Drift No More

Port Townsend, WA to The Pacific

August 22, 2008

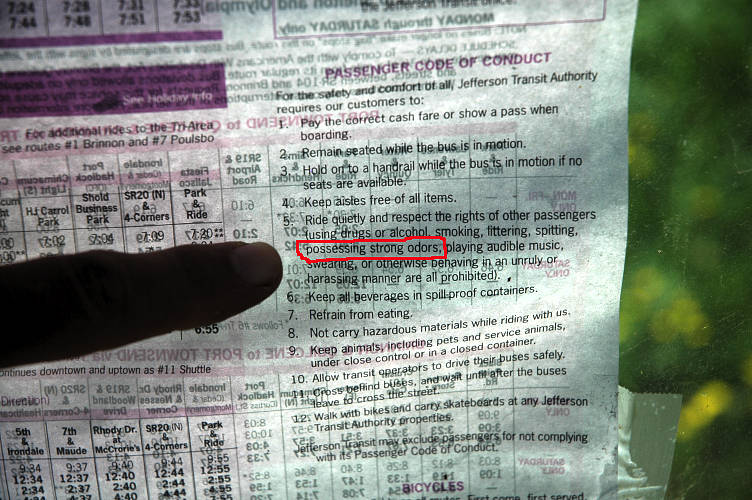

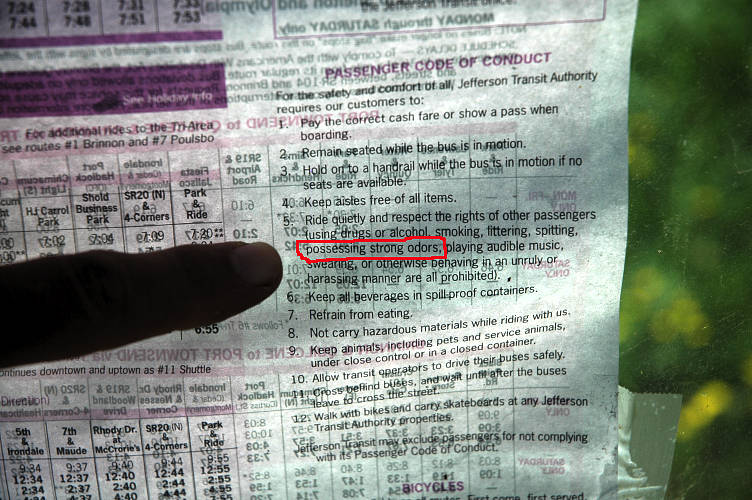

I was up early and found a new tent had sprouted up next to my tarp. I had been drinking beer in the dark when they came in last night and started setting up without headlamps, as quietly as possible. More homeless, no doubt. I walked back into town via a slightly different route, eating blackberries as I went, and made a stop at the Safeway for two pastries and some yogurt for breakfast along with a large coffee from Whorebucks. My route to the Olympics was not one I had been looking forward to, and it eventually fulfilled all of my expectations of it. I wandered down SR 20 before cutting over on Discovery Road, which for some reason (the guidebook) I had thought would be a quiet, pleasant country lane. Instead it was a major commuting road with a small shoulder, high speed limit, and a lot of trash. There was, at least, some interesting garbage.

Since no one had a trashcan out for me to use, I stuffed my empty inside the mailbox of a particularly wealthy looking abode, picked some blackberries there, and moved on while listening to NPR and hoping a car wouldn't hit me. The route was a stupid one, for in just a few miles the official PNT was a bus route down SR20. If I was going to get on a bus anyways, why not just do it in Port Townsend and avoid the nasty, dangerous road? I suppose I would have missed all the berries, though.

The sun came out for once and the weather was generally fine for my walk along the depressing road. There were a few views of the bay, but these rapidly went away and were where the shoulder was worst. At a golf course a little rat dog ran away from its owner as he was lining up a shot and yapped at me. I chased it off only for it to come back. The owner didn't seem to care in the least. I chased it away again, but it came back again, trailing me down the road, barking and barking and barking. The owner still didn't do anything, which perhaps was reasonable as we were now a hundred yards or more from him. I started to get angry with the dog, who was still barking and chasing me as I walked down the road. Finally I chased the dog for real with the intention of throwing it under the wheels of a passing car. The dog, perhaps sensing the murder in me, ran away and didn't come back.

I arrived at a spot on my map called Four Corners where there was a gas station and a bus stop. It was here that I would catch the bus, which would be coming from Port Townsend, to Discovery Bay, where the PNT's circuitous route into the Olympics left from. While looking at my map and reading the cryptic directions for how to follow the route, I decided that it would be better to simply ride the bus for another few miles and walk directly in via Palo Alto road, which I had driven many times. Besides being easier to find, the PNT hits Palo Alto road eventually! True, I would be on a road a bit longer. However, Palo Alto actually is a pleasant, country lane and would be a fine walk, which Discovery Road certainly wasn't.

One bus rolled up and disgorged its passengers, all of whom looked to be at the bottom of the socio-economic scale. The stop filled with people and when I got on the bus eventually it was standing room only. I started feeling self conscious, both because of the pack on my back and my generally poor state of grooming. The people on the bus were poor. The conversations I heard ranged from who was in prison to how "hard" Mario's crew is. I got off ten minutes later at Discovery Bay. I just didn't want to be on the bus anymore. It was silly, but I didn't want to spend any more time on it than I had to. I stopped in at the store for a soda and then headed down the PNT, which was actually Salmon Creek Road. The weather was bright and sunny and I had an excellent view of Mount Baker on the other side of the Sound.

Far down the road there was a man on foot, walking away from me. I'm not sure if he was the cause, but soon after I set out on the road a terrier came trotting down a driveway, looked at me for a moment, and then kept on in the direction of the man. No barking, no yapping. Not so strange, but then a cat, an orange tabby to be precise, came down another driveway to greet me. I petted the cat a few times and then continued down the road.

The tabby followed me, running in front at times, and at others dropping back. I wasn't sure if the cat was tagging along with me or following the man out in front. I've had dogs follow me, sometimes for days, but never a cat.

Salmon Creek road ran on past a few farms and the cat eventually turned off at a lane where presumably the man and the terrier were walking. Only a few minutes further along was a large house on a hill with a PNT sign for me. It wasn't an official sign by any means and it was clear the landowners were fans of the trail. This was only the second sign for the PNT that I had seen, the other being off of Chuckanut Drive near Samish Bay. It was a big event for me and I took a photo to mark the occasion. And then I heard the dog.

The dog was trotting toward with a serious swagger and hostile intentions. The barking was vicious and, when he got close, I could see the hair on his back standing on end, like a mohawk down the spine. I didn't know the breed, but it was clearly not a mutt, nor something that I'd come across before. It weighed in the neighborhood of 60 pounds, which meant that if I did have to fight the dog, I'd eventually win. The PNT, according to the sign, went right past the house, traversing the dogs homeland, which it would naturally feel inclined to protect. I stood, facing off the dog, trying to charm it. My dog radar told me that this was a guard dog, rather than an angry dog or a bully dog. The dog would protect its home if it thought I was a threat to it, which meant that I could get by, hopefully, without a confrontation.

The dog calmed several times and stopped barking, but whenever I would take a few steps along the lane it would go back into aggression mode. My efforts were failing and as I got further up the lane, inching slowly forward with my hands open and talking in a calming, soothing voice, the dog became more incensed, reacting to me with more visible signs of impending attack. The mohawk was as sharp as ever. Teeth barred. Tearing at the ground with front paws. Springing around rather than walking. The confrontation had been going on for fifteen minutes and I had managed to slowly get down the lane and was nearing the house. If the dog was going to attack, it would be here. Once I moved beyond the house it wouldn't be a problem. I thought about picking up a heavy stick and simply beating the dog into unconsciousness, but this would look pretty bad for the PNT if the owners figured out who did it. I also didn't want to do it because I felt the dog and I would have been friends if there had been someone around to introduce us properly.

Slowly I moved forward. I was aside the house, my eyes on the dog looking for the start of an attack. It kept itself between me and the house, finally ceding the lane to me. I moved more rapidly now. The dog followed as I walked backward down the lane, barking and snarling, but within thirty feet it stopped and simply watched me go. I walked up the lane, following a mown strip through the grassy field and followed the signs that the landowners had put up for hikers.

