dinner to eat and to be thankful for. I watched the weather

slowly clear and improve and by my bedtime (i.e, 8 pm) there was

enough clear, blue sky to give me hope for good weather in the

morning. It was going to be cold tonight and I bundled up with my

water bottles near my sleeping bag to keep them from freezing solid

over night. I slept well, without doubt or confusion, and with the

reassurance that tomorrow I would awake in a place of beauty, with an

open future in front of me.

It was very, very cold overnight and the outflow leakages of the lake were all frozen into solid ice. The mucky ground from yesterday had been transformed into iron. It had dipped down into the 20s last night and even with the blue skies and the sunshine in the morning it was still bitterly cold. I made tea and drank it quickly for warmth, then packed up and hiked over a small rise to drop away from Warren Lake.

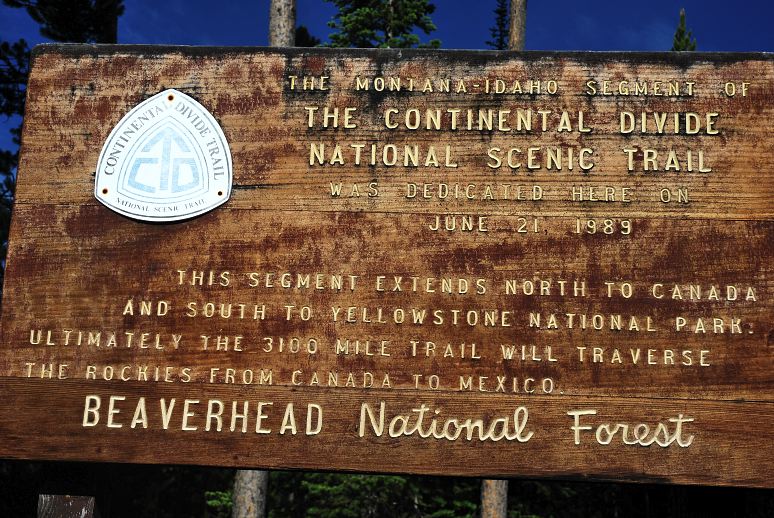

I dropped down into the forest and ran into a man with a

small pack and trail runners. Had to be a distance hiker. The man's

trailname was Scotland and he was finishing up the CDT with his third

and last section hike from Chief Joseph Pass to the Canadian border.

We exchanged stories and talked for a while about the trail and

various experiences before separating and heading our own ways. The

trail was pleasant and pretty enough to Rainbow Lake, with nice views

from the top to the Bitterroot Mountains, where I would be in a few

days after crossing Chief Joseph Pass.

The Bitterroot formed the border between Montana and Idaho

and I would have the fortune to traverse them for a few days to Lost

Trail Pass, from which I'd head to Leadore. If I could make better

mileage than I had been for the first few days of my hike out of

Anaconda. As I hiked, though, the pack would get lighter and miles

easier. The hike though the Anaconda - Pintler Wilderness had been

one of a sequence of ups and downs, with very few lengthy ridgeruns.

It made for tiring hiking without as much of a sense of having

finally earned ones pleasure. Stunning, for sure, but it required

work.

I found myself at Pintler Pass, looking out over the land

and facing a decision. In a short bit I would have the opportunity to

leave the CDT for an older version of it that required hard, off

trail travel, or to hike a new trail with more elevation gain, but

steady tread and fewer views. It sounds great when at home, in the

warmth of dry, cotton clothes to always take the harder path. But

when faced with the choice, everyone goes for the easy, sure route,

just like I decided to do. A lot of mud and muck on the descent, and

then some on the climb.

I had to make a critical left turn on a trail, away from

the old CDT coming in from the right, in 3.2 miles. I marked the

starting time and set off up hill, using the watch as a gauge for

when to turn. The trail climbed and climbed through scrubby woods

with few views. Shortly after an hour had passed I reached the trail

junction, complete with an old, battered CDT sign heading toward the

right. The left turn was marked with axe blazes and recent foot

prints. I turned left. After forty minutes of descent on a mosquito

choked, sloppy, not fun trail, I took a closer look at the map and

found that I was on the Beaver Creek trail, which diverged from the

CDT just a bit before I wanted to. And then it started to rain. I

wasn't happy.

I sat under a thick tree for some shelter from the rain.

Then it started to hail. I looked at the map and thought about

options. To save myself from a two mile, uphill walk, I could hike

several miles out to HWY43, then road walk that all the way to Lost

Trail Pass over several days, staying in front country campsites and

in cow pastures along the way. It would be a bit shorter than the

CDT. I went back uphill instead, getting lost along the way on a cow

trail. Fortunately the hail went away and once back on the CDT the

effort was rewarded with the best views of the day.

