Mount Rainier, Mount Rainier National Park

Disappointment Cleaver

July 14 - 15, 2007

It had been far too long. No one can live in the Puget Sound area and not, at some time, think about climbing Mount Rainier. I had been living in the area for three years and had not yet even tried it. A year ago a trip fell through when my climbing partner got hurt the week before we were supposed to leave. A month ago the weather looked too foul to leave to town. There would be no stopping us now, or so we pretended. We pulled into the parking lot at Paradise under sunny skies at 7 am to find our friend Bob gearing up with a group of new climbers from the Washington Alpine Club that he was taking up to the top.

Below photo courtesy of K. Gallagher

I had climbed Mount Deception with Kevin and Wayne three weeks ago and knew what to expect from them. New to the crew was Pemba Sherpa, who normally goes by the name of Dominic, a friend of Kevin's who had volunteered (ok, was volunteered) to carry our rope up to Camp Muir, the jumping off point for climbs of Mount Rainier along the Disappointment Cleaver route. After going through the standard paper work, we geared up and instantly complained about the plastic boots on our feet and the paved trail underneath. Plastics are excellent in snow, but pain generators on pavement. The Tatoosh range looked appealing, but we had bigger goals in mind.

Mount Rainier was first spotted by a whitey in 1792 when Captain George Vancouver espied it from Puget Sound. He named it after a friend of his, Admiral Peter Rainier, of Her Majesty's Royal Navy, and a combatant on the side of the English in the Revolutionary War. The Puyallup Tribe called the peak Tahoma, or Tacoma, or Takhoma, all of which are variants on "high snowy place" or "abode of waters". The Nisqually people, in general, have similar names. The mountain was first climbed by Hazard Stevens and P.B. Van Trump in 1870 and many others have followed since then. The mountain stands at an official 14,410 feet, as determined by survey-quality GPS units. Incidentally, scientists in days long past got the figure correct to within 30 feet simply by measuring the boiling point of water on the summit and doing a couple of calculations. However, the elevation alone does not convey the true sense of the size of Rainier. Mount Whitney, in California, is higher, but is not an impressive peak. It is surrounded by many other peaks of the same size. Rainier stands out on its own, with nothing big even close. Moreover, the relief of the peak (roughly, the distance from tableland to summit) is more than 13,000 feet, even higher than that of K2, the world's second highest mountain.

The route that we would be taking runs up the south and south-east flanks of the mountain and is named for the prominent rock formation that it traverses: The Disappointment Cleaver. From Paradise, we ascended along the paved trails that all seem to lead to the vicinity of Panorama Point. The first part of the route was easily visible to us: Ascend to the wall in front of us, make a sharp right turn (out of the below picture), and then turn back around on the snow and ascend to Camp Muir at about 10,000 feet.

Below photo courtesy of K. Gallagher

The ascent to Camp Muir is frequently used by people training for other peaks and has a reputation of being difficult. In the sunshine, it seemed rather easy to us, even with full packs on. We did, however, us the blessing of a clear sky to lollygag and rest. A growing cloud on the summit of the peak, though, gave us some pause and an incentive to begin our climb early the following morning.

Temperatures had been warm for the last week and a half and we were a little worried about snow bridges collapsing and getting fried by the intense reflected light. Climbers on Rainier tend to start around midnight to make the slog up in the dark, when the snow is hardest (and strongest), the winds lowest, and the light least intense. The idea is to be high on the mountain by the time the sun begins to rise, and on the summit by 7 or 8 am, before the sun has gotten strong. This way, you can get back down the mountain side, across snow bridges, and back to camp by noon.

The clouds over Rainier had formed into a lenticular, which is a sign of truly awful weather to come. The wispy grey clouds raced over the top of the mountain, conforming to it like a glove. Oddly enough, it was hard to tell where the clouds were coming from, as the skies to the windward side of the peak were clear. It was as if the mountain was creating its own clouds out of its sheer mass of ice.

We stopped for water at Pebble Creek at 8100 feet and watched the Muir Snowfield slowly fill up with people. There were the day hikers in tank tops and tennis shoes. Skiers hoping to get a few turns in. Hikers out for some conditioning with massive packs. And a few people with ropes strapped to their backs, as our faithful Dominic was, intent on climbing the most heavily glaciated peak in the US outside of Alaska.

