Chiang Mai

December 17, 2006

My god, I thought upon awaking, I haven't slept this good in a bed in a long time. The bed in the Sumit hotel was so solid, so firm, that it was almost like sleeping on a board, but one with enough give to contour, slightly to the body. The only bed that could rival it was at the Al Harramein in Damascus. The only bed that could beat that one was a nice pice of pine duff. I scored some pineapple in a local market around the corner from the Sumit and was amazed by the density of tourism in Chiang Mai. I had stayed in Chinatown when in Bangkok, well outside the backpacker ghetto of Khao San Road, and Phitsanulok isn't on the over-night tourist route, and thus had avoided much of the tourist scene during my brief time in Thailand. Signs in English, cooking classes roaming the market for supplies, travel agencies everywhere advertising cheap buses to Bangkok, Laos, Nan, Burma, and a myriad of destinations, internet cafes, Italian restaurants, wine bars, and so on and so forth. Curiously enough, I didn't seem to mind it.

The pineapple, while very tasty, wasn't quite enough, which prompted me to stop in at a cafe for a bowl of Khao Tum khai, which was nothing more than chicken-rice soup. Doused with some chilis-in-fish sauce, it made for an excellent breakfast despite of, or perhaps because of, its simplicity. I bought a bag of rambuttans and a dragon fruit on the walk back to the hotel, grabbed my gear, and set out to walk around Chiang Mai, with the vague destination of Wat Phra Singh in my mind.

Given the amount of farang in town, I expected the wats along the way to be jammed with people like me. However, at each wat that I stopped at along the way, I was usually the only paleface around.

Some of the wats were indicated on the map in my guidebook, some were not. All had some little bit of charm to them, some bit that held my attention for a while, something to ponder over. Most held a few monks going about daily chores and a cat or two here and there. And myself and a few Thai. Maybe people who get to Chiang Mai are all wat-ed out, a syndrome that I knew well. But the shady grounds and cool interiors of the grounds made for nice places to sit out of the sun and away from the crowds and traffic on the street.

But there may be another, slightly simpler explanation. If a destination isn't in a guidebook, it might be regarded by many as not being appropriate to visit, or attractive, or even of value. Moreover, as many people simply take a tuk-tuk to a prime spot, they miss out on little things along the way that more peripatetic get to enjoy. Guidebook authors can't include everything, and the better ones leave out a lot of interesting places simply to allow people the opportunity to find something for themselves, to actively participate in their own trip.

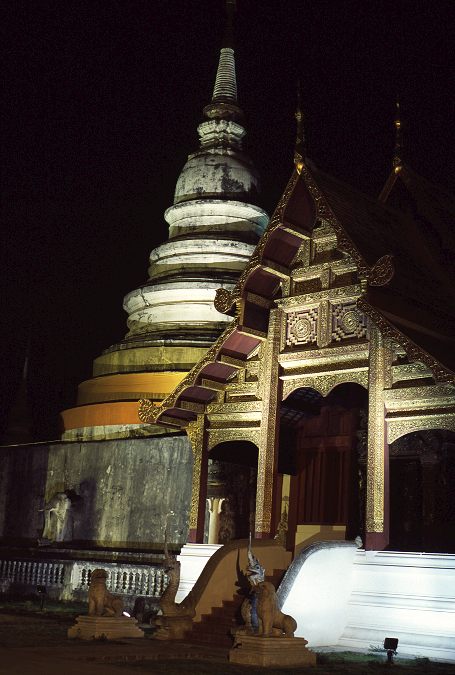

As expected, the central destination of Wat Phra Singh was jammed with tourists of all stripes, both Thai and farang. After all, Wat Phra Singh is a place one can take a taxi to. Who in the world would visit Wat Hua Kwang, given that the guidebook authors didn't bother to include it as a destination? Monks moved about through the mixed crowd of school children and photo-snappers