The trail ran along a talus field on the flank of a

mountain, with extensive views of the Big Hole below. The Big Hole is

the western most valley in the Missouri drainage, with the

Bitterroots as the western boundary of it. The Big Hole would be a

constant, left side companion for me for the next five days until I

made Leadore. It would, in fact, be with me until I started to detour

off the CDT and head to Jackson via the Teton High Route, if I made

it that far before going to Chicago.

I had intended on making it much further than I did, but

the lack of water along the high, open route forced me to stop early

at a set of mosquito breeding ponds called Park Lakes. Mushy and

mucky, there were no good campsites to be had and I finally forced

one inbetween a set of trees and settled in so that the mosquitoes

could feed on me better. I lathered up in DEET and wrote in my

journal, but mostly I felt sorry for myself. Stupid open tarp. Stupid

rocky ground. Stupid bugs. Stupid me for coming out here in the first

place. Better to stay at home and get fat. Remember what Bukowski

said: "Don't Try". I tried to use my sleeping bag to

keep the bugs off me, but it was too warm for that and I quickly

broke out in the sweat. So I stayed awake and just killed bugs. I

wasn't happy here and I didn't know what to do about it.

I awoke feeling better, especially since after 8 pm the temperature did drop and the bugs went away, hiding from the sub-freezing air as best as they could. Long distance hiking is primarily an exercise in holding your mind together. After the first week or two, most people find a rhythm to walking that their body's can maintain. Outside of a freakish injury (broken ankle) or an injury coming from over use (stress fracture) or a break down in body chemistry (malnutrition), the physical aspect of a long hike isn't the hard part. The mental one is. Outside of Scotland, I hadn't seen anyone since leaving Storm Lake. But simply seeing people isn't enough for a human. We need to have true engagement for a while. I hadn't had that since I left East Glacier, and that was starting to wear on me.

The trail was gorgeous in the morning. After hiking up and

out of the slop of Park Lakes, it ran along a ridge with extensive

views of the Bitterroots and the cloud choked Big Hole. I was at

peace once again, though I knew that was due more to the early

morning hour and less to any change I had made. I had experienced

this feeling before on various long, solo trips that I had taken on

trails or routes that didn't have much of a trail culture. There were

plenty of hikers out on the CDT this summer, but they were several

days behind me. I needed someone to hold onto for a while, to gather

mental and emotional strength from, like a hiking parasite. But I

also knew that they would be doing the same thing to me, and that it

was a mutually beneficial relationship.

Solitude is one of the signs of a true wilderness. But

solitude is easily transformed into isolation, and isolation is what

drives people insane after a long enough time has passed. When the

trail was stunning, as it frequently was, it was easy to enjoy

solitude. When the trail turned ugly, solitude was more difficult to

bear alone. Suffering by yourself is hard, but suffering with others,

knowing that others must endure the same ordeals that you must pass,

some how eases the burden.

The ridgeroute was stunning and the air was cold and

crisp, with long distance views to beautiful mountains. Hiking was

therefore easy. Even the burn areas that I had to traverse were

appealing, with bear grass and fireweed sprouting through the

blackened earth and charred trees. The route left the ridge and

resumed its bouncing nature. I stopped and rested, taking long drinks

of cold water directly out of a pristine brook that came down from

the mountains above me. Life was indeed easy.

I was nearing the end of the Anaconda-Pintler Wilderness,

and with it most likely the end of well maintained, easy to follow

trail. Miles would become harder to get and the chances of getting

lost, more properly misplaced, would become higher. I was going to

have to pay more attention to what I was doing and spend less time

thinking about abstruse topics. Surprise Lake literally surprised me.

Just beyond the lake was the sign marking the end of the

wilderness. I sat on a rock in the sun and lunched, with more pure

brook water. The maps held many warnings about keeping an eye on the

route, about a lack of trail, about paying attention. I slowly chewed

on some cashews and really did feel fine. The weather was beautiful

and the trail was good. I was in the middle of a sublime place that,

even without an official wilderness designation, was just as wild as

what I had just passed through. I set off and quickly found my

happiness increasing. The trail turned into a cairned route, which

was easy to follow along a high, slightly forested plateau.

It was clear that sometime in the last few years a trail

crew had come in and built up the cairns, cleared trail, and

generally made it possible to easily follow. Trail work is hard work,

but work that I suspected the people didn't mind doing. Good, solid,

rewarding work, unlike selling an insurance policy or a DVD player,

whose results would be seen and enjoyed by many.