The route quickly went into the forest and then started traversing along ATV and ORV tracks to get to the logging roads I was heading for. The PNT takes an odd collection of these roads into the national park itself and I had hoped to avoid them. I've got nothing against walking roads, but logging roads are generally not marked and change frequently. With relatively complex instructions for how to navigate these, my hopes were not high for the immediate future. I broke into the open and enjoyed the views, passing a variety of roads along the way, none of which were on my maps. The guidebook description ceased to make any sense and the views that the author described simply were not there. I used the usual route finding method of following the biggest road and hoped for the best. Something good usually happens.

In this case, what happened was that the road climbed when it was supposed to be flat and then simply ended. By ended, I mean that it simply went no further and I had only forest in front of me. I wasn't sure what to do, but I spied what looked like a little path heading off to the right and so I wandered that way, which was in the general direction of where I thought I wanted to go. Forty minutes later I stumbled back out of the forest, thankful to have found my way back to the road, and took a self portrait of a very unhappy hiker.

I had only wandered a hundred feet from the road, but then managed to get completely turned around in the forest. It was so thick that I couldn't see the road at all and ended up walking in circles until I finally found my way out again. I read and re-read (my twentieth time) the description in the book and looked at my maps. I had no idea of where I was, so I walked back down the road for forty five minutes until I was able to place by location at a significant water source that I could only hope was Salmon Creek. If it was, then a hundred yards or so in front of me was where the PNT diverged. I walked up the road, looking for signs of anything. I eventually found it: A bit of flagging tape on a branch and some ATV tracks running down into a muddy culvert and then up into the forest. That was it. Easy to miss. Why the PNT didn't just go to Palo Alto road on the bus in the first place was beyond me. I followed the muddy ATV track through the woods to an abandoned logging road, which led to a good looking road heading up hill. The route description wasn't entirely clear if this was my road or not. I was frustrated with everything and everyone and the normal serenity that I experience in a quiet forest boiled away in anger. I stormed off and thankfully hit the correct road not much further on.

I cooked diner not much long after I reached the big, actively driven road that would take me to Palo Alto road. Some enterprising hiker had built a sign of sticks in the roadway and I admired the workmanship over a potful of macaroni and cheese. It was one of the only bright spots for me during the day and I was thankful for it.

A few more miles got me to Palo Alto Road, but only after I had to threaten two more dogs who thought they needed to run out into the road and bark at me. I was glad to get to the road, which I should have just taken the bus to as I had planned to. The valley was well lit by the early evening light and there were no cars and no barking dogs. It was just quiet and peaceful and serene, everything that had been lacking in my day.

The Olympic Mountains are not a single chain of peaks running in a common direction like, say, the Sierra Nevada or Cascades. Rather they are a collection of several groupings separated by deep valleys. It is possible to cross through them by walking the near-sea level valleys and going over one pass of a modest 3,000 foot stature. I was walking up one of these valleys currently, though outside the park, and tomorrow would climb into the high country.

The fact that I didn't have a permit for the park didn't bother me at all: You only need a permit to camp overnight in the backcountry, not to go for a walk. Besides, I didn't like the idea of a needing a permit to access my own land and certainly wasn't going to pay money for walking across it. A very large part (all) of the trail maintenance is done by volunteers and certainly not by park rangers. I'd be camping outside the park boundary tonight anyways, and tomorrow I'd camp in a front country campsite where, if anyone asked, I'd tell them I had no money to pay for a site.

Palo Alto road led me past the farms and eventually into the forest once more, where it dropped down to meet the Dungeness River. There was a national forest campground here, but it was filled with cars, despite big signs saying that there was no water here. The massive river, running right next to the sign, seemed like water to me. After passing through the campground to make sure there were no open spaces, I went off into the woods and with the last bit of light managed to find a place where I could set up my tarp and camp for the night. The ground was soft and made for a perfect bed; much better than anything inside the official campground. It was free and it was legal. I was on my land now, and as long as I followed a few basic rules common to all I could camp where ever I pleased for up to 14 days. After that I would have to move to some other spot. The deep smell of the rain forest, for that is where I was, was intoxicating after the roads I had been walking for the last few days. Sleep was not long in coming.

I slept deeply, more comfortable on the soft duff of the rainforest floor than I would have been in any hotel bed in the world, no matter how soft or smooth. The smell of the earth, the forest, the shrubs, myself, these things all seemed to be comforting to me. I brewed up a pot of tea and sat under my tarp looking at the green world around me, happy that I was here, but also pleased that I would be climbing into the alpine today. I had fun stuff in front of me for the next few days, which made the steep climbs of the Olympics seem non-important.

This, at least, was how I felt in the morning before I started sweating and working. After breaking down camp I followed the road as it climbed steeply, then dropped just as steeply to the Dungeness River, next to which I had slept. It was only 7:45 and I was already full lathered! Just beyond the crossing of the river I found a large, open trailhead, but no signs indicating the Grey Wolf River trail, which I was planning on following into the park. I poked around a bit and found a large, well built trail at the back of the parking area. In the absence of any better option I followed it up and into the forest. It was not long before I entered the Buckhorn Wilderness, one of the four petite Wilderness Areas that sit on the boundary of Olympic National Park.

The Olympic Peninsula was one of the last explored areas in the contiguous United States and large portions of the interior were not completely understood and mapped until the World War II era. The topography is very difficult and the rainforest growth too thick to allow easy travel. Despite the proximity of Seattle, Tacoma, Victoria, and Vancouver, very little was known about the mountain ranges, even by the local Native Americans, who mostly roamed the coastal and foothill regions of the peninsula. There were, of course, exceptions, but one reason for the lack of explorations by Europeans, Americans, and Canadians was the fact that no natives were around to show them the way.

My trail led me to a potential ford of the Grey Wolf, which didn't seem like a good idea to me. The bridge that used to be there had washed out a long time before and the Forest Service had not seen to replace it. There was a downed log that served as a skinny and scary bridge to the other side. I tight-roped it and bushwhacked over the the trail, which began a relentless climb up the hillside. As I gained elevation the rainforest slowly morphed into fir and pine lands, with new smells and sights. But I was tiring as I gained elevation and my mood was beginning to drop. My feet hurt. My back hurt. I was tired of being sweaty all the time and of having to swat mosquitoes and flies and to pull creepy-crawlies off of me. I hoped I would feel better later. I entered the park at a sign that I really liked.

I have a love-hate relationship with our National Parks that is pretty simple and easy to understand. I love the parks and the park system. I hate the way they are managed, funded, and staffed. The parks are for the people, right? Well, it now costs $15 to drive a car into the park, and because there is no shuttle system in place, you have to drive unless you have a lot of time on your hands. There was a proposal not too long ago to raise the fee to $25 but people complained enough that the Park Service relented. Suppose you want to camp in the backcountry. First, you need to pay $5 for the permit. Then, $2 per person, per night. While very reasonable by Park Service standards (check out the Grand Canyon fees), the price starts to add up. Sure, I have a job and can pay the fees (I don't), but I also know a lot of really poor people for whom that $22 (to get in and camp for the night) represents their entire food budget for two or three days. They'll never be able to legally go to the Grand Canyon, where I have to pony up more than $50 to get in and camp for a few nights.

I reached the confluence of the Grey Wolf, Cameron, and Grand Rivers and started the stiff climb up toward the alpine region of Deer Park. But, I must continue my diatribe about the parks. Simply put, I do not think the Park Service is using the funds it receives in a manner consistent with its mission of preserving and protecting America's natural heritage and keeping pristine places pristine. The NPS seems dedicated to increasing the number of people who visit frontcountry sites in their vehicles, and hence are easy to manage and herd, rather than promoting responsible backcountry travel by those on foot or horseback. The evidence is very clear and I'll cite an example to show it: The NPS spent $40 million to renovate the Paradise Lodge at Mount Rainier, and it isn't even open year round. Yet they can't even manage to put up ski and snowshoe blazes on some of the common routes in the forested lands. They haven't yet managed to fix the damage to the Wonderland Trail, a premier footpath around the mountain, from the storms two years ago. Is there a shuttle running through the park so that hikers don't have to drive or try to form loops or hitchhike? Why not? Because it, and the Wonderland don't, in the eyes of the business oriented managers, do anything to raise revenue. A free shuttle or, gasp, a nice trail, will be a perpetual money sink, whereas they might have some hope that the money spent on the lodge will eventually pay for itself. Moreover, they reason, most people just go to the lodge, so why don't we make it super nice for them?

