Quinault to Quinault Loop, Olympic National Park

July 22-25, 2005

I spent a month hiking on the Continental Divide and in the Rockies in general, but never really got into a groove, never really enjoyed myself. My head and heart were back at home and I needed to return to clean up a mess in my life that began spilling the night before I left for the start of the CDT. Mess cleaned up, everything healed, I set out for the Olympics and a nice loop that I had had my eye on for quite some time. I drove out to Lake Quinault, in the far southwest of the park, and picked up a permit from a jealous ranger. He, too, had apparently had his eye on it for a long time but hadn't been able to score enough time off to do it. After dropping my car at the North Fork Quinault Trailhead, where I would finish in a few days, I shouldered my pack and set out to walk around to the East Fork Quinault Trailhead. Four miles and two hitches got me into the Graves Creek campground, where I spent the night.

I was incredulous when I heard the pitter-patter of rain on my tarp around 5 am. It had been sunny and clear for more than a week in Puget Sound, something that must approach a record. I had grand plans to thump up the Enchanted Valley to Camp Siberia, drop my gear, and then climb up Mount LaCrosse. That meant getting started now, in the rain. Remembering a maxim from the AT, "Only a great fool leaves a dry place," I pulled the sleeping bag over my head and dozed until around 8, when the rain had ceased.

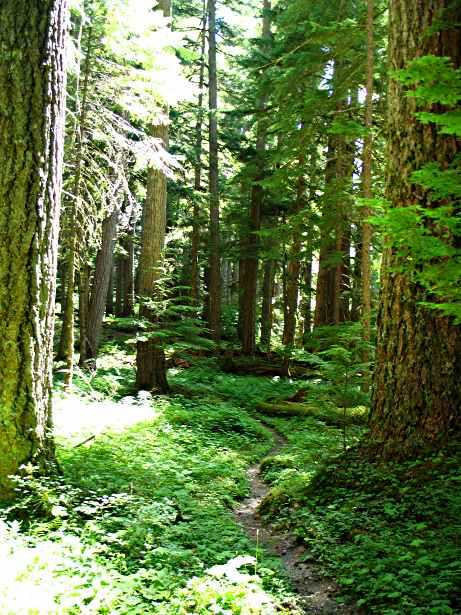

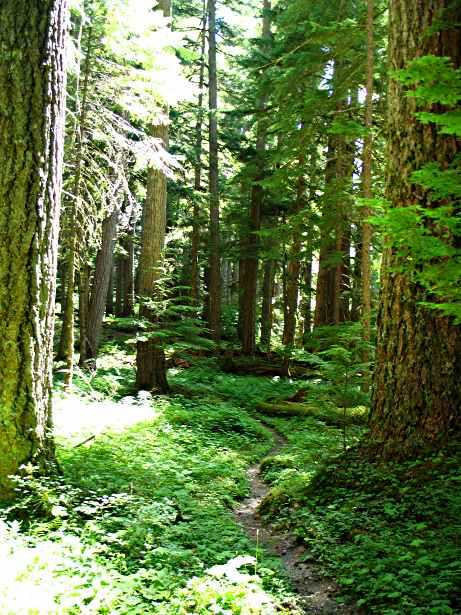

Nothing but grey skies and low slung clouds when I finally did poke my head out of the tarp. No matter, I thought. This will burn up in a few hours, and I'm in a valley anyways until the late afternoon. I packed up and was rolling a little after 9 in the morning, a shocking lazy start. This too, didn't matter. Everything seemed to be just right. The contrast with my month on the CDT was shocking. Everything there was a struggle. It was either too hot, or too cold. There was too much water or not enough. The mountains were too high or the trail was too flat. My mind and my heart just were not into it, and this made my body tired and sad. Today, everything was aligned. The rainforest was exactly where I wanted to be. I was doing exactly what I wanted to be doing. There was nothing else out there. I didn't even harbour any animosity to the Devils Club that lined the trail and occasionally reached out to sting me. I was back.

I cruised up the trail, passing a few day hikers on their way down already, along with some older backpackers with enormous things strapped to their backs. I thought old people were supposed to have garnered some wisdom during their extended time on earth, but it seems this might be an erroneous assumption given the sweat on their brows despite the fact that they were heading downhill.

As the trail began to tilt, every so slightly, and climb toward the Enchanted Valley, I started to actually become excited. After all, you don't hang the tag of "Enchanted" on something if it is a real dump. Then again, witness Greenland. My excitement spread to my present location and I started to see the little features of the rainforest, not just the huge, moss draped trees. Things like a slug the size of my finger, working over a leaf. Doing something to it. Everything out here is alive. Life permeates the entire land, not just bits and pieces of it. The incredible density of life in the Olympics makes it a special place, just as the lack of life makes Death Valley special.