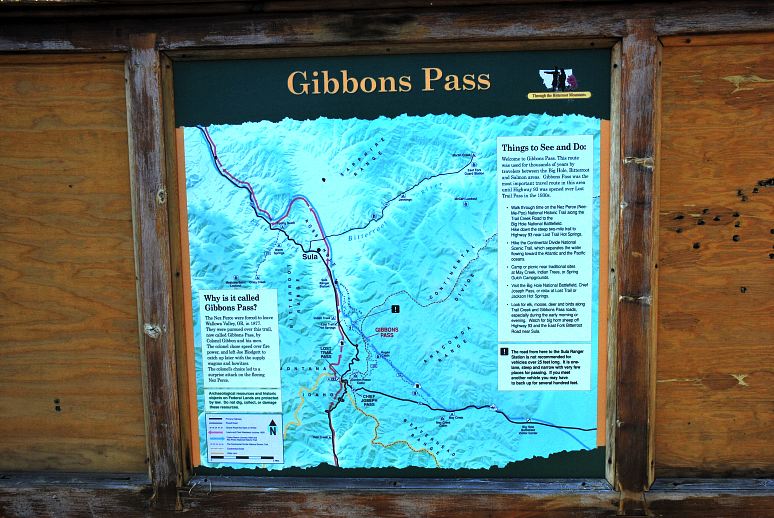

What would have been nice was a warning that there would

be no good water along the new route until reaching Gibbons Pass,

twenty five miles distant. The old route crossed water, but the new

one was up high on the plateau and just didn't. Although the

temperature wasn't especially high, the frequent burn areas meant

that I was soaking up a lot of sun and grew thirsty quickly.

The trail climbed high and began traversing more and more

snow. Invariably I managed to stay on route even across the snow,

which brought some measure of pride to me. Pride of craft, rather

than ego. I was pleased to be able to find my way out here. But after

five miles the trail dipped low and ran into a very dull lodgepole

forest. Rather than take a direct gravel road, the newly hacked out

trail bobbed through the woods, crossing and recrossing the road many

times.

I crossed one swampy area where it might have been

possible for a desperate person to find water, but my thirst was not

yet at that level. I rationed my water to last and knew that my body

could handle some dehydration and still recover tomorrow. Moving

slowly and trying to conserve sweat, I was pushing past the 30 mile

mark for the day as I approached Gibbons Pass. Gibbons Pass was at a

road. In one direction people could walk or hitch (unlikely on the

gravel road) out to a town. I walked in the other down to a pleasant

creek, where I found a nice car camping site and set up my tarp.

Almost 32 miles for the day, and my body felt it. I drank several

liters of water immediately and then set to making dinner for the

night.

It had been a physically hard day due to the lack of water

on the high route. My pack was getting lighter and I was starting to

be able to see my entrance into Leadore in four days. I still had a

long way to go to get there, but it was at least in site. Leadore

could be the end of my hike. Or I could move on to Lima from it. That

lack of clarity had not bothered me at the start of the hike, but now

that I was starting to get further and further from an easy

extraction point it was starting to wear on me. Unlike yesterday, my

body was tired but my mind was happy, and that was a good sign for

tomorrow. I needed to be strong mentally and spiritually in order to

continue doing what I was doing, and enjoying what had been a

spectacular summer so far.

Despite the road and the nearness of multilane highways, the hike in the morning had an empty feeling to it. It wasn't one of remoteness or of wilderness, but rather that it seemed like something was missing. The area was clearly a popular one for people in the winter, when the wide paths through the woods made for nordic skiing, snowshoeing, and snow machining. After a few miles on single track, I emerged onto a broad avenue and declined to depart from it when the CDT took a side turn. The two trails would both go to the same place, so there was no need to get back onto single track.

It was still early in the morning when I heard the drone

of vehicles and came to a massive parking lot at Chief Joseph Pass

and my first paved road since turning onto Storm Lake road several

days ago. At the pass are where MT43 and US93 intersect. Hitching a

long way on the first gets the hiker to Wisdom, Montana, while

hitching a very long way on the second gets one to Salmon, Idaho. I

was going to neither, as I still had four plus days of food on my

back, enough to make it to Leadore, ID.

I took a rest on the other side of the highway and watched

the cars and trucks rush by on their way to where ever. The day was

heating up quickly, which was unusual for it had been a decidedly

cool start of summer. The MT-ID border region, which I was just now

starting, had a reputation for being hot and dry and the trail poorly

signed and even more poorly kept. Lewis and Clark came this way on

their way to the Pacific and it nearly broke them. They went a much

easier way on their way back home.

I hiked into the woods and immediately noticed the lack of

axe blazes or other signage. I followed the route I was on and hoped

it was actually where I needed to be. Very quickly I met two

horsepackers, heading north. Sonia and Gunter, from Germany, started

the CDT last year at the Mexican border and were back this year to

finish up. I filled them in on snow conditions on the trail behind

me, provoking some mirth from them as I covered, at times, twice the

mileage on foot they did on horseback. I thought this funny as well.

We talked for bit, much less than I wanted, before we continued on

our own journeys.