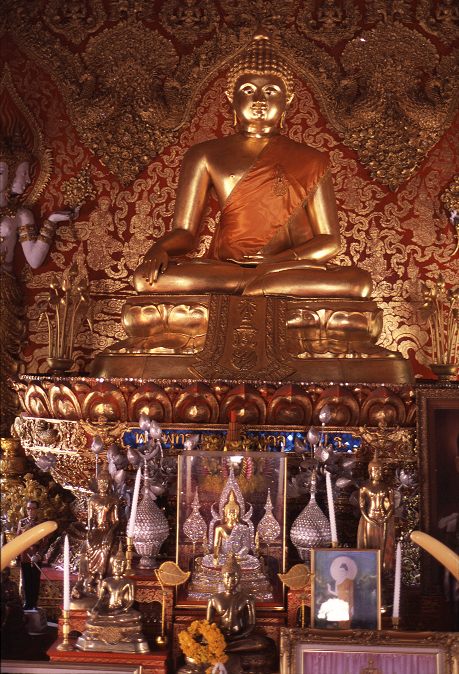

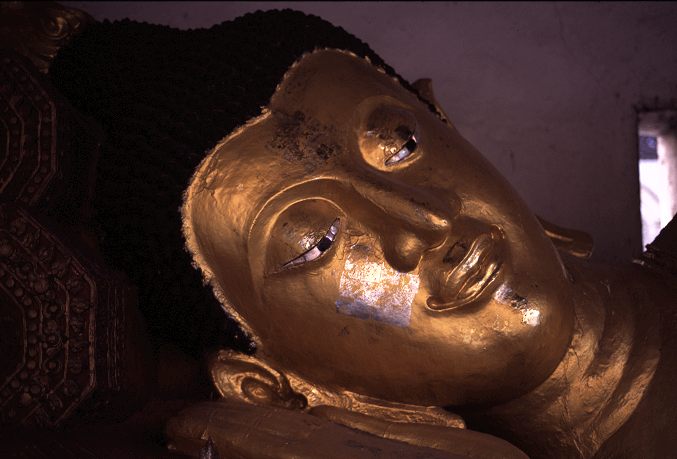

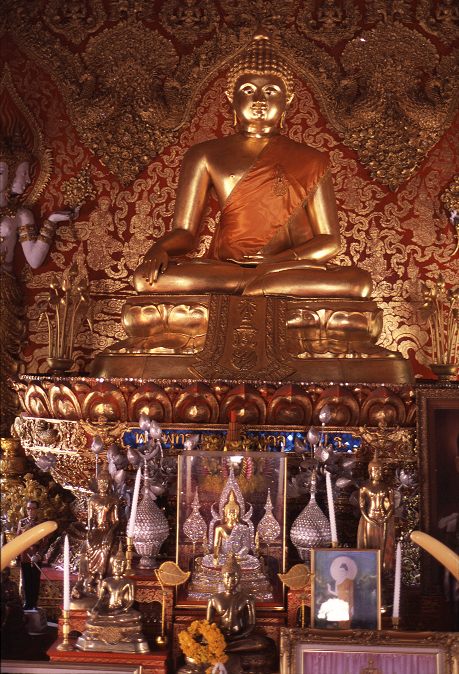

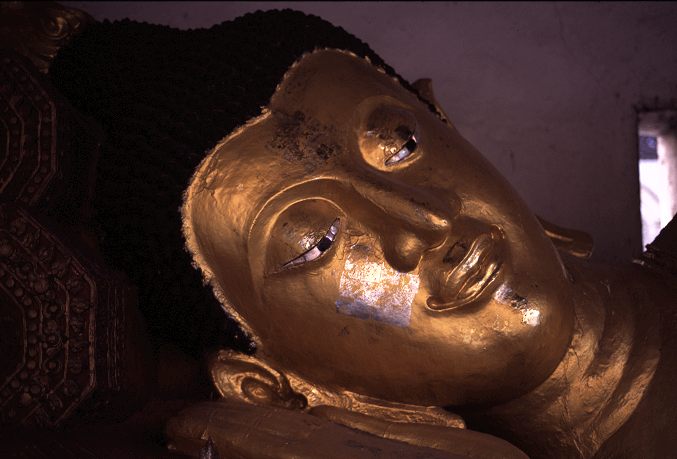

There was much to see in the large complex, but the most interesting features were not, fortunately, the ones with the most tourists. The insides of the main temples held large Buddha displays, but these had all started to look more or less the same to me.

On the outsides of the buildings, though were many intricate carvings, statues, and relief work.

After thirty minutes, I decided that I, too, was wat-ed out and found a man with a fruit cart in order to have yet another sack of pineapple while relaxing in the shade of a tree. As I sat and relaxed, my sweet tooth having gotten its fix, two elderly German women came up to me and began speaking in broken English, pointing at their video camera as they did. I occasionally picked up a word or two, but couldn't quite decipher what it was they wanted of me. Scratching my head, I asked if they wanted me to film them. Not in words of course, as I doubted that their ability to hear English was any stronger than my ability to hear Thai. They moved the camera around so that I could see the display, which happened to read out in English and indicated that the tape (actually some sort of digital media) was full. Two things hit me at sonce: They wanted me to fix their camera and this was what people in the countries I visited had to put up with from me. I looked over their camera, found the right button, and got the old media out. The Germans understood and handed me a fresh one. All fixed up, their were happy beyond belief.