As I rolled into the Enchanted Valley via a convenient foot bridge, I remembered that the weather was not really all that great. It wasn't important in the rainforest, but now I was heading toward the alpine. I had a brief glimpse at a glacier as I traded forest for field, but the clouds quickly closed in. I had some time as there was no way I'd be able to get up LaCrosse today. A ranger station stood in the field and made for an excellent lunch stop. As I ate, a hiker came strolling up the trail from my direction. I had passed him about twenty minutes before reaching Enchanted Valley and was wondering what his story was. Carrying a microscopic pack, yet with a guitar and other things hanging off. Had the beard, but was in boots. Emery, for that was his name, was from Baltimore and was out for two weeks. Glancing at the size of his pack, I thought he was just in the area for two weeks. No, he was in the park for two weeks. A little shocked, I asked him what he was doing for food. Five pounds rice. Jerky. Peanut butter. Cheeze Whiz. I watched in amusement as he pulled out his rice sack and proceeded to eat the kernels, raw. "I just make sure I drink a lot of water."

Emery had graduate from the University of Baltimore in the spring time and was now out west, hitchhiking around, with plans to visit Glacier, Yellowstone, Grand Teton, and eventually the Southwest. Hiking here, staying there. Making friends and enjoying a life without structure. And he was happy doing it. A few hundred dollars in a bank account and no time limit. He thought he might be able to stay out until December on what he had; maybe longer if he got some day labor jobs. He was doing his own thing, even if most people wouldn't understand it, in his own time. He'd been mistaken for, and treated like, a bum. He'd slept on park benches because he couldn't afford a $25 a night hostel bed. He was eating raw rice. We swapped a few stories from the road and then I pushed on, wanting to make it up and over the pass before the weather got worse. I'd see him at Camp Siberia anyways.

The fields of Enchanted Valley were quite extensive and I was sure that there was much that was being hidden from me by the low clouds. By the low, beautiful clouds. Like a pre-teen boy enamoured with his first love, the land here could do no wrong. While I could only see the bottom ends of many waterfalls, the low slung clouds gave the place a prehistoric look and feel. As I gained elevation, and the sweat started to roll off of me despite the chill in the air, I took pleasure in the strength of my body. Almost every day, every mile on the CDT was physically tiring. Not because the terrain was tough. Indeed, much of it was easy. No, it was hard because my mind was sitting a thousand miles away. My mind was here with me now, and the walking was easy.

I passed a sign advertising the world largest known western hemlock. I didn't even hesitate, despite the fact that the trail led downhill and I was going uphill. Like a tourist drawn to a large ball of twine along some interstate, I just had to see the tree. A pack sat against it, but the owner was nowhere to be seen. The tree was large, about 9 feet in diameter, but almost all trees out here are large. My curiosity satisfied, I returned to the uphill grind, climbing higher and higher into the clouds.

At a trail junction, I ran into three backpackers taking a map and food break. They had come up from Staircase, my usual trailhead, and walked up the North Fork of the Skokomish before swinging around to Marmot Lake and O'Neil pass. They were on another loop that I had had my eye on. Happy, despite the weather, they were going to be camping near me and then heading out the next day. I wished them luck and set out to finish off the pass.

Anderson Pass was a little notch in a clump of forest between two mountains, holding a microscopic pond, but not much else. Pleased, but a little chilled, I decided that a rest break would not be the best of plans, especially since Camp Siberia was only a half mile a way. I pulled a final Snickers bar for the day and munched on it as I strolled downhill, through the clouds. As I came out of the forest to traverse an open, meadowy slope, I spotted a large figure sitting in the flowers thirty feet in front of me. A nice 200 pound black bear was doing nothing in particular that I could see. Just hanging out in the flowers. Unlike almost every other black bear encounter that I've had, this one did not take off running in the opposite direction. It just sat in the flowers and looked at me. I backed away slowly and around the bend, eventually reaching a spot where I could still see the bear in the meadow, and sat down to wait it out.