I was very quickly depressed, almost as if someone had

come into my head and flicked the switched marked Bad Day.

After my encounter all I wanted to do was to talk to someone. To

anyone. I wanted people around me. I wanted to be somewhere else. It

wasn't a gradual change of mood. Rather, it was a load of bricks that

got dumped on me. The heat increased, as did the bugs. Rather than

just the usual skeeters, flies of all sizes joined in. At the top of

the climb I realized I had missed a critical water source and didn't

want to go back down hill for it. No matter, I thought, I still have

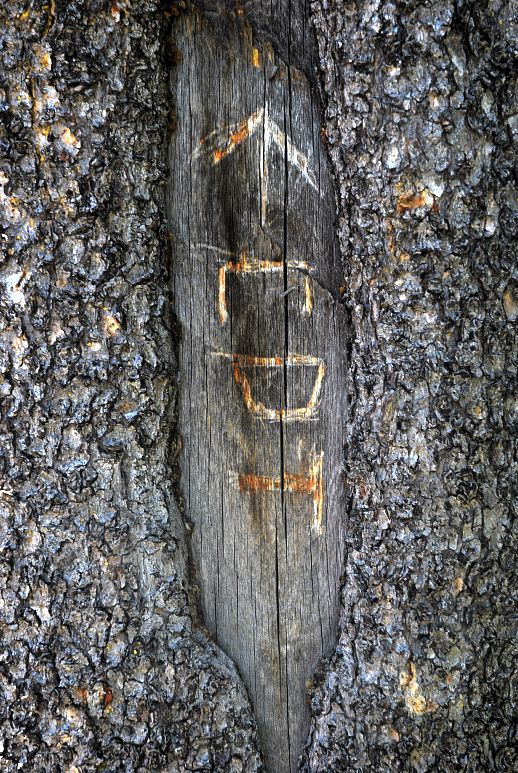

a liter left. The signage at a critical turn was nothing more than a

bit of knife work on a tree.

The character of the trail changed completely. The grade

of the route went through the roof, with the trail rarely having

anything resembling flatness. My pace slowed to a crawl as I labored

under the hot sun and swarm of bugs and began to think about water in

an intense way. The views were very nice and had the trail been

graded in accordance with what had come before, the route would have

been much fun. But as it was, I was staggering and looking for any

measure of relief.

The route led along a ridge broken by numerous passes, a

ridge narrow and thin and frequently burned on top. Lacking

sufficient water and tired and depressed, I couldn't enjoy what was

in front of me and seemed fixated on all that I didn't have at the

moment, which is completely the wrong way to live. I sat in the shade

of a few trees and drank the last of my water as I looked over my

maps, hoping for a water source somewhere near. There was a campsite

off the ridge, not far up, and that would have to have reliable

water. I hoped.

I hiked through a burned area to the top of a local knoll,

which held a sign on top indicating water in some vague direction. I

looked and sniffed, but wasn't about to wander downhill through the

burn to try to find it. Parched, I kept on, knowing that I could hike

for a very long distance without water until something really bad

happened. I just had to suffer for a while. Shortly past the sign,

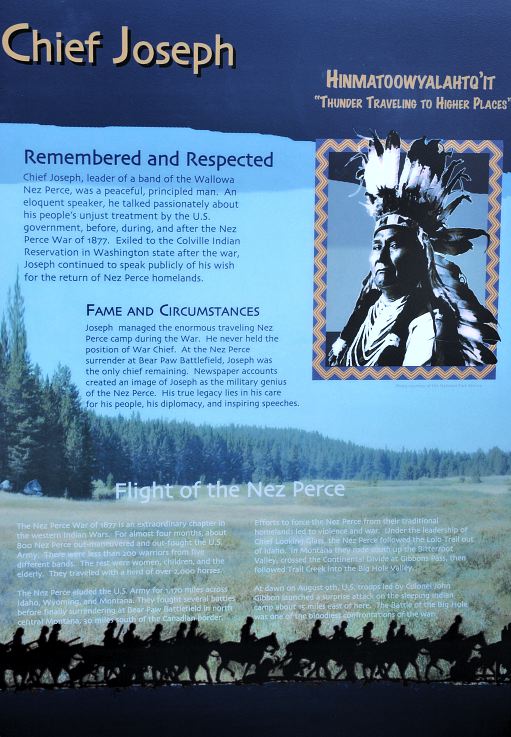

the route descended to a notch, where a side trail headed down to Nez

Perce camp. Of course, the trail was steep. It took a little while to

find the water source, which was, of course, steeply downhill. I

drank deeply from the ice cold spring.

After eating lunch and trying to rehydrate, I filled my

water bottles and set off back uphill to the trail and my suffering.