My good deed for the day done, I began the stroll back to the hotel, picking up some postcards along the way and stopping at the same cafe I had last night for another plate of noodles. Paht See Yew was the name of it, I found out, and a delectable plate came out to me in a few minutes. Seasoned up with some sugar and naam plaa prik, the chilis in fish sauce thing, it was truly divine. I was slowly learning Thai by eating in the street, though my vocabulary was limited to food items for the most part.

The afternoon lazed away, spent reading the Bangkok Post and drinking Beer Chang at an outdoor cafe, and as the sun went down so did my activity level. The night meant the night market, which meant my favorite, next to eating, activity was close at hand. I picked up my camera and walked to the main night market, which was only a few kilometers away and led past some interesting wats and many places geared for tourists. I made a quick pass through and stopped at a large seafood stall, with large tanks containing massive prawns. Sold. Cooked up on a wood fired grill, the prawns were not dressed with anything, but came with a small bowl of sweet chili dipping sauce. I completely ignored my burning figure tips as I tore into the succulent creatures that had been alive only a minute or two ago. Washed down with a large bottle of Singha, I had the perfect first dinner. Second dinner would, of course, come a bit later on.

The night market was full, though with far more farang than the one in Phitsanulok. More farang also meant more of the hard-sell, with merchants actively trying to sell me various wares, some of them quite nice. Many vendors had silk scarves to sell and I inquired at a few of them as to the price. Most of the vendors had things that I would never buy, such as T-shirts with slogans on them, such as "No Money, No Honey!". Watches, key rings, purses, and so on formed the most popular farang spots, it seemed. People looking for good deals on things they could buy at home, I suppose.

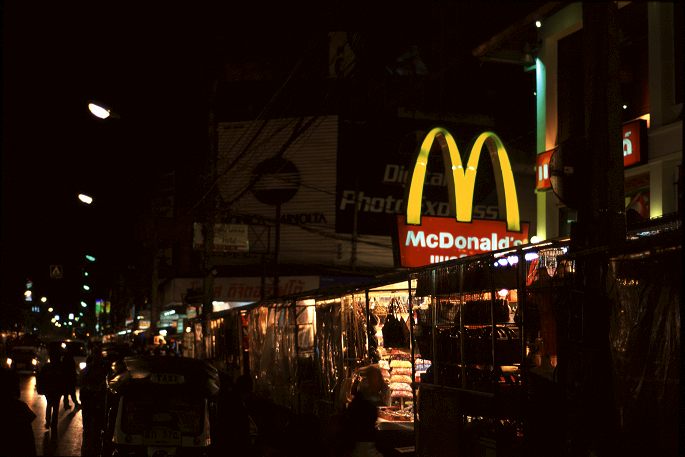

Also popular was the McDonalds, which was across the street and a bit down from the Starbucks, which was popular as well. I slipped into a narrow yellow cafe and ordered up a plate of Paht See Yew, along with a Beer Chang. I was the only farang in there until an elderly European man came in to ask directions, in English. The bewildered cook didn't quite know what to make of this and seemed disappointed he couldn't help the man. Although the market was quite interesting, it just wasn't the same as in Phitsanulok. Perhaps it was the presence of so many families and so many tourist oriented businesses. If the tourists were not here, would the market really be like this? If not, how authentic was it? The market at Phitsanulok couldn't have cared less if I wasn't there: It would still go on as before. Chiang Mai, although convenient, felt a little artificial in comparison. But very comfortable regardless.

As I walked back through the cool (for Thailand) night air, I felt better and better, partly because of the Beer Chang, but also because off of the main street, the vendors stopped selling trinkets. Fewer tourists were met as I took the most obscure route back to the Sumit as I could work up. My musings about the authenticity of Chiang Mai had an elitist air to them that I didn't especially like, even if I couldn't banish them. In the backstreets, Chiang Mai was perfect. It wasn't Chiang Mai that was the problem. The problem was where I chose to spend my time. Thailand, as Chinatown and Bangkok first showed me, has something for everyone. I could choose what sort of experience I had, just as others could decide for themselves.