My mood steadily improved as I climbed and left the pines and firs for the subalpine scrub and its attendant views of the distant mountains. I had climbed and tramped through most of them on various excursions in the last four years, though many I had not yet gotten to see from up close. The climb was stiff but the air was pleasantly cool at the higher elevation and I had more to look at than just the trees.

And so what should be done about the parks? Rather than complain about them, I've got some constructive comments. First, parks should be free. Period. Free to enter, free to camp in, free to enjoy for all people. This is our national heritage, not Disneyland: Let people in clown suits charge a family $300 for a day of agony. Second, cars should be kept out and a shuttle system put into place on the roads so that people can get to the more distant parts of the park in a reasonable time frame. Bikes can be provided at the entrance so that hardcases who don't want to ride can bike. Besides being beneficial to the local fauna, the air will get cleaner and people will be happier not to be in traffic jams caused by a coyote sniffing at a bird carcass by the side of the road. Third, rangers need to be in place to do more than harass people about campfires and picnic coolers: The programs they lead in the backcountry, frontcountry, and their patrols need to be expanded so that more people can learn about the natural world around them and, in many cases, in their backyards. For people used to the outofdoors there is no fear about showing up to a place and going for a hike. But what about an inexperienced family who wants to see a few sights? Or a homebody who wants to learn what flora and fauna there are? This means we need to invest in people, not in things like new buildings and roads.

Note that none of my suggestions generate revenue. They are not self sustaining. Like the military, we need to make a conscious decision that the parks will be a priority for us and that they will be managed in such a way that the people, and not their machines, will benefit from them. Spending money on improving the auto touring route of Yellowstone National Park does not do this. Did you know that there is no shuttle system in Yellowstone? In America's first national park, and still the premier wildlife park in the contiguous US, there is no option other than hitchhiking if you happen to be on foot.

Ok, my diatribe is over. I made it to Deer Park where a front country camp ground was located. Just before I got there I passed through a small burn area that had recently been re-cut. Compared to the burned areas in the Pasayten, this was almost cute in its petiteness. But the views from Deer Park were just phenomenal. The Olympics are not high mountains, but strong storms come off of the Pacific and the Olympics are the first thing that they hit. As a result, 5000 feet in the Olympics gets you into the alpine. I was so excited for tomorrow because I knew that I had a long traverse that was far above 6000 feet. It was going to be good.

The campground was remote, accessible only by a high standard gravel road that RVs couldn't, or shouldn't, drive up. It was also crowded. I wandered around looking for some information and finally found the two "on foot" campsites. Complete dumps, with very slopey ground which was pure dust where they were not covered by downed trees. The drive in sites looked very appealing and were well manicured. Pretty typical. I pitched my tarp in the best spot I could find. If it rained, at it looked like it might, I'd be swimming in water and mud.

I wandered out to look for water. None of my neighbors in cars knew if there was a water source nearby: They had brought all of theirs from home, where the water was safely treated and wouldn't hurt their delicate systems. I ignored the sign asking for $10 for the night. If some one asked, I'd claim to be homeless and not have any: Where would they send me? Without a car I couldn't get anywhere else, and the closest backcountry campsite was quite a ways away. I walked over the ranger station, inconveniently located about a quarter mile away and rather steeply down a side road. A sign on the door said the ranger was out, but the truck was still in the drive way. I located the ranger's water supply, which was running from a spring that they had made completely inaccessible to anyone via a pipe. I ended up stealing a bit of water from a leak in the pipe and returned to my camp to have dinner, a bit down in the mouth.

I cooked and ate dinner while listening to one of my favorite radio programs from back home, "All Blues" by KPLU, the local NPR station. I was enjoying the music and the fact that neither ranger nor campground host had come to shake me down for the $10 (same cost as for the car campers and their vehicles). What I wasn't enjoying was the weather report. A storm was coming tomorrow and was expected to hit the Sound region in the early afternoon. That meant it would be here around noon. Maybe it wouldn't be so bad, I thought. Maybe it will hold off until you're off of Hurricane Ridge and back down in the safety of the forest, I told myself. It didn't matter, really, I suppose. I knew of the danger and would do what I could to avoid it. If it came, then I would deal with the problems it brought. Until then, there was no reason to worry over it.

i was up early and drank tea quickly. I wanted to get on the ridgeline as quickly as possible. It was going to be beautiful for sure, but whether or not it would be lethal was yet to be decided. The weather was pleasant enough for now, but I had a long traverse above treeline coming and there was definitely a storm system coming. Of course, the camp host managed to find me as I was walking out and asked me how I liked the camp. "Well, its pretty much a dump down there for hikers. The ground is slopey and dirty and there are downed trees everywhere. Its also really far from the water source, which is rather inconvenient for people on foot." Or something like that. He seemed a bit puzzled and said that the rangers had been busy clearing the trail that I come through yesterday. Although I was pretty sure that actual rangers don't do trail maintenance (volunteers and contractors) and that they certainly don't build campsites (volunteers and contractors), and that the amount of trail that had to be cleared was pretty small in comparison to what I'd come across in the Pasayten, I nodded, smiled, and left. My route started near the ranger station (the sign said the ranger was still out) and I got a good view of the start of the ridgeline that I'd be running. After a bit of forest, it turned all alpine.

I couldn't resist ogling the Royal Basin/Needles area, where some of the best climbing (only good?) rock climbing in the Olympics is. Another time. The weather was getting steadily worse, but for now there was no rain and only a gentle breeze to hurry me along.

I dropped down to a saddle in the forest and then began the climb to the top of Green Mountain. I couldn't see the horizon and had no idea what the weather might be like on the other side of the ridge, which is where the weather system might be coming from. There was an odd mixture of joy and extreme apprehension in my blood. If the weather could just hold off for a few hours, I'd have a great hiking day to Hurricane Ridge. If it didn't, I was going to suffer. Yesterday's acceptance had vanished. I topped out and got a good, solid view down to Sequim, Port Angeles, the Straits of Juan de Fuca, and Vancouver Island. And the storm. It was such a beautiful sight, with the strangest glow of green and blue, that I stopped and looked at it, as if the storm didn't exist. The storm that would be on me soon. Was on me.

Beyond Green Mountain I broke through the trees and my pace quickened in an attempt, and a silly one at that, to get off the ridge before the storm got bad. I was in the alpine and there were only a few islands of safety between here and the Obstruction Point trailhead. I had two mountains to clear before then, both nearing 6500 feet. It was beautiful.

The place was fantastic. In good weather, I would have lingered in that way that only long distance hikers, that is, people who measure hikers in hundreds of miles, can do. There is an ability that people who walk for long periods of time in the woods, forests, mountains, deserts, prairies, and swamps of our country, and even our world, there is this ability, you see, to spend time well.

I would have lingered, but I couldn't. The storm was on top of me and the wind had picked up. A light drizzle was falling, but nothing too serious so far. I made the decision to not put my rain skirt on and just pushed forward. There was no good reason for this and there were plenty of good, rational ones to stop, take it out of the mesh pocket of my pack, and put it on. Instead I hiked on, quickly.

I was climbing Maiden Peak when I rounded a corner and the brunt of the storm hit me in full. I could hear it, in fact, before I got to it. I could hear the howling, blowing winds and knew something bad was waiting for me around the corner. I screwed up my courage and looked out at the stunning land, then plowed around the corner and into the full force of the raging storm.

The wind hit me first and I realized that what I thought was light drizzle was really rain driven far in advance of the storm by the powerful gale. Last year when Kevin, Wayne, and I climbed Mount Rainier we summitted in sustained 60 mile per hour winds, as recorded by the NPS weather station. It was not pleasant. While the winds that battered me were not up to quite the same standard, they were in the 40-45 mile per hour range, which is more than enough to send skinny little girls sailing off to Kansas.

The wind was driving the rain hard enough that it stung my face through my month and a half old beard. It was hard enough, in fact, that the left side of my pants were getting wet: The right side was still dry. The temperature dropped into the 40s and my hands, unprotected by gloves and on the grips of my poles, began to go numb. I was nearing Maiden, though, and wasn't especially worried yet about my health. As long as I could continue to move and generate body heat, as long as I was still mobile, there was no danger from hypothermia, and that was the only real danger.