It wasn't much fun, even with water, and I was moving simply to move,

to get somewhere, rather than enjoying where I was, when I was. I

hated that. I was lonely and bored and needed to get my head in

order, or to do something else. I stumbled along the ridge, barely

paying attention to the long views and the remoteness of the land. I

should have been intoxicated. Instead I wanted to be domestic.

I rested at timed intervals, for when I sat I had no

desire to get back up again. I knew that I had to move out under my

own power, but I didn't want to. I wanted someone on a magic carpet

to fly in and pick me up and whisk me away to someplace where I could

indulge in all the senseless pleasures of the flesh, like Las Vegas

or Dubai. I was heading to Big Hole Pass, where a gravel road ran and

where I faced a choice. I could follow the official CDT or try a

short cut that seemed to get to the same place along a lower route

with water. The choice seemed easy enough.

I hit the pass and dropped down away from it, heading

toward Pioneer Creek, along which a road would lead me along and up

to a pass, the other side of which I would pick up the CDT again. But

the map wasn't entirely accurate. What looked like public land was,

in fact, a ranch, and I had to go around a fence to continue along

the road. And the road wasn't really a road: It was more like a track

that someone on an ATV drove a few times a year during hunting

season. The bugs grew worse. And I got more and more depressed. I sat

by the creek and looked at the map while drinking water. I felt like

crying. I didn't know what to do anymore. I didn't want to move

forward. I didn't want to go back. And so after fighting back tears,

I decided to head back to public land and camp for the night. When

tired and depressed, it is best not to make any decision. And so I

would spend the night and try to figure out what to do.

I set up camp and made tea, walking around to try to avoid

as many bugs as possible. The maps gave me options. I could go back

up to the CDT and follow it over the pass and eventually, in four

days, to Leadore. I could hike out along roads, parallel to the

Bitterroots and then back up to the CDT at a variety of points. But

what I needed now was some softness. I thought on it as the night

came on and decided to hike out to MT43 and walk that into Wisdom,

where I was sure I'd be able to find a place to sleep and to rest in.

And people to talk to. The air was still warm as I tried to sleep

amidst the swarm of bugs. It was not going to be a good night.

One of the worst nights in the outdoors. The bugs were relentless and it never got cold enough to put them to sleep. Ants crawled on me. The sleeping bag made me sweat. The buzzing in my ears kept me awake. It wasn't hard to get started at first light. I had about twenty miles to hike to get to Wisdom which, being on roads, would not take very long.

The gravel road led through stands of lodgepole with a few

long term campers parked in choice spots. A dog or two barked at me.

But the forest stretches didn't last for very long and I reached the

beginning of pasture and ranch lands with their resident hooved

locusts, er cows.

The scenery was really rather pretty. I was in the Big

Hole now, and the long, flat vista reminded one of the Midwest or

Great Plains. But behind me were the Bitterroots with their sharp,

snowy peaks and rugged foothills. Though it was nice where I was,

there was a storm brewing over the mountains and I was glad that I

was not in the heights at this particular time.

The mountains were where the CDT was and where part of me

thought I should be. I should be up there, suffering in the storm and

making progress down the trail. But that is thinking appropriate for

people sitting at home in front of computers. That is the thinking of

a mindless robot. I would get back to the CDT eventually, but first I

would make a stop at Wisdom and see what is there. I needed a break

from the isolation that I had been feeling on the trail and Wisdom

would give me that. It would give me an interlude of softness in a

trip otherwise filled with hardness.

To travel well is to be flexible with one's expectations

and desires. Rigidity of goals is a great way to accomplish a very

specific task, but it doesn't help much to do something worth doing.

There was gorgeous terrain that I would be missing by taking the

route that I was, but there would be great stuff ahead as well. And I

would get to see Wisdom as well. I have a thing for small towns with

interesting names like Wisdom. Or Liberal, Kansas.

As I approached MT43 the bugs increased to a crescendo and

I almost prayed for the storm to reach me, for its rain would drive

of the skeeters better than any DEET. They were everywhere. The cause

was easy to see: The fields were filled with standing water. It must

have been a very wet spring and early summer in the Big Hole. The

rain did reach me about two miles before Wisdom, giving me some

relief from the bugs but also forcing me to put up my umbrella and

get my feet wet in the ditch of the road, otherwise the spray from

the trucks and cars would have drenched me.

The mountains would have been a terrible place to be and I

was very happy to walk into the hamlet of Wisdom. The town had only a

few features. Motel on the edge of town. Two eateries. A store and

gas station and post office and church. Being Montana, it also had

several bars. Not much else. A few tourists lingered about and the

rest seemed to actually live here. I walked to the far side of town

and located a motel, but there didn't seem to be anyone there and I

retreated to a local eatery. A group of van supported cyclists were

finishing up lunch and trying to figure out which town would have the

nicest hotel to stay at. A pretty, young waitress in a very, very

short skirt brought me a grilled chicken breast sandwich with ham and

swiss. I liked Wisdom so far.