I awoke early and cleaned up so that I could spend as much time as possible sitting on a teak porch reading the Bangkok Times and slurping down steaming hot, quality coffee in between mouthfuls of khao yom khai at the Libernard Cafe. With nothing pressing to do during my vacation, there seemed little reason to invent something urgent and I sat for nearly two hours in the quite, serene grounds, set far back from heavy traffic of the street. I wanted to head to the outskirts of town later in the day to a forest wat known as U Mong, where I was told I could find some more of the Monk Chat that had so captivated me in Phitsanulok.

I strolled back to the Sumit and grabbed my camera gear before beginning my daily stroll through Chiang Mai, stopping by wats and anything that seemed to hold the promise of interest. That meant just about anything. Wats Chiang Man and Prasat were very pleasant, but I had become rather jaded to wats at this moment: Many seemed to be the same. Perhaps that was why all the wats, except for the famous ones, in Chiang Mai saw so few farang.

But this didn't seem to be quite so strong of an argument to me as I sat in a run down stall along the side of the road eating Paht Thai. There was much to see in the wats, but you had to look for small things, those things that made each one different. Unique. Interesting. Otherwise it was like going to Oklahoma and proclaiming that since all Sooners looked alike, once you have met one you have met them all.

Even if you didn't have the time or inclination to search out the wats for their unique features, they were still a pleasure to sit in, to relax in, to contemplate in. The hustle of the streets, keeping both eyes scanning the road for speeding motorcycles and tuk-tuks, became tiring after a while. After a short walk, a stop in a wat was an opportunity to gain some measure of serenity before resuming wandering. Besides, I thought them pretty.

Around 2 pm I flagged down a pickup truck and bargained my way into a ride out to Wat U Mong, several kilometers outside the city, for 40 B. I could have walked it, but I would have gotten lost and time was drawing near for the Monk Chat. As I've found with long distance hiking, the next best way to see a place (the best being to walk) is from the back of a pick up. We sped past schools, their streetfronts crowded with young Thai in uniform, down a main drag and then cut through winding side streets, bobbing and weaving through a maze of walls, carts, and children, until I was thoroughly disoriented. We stopped in front of a gate proclaiming the entrance to Wat U Mong. Set in a forest, the wat sprawled across several acres of park-like land, providing a haven for nature almost inside of Thailand's largest city of the north.

After poking about the grounds, I entered a tunnel complex whose various twisting, low passage ways led to shrines and displays. A few Thai prayed and moved about. I was the only farang in the complex, but not in the wat.

Upon leaving the incense-filled tunnels, I found the fresh, open air of the outside world to be rejuvenating, invigorating. Several farang couples milled about photographing various monuments in the wat, exactly as I was doing. I was glad to see that people had made the trip out to U Mong, for it was becoming my favorite so far in Thailand. Quite and tranquil, it was a place that urged one to pause for a while and think. And after thinking, to cease the jabbering of the active mind and to simple sit still for a while. At so I stilled.

"First, you must let go of your past."

"Next, try let go of your future."

"Finally, let go of the present."

These were the words that Charles, an Australian who had been a monk in Thailand for the past thirty years, spoke to the small group of farang who crowded around him on a pavilion overlooking a lake on the outskirts of the wat. Charles kept talking, but I was no longer tracking the words that came from him, no longer converting his sounds into ideas. I was stuck on the three brief sentences that he had uttered with the same stillness that you feel on the floor of Death Valley. The same stillness that a solitary snowshoer feels when resting on a snow covered log overlooking a partially frozen tarn. His words bore into me, summarizing with perfect precision the end-goal of how I wanted to live. Neither past, nor present, nor future should you dwell on or hold on to. Value none of them, cherish none of them, know that none of them hold intrinsic worth. Simple words, but difficult to follow. Knowing that old age and sickness are in the future for us all, how can we not prepare for them by saving money, building resources to draw on, planning. Yet they will come anyway. The preparations serve to lessen their severity, not to keep them from us. We all wish to forget our past, yet not to forget the lessons we have learned from it. And how can one let go of the present without also letting go of living in the moment?

Charles was still speaking, and I was still not hearing. I was absorbed in how to really let go without disappearing, without disdaining everything around me, without slipping into the abyss of nihilism. Nihilism was not what Charles meant. I wasn't sure what he meant, but I knew it was not that. On the other hand, I understood what he meant without being able to formulate it. During my long sojourns in the wilderness of the world, I had found that past, present, and future have little meaning from a control standpoint. I had experienced those timeless moments, those states-of-grace, when the unity of existence, including time, becomes so starkly apparent that it seemed impossible that I could not always understand it. Those times would pass and I would fall once again into worries about the future and the present, haunted by my past.