I thumped over Maiden and dropped down the other side, trying to spy in the distance Obstruction Point. The place got its name, incidentally, from back in the day when the NPS tried to build a road that connected Hurricane Ridge with Deer Park. Everything was going fine until they got to a place where they just could build around or over due to the rock. And so they called it Obstruction Point. I pushed my pace as I felt my body actually start to chill, and that gave me some worries. The wind was strong and served to rob my body of any heat it was accumulating. Even with a wind proof jacket on and fairly stout pants, it was strong enough. I started to worry.

Faster. I furiously climbed the trail up to the bald, open summit of Elk Mountain, where an alpine paradise surely was to be found. I could see only thirty feet around me, but mostly I looked at my feet to keep rain from being blown onto my face and down into my jacket, which was getting waterlogged from the beating it was taking. It was an old jacket that has seen many days and I should probably have replaced it, but I'm loathe to buy new things and its got sentimental value to me anyways. I pushed hard across the flat top, taking long, four foot strides and moving at, maybe, four miles an hour. I was cold and I was wet and I was worried about hypothermia. It was still another, eightish miles along the Obstruction Point road to get to Hurricane Ridge where there was a visitors center. After yesterday's diatribe on the parks, cars, and the front country touron attractions, my hypocrisy seemed self evident. I scampered down and passed a side trail heading south to the Grand Valley, which I remembered Strickland as saying held sanctuary for storm battered hikers. Why anyone would go down there instead of hiking another mile to the trailhead was beyond me. I pushed on and soon came to a gravel parking lot with lots of cars and no people. But there was a bathroom. I hopped inside and breathed with relief, safe from the wind and the rain, at least for the moment.

I stood in the bathroom and felt the warmth that came from going from a very cold place to one that is only moderately cold. I knew the feeling wouldn't last and quickly got my thermal top out of my pack and put my hat on. I ate a candy bar and began to shiver a bit. I'd have to leave the outhouse eventually, but once I started moving I wouldn't stop until I reached Hurricane Ridge: I needed to move to keep my body at a reasonable temperature. I was wet and cold, but I needed to move to survive. I relaxed in the outhouse for twenty minutes, then packed up and headed outside to race the eight miles to Hurricane Ridge.

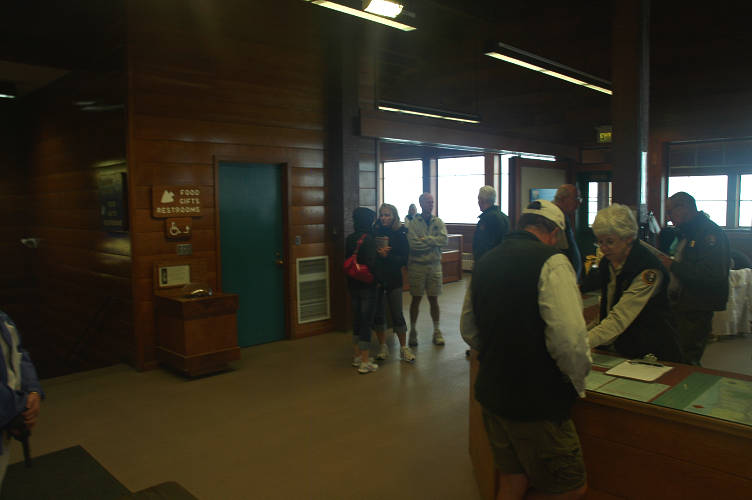

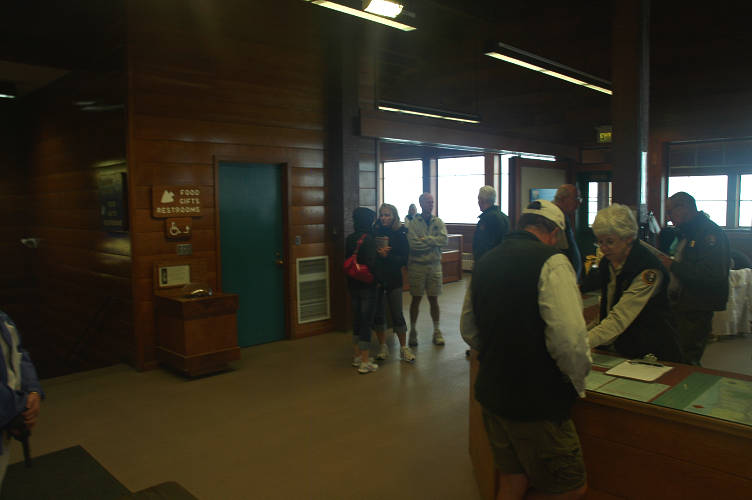

When I emerged there was a family of four loading up an SUV after finishing their backpacking trip. Why not? I wandered over and asked for a lift to the visitors center. Sure, hop in. The family, consisting of husband, wife, and two small boys, lived down in Port Angeles and had had a difficult time on their overnighter to the Badger Valley. But they were all smiling and happy as well, perhaps basking in the warmth of the vehicle and knowledge that there suffering was over. Nice people. They dropped me at the visitors center after I declined a ride down to PA, as its called locally. The weather might clear up, I reasoned, and if it didn't it should be an easy hitch to town. I thanked them again and went inside the visitors center, which was filled with retirees and young children, presumably the grandkids.

I put my pack and poles in a corner out of the way and went downstairs where there was a small cafeteria. I'd been to the visitors center many times before and knew my way around. I got half a cup of hot coffee from the young girl behind the counter and she started a fresh pot for me. I was shivering in the unheated VC, still soaked from the storm and the ridgeline traverse. I milled about and got some more coffee from the friendly girl, then headed upstairs to find out what I could about the storm and the weather. A friendly retired man stopped me on the way up the stairs and asked what I was doing, for I was clearly the only hiker in the building, rangers (retired volunteers, actually) included. We talked for nearly 30 minutes. Bill and his wife were from Colorado and were trying to visit all of the national parks as part of their retirement. They had flown out a few days ago and, after seeing the sights in Seattle and the Islands, had rented a vehicle and come up to PA and the park. Bill was interested in long distance hiking, but didn't quite know if his body could handle it, or even where to really get started. After all, a 2000 mile hike seems really daunting before you start it!

Bill offered me a lift down the hill if I needed it, for which I thanked him: How many people would offer a stranger a ride? I tracked down the rangers to find out about the weather and whether or not it was an extended one. They didn't seem to know, though there was a posting about the forecast for the day and one about tomorrow. Both were for rain. But beyond that they didn't know. I wasn't expecting much more. But then one of the volunteers decided to find out. He told me hang out while he called around. No problem, I thought, as I looked out into the swirling grey storm. I've got the time. Ten minutes later he came back: He had called around until he reached someone with a long term forecast. Bad news, he said. Nasty today. Nasty tomorrow. Nasty the day after that. Maybe only disgusting after that.

I was going to be traversing to the windward side of the Olympics and crossing several high passes. The Olympics get the full brunt of any storm moving in from the Pacific, and this looked like a big one. The rain would be wind driven and constant and the sun would not come out for several days. The decision to bail to PA was not a hard one to make. I tracked down Bill and met his wife, Ginger, and took them up on their offer. I was happy to get into the car and feel warm once again. I was wet, many of my clothes were wet, and there was little prospect for the future. I could do another day. Maybe one more. But at some point I'd need to be able to get dry. The Coloradans took me down the hill and into town, where the storm wasn't so bad. Although they had been paying $220 a night to stay at a Red Lion, they found me a room at the Riviera Motel for $71 a night. Far more than I would normally pay, but pretty cheap by summer PA rates: The owners have to make most of their living between June and September. I thanked Bill and Ginger again and retired to my room.

Well, for the moment any ways. I dropped my pack and set out to look for food: I was starving, having eaten only the candy bar in the outhouse since leaving Deer Park. I found an All You Can Eat Chinese place close by and went to work. I ate three plate-fulls of fairly respectable buffet chow before calling it quits. I could have pushed in another three, but I also wanted to eat some dinner and ice cream. I was looking pretty rough when I paid with my credit card and I suspected that the woman behind the counter thought I might have stolen it. I showed her my drivers license also. On the way back I bought some Hurricane Ice and a 24 oz. can of a grape flavored, 10\% alcohol energy drink called Four Max. I needed something to drink in the shower, after all.