I asked the waitress about the closed motel and she went

off to ask a few questions. The owner and chef and mother of the

short, short skirt came over and told me that the owners were out of

town until the early evening. I told her my story and she immediately

had a solution: She rented out a cabin a few blocks away and would

knock $20 off the price for me. Done. She even gave me a lift over as

it was dumping rain outside. A nice, homey affair and a much better

deal than the motel at $45. It was nicer than my apartment back home.

The owner gave me a lift back to the main part of town

where I paid up and bought some supplies for the afternoon: Soda,

beer, and ice cream. Back at the cabin I showered and got cleaned up

and then sat, wrapped in a blanket on the sofa, and watched

Braveheart, beer in hand. I luxuriated in the softness of the

setting. Burrowing deeper in the blanket, I napped for a bit,

unworried about what tomorrow was going to bring. I called home and

got some news. The surgery was probably on for the 23rd, eleven days

from now. I wasn't sure what to make of it, so I drank another beer

and ate some ice cream.

The day moved into evening and I

walked into town for dinner at a local bar. There was no bartender,

so one of the locals opened beers for me, keeping a tic mark on a

beer coaster. The bar was pure Montana, with slot machines along the

wall, separated from the family portion by a non-continuous wall.

Smoking, of course, was perfectly expected. I drank a few bottles of

beer and ate a bacon cheeseburger while talking to whomever happened

to wander in. Unlike big cities, you tend not to pretend to not to

see people in small town America. The tic marks on the beer coaster

grew, and when I eventually went into the family part I brought the

coaster with me in lieu of a tab. It was cold, wet, rainy, and the

wind was blowing hard as I walked back to the cabin, very happy that

I was in Wisdom and not in the mountains. I was ignoring what I

needed to be thinking about, and that was the end of my walk down the

CDT. I was ignoring it until tomorrow when I would have plenty of

time to think over it. There was no reason to be depressed tonight

when I would have plenty of time for it tomorrow on the road.

Rain beat against the side of the cabin. I pulled the blanket tighter over my head and ignored it for a while longer. When the sound went away, I drug myself out of bed and made coffee, wandering around shirtless and shoeless on the hardwood and tile floor. It felt good to do that again. When I eventually left the sky was only mildly angry and I managed to get to the restaurant without getting too wet. I ordered two breakfasts and more coffee, delaying my thinking time to later, to when I was on the road and not in town. I had to ponder dates and times and ease of extraction and my bounce bucket and the Greyhound and regional airports and many other things that would not be very pleasant. The road was the right place for that. The girl in the short, short skirt wasn't there in the morning and I couldn't try to tempt her to come with me, not that it would have worked. So I paid, shouldered my pack, and hit the road.

Some times I feel like walking and today was one of them.

The sun came out and chased away the clouds, with just enough of a

breeze to keep the skeeters from settling on me, though I'm sure the

DEET helped as well. I started to do the math as two cycle tourists

passed me, waving and smiling and wondering why I wasn't hitching.

Ten minutes down the road I spotted them stopped in the distance. The

male was walking back and forth in the road while the female road in

circles around him. I wasn't sure what sort of dances cyclists do and

wasn't able to guess until I got up on them. The bugs were bothering

them so much, even through their tights, that in order to fix a flat

they both had to stay in constant motion. This seemed rather funny

for, though the bugs were horrendous, they weren't any worse than

yesterday.

I started to do the math as I left them. The surgery was

tentatively scheduled for the 23rd, giving me eleven days, including

today, to work with. I could be in Leadore in another four days. With

a rest in Leadore, I'd make Lima on the 21rst, which wasn't enough

time to get back to Chicago before the surgery. Leadore had no

facilities for getting out and I would need to hitch to Salmon, 50

miles away, to get to a Greyhound stop. Dillon was on MT43, my road,

maybe 65 miles from Wisdom. It didn't seem to make much sense to go

to Leadore. The only thing it had going for it was the fact that my

bounce bucket was waiting for me there.

It took me five hours, including breaks, to cover the

roughly 20 miles from Wisdom to Jackson, an even smaller town in the

Big Hole. I dropped my pack at the only store in town and went inside

for an iced tea and to ponder a bit more. I sat outside and watched a

few cars cruise into town. The two cyclists had made it here a bit

before me and were calling it quits for the day. I called my mother

and talked to her for a bit. Dillon it was. It would be the easiest

thing for me to do. I wasn't sure how I'd get to Dillon, or how I'd

get from Dillon to Chicago, but something would come up. A solution

would present itself.