"Attachment is the price of happiness."

Charles had been answering a question that I had not heard, but his answer rang clear. I knew the implications of it. If the cause of suffering is desire, is attachment to things, people, ideas, objects, movements, whatever, if that really is the cause of suffering, then one cannot have happiness without also suffering. There was no Garden of Eden in which we were happy all the time. The focus then, it seemed, was whether or not the happiness that came outweighed the suffering. The monk at Phitsanulok stood in my mind reminding me with his riddle. Was love possible without attachment? He seemed to think that it was. If so, then love and happiness were two different things.

Two and a half hours had passed and I had processed very little of what Charles had said. In between the jabbering of the consciousness, I had heard something of what he said, but none of it rang so loud as to cloud out the two statements that burned inside. I wanted to sit with him and talk for hours more, asking him questions the answers to which I knew already. Rather, I knew what his response would be. He could not answer them for be, but he might be able to point me in a direction, show me a path, on which I might some day find the answers. He had them, not because he had thought about them, but because he had directly experienced them. Moreover, in my heart I knew the path and had some idea of what it entailed. I was afraid to go down it. I didn't have the strength to face the consequences of such a decision. I was still attached to the past, present, and future. I left.

Light was beginning to fade as I started walking back in the direction of town, not quite knowing what I should do. I wanted to walk and think, to forget what I knew and to acknowledge it at the same time. To use the peacefulness of a stroll to sooth my mind and heart. A pickup truck stopped next to me and waved me over. I got in not thinking about it and raced off toward town, staring blankly at the streets around me. The truck dropped me off somewhere. Wat Phra Singh. I walked through a densely packed Sunday market, seeing what was going on around me but not understanding. I should have been blazing away with my camera. Instead I walked along.

An empty bowl of curry and an empty plate of rice, next to two empty Beer Chang bottles, were on the table in front of me. I was somewhere near the Sumit. I remembered the taste of the curry more than I remembered how I had gotten to the outdoor restaurant. Kaffir lime leaves and a rich coconut broth. Strong, minty basil. These things, oddly enough, seemed more real than...than what? I didn't know why I was so out-of-sorts and quickly paid my bill, wanting to run back to the enclosed walls of the Sumit and hide for a while. The night air surrounded me and I stood on the street looking for a clue as to the direction home. I seemed to stand for a very long time before realizing that I was a hundred yards from the Sumit. I don't know how long it really was.

I found a place to hide from the world in the room at the Sumit and means to hide from myself in the form of a bottle of Thai whiskey. I knew from this summer that I couldn't hide from myself for very long. I thought about the Springtime and knew that I had already let go of it. That that part of my past no longer held me. That I was free from it. What I feared was that it would grab me again in the future. I poured another drink.

I awoke disturbed and unrested. I had dreamt of the Springtime, telling it to go away forever. It left in tears and I knew that I had done the wrong thing. I sat on the edge of the bed looking at the the bottle of Sang Som on the table next to me and the Buddhist pamphlet that I had gotten from Wat U Mong, a stack of baht next to it. I sat until I was hungry and went out into the bright sunlight looking for breakfast and coffee, unsure what to do during the day, but not especially caring. I read the paper while eating and then set out to walk to the train station, far on the other side of town, as eventually I would have to leave Chiang Mai and return south for the wedding. I was looking forward to seeing my friends immensely and thought about how far I still had to go before I could let go of the future.

Along the way I stopped in at several wats to rest and to contemplate. The central question of happiness and attachment and suffering dominated as I walked about. The relations and connections, the worth and un-worth. These things, so abstract, seemed so real, just as concrete as the statues and carvings of the wat.

Was happiness worth the attendant suffering? Could there be a balance, or would one always win out over the other? A man and his grandchild provided me with some insight as I was sitting half-lotus inside of one wat.

The man approached me as I sat before the gilded Buddha and sat next to me as I thought. He was visiting his daughter and her children for a while before returning to someplace outside of Chiang Mai where he worked training boxers in Muay Thai, or Thai boxing. We talked of Thailand and where I had been, where I was going, where I was from. We talked about nothing of significance, but when he left I felt all the poorer. It wasn't the words he had said to me that were moving. Rather, it was just his presence. Human contact, human interaction, seemed so much more meaningful at that moment than any construction I could build inside of my mind.