The bear eventually got up and walked a few feet to some more flowers, then sat down again. This might take a while, I thought, as the bear really seems to like the flowers there. Time passed and new clouds rolled in, obscuring my view to the point where I could only make out vague outlines of something dark and large in the meadow, sometimes moving. After 20 minutes I could no longer see the bear. Shouldering my pack and hoping for the best, I walked slowly through the meadows, calling softly to the bear and warning it as to what I would do to it if I saw it again. I never did. Camp Siberia, a run down, though spacious shelter, was located not far away, perhaps 300 crow yards from the bear meadow. I was happy to get out of the wind and put some warm clothes on. The location reported got its name from the cold winds that sweep off the Anderson Glacier directly above the shelter. I hadn't seen a glacier, but I could feel the cold winds and this place was the bloody Ritz in comparison to my tarp. After getting my warm stuff on, I noticed, among all the carved graffiti here, a single, solitary letter that someone had thought to put on one of the support posts. I thought about it for a minute, then decided that this really was where I wanted to be. When there is no one else around, there is no reason to lie to yourself. I fetched water and made tea, whereas a month ago I would have moped.

I sat out, partially in the wind, and drank down the hot tea, watching the clouds blow by and wondering what the land around me looked like. This was a spooky place in the mist, but also one of beauty. I didn't think that many others would find it beautiful, but in my mind it was, even if there was no good reason for it.

After eating dinner, I broke out the rum and sat in the shelter reading The Symposium for a while, they switched to Edward Abbey (Abbey's Road) when the rum clouded my head too much for understanding even a simple Socratic dialogue like The Symposium. A marvelous discussion on the nature of Love, The Symposium is also an actual dramatic, literary piece, unlike so many other of Plato's dialogues. Around 8:30, more than 3 hours after I got in, Emery strolled in looking cold, but very happy. He had been in search of the Anderson Glacier, but couldn't find it. We swapped more stories about the road, chatting to hiker midnight, which here is 9:30. Two backpackers rolled in, putting off bedtime further. They were out to climb Mount Anderson and thought it was a non-technical stroll. I suspect otherwise. They had an ulterior motive, however. They were out to collect samples of a certain worm that, reportedly, lives in the glacier. They were cooking dinner when the rum overcame me and I fell into a deep, peaceful sleep.

The others were up early and gone before I opened my eyes long enough to see sunshine outside the shelter. I was happy to get up and start the day. I couldn't remember the last time that I had woken in the outdoors and was happy to do anything. Probably the Grand Canyon trip over spring break. I was actually interested and excited about what the day might bring. The good weather had something to do with this, as did the fact that I had an easy 18 miles to hike today. But, while drinking tea and talking with Emery, I knew that I was healthy again. That I was strong again. That I was back in that place where everything is united and there is no struggle. Just live. Nothing else. I packed and said my goodbyes to Emery, as our paths were to diverge here. I hoped I might see him again, hope that was not without justification, as the community of wanderers is smaller than one might think.

The path led downhill through dewy, flower filled meadows that soaked my legs and shoes. The openness did reveal some mountains in the area, though these were mostly minor. The scent of the flowers hung in the air, combining with that fecund smell that Russians seem to describe so well. Everything alive, nothing dead. Even the downed trees were covered with moss and mushrooms and other living beings.

As I strolled down the West Fork Dosewallips trail, I mused on the difference between pity and compassion. Knowing the difficulties in defining such abstract concepts, I limited myself to giving a superficial description only of the difference, not the nature of the two ideas. Pity has always seemed to me to carry a negative connotation. When one feels pity toward someone, one is glad that the bad things happening to that person are not happening to oneself. When one feels compassion towards another, one understands that those bad things really are happening to oneself. Or some such nonsense like that. A pretty waterfall, only a few feet high, distracted me and metaphysics was banished for a while.

I dropped down to the Dosewallips valley and began my climb up toward Hayden Pass, which I would not reach today. I found a bridge over a large tributary of the Dosewallips and had a sit for lunch. Hot fennel salami, smoked almonds, and dried cranberries were almost ideal. Brie, sourdough, and a bottle of red wine might have been more refined, but I had none of those things at hand and didn't really miss them very much.

Up and up the trail climbed, passing through large stands of virgin fir and pine forest, the rainforest left far below. Eventually, nearing my destination, the trail ran out into a meadow stocked with Indian Paintbrush and Lupine, along with that mystery plant that smells slightly like I imagine a rotting rose would smell like. It is omnipresent in the subalpine, and is a smell that I really like. I just wish I knew what threw it off. Mount Fromme sat in the distance, snowless but still pretty. It formed the northern anchor of Hayden Pass. The southern anchor I would climb tomorrow morning.

Clouds swept in, obscuring the mountains, but never really threatening rain. That was good, because the shelter at Bear Camp appeared to have seen better days. Perhaps in 1960. The holes in the shingled roof were too many to count, and of the four sleeping places, only one was really viable. All had a healthy collection of mouse droppings. I brushed clean one sleeping pad and told myself that it was unlikely that I would contract Hanta virus tonight. Things were going just too well for that to happen.