That's how 99% of life seems to be. Concentrate on doing

the small, simple stuff well and the big, complicated things will

solve themselves. Or go away. Or kill you outright. I decided to stay

in Jackson for the night. It wasn't the most charming of towns, but

it had an authentic feel to it that I liked. And the views of the

Bitterroots were stunning. Besides, the amount of public land in the

Big Hole was small and I needed some place to sleep other than in a

cow pasture. Some more cyclists rolled into town and I chatted with

them. They had ridden the 45 miles from Dillon and were stopping for

the day. This seemed to be a common theme for cycle tourists.

The Jackson Lodge was the only place to stay in town. I

could camp for $15. Or stay in a room and bed for $30. Or in a fancy

room with its own loo for $50. I objected to paying to sleep on

grass, so I spent the $30 for a room and cozied up to the bar. This

was the end of my journey, I thought. I might as well celebrate.

Whiskey and 7-Up, an actual 7 and 7, was $3. I talked with the

bartender and owner in between chats with the various cyclists who

came in, loaded down with huge amounts of gear. Most of them had

their own laptops. Pedaling 45 miles must be hard when you have to

move 80 lbs of bike and gear down the road.

This was it. The end. But like Napolean's army in War

and Peace I had inertia and I wouldn't actually stop for a bit

further. I had to get to Dillon, after all, and then somehow to

Chicago. And I now had the problem of what to do with the rest of my

summer. I started thinking about buying a bicycle in Chicago and

riding home. The cyclists I were meeting were like old school

backpackers, hauling huge amounts of gear with them, most of which

they probably never used and never needed in the first place. Maybe a

thruhiker approach to cycling? I knew so little about it that it

might work out. I hadn't ridden a bicycle in nearly 20 years, which

made the prospects for success quite high: When you have no

expectations about the right way to do something, you can't fail.

That's the whole Beginners Mind thing. When you have it, everything

works.

I drank a second, then third, then fourth, then fifth

7 and 7 sitting at the bar. I bought and wrote out post cards to tell

people that the foot portion of my summer travel was ending a bit

sooner than I had wanted. I had wanted to hike down the spine of the

Tetons. To cross the Granite Highline in the Gros Ventre and enter

the Wind River Range, my first backpacking locale in the West. The

stunning high alpine lakes and granite walls called to me. Then the

Divide Basin, a flat, hot expanse of desert filled with things like

wild horses and pronghorn antelope. The Colorado Rockies. Parkview

Mountains. The Never Summer Range. Brewpubs in Boulder with Mags.

Sleeping on the summit of a 14er. Hanging out with Nitro on the

flanks of Mount Massive. Going 230 miles without resupply in the

pristine San Juan range and Weminuche Wilderness. Entering the Red

country of northern New Mexico. Ghost Ranch. The Gila. There was a

lot out there that I had wanted to see and do this summer.

I

wandered over to the store for a six pack so that I could drink alone

on the porch outside my room. It isn't true that the trail will

always be there. That's one of those lies that we tell each other and

ourselves to make us feel better. Sort of like saying that if a

relationship was meant to be, then it will happen on its own. Or that

true love will conquer all. I had the right mental state to do this

this summer. I didn't know when that mental state would come around

again. I had the time and was healthy enough. I took my shot at it

and it wasn't assured that I would get another one. Time doesn't come

again: Once you've lived it, its gone except in your memories. You

can't get it back. I took comfort in the fact that this really was my

decision and I was actively making it. I had thought about leaving

things up to my sister. About showing up later in the summer. About

hiring a nurse instead. But these things were repugnant to me. They

felt wrong. They were wrong. I was doing the right thing for the

right reasons, but that didn't mean that a part of me wasn't aching

inside. The last thing she would want to be is a burden. She wasn't.

Isn't. It was important to me, for me, to be there with her before,

during, and after.

I drank a can or two of beer on the porch

and then made dinner on my alcohol stove, in my battered cook pot,

perhaps for the last time this summer. The lifestyle I was leading

was a rewarding one that paid dividends to the spirit long after the

journey was over. Even with bad days, like the one after Chief Joseph

Pass, there was so much that was worthwhile that I was having

difficulty letting go completely. I could lead that life for a bit

longer, just a bit. I hoped that I would have more time, another

opportunity, to live so directly. But it wasn't assured and it might

not happen. Sitting on the porch, I realized that this could be it.

Maybe I would get hit by a car and spend the rest of my life in a

wheelchair. Or have an irate student suffering from PTSD shoot me. Or

get married, have kids, and settle in a terminal, middle class rot.

Another can of beer. I had things at home to look forward to. The

fall was going to be fun, I was sure. But that this might be my last

long trip was a possibility that I had to accept. And that was hard,

even if I was ending it to do something that I wanted to do even

more.