The Tatoosh, which had looked so impressive from Paradise, seemed like a little range of pimples as we broke through the 9000 foot mark. The deep valleys below began to hold the traditional summer haze, which seems to be a naturally occurring, instead of man-made phenomenon. Mount Rainier National Park was created in 1899 to protect the obvious natural worth of the area. Unfortunately, the park contains the peak and a small amount of land immediately around it. The area outside of the park is owned partly by timber companies, and the rest by the people of the United States, who allow it to be administered by the US Forest Service. However, the Forest Service, at least at one time, allowed the lands to be heavily logged. The result is an island of preservation. Islands are not good for large eco-systems.

As we neared Camp Muir, we also neared the clouds. A heavy wind was blowing across the collection of buildings that marks Camp Muir, bringing with it a chill that was not present on the snow field itself. Camp Muir is a rather well developed area, as it would have to be given the number of people who visit it each year. It is a destination for skiers and overnighters in the winter time, climbers in the summer, and hikers year round. There is a permanent ranger hut, along with several other facilities for employees of the government. There are huts for the commercial guiding operations on the mountain. There is a hut for regular climbers. There are several privies. In short, Camp Muir is a small town, lacking only a Starbucks. This, however, will surely be added, when the Park Service begins to seek out new revenue streams in an attempt at "continual improvement."

The National Park Service is an odd agency. It is tasked with protecting and preserving the natural crown jewels of the United States, of which there are many. The US has, perhaps, more natural wonders than any country on Earth, and certainly the most accessible public lands. However, the majority of users of our National Parks are front country tourists. Front country tourists cost money: Roads need to be maintained to a high standard to allow RVs to drive in and for passenger cars to drive all over. Trails to popular destinations need to be paved and roads built directly to them, so no one has to sweat for more than 5 minutes. Massive visitor centers need to be built so that people can visit the park without actually walking anywhere and yet still learn something of the natural and human history of the park. And huge inns need to be built so that people can stay in the parks and not sleep on the ground or give up any of the comforts of home. These are the majority of users.

All of this costs money, and park entrance fees do not cover all the costs. That is, the parks are not self sustaining entities; they depend upon additional funding from the government, which is traditionally tight fisted with its funds. And, acting as a good corporation should, the majority of the money goes to the majority of the users. That is, it stays in the front country. The road to Paradise, which was severely damaged in the storms of November 2006, is rebuilt. The huge new visitors center is being built. A massive inn at Paradise, and at Sunrise, are being built or reworked. And the trails damaged in the storms? Another time. Not enough money. The Wonderland Trail? The jewel of the national park? The opportunity to experience all that the mountain has? Maybe next year. There just isn't enough money to hire enough brute force labor to rapidly rebuild things that don't bring in revenue.

Below photo courtesy of K. Gallagher

But there are some things that are more important than revenue streams, and there are some things that are lost when people are encouraged to stay only in the frontcountry, when the backcountry is given secondary status. There is a belief that overuse will occur, that rescues will increase, and that, paradoxically, fewer people will be able to enjoy the park. I would argue, however, that building a new inn does not serve to promote anything important in the park. One need only look to Yellowstone for guidance. Our oldest national park is nothing but an auto-touring plaza, complete with jails. The park had a small contingent of climbing rangers who did their best to help climbers enroute and rescue people in difficulty. They work hard and have many different problems to deal with. They are underpaid for the skills they bring to the table and the work they put in. It would seem a simple task to hire more, but the funds are not there. The funds are going to things like the new visitor center and the new inn. The NPS seems more willing to invest in capital projects that are things, rather than putting the money in to human resources.

Below photo courtesy of K. Gallagher

We arrived at Camp Muir at noon, a little over four hours after setting out and began the process of acclimating ourselves to the comparatively thin air of 10,000 feet. This mostly involved sitting around in the sun and watching climbers slowly roll in, but occasionally meant a more strenuous activity, such as drinking soup and ogling an especially attractive climbing guide of the female persuasion for RMI, the chief commercial service on this side of the mountain. For a mere $800, not including equipment rental fees, RMI will walk you up to the top of the mountain. For $30, the cost of a climbing permit, we were doing the same thing.

Below photo courtesy of K. Gallagher

RMI, however, played a very active role in our own try for the summit: The RMI guides set and wanded the route as it weaved through the crevasses. Their effort meant that the climbing rangers didn't have to do it, and kept us on safe ground without having to put effort into it. We could just climb and not have to route find. By 6 pm I was in my sleeping bag, ear plugs in place, trying to get some sleep before our scheduled wake up at midnight.