As it was only 5, I stripped down to my shorts and found some flowers to lay in for a while. Work on my tan when the sun occasionally peaked out from the clouds and enjoy a cocktail (straight 120 proof rum). I finished off The Symposium while laying in the flowers, but never really did get much of a tan. I had hoped to blend the lily white skin on most of my upper body with the bronze color of my face, neck, and hands, but the weather just wasn't cooperating. I took another slug of rum and got dressed for dinner.

Dinner, incidentally, consisted of a noodle package that I got at the local discount supermarket. Covered almost entirely in Chinese characters, it had just enough English on it to direct me in its usage. I thought some of the words promised a bit more than the noodles could possibly deliver. I was right.

Dinner done, nothing to do but swill rum and read Abbey. Occasionally swat at flies and microbugs. Abbey on a desert isle in Mexico. Abbey and his wife in the Sierra Madre. Abbey visiting Australia. Abbey unhappy with someone. And, always, Abbey drinking something alcoholic. The sun got far enough down to sleep. I curled up into my sleeping bad and tryed to define and differentiate idleness and idyllic. As always happens when you try to define such things, it led back to happiness.

My position in the valley kept the sun off of the shelter until 7 am, which kept me in bed (not idleness, mind you), snuggled deep within my cocoon of down far longer than I had planned. I boiled up tea and sat in the sun, wondering what today might bring me. Two thousand feet of vertical to the pass, then another 700 vertical to the top of Sentinel Peak. A long walk down to the Elwha. Up to Chicago camp. Those were the destinations. The important stuff happens in between, I reminded myself.

Shortly after leaving camp I was able to spy Hayden Pass and Sentinel Peak. No problem there. Just a big choss heap. Flowers danced in the slight morning breeze, throwing their smell to me and me alone, I mused. Marmots ran about eating flowers, never straying far from their dens and keeping a healthy distance from me. Wise marmots, as I've always wondered how a stew made from such an obese creature might taste. I flung the mandatory insults toward some of them and laughed at the way they scattered. This must be how a grizzly feels when he runs into a human.

I picked up some extra water from a snow stream, as my guidebook warned me that the other side of the pass was very dry. A few switchbacks and twenty minutes of sweat got me to Hayden pass, which I completely ignored for the higher vantage point of Sentinel peak. This was almost too easy, I thought, as I walked up the steep talus slope. Just put a little effort in. Don't even have to think about it.

I topped out in about fifteen minutes, stunned by the views all around. In every direction there was something to gawk at. But, before gawking, I had to take a mandatory "summit" photo.

In one direction I could spy Mount Anderson and its glacier system, with huge glacially carved valleys surrounding the massif. As I turned my head my eyes ran across the Bailey Range and Mount Olympus, which predictably enough had a cloud system sitting over it.

I glanced down at Hayden pass and Mount Fromme on the other side. Fromme would be an easy, though slightly longer, climb, err stroll, as well. Some other time. I followed my route up with my eyes, from the last water gathering down the valley that I had started up yesterday. I sat in the sun and rested for a while, not really wanting to leave. I thought about people that would never get to see such places. I wondered if it was compassion or pity that I felt for them, for their loss. There wasn't anything technical to do to get up here. Just use your legs and go for a walk. My thoughts drifted to the past, flowed over them, and left it alone. The recent past had no more traction in my mind, had no power left. It was done and had faded into pictures only.

I wandered back down the talus to the pass and then began the long, 4100 foot descent to the Elwha valley. My guidebook didn't seem to think much of the trail, except for the upper part where I currently was. Open and exposed and with good views, the Hayden Pass trail seemed quite pleasant to me.

Even better than the views were the extensive fields of paintbrush and lupine that graced the upper end of the trail.

Whole swathes of the mountainside were covered in the purple, fragrant lupine that seemed to live everywhere and anywhere.

And then it all ended. Contrary to the guidebook's warnings, there was a lot of water on the trail. Big streams, bogs, messy hiking. And then a relentless pounding of the knees as I sauntered down toward the Elwha. This valley, running straight into the heart of the Olympics, never seemed to have been logged. While dropping down the from the pass, I was began to tire and become wearing. Upon reaching the valley bottom, I was cheered, re-invigorated. The massive, old growth (ancient growth?) trees had so completely sealed off the forest floor from sunlight that nothing lived down here except for mosses and low bushes.