I wandered into the lodge and got a cup of coffee while pondering what to do. Might as well hang around and try to yogi a ride to Dillon. That brought me an hour of conversation with people heading to Tacoma, of all places, and their personal, pseudo-scientific theories on global warming. Much of it centered on a 24,000 year cycle of positioning relative to the sun. At least it was interesting. The cyclists were slow in moving in the morning, lingering over their gear and seemingly loathe to get on the road. They were planning on riding toward Wisdom. Might even stop there. Fueled on coffee, I gave away the last can of beer and walked outside, into the cold sun of the Big Hole. A sign said that Dillon was 48 miles from here. A fair piece.

I started walking for the rhythm of it. Step after step.

48 miles is a long way to go on the road. Probably have to camp

somewhere along the way, which was a problem that I could solve when

I had to. The two cyclists from yesterday caught me ten miles out of

Jackson, having gotten a late start. They were heading to Dillon for

the night and I might see them there. I doubted it. The ranch lands

of the Big Hole seemed to go on forever, but were at least scenic in

that sort of pastoral way that makes people like Europe so much. Only

Montana pastoral was smelly, dirty, and very real. It wasn't Heidi

at all.

I topped one minor pass and several cyclists heading

toward Jackson passed me. And then some more. A British man stopped

and chatted for a while on his way to the top, finding what I was

doing to be quite natural. To him I wasn't a homeless person. I

wasn't a hobo. That was a rare talent of vision, and not one that I

would have thought Europeans capable of. But he had it. We talked for

fifteen minutes about cycling before heading on. I didn't make it

another half mile before another cyclist stopped me.

This one was different though. He actually knew me, or

rather knew of me, when I explained that I was bailing off the CDT.

He had hiked the PCT a few years ago and knew me from comments from

me in one of his guidebooks as well as some of my online journeys. I

asked some cycling questions as I had a thruhiker in front of me.

Should be doable. Might be able to make it to Tacoma from Chicago in

a month. Might be tight, sort of like pushing up a 30 mile per day

average on a long hike. Maybe.

I had hiked for about 20 miles

when a state highway worker, who had passed me several times in his

distinctive red truck early in the day, pulled along side and asked

me if I wanted a ride into town. Why not. I'd probably walked far

enough for now, and hoofing it another 28 miles wasn't especially

appealing. If my trip was over, let it be over. 550 miles in a month

was enough. The man lived in Dillon and was on his way home from

work. Two cyclists were broken down by the side of the road and we

stopped to give them a lift back to Dillon as well, for they had just

left it that morning before breaking a chain due to a poorly secured

loaf of bread. I was liking the idea more. The highway worker dropped

me off at the local Motel 6, but hauled the two cyclists to the Super

8 which, though on the main drag, was further from the center of town

and the bike shop that they needed to visit.

The Motel 6 was

clearly not like others that I had visited. Plush inside, appealing

grounds, art of the walls. I got a $20 discount for looking pathetic

and explaining my situation. And they had a computer hooked to the

internet in the lobby, something I would need to arrange for my

extraction to Chicago. I made a trip to the store for some beer and

snacks before I took my shower. I like to have a beer in the shower

when I get to town. I added a liter of Old Crow for celebrating

purposes. The trip really was over. From here I'd be motorized the

rest of the way to Chicago. Somehow. I stood on the porch in the

warm, dry sunshine of the afternoon and drank a can of strong beer.

The afternoon wore on. I started looking for cheap tickets

at various towns. Oddly enough, Bozeman, a small college town north

of Yellowstone, had the cheapest flights to Chicago, beaten only by

Salt Lake City, which was too far to go to. Mind working. Who did I

know in Bozeman? Ryan Jordan, of Backpacking Light fame, lived there

and had given me a lift up Hyalite Canyon in 2005 during my other

aborted CDT hike. Then it clicked. Sam

"Mule" Haraldson lived there now. I knew Sam only from

the internet and from our common hike of the Pacific Northwest Trail.

I was sure that he'd be up for a visit for a few days before my

flight. I bought the ticket for the 20th and sent Sam an email. There

was another email to send. This one to the girl in pigtails. For the

future.

As it tends to do, afternoon passed into evening and I

began to feel the ache of town and the pull back to the mountains.

The food I ate was too much and too heavy and the beer and whiskey

conspired together to give me heart burn. The television was inane.

The air inside the confines of the room stuffy and overly warm. It

was constricting. I went back out to the porch and stood in the cold

air outside, glass of whiskey in hand, and looked at the lights of

Dillon. How many times had I ended a long trip? I should have been

used to it by now. But I wasn't. It was always bittersweet when you

reach the end of the path, the road, the journey, whatever it is that

you want to call it. Your labors have ended. But the joy is also

gone. The thrill of every day, of not knowing what the new sun will

bring to you, is something lost in the regular habits of daily life,

when we do things that need to be done and neglect those things that

bring us true happiness. The air was cold on my shirtless chest. The

concrete cold on my bare feet. Maybe Bukowski was right after all.