Below photo courtesy of K. Gallagher

The first I knew of the wind was from the blasted climbers who came staggering in just after midnight. They had been thrashed by it on their summit bid, which they left for at 8 pm. Kevin, Wayne, and I debated the wisdom of even leaving the hut. The wind was strong enough to move you around with ease, which isn't such a good thing if you have to dodge crevasses. After much discussion, we geared up and were moving by 2 am. We traversed the snow to the rubble of Cathedral Gap, where the 50 mph winds brought stinging particles of sand and grit onto the little bits of skin that we had exposed. We met a party of climbers who had been turned back by the winds, and talked amongst ourselves for a while longer.

Below photo courtesy of K. Gallagher

We forged on through the gap and down to the Ingraham glacier below, where we met another party of climbers returning to Camp Muir after a failed attempt. Roping up, we ascended and crossed the glacier to Disappointment Cleaver, jumping some gaping crevasses enroute. Another party was returning from the fierce winds, which had nearly blown them off the top of the cleaver. Later, NPS weather data would show that winds were blowing at a sustained 40-50 mph, with gusts up to 65 mph. Scrambling up the cleaver in crampons wasn't much fun, and I was quite happy to take to snow again near the top of the cleaver.

Below photo courtesy of K. Gallagher

From the top of the cleaver the route is normally fairly direct: Go straight for the summit along the upper Ingraham glacier. This year, however, the glacier had broken up in a strange way and crevasses were forcing climbers to traverse far over to the Emmons glacier, where conditions were more favorable. I sucked down another packet of gu as we rested on top of the cleaver, knowing that there wouldn't be much more protection from the wind. For here we had some shelter from the howling winds. Above, there would be no more.

Below photo courtesy of K. Gallagher

The sun was coming up, illuminating the world below us. Although stunningly beautiful, the light also revealed the world above us, and we could see a thick mass of grey clouds whipping by the summit. The ascent would not be easy.

Below photo courtesy of K. Gallagher

We had been warned that there were some tricky crevasse crossings just after the cleaver, but these turned out to be easier than expected. The "six inch" snow bridge turned out to be several feet wide, and the only danger was getting vertigo from looking into the depths of the crevasses below. In the pictured below, I'm walking down to the snow bridge that exits the pictured on the middle right, not following the rope.

Below photo courtesy of K. Gallagher

We crossed the difficult crevasses and traversed far over to the Emmons glacier, where we met our first successful party: They had left at 9 pm and summitted at 7 am, and were now on their way down. We talked briefly and then continued up, breaking the 13,000 foot mark with some rapidity and just before reaching the racing grey mass above. Little Tahoma, a mountain that looks imposing from the White River, far below, seemed a little pimple from this vantage point. It is the third highest peak in the state.

We all felt strong, though tired from the elevation as we plodded up the well worn track toward the summit. Perhaps twenty successful climbers passed us on the way down. You could tell the ones feeling great from the ones feeling sick by how much they said. The tired ones said nothing. The ones that said hello, or another word or two of encouragement felt ok. The commercial guides had loads to say. Slowly we reached the rim in a gale. Indeed, the gale had been present since breaking 13,000 feet . Reaching the top at 9 am was rather anticlimactic: Rather than a well defined summit, there is instead a crater rim. The highest point is a small knob across the crater. As we walked across the crater, I realized how mentally unattached I had become. Physical tasks became difficult. I almost vomited twice on the walk over. A minute short of the true summit, I told Wayne I was going back. I wasn't sure why, but given that I later would spend twenty minutes standing in the full blast of the storm, shouting at it, I don't think I was in the best mental state to make decisions.

Below photo courtesy of K. Gallagher

After an hour on the summit, and in a complete whiteout, we re-geared and headed back down the mountain. There was no one on their way up. There would be no one around if we got in trouble. At such times, it is best to stay out of trouble, which means being careful. Being careful when tired is difficult, but as we descended the oxygen got thicker and it became a tad easier to move about. Many people get hurt, or die, on big mountains not during the ascent, but during the descent.

Below photo courtesy of K. Gallagher

There is a rush to get back, to get down, to get to some place warm, that causes lapses in judgement and makes you take unnecessary risks. Despite our weariness, we moved cautiously down the Emmons and back through the crevasse crossings to the cleaver. Fortunately, the RMI folks had kicked out a new descent route on the cleaver which took snow almost the entire way. With wands to mark the way, the cleaver turned out to be easy and we were soon near the base of it, with clearing skies.

When we had passed through this morning, there was nothing but blackness to be seen. Now, the world of Ingraham Flats, with its huge crevasses and little tent cities, was spread out below our feet. In the below photo, you can see two clusters of tents, one in the center-left of the photo, and the other down and to the left of that. Our route from Camp Muir can be seen coming from the low gap in the middle of the picture and running from left to right (out of the photo), and then back to the cleaver. The large crevasse in the lower right of the photo is near the route.