I continued my walk toward the train station thinking about boxers and boxing matches. I thought about the Springtime and what it held for me. I thought about the central question: Can the happiness in one's life outweigh the unhappiness that must come along for the ride? From my experience with the Springtime, I had to say no. Most paradoxically, I would not trade the entire experience for one that was neutral in feeling. The man in the wat provided me with context, with analogy, to understand the paradox. A boxer spends many days, months, in unpleasant training for a match that might last a few minutes. Those months of suffering in training yield, hopefully, to the happiness of Victory. From a balancing perspective, it is better not to train and not to fight, for then one does not have to experience the suffering in order to obtain the Victory. But the boxer knows this and still trains and still fights.

After buying a ticket to Ayutthaya on an overnight train in a few days time, I sat at a plastic table in a restaurant that probably saw three farang a year, eating a plate of green bamboo shoot and chicken curry. I knew that few farang made up the clientele of the establishment, as the food was amongst the hottest I had ever had in Thailand, spicier even than the blazing Som Tom that I could down without issue. I thought about the boxer and the Spring, training and victory, suffering and happiness. Maybe my central question was not the right one to be asking.

I passed hours sitting in a park and a coffee place, thinking about the question. It wasn't the right one to ask and really had no meaningful answer. Suffering and happiness couldn't balance each other out, like sides of an equation or accounting book. I couldn't give myself points for happiness and subtract them when I encountered suffering: The two were separate in the qualities. One was not the absence of the other.

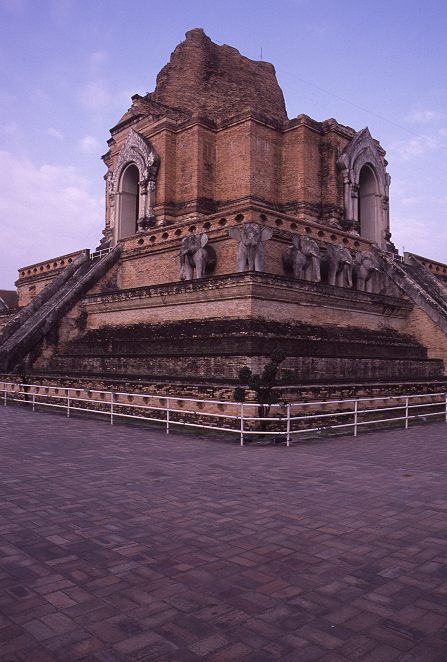

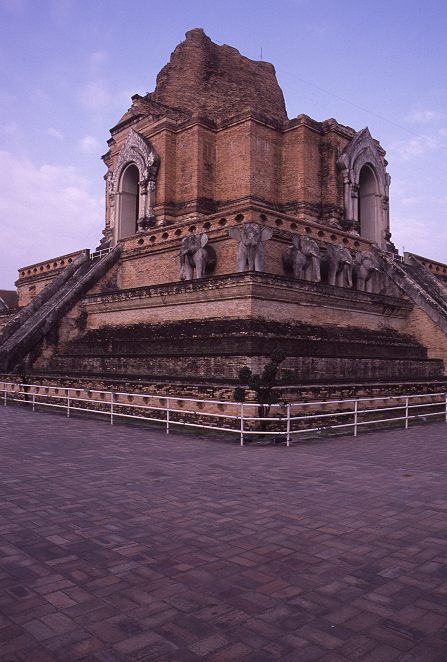

I had intended to return to the Sumit and hide for a while, but got sucked in to Wat Chedi Luang, a massive urban wat, whose top I had seen since I had been in Chiang Mai. More appealing than the more famous Wat Phra Singh, I forgot about questions and balances and metaphysical idiocies strolling around the huge central stupa.

The Buddha, a historical, not divine, figure had pondered the same questions that I had, but unlike myself had found the release from suffering, the key to leaving the world behind. Through the cessation of desire, through the elimination of attachment, one is relieved of the suffering of the world and thus becomes something apart from it. The Buddha also found the right path to move down to achieve this cessation. It was not something to be prayed to, nor something taken on faith. You had to do it to achieve it. This is both very satisfying and very unnerving: Your salvation is in your own hands; there is no divine being that will save you.

I wandered back to the Sumit through the throngs of school children that were getting out of school and racing for the carts of local vendors selling sweets and drinks, giggling and laughing as school children do. At least school children outside of the US. I didn't see this same happiness when I was at home, and that saddened me. Despite all of our enormous resources and staggering wealth, we didn't even have happy school kids. We had frightened school kids, morose school kids, and terrified parents, quick to medicate their offspring to the point of numbness. I was glad that I hadn't hid back in the Sumit, but had stopped at Chedi Luang.