I spent the rest of the day watching the weather on TV, lounging in a towel on the bed, and drinking the two cans, which cost me $2.40 combined. I wasn't sure what I was going to do. Perhaps hitch into the Elwha and continue? No, that would put me in high country and my now dry clothes would just wet out again; I wouldn't have any place to run to. Over dinner at a local Mexican joint I decided that I would go to Forks instead and just skip over the Olympic mountains. I didn't want to do it, but these are my home mountains and I can come back anytime. Indeed, I'd already hiked much of the route I was planning on taking. This would also give the storm some time to settle down and for the rain to go away. I didn't think it would, but there was better chance in three days time than in two.

I floated back to the motel, picking up beer and ice cream on the way back, and noticed that, for the first time on the trip, I was generating some attention from law enforcement. Not much, but as the police drove by I got some long looks, as if they were trying to burn my image into their heads incase they needed to come looking for me. I didn't take it personally. I looked the part. They didn't get out of their rollers to come and interview me and ask for ID, or put me up against a wall and search me. The Border Patrol did that. I sat in the motel room a little glum, and not all of the sadness, or really depression, could be traced to the strong beer I was drinking. My trip was coming to and end, and not in the way that I had pictured it. I was jumping past the last obstacle to get to the ocean and then go home. On the other hand, it was consistent: I was making stuff up as I went, sometimes not for the best. But I had the time and freedom and inclination to do so. And that, I thought, was what the summer had been all about.

The weather was frustrating. Standing on the balcony of the Riviera, I could look to Hurricane Ridge, or rather where it should be, and see only a storm. But to the east and north it was pleasant. Sunny, even. I wandered down to the Olympic Bagel and ate some breakfast while reading the newspaper, a bit unsure about what to do. I didn't really like the idea of taking the bus to Forks anymore, but neither did I want to go up and over Appleton Pass and High Divide in a storm. I've been over both before and neither are places you want to linger in a storm.

The sun was actually shining on Forks when I checked out of the motel after watching the Weather Channel for an hour. The weather just wasn't going to get any better up high and there was a slight chance it might improve over the next few days. I might have a chance on the coast, but definitely didn't have one in the mountains. The next bus to Forks wasn't for a few hours, so I amused myself by wandering around PA seeing the sights.

PA isn't much of a town, but for the Olympic Peninsula it is a metropolis, complete with every possible luxury you could imagine. The Peninsula is admittedly pretty uncrowded, however. The main attraction, other than the park, is the ferry to Victoria. If I had any semblance of intelligence I would have brought my passport with me and simply taken the ferry to Victoria for a few days to hang out and wait for the storm to pass. PA has a lot of good places to sit in public, which makes it an oddity for the United States, where we try to push things like sitting on a bench into the private sector (i.e, coffeeshops).

I wandered around town for a few hours and ended up at the bus stop eating a pint of ice cream and drawing surprisingly few looks from the others. There were at least three other homeless people waiting to get on the bus and even the non-homeless looked to be a bit down on their luck, regardless of age. Once I got on the bus, though, I found myself the object of more attention than I normally like. One of the homeless people got on the bus with me, which cost $1.25 for the ride. I sat next to a group of three teens who were amusing, and also sad, with the stories they told of their lives. The sad thing was that they really seemed to be proud of their lives. The fact that one was on her own while her mother did time in jail, and thus had the trailer to herself, was a source of pride for her. She was proud that she was living, as she said, "a trailer life." I wondered what Jason might have said to her. He probably would have opened a beer.

It rained on and off during the ride to Forks, which was about as I remembered it. The bus dropped me at the transit center, which also held a ranger station for the park. I stopped in and got a permit and a bear canister to keep raccoons away. Normally I don't like to do this, but it was so convenient that I really couldn't avoid it. Plus, I wanted to get a tide chart and they gave them away for free there, as well as a weather update. After collecting the black canister, my permit, and my tide chart, I set out on foot to figure out where to spend the night. Although I had planned on hitching south to Bogachiel State park and camping, especially since I had to go that way anyways, I thought I'd ask about motels. Maybe someone would give me a break.

I stopped at nice looking place, but they wanted $80 for the night. I tried to Yogi a lower rate, but wasn't getting anywhere. Surprisingly, the woman behind the counter suggested the Town Motel. I remembered seeing an advertisement for the place on the way into town. It highlighted the fact that they had color TVs. Must be cheap. The rooms ended up being clear and comfortable and not too expensive. This was my last town stop on the PNT, so I might as well live it up. I walked back into the heart of town to the liquor store, where I picked up a 1.75 L of cheap whiskey for the last three days on the PNT. I made a stop at Pacific Pizza on the way back to the motel and found the greatest pizza I'd had outside of Chicago: The pesto-artichoke heart-sun dried tomato-roasted chicken pie was simply divine. I was well rested from my encounter with the storm and didn't need so many luxuries as I indulged in, but this really was the last stop of the trip. Eight hundred fifty miles of walking had come down to this. Just so that I wouldn't get too soft, I avoided the microbrews at the Safeway and got some good, cheap workingman's beer instead. My summer was almost over, but rather than finishing quietly on the coast, it looked like I was in for a brutal slog along the coast as the storm system that had thrashed me in the mountains was hanging around, unwilling to let me finish my walk in the warm sunshine. Things were just as they should be. The Japanese have a saying: No praise, no blame. Just so. That's goddamn right.

I didn't have a lot to do today. I just needed to get to the Oil City Trailhead on the coast, which I thought would involve a medium length hitch and then a 8 mile walk down a gravel road. I ate breakfast at the local joint, called the In Place. The taco omelet was forgettable, but the stunning 19 year old hostess reminded me someone I once knew, and that was pleasant. Food always tastes better when you're in a good mood. I hung around the motel for a little while, then walked out to US101 to try to get a ride. I was right across from a trailer park and hoped one of the residents might give me a lift. I stood there looking like an idiot for an hour, preposterous grin on my face, until finally an old Ford Explorer lumbered out of the RV park and waved me over. This was how I met Diego.

Diego was wearing a tan Stetson and a white wifebeater that showed off his heavily muscled arms. Within a minute or so it was clear that his immigration status was dubious. I didn't care. Living in Washington I have the luxury of being indifferent about the immigration debate in the country except when it concerns humanitarian issues. Diego picked me up because, as he said, he thought I was like him, without papers and that the Border Patrol had been active of late. The hat and the beard must have thrown him. Diego, which isn't his real name, by the way, had lived in the country for the last five years, though he had first come here in 1998. He went back to Mexico because he got lonely and wanted to be with people he knew and in a culture that he understood. He had lived throughout the Central Valley of California, but had moved up to northern Washington because there was less pressure from the federal government and people were more relaxed. He left good paying jobs in construction and home painting to come northward in order to escape some of that pressure, even though few people here spoke English.

Diego used to work for timber companies, or rather the subcontractors that are paid to hire temporary workers, and earned a reasonable living planting trees. This is hard, back breaking work that frequently happens in the winter and spring, when the temperatures are low and it rains constantly. Tree planters are wet, cold, and miserable for several months a year, but the wages are normally good enough that you only have to work for four or six months a year. Several long distance hikers I know do this for a living. Combined with jobs at ski resorts they finance their lifestyles. But with the downturn in the economy the subcontractors were paying undocumented workers like Diego terrible wages. I don't mean minimum wage. I mean $15 to $20 per day, vastly below the minimum wage. He had switched to collecting mushrooms for sale to fancy restaurants in Seattle and Victoria, but the price had dropped from $6 per pound to $3 and he couldn't make a living on that, no matter how many hours he worked. He just wanted to go back to Mexico now, but he had a life here. A vehicle, a place to live, friends. Packing up and leaving would be difficult.

When I mentioned the boom times in Republic due to mining he became very interested, though I couldn't tell him what he was most interested in: "Do they hire people like me?". If he couldn't go back to Mexico he wanted to bring his sister and wife up here to live with him, but said that the border crossing was very difficult for women, Not because of the desert, mind you. Rather, the coyotes, as the border guides are known, can be cruel to women, especially young and attractive ones. Diego shook his head and was quiet for a little while. I told him about my trip, but left out key details, like the fact that I had a doctorate in mathematics, a comfortable apartment at home, a new car, plenty of food to eat and wine to drink, had more than the clothes on my back, and had the entire social system of the United States at my disposal. I was embarrassed at how wealthy I was and at how many privileges I had. I didn't want to tell Diego because I didn't want him to ask the question. Why was I doing this instead of working? Instead of spending time with family? Was this really the most important thing in my life.