We rested for several minutes at the base of the cleaver before setting out for the last little walk back to Muir. We were tired and moving slowly, and moved snail like along the boot track. One of the tent cities was packing up and leaving, apparently guided by one of the non-RMI services on the mountain. Ingraham Flats was definitely a prettier place to camp for the night, with Little Tahoma looking much less pimple like from down here.

Finally we exited the glacier and unroped, for the scramble over Cathedral Gap. As if to punish us one last time, the mountain sent a squall powerful enough to bring for cries of pain from the three of us from the grit blasted in our faces at 80 miles per hour. Once on the other side the squall stopped and fifteen minutes later I staggered inside the shelter. Amusingly enough, there were a group of college students in shorts and sweat shirts who had walked up to Camp Muir and were now sitting where we had left our sleeping pads. I stripped off my boots to left their full funk penetrate the noses of the students, considered stripping naked, but settled on slumping on top of my air sleeping pad, which had been graciously vacated by the students.

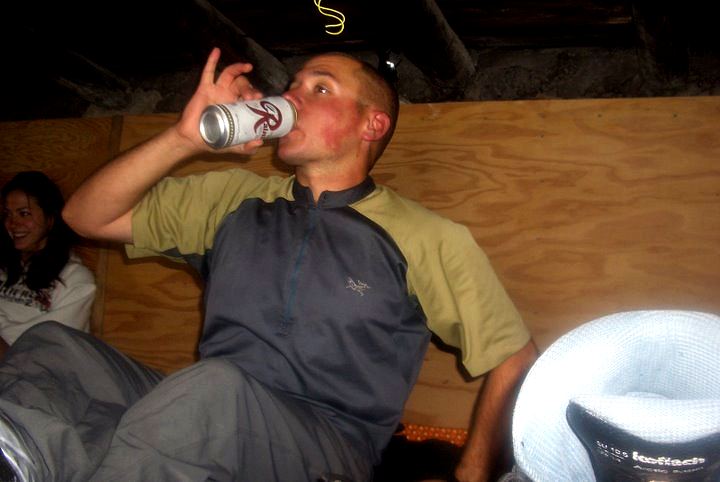

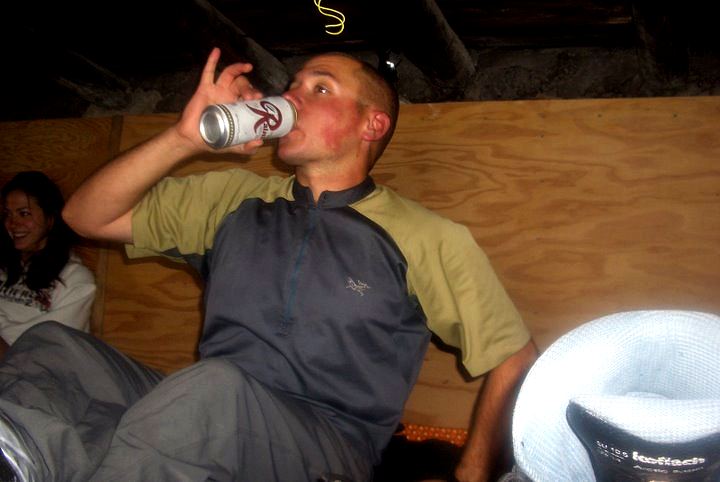

Below photo courtesy of K. Gallagher

A celebratory swig of beer brought the expected results.