Feeling positively primeval, I wondered why this place wasn't overrun by those looking for something special and not wanting to work very hard to get it. From near Port Angeles, a tourist or day hiker could pick up the trail and hike it, almost flat, for many, many miles. And yet there was no one here. Not even much sign that people had been here. As I walked along I saw a few tracks here and there, but this valley was mostly undisturbed. And being undisturbed was something that I was really into these days. Peace and calm. Tranquility. The Elwha was low, flat, and mostly green and brown. And it was as beautiful to me as the most vaulted, glaciated mountains that the world held. As I was searching for adjectives, I came upon a large mushroom that had recently sprouted up from the forest floor, taking with it a large patch of soil and needles and twigs. Powerful thing, that fungus.

I flowed through the forest without effort and found myself standing in the cool Elwha river, looking down at my feet. I should have been crossing this thing on a bridge, but here I was in the water.

Bridge was out anyways. Camp wasn't far away and I had plenty of time for Abbey. I found a group of people camped next to the bear wires and close to the river, so I backtracked to a trail junction where there was a nice clearing in the duff to pitch my tarp, plus well shaped logs for sitting on and leaning against.

The bugs were out in force, but this didn't bother me much. Just put on clothes, make tea, and then lounge about with a cocktail (the rum thing). I read more Abbey and drank the last bit of rum just as darkness broke out across the land and sleep called to me. I wondered what she was doing back home. I hoped she was having as much fun as I was out here. Doing something she would remember, that would burn a memory into her being for the rest of her life. I hoped.

The sun was out yet again, but I was shielded completely from its rays by the old growth forest all around me. I drank down my tea in the stillness of the early morning, slightly sad that today was my last day in the Olympics. At least for this trip. I was also eager to get back home and move forward on a growth project that I had been thinking about for the last two weeks. And plan the next trip. After packing up I tightroped my way across the river and then began the steep climb up to Low Divide, 1200 feet above me. Steep, but I climbed without effort. Easy, smooth, tranquil. At the top of the divide (not a true pass), I found a pretty lake sitting at the base of Mount Seattle. I had originally planned to climb this thing as well, but the past few days had been plenty full and I didn't need anything more. I had all that I had come to find. Or, more accurately, I had discovered in myself all that I wanted to.

The otherside of Low Divide ran through open meadows briefly before diving into the forested gorge of the North Fork of the Quinault. Dropping rapidly at first, the trail ran through the narrow defile, taking the fastest way down possible. After a ford of the river at Sixteen Mile camp, though, the trail began to mellow and by the time I reached Trapper shelter it was downright well behaved.

I was back in the rainforest now, with the trail roaming up and down over occasional bumps that ran down from high above. I passed many people heading up into the hills and wished them all luck. With no obvious mountains to stare at, I searched the forest floor for smaller things. Pools of water, minor falls. Interesting leaves, stunted trees. The forest was a living thing, and life was important. Spending time inside a living entity, away from the sterility of the concrete and plastic thing we call a city, was important to me. I needed it. And now I could appreciate it. Now that my mind and heart were pointed in the right direction again, working with me rather than against me.

I stumbled out into the parking area where I had left my car, a bit dismayed to be leaving, but also happy. I was moving forward now, no longer stuck in the past. I was aligned.

Logistics

I hiked from the East Fork Quinault Trailhead up the Enchanted Valley trail to Anderson pass. On the other side of the pass the trail becomes the West Fork of the Dosewallips trail. Camp Siberia is a half mile from the pass and is a good, if cold, place to camp. The West Fork trail runs down to the Dosewallips river trail, which I took up to Bear Camp (shelter not recommended) and eventually to Hayden Pass. Sentinel Peak is an easy walk from there. On the other side of the pass is the Hayden Pass trail, which runs down to the Elwha river valley. The Elwha trail runs up to Camp Chicago, where I stayed the night. From Camp Chicago, I picked up the Low Divide trail which runs, predictably enough, up to Low Divide. On the other side of the divide, I hiked down the North Fork Quinault trail back to my car. One could take the longer, more strenuous, and probably more scenic Skyline trail from Low Divide to the trailhead. The two trail heads are separated by about 10 miles of road. I walked about 4 miles of the road and got rides for the remainder. Without the road walking, I estimate that I hiked about 80 miles.

From Lakewood drive south of I-5 to Olympia and pick up US 101. Although you'll change highways several times, it never seems like it. Just follow the signs to Aberdeen. In Aberdeen, you pick up 101 again and head north toward Forks. In about 40 miles, you'll reach the turn off for the south shore road of Lake Quinault. Follow this and stop off at the ranger station to get a permit ($5 plus $2 per person per night - I ran into a lot of rangers on the trail). Keep on the south shore road, which turns to gravel eventually. The road is very well graded though and runs to the the East Fork Trailhead. A bridge about 6 miles from the trailhead provides access to the northshore road and the North Fork Trailhead.