Diego dropped me off part of the way down the road to Oil City. I thanked him and watched him drive off. I had met so many interesting people this summer, people I never would have met had I not left the confines of settled life and embraced the unstructured life that I had been living for the last forty six days. I looked back at the mountains and was glad that I was down in the lowlands: The storm was still raging up high.

But for now it was only cloudy where I was and I had a pleasant stroll in front of me through the lush, verdant forests that ring the park. The forests are under the care and supervision of various private timber corporations, either owned or leased from the appropriate federal, state, and tribal governments. The timber companies are known to care for the land to the highest degree possible and maintain strict standards in regards to sustainability, conservation, and environmental protection. They do this out of a sense of justice, honor, and a look toward the future, for we certainly do not have any such reasonable standards in place.

Although I had heard horror stories about clear cuts and land slides wiping out farms and tribal buildings, I was pleased to see that the companies were being responsible with the land. They were employing ten people, twenty maybe, with good quality, high wage jobs, except when they were hiring people like Diego for starvation wages. But it wasn't just the timber companies commitment to bettering society, it was their stewardship of the environment that was so heart warming. I stopped by one especially large slag heap and fished the bottle of whiskey out. I needed a drink.

I was pretty happy when I ended my walk through the logging lands and came to a few farms and some barking dogs. The dogs, though, just raced out to see who was coming and I made friends with them easily. The two legged owners were working on a tractor as I went by, but had time to smile and wave at me. I soon came to the Hoh River, whose valley I had actually been following for a while. The Hoh is one of the major rivers that comes off of the western (windward) side of the Olympics, some of the others having such neat names as the Sol Duc, Quinault, Queets, and Quillayute. These are major, non-fordable rivers and they drain the rainiest area in the contiguous United States. The Hoh, here, was slow, placid, and braided. I could have easily swum across the particular braid in front of me.

The Oil City trailhead was not much further along. There were a few cars parked and an industrial grade outhouse, but no place to camp. This wasn't entirely unexpected, but I had hoped there might be a flat bit of ground away from the parking lot. I gathered water at a small side stream that was running hard from the storm and set up my campsite for the night. It began to rain, which made my decision all the easier. The porch of the outhouse would be dry, and I could prop the door open and put my legs in that area. It wasn't the worst shitter I've slept in, but it was a long way from the best. And yes, I've done this on multiple occasions.

The rain fell softly through the late afternoon and early evening. I drank tea and read and wrote in my journal, and then made dinner and drank whiskey and wrote in my journal. I glanced at the tide charts but mostly as a formal issue: I was supposed to look at them, so I did. I was sure that something would work out for tomorrow and that there would be plenty of room to hike along. It was quiet at the trailhead, just me and the rain, which continued into the night when the sky was black and I was quite tipsy from the cheap whiskey. I should have been reading the tide chart in combination with the guidebook, but I had hiked too far this summer to worry about details like head lands and high tides, which wasn't until nearly 11 tomorrow morning. 13 mile day, easy. I went to sleep listening to the rain fall around me, comfortable in my dry place. There is no more soothing sound to someone who lives outofdoors than the sound of rain hitting a roof over your head. I only had a few more days on the PNT, but I knew that that sound would stay with me when I returned to settled life, and that was comforting.

It rained without end. Soft at times, hard patter at others. I had intended to sleep in, but three vehicles rolled up around 7 am and roused me. They were not here to hike, but were just shuttling vehicles around so that some hikers coming in wouldn't have to try to hitch out of the trailhead, or walk as I had. I must have looked fairly pathetic, because one of the old men poured me a half liter of coffee with a wink and smile. "Looks like you could use it." The left quickly and I was alone with the coffee, which I drank out of my pot, having no other container. The air was a solid bank of mist, solid rain, and gave the land an interesting, uniquely Olympic feel to it.

I finished my coffee and put water on for tea, having no need to rush. High tide was 11. Plenty of time. I was part of the way through a pot of tea when a band of hikers came out of the woods, muddy and bedraggled, soaked to the bone and looking very, very thankful to be alive. I got a bit nervous. I wandered over to find out their story. Engineers from Indiana visiting friends in Seattle, wet and rainy all the time, lots of mud, near death on the coast, slippery rocks, mist, wait, near death? Really? Where? They told me the story and I tossed my cooling tea out of the pot to pack up. I didn't have a lot of time. Suddenly after a summer of not having any deadlines to make, I had a very major one. If I had thought through it, I would have spent the day camped out under the shitter and tried again tomorrow. But thinking takes time, and I was convinced I didn't have a lot of it left.

The group had set out at 4:30 this morning to take advantage of the lowest possible tide in order to get around Diamond Rock. According to their story the ocean was coming it as the rounded it at 6 am. A quick glance at the tide chart showed that the tide wouldn't get any lower than it was right now until tomorrow morning. I was going now, or tomorrow. I packed quickly and sped down the muddy trail. The footing wasn't terribly bad, especially as I had trekking poles to help me along. I came out of the woods and the trail dropped onto a cairned route along the flood plain of the Hoh. Massive logs were everywhere, stretching out to Pacific. I stopped and paused for a moment in the misty rain. This was my first sighting of open water, of the Far East. I didn't pause for long before setting out as quickly as I could.

The route was only approximate and in good, dry conditions I would have enjoyed it very much. But hopping over logs, tightroping trees, and generally trying not break an ankle, while under a time constraint and with rain overhead, I wasn't in the best of moods. And then things got worse. I shimmied over a massive cedar and dropped down the other side onto the logs below and went straight into the ocean up to my thighs. I climbed back up onto the cedar and tightroped it to another log, which I walked to another log. I lowered myself gently onto another flotilla of logs which dropped only a bit into the water. Even with an air temperature in the mid 50s, I was sweating hard from the work and the water felt refreshing. As long as I could keep moving, hypothermia wouldn't be a problem. It took me nearly forty minutes to negotiate the logs and make it to the start of the rocky route around Diamond Rock.

The rocks were slippery, but as long as I was careful and used my poles the small ones were not a problem. It was the larger rocks that slowed me down, for I had to actually climb and pay attention to what I was doing. I couldn't use friction for my feet, for everything was a slimy mess and a fall from ten feet up would have very, very serious consequences for my health. The ocean was close and moving in. At times I got to within a few feet of it to cross a little spit of land. At other times the waves lapped up against my shoes. I had been moving well for forty minutes when the ocean came in and a large boulder blocked my way. Not wanting to tangle with the ocean, I scaled the boulder and stood twenty feet above the ocean. I was almost there. I could see the safety of Jefferson Cove just around the corner. All I had to do was get off the boulder, cross a small sandy beach, traverse on last section of rocks. With the ocean coming in fast, there wasn't a lot of time: If the last section of rocks went under water, I was stuck for the next six hours. With the rain and wind, hypothermia would be a very real danger.

From the top of the boulder I had two options. One was a friction slab route down off the boulder directly to the sandy beach. But I after some scrambling and testing it, I decided that the risk of a slip on the wet rock was just too much. I went to the ocean side of the boulder and found that someone had anchored a rope to a log wedged between the boulder and another. The problem was that the rope led down to the ocean. The tide had come in enough that the rope ended in water. The water didn't look deep, but the ocean waves came in every ten or fifteen seconds or so, and I wasn't sure if I could batman down the rope and get to safety in time. I looked at the godforsaken top of the boulder, looked at my watch, and grabbed the rope.

The rope was knotted, but the descent down was fairly athletic with a lot of stemming needed to keep from swinging out and hitting other boulders. The rain fell, as always, and the waves were coming in hard. I got myself into a position above the water, with my feet on small ledges and hands on the rope ad waited for the next wave to come in. Come it did. The wave hit the rock, rose up, and hit me hard. It pushed me completely into the wall, nose first, and rose up over my head, splashing down over my entire body. I was soaked to the bone by it. I held on tight to the rope as I felt the wave leave, trying to suck me out along with the sand and water. "This is not a good idea," I thought. I turned my head to the Pacific and saw another wave coming, smaller than the first. It hit hard as well, but my grip held. Salt water dripped from my beard. The next wave was still ten seconds away, so I dropped into the nearly knee deep water and started a frantic scramble to the safety of the beach. If the next wave caught me here, it would take me out to the Pacific to visit the Sirens. I couldn't see where my feet were for the ocean was churning white and brown. My foot caught on an unseen rock and my body levered over it, with the shin of my stuck foot acting as the fulcrum. Mercifully my foot became unstuck just before my leg broke and I splashed into the water face first. Fortunately I didn't hit a rock. I pushed up out of the water, in a frenzy, for I didn't know where wave was. I moved hard and lept out of the water and onto a rock, just as the wave hit. It sprayed me, but I was on the move again and made the beach with only a few bounds.