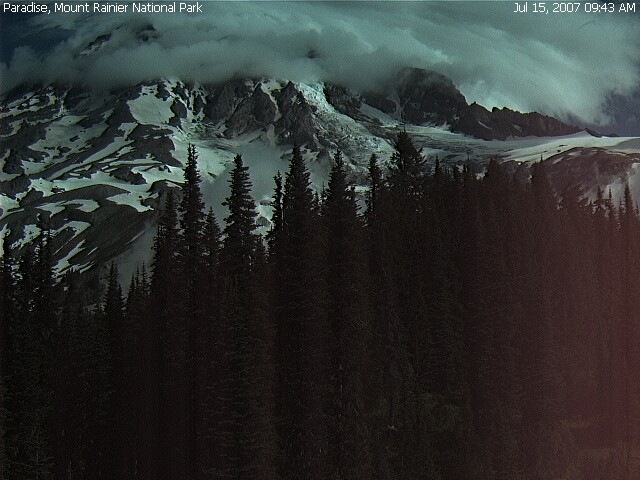

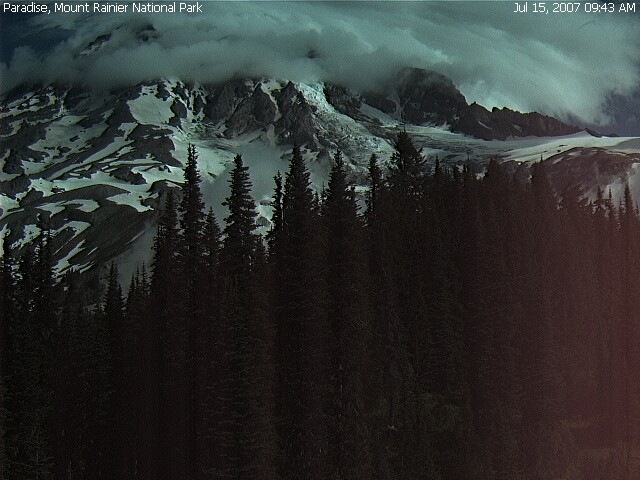

Below photo courtesy of K. Gallagher

We would return to Paradise and the ride home in two hours, and later a friend would send me a photo of Mount Rainier taken from Paradise around the time we were summitting. As awful as the weather had seemed from up high, it was even worse when viewed from down below. I try not to feel much pride in things that I do, but knowing that we had climbed through the storm caused a definite rise in my ego. Perhaps that is why people climb Rainier: You have really done something.Rainier is a big mountain, and the storm a violent one. We had persisted, summitted, and returned safely. It wasn't an aesthetic climb. It was a challenge, and one that as a group, and as individuals, had met.

Below photo courtesy of the NPSr

Logistics

From Lakewood, take SR 512 east to SR 7 and follow the signs directing you to Paradise. After passing Alder Lake, reach the town of Elbe and take SR 706 to the Nisqually entrance station of the park. Unless you have an annual pass of some sort (Golden Eagle, for example), you'll need to pony up $15 at the entrance station. Follow the road past Longmire and up to the Henry M. Jackson Visitors Center at Paradise. Behind the visitors center you can take a variety of paved or gravel trails that will get you to Panorama Point. Continue on the trail to snow, and run the broad snow straight up to Camp Muir, which is a collection of stone buildings and tenting sites. The trip up will take between 3 and 6 hours depending on conditioning and loads (it took us 4 hours and 20 minutes). If you don't want to tent, you can stay in the shelter, which is quite nice but can be crowded. Moreover, space is first come - first served.

Depart Camp Muir early. Most groups leave around midnight, while we left at 2 am. The route will be fairly obvious if you go in prime season (mid June to late July) as there will be a well established boot track. Traverse across the snow to Cathedral Gap, which doesn't look much like a gap. Rather it is a ridge of dirt, dust, and rock which looks worse from afar than it actually is. Drop down the other side to the Ingraham Glacier. Rope up here as there are crevasses. Ascend the glacier for a bit to Ingraham Flats (camping here as well) and then traverse across to Disappointment Cleaver, which is the big rock staring at you. Ascend the cleaver, either on rock or snow, depending on the conditions you find. The top of the clever is 12,300 feet and is where many parties turn around due to altitude related problems or exhaustion. The route from the top of the cleave varies from year to year depending on what the glacier is doing. In 2007, you had to traverse to the Emmons Glacier (way out of the way) and then ascend that to the top. This was much longer than usual. It took 7 hours, 15 minutes for us to reach the summit, and five hours to descend, but this involved a lot of dickering around and talking to parties that had decided to turn around. The descent from Camp Muir to Paradise takes about 1.5 hours.

To climb the route, you should be in good shape. If you are not, it won't be much fun. If you are in shape, there are no technical difficulties involved in reaching the top: Just keep plodding on snow and rock and make sure to follow the wanded boot track. One way to know if you are in shape or not is to hike up to Muir. If you think it is at all hard, you are not in shape. Remember to eat a lot, especially while climbing. Make sure to drink lots of fluids at Camp Muir, as adequate hydration is key to warding off altitude related problems. Altitude problems can include severe headaches, nausea, mental discombobulation, rapid heartbeat, shortness of breath, and worse. High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE) and High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE) can strike climbers and kill them, even at this (relatively low) elevation. If you vomit, it is time to turn around. Listen to your body and don't try to be a hero, unless you really want to be a statistic. Bring plenty of fuel and a stove to melt snow into water with. Make sure to rope up and know how to rescue someone out of crevasse if necessary. Know how to use an ice axe and how to self belay. Knowing how to self arrest is important as well, but know that it is a last resort and may not work (i.e, you're going to die if you fall and can't stop immediately). Crampons and an ice axe are mandatory.