I stumbled over onto the cove and felt my leg burning. I didn't want to look at it until I was around the rocks and onto the safe sands of Jefferson Cove. I limped along, rounded the point, and wandered over to some logs, as far from the Pacific as I could get. I sat, clothes completely soaked and dripped wet from my beard, face, hands, everything, and had a look. My legs was clearly not broken, though the force on it was enough that I could feel large bumps that had formed directly on the shin bone itself. That couldn't be good. The skin was scratched and bleeding, but the cuts were not deep enough to worry very much. There was a fair amount of blood, though. My hands were bleeding as well, from the cuticles, the knuckles, the palms. I had ripped away much of the skin from one of my finger tips. My nose hurt. And then I remembered my camera, which had been riding in a very non-waterproof bag on my hipbelt. I took it out and sighed. I could see water in the lens. I was sure water, salt water, was in the body. Electronics generally don't function well when immersed in salt water. I pointed the camera and pressed the button. It went click. A photo! By some miracle the camera was still working and I quickly snapped a photo of myself after the near death experience in the Pacific. I put it away just as quickly, though I didn't see how the rain could possibly make it any wetter.

Looking across Jefferson Cove I was a little unclear where the trail went. I wandered in the northerly direction, giving the Pacific a wide berth. At the far end I had to walk across some enormous logs to avoid the water and gain a chunk of muddy land the ended at a large, mossy cliff. I looked around and couldn't see a trail over the headland. There was water in front of me, leading around a boulder, but I didn't want to check it out until i made sure the trail wasn't behind me. Fifteen minutes of searching convinced me to move on and brave the water again.

I crept around the boulder, taking care to avoid the waves as best I could and squished my way through the slimy clay that was running off of the hillside. After ducking around a few more massive boulders I found the trail: A sequence of boards somehow attached to the side of the muddy cliff, with a metallic rope hand line attached to a tree above. Definitely not Pasayten hiking. I scrambled up into the dense forest above and got out of the rain for the first time in a few hours.

The storm was churning the Pacific toward the south, with dark, nasty clouds everywhere. Yet to the north there were a few patches of blue, and that gave me some hope.

After the initial slippery scramble through the mud I reached the top of the headland and only had to skate through on flat mud. But mud nonetheless. The interior of the forest was beautiful, with lush, green vegetation everywhere that screamed rainforest. There was no doubt about the kind of ecosystem that I was in. I was also soaked to the bone and my camera water logged, but at least I was around Diamond Rock and hopefully the last of the dangerous areas.

I skirted along the edges of the muddy trail, then realized that I couldn't get any wetter or muddier than I already was. From then on I simply tromped through the mud. The forest gave way to views of the Pacific, which in the direction I was heading looked like it might spare me for a while.

The trail dropped me down through the woods and I heard the roar. Whenever you hear a roar in the backcountry something bad is about to happen. Like getting eaten by a bear. Or crushed by a rockslide. Or drowned by a river. In my case, it looked like the river thing. I knew from the map that I would have to ford Mosquito Creek, but the guidebook mentioned nothing about a ford. The shelter and outhouse in the guidebook didn't seem to exist any longer, or at least I couldn't find them. All I could see was the raging river, swollen by the rains from the last few days, and the incoming tide that was pushing furiously against the river. Perhaps this was an easy ford when storms had not pounded the mountains, or when the tide was out. But now I was looking at something that looked distinctly deadly. I put my camera into my pack, strapped my poles on, and found a large piece of driftwood to use as a brace. I waded in.

I moved slowly out into the river, slowly shuffling my feet and making sure to keep my balance. I didn't want to get swept down to the where the tide met the river: It would just Maytag me around until I drowned. Knee deep. Thigh deep. Waist deep. Turn around. I found a different spot and tried again. Ankles, calves, knees, thighs, waist. Turn around. I looked up river to where the river was trapped in a sort of pond and scouted around for something better. A tree was mostly underwater, leading from the other side to about the midpoint of the ford. If I could reach that, maybe I could use it as a handline. Above it was impossibly deep, so I approached it from the downriver side, working slowly toward it on an underground ridge that I hoped wouldn't end abruptly. I made the former root end of the tree and started along it toward the far bank, using it for my hands. I had only made a few steps in the positive direction when the ridge gave out and I was quickly into the water up to my ribcage. Back I went.

I tried one place and then another. I pondered just swimming the lake section, as it was quite slow, but deep. I dismissed this as I didn't want my sleeping bag to be completely wet: I'd need it later on. I had nothing left to try: The water was too violent near the tideline, yet this was the only place shallow enough for me to possible ford. It was slow, but too deep farther up. I thought about turning around, or waiting for the tide to go out (in about four hours). I decided to try the log one more time. I retraced my steps along the underwater ridge to the root end, being as careful as before. I grabbed the stoutest roots I could find and hauled myself out of the water and straddled the former root ball. The body of the tree was underwater, but its 18 inch width should be good enough for a tightrope. Out of the water and dry, this would not be a problem. But the tightrope was underwater and that water was flowing. I probed below the tree with the driftwood and found that it was about six or seven feet down to the bottom. Carefully I shuffled out onto the trunk and began the tightrope. Moving slowly and in control, I made progress across the log. After a few feet I realized the danger was past: With each step I got to shallower water. A minute later I hopped off the log and onto the other bank. I really hoped there wouldn't be anything else like this. Looking back toward Diamond Rock, I realized it had taken me a lot of time for only a few miles of forward progress.

It was raining on me once again, the blue skies having vanished on me. But I was safe and there was only one more major looking ford on the route and it was mentioned in the guidebook. I didn't know if that was a good or a bad sign, but for now all I had to do was walk on the beach in the rain and try to stay warm. It was really rather pleasant after the near-death along Diamond Head, the sloppy forest, and the harrowing ford of Mosquito Creek.

Off shore loomed Alexander Island, looking just like a mesa or butte might down in Abbey Country. I thought it would be pretty fun to go out there, but like a lot of federally protected land in the park system, no fun was allowed: Access was not allowed to the public. Of course, I really doubted there was much patrolling going on.

The coast was beautiful, especially as I now had easy, pleasant walking. I was wet and a bit cold, and I had nowhere to get warm or dry, but at least it was scenic and the fog and mist gave the land and ocean a sort of interesting atmosphere. Back in 2004 an acquaintance of mine and his girlfriend walked the Pacific coastline from Neah Bay, about thirty miles north of me, to the Mexican border in the south. While you can't walk the exact coast line, they stayed pretty close, only going inland when topography or landrights forced them to.

Tha Wookie and Island Mama were the first known people to walk the length in one shot. They had gotten a lot of their information a few people who had walked the length in several sections and they were sure others had done similar things but not publicized them. The attraction of such a hike was obvious. The land was gorgeous, the environment completely unique, and the flora and fauna much different from a normal mountain or forest trail. I had thought quite a bit on the PNT about doing something similar next summer, but now I was not so sure.

My beach route eventually gave out and I was forced into the forest to climb over an impassable headland. The view from up high were particularly nice, even if the storm did not look like it was going away. It looked like it was getting ready for round two. I wasn't sure I wanted to do something like the coastal hike after my experience with Diamond Head and Mosquito Creek. Although I was sure that the further south I went the gentler the land would be, I had to get across several very large rivers in Washington and deal with the logistical problems of crossing the Hoh and Quinault Reservations: That wasn't my land and I would need to get permission to cross it, permission that wasn't likely to be given for something as silly as a walk on the beach.

And then there were the problems in the south. While it might be relatively fun to hike around the San Francisco area, I would not want to linger much in the Los Angeles area, or in the Port of Longbeach area. That just didn't sound like a lot of fun. From an overlook I spied two deer walking casually along the beach. Normally I don't get terribly excited over deer. But for some reason seeing them walking along the water front, far from where I normally saw them, was interesting. I watched them wander to the far side, then began my descent toward them and Goodman Creek.

I dropped down and forded a gentle, though deep, creek, and then forded a fast and shallow one, before coming to the main event. I didn't hear a roar. I found myself at edge of the creek looking at two hikers, one nearly to me and the other on the far side. I put my camera in the pack and strapped the poles on, taking comfort from the fact that the other hiker had made it safely. He thought it was pretty easy and so I waded in. The ford never got worse than just below my waist, but it was very slow and the ford easy. I coaxed the other hiker in and helped him for a bit, then left to cross to the other side. Though soaking wet, I was past the last major problem that I could see on the map, at least for today.

The creek ran between hills and I had to climb through the mud up and over another headland, then pass through the forest, before I could descend to where I spotted the deer earlier. The view from up high was, again, stunning, yet also scary: The storm was still here and could open up on me at any time.

I had some rain gear with me, but nothing stout enough to really keep the wetness and the cold at bay. I could do this for a day, maybe a bit more, but then I would need to be able to dry out. There were many shelters marked on the guidebook, but the park was in the process of removing all of them and had started, I believe, with the coastal sections. The descent to the beach was via a rickety, steep ladder with a rope to hold onto for your hands. While not difficult, the athleticism required for coastal hiking was vastly greater than that required inland.

I'm not sure why, but the sight of open water stretching to a land far away is always some how calming, yet paradoxically also exciting. It isn't simply a feeling of serenity or of interest. It is more than being centered or ecstatic. To say that the sight brings me a feeling of hope is to invite misunderstanding. People use the word hope in too vulgar a sense. "I hope she'll go out with me." Or, how about "I hope tomorrow will be sunny!" How many times have you heard, "I hope I get a raise." People use the word "hope" where they really mean "want".

This is not what I mean when I say that the sight gives me hope. I suppose it is some deep rooted drive in some portion of the human race that needs there to be an "over there" even if they will never get to it. The hope, or rather the feeling I get, is more along these lines. I have hope for the future because I know the world is large and my life is short. I will not exhaust it even if I live to be 300. The sea is the ultimate separator, and the Pacific is what lies between American and Asia, between the New World and the Next World. It was Christopher Columbus who said, " Following the sun, we left the old world." The sun goes West, not East. We leave the old for the new.

And so as I walked along the coast line I found my eyes drawn to the water, not to look at the storm but rather to look to the Future. Not to Asia so much as to the immediate future, the next few months, the next year, the next decade. Tomorrow. The world was large, not small as people with small minds seem to think these days. The ability to talk to someone in Nigeria on a cell phone or look at a satellite image hasn't shrunk the world, it has only insulated us from it: The computer screen allows to think we've been someplace, or understand something, when we really haven't faintest clue about it. The communications revolution has not served to better our way of life in any significant way. No, it has only helped businesses sell us more things we don't need. And to sell Guatemalans things they don't need, like Coca-Cola and Brittany Spears. Is it really important that people be able to contact you at every moment of every day? Is your input really that necessary for the smooth functioning of society? I bet if you turn your phone or Crackberry off the world won't end. Where was I going with this? I seem to have lost the thread of my thought, which is easy to do when you are in a special place like the Olympic Coast.

Right, the world is still large. The fact that it is a large place is self evident when you find yourself on the Olympic Coast where there is no cell phone reception, no roof over your head, no Google, no email, and you have no greater responsibility to stay alive and to try to enjoy yourself. Try to tell Tha Wookie or Island Mama that the world is a small place: They made the world even larger than it already is. I can hear people yelling at their computer screens right now. "Well," they say, "I live in New York City and have hundreds of cultures around me. I can get on a plane and be anywhere in the world within a day. I can go to the Forbidden City, Lhasa, with easy. I can talk to people in Antarctica. I can hire someone to take me on a dog sled to the North Pole. Heck, I could get the French to fly me to the top of Mount Everest in a helicopter. You're large world theory is just a lot of wishy-washy, sentimental pap thought up by someone who wishes they were born five hundred years ago." Ouch, that really hurts!

All these things are true, except for the birth part. I like living with conveniences, like penicillin, durable shoes, and clean water. The ability to fly from New York City to, say, Capetown, does not make the world small. It makes your perception of it small. If you view the difference between Los Angeles and Ulaan Bataar simply in terns of the number of hours it takes you to get there, you have missed everything and you might as well stay home and watch a television show about the Mongols. Besides the United States is not Los Angeles and Mongolia is not Ulaan Bataar. I've lived all my life in the United States and have traveled extensively throughout it. Yet, I still have lots to explore. I haven't touched the Rio Grande border lands along Texas and Chihuahua. I don't know anything about the extreme north of New England and the Maritime Provinces. The Great Plains of Western Nebraska up to North Dakota have always interested me ever since I read Willa Cather. It isn't the world that has gotten small. It is that people's minds have shrunk and we seem to have no appetite for exploration, neither of ourselves, our culture, nor out land.

One of the things that I learned while walking from the Rockies was that in each and every town, hamlet, village, any place where people gather, there are stories and things of interest. Some of these ways and views are dying out as one generation passes into history without another that has learned its ways. Some of the culture might get preserved through isolated individuals who know the stories and the lore, who at some point had some one, some other human being, tell them, show them, learn them. They didn't get it from a computer screen. They got it from Us.

The author of the guidebook, Ron Strickland, that I had been using this summer has written two collections of oral histories from the Pacific Northwest. His guidebook could disappear and life wouldn't be any poorer. But his oral histories are very important and I suspect that he came up with the PNT as a way of attracting more people to one of the corners of America where traditions and culture are being lost. The last generation to have grown up on a frontier is passing away into the folds of history and we risk relegating them to a dusty library shelf to be classified by egghead scholars who couldn't tell a diamond hitch from a clove hitch.

Once culture dies, it is gone and it does not come back, at least in any authentic form. When Metaline Falls, Metaline, and Ione disappear and cease to be functioning cities, we will have effectively been cut off from our past. When the United States Army, and citizens, exterminated, or tried to exterminate, the plains Indians, such as the Blackfoot, Nez Perce, Shoshone, Sioux, and Mandan, we lost a part of authentic history. All we have now are a few reservations with tribal casinos and some books sitting on a shelf.

This, it seems, is the way of things. Our frontier culture is slowly dying from the urban cancer that metastasized in Europe a few hundred years ago and spread to our continent more recently. If we want to know something about the small towns in between the concrete jungles that will come to dominate the land, we must do so now. Now is the time to go and spend time in Forks. Or Bonners Ferry. Or Northport. Now is the time to learn about the city where you happen to live. Now is the time to learn about your family history. Now is the time to find out where you came from and how your genetic past is influencing your physical present. The time is now. It always has been.

I was sitting on a log in the sunshine watching the ocean, drinking tea from my cook pot. A water logged Cosmo was at the little clearing of a campsite at Scott Creek where I pitched my tarp. I had read through the magazine while having an afternoon cocktail of whiskey, straight. At first it was nice to ogle the women in skimpy clothes, but then a feeling of physical revulsion swept over me and I tossed it aside. The magazine represented the worst of modern culture. If I had been Che Guevara and we had a revolution, the editors would be the first people I put up against a wall. And so I found myself on the log staring out to the ocean, restful and contented, at least for the moment. My radio had picked up a station in Victoria and the storm was supposed to stick around for another few days. This bit of sunshine was just a short respite from the rain and cold. I had covered a lot of distance and crossed a large part of land. My walk would be ending soon and I would go home and have to try to summarize what I had done for others. I would have to put the summer into sound bites that people could absorb and understand and be happy with. But how could I even try to tell someone anything about Diego? No one would possibly understand what my interaction with Jason was like. Lee would be just some old broad in a run down town. In the end I would tell people that I walked from the Rockies to the Pacific. Yes, it was pretty. Yes, I was glad to be home. Yes, I took a lot of pictures. But could I ever actually communicate the experience in a meaningful, authentic way? No, not to everyone.

This isn't good, I thought to myself. It was completely black out. No moon, no stars. Nothing. It was the sound that was spooking me. The whooshing of the wind against my tarp was loud enough to wake me up. I would have woken anyway, as there was rain spray on my face. The storm was back with a vengeance and my campsite had just enough of a view to let the high wind drive some of the rain inside the front entrance of my tarp. I should get up and lower the front. That would do it. Instead I just curled further back in the tarp, pulling my ground cloth with me. I slept, curled into a ball, quite comfortably until the morning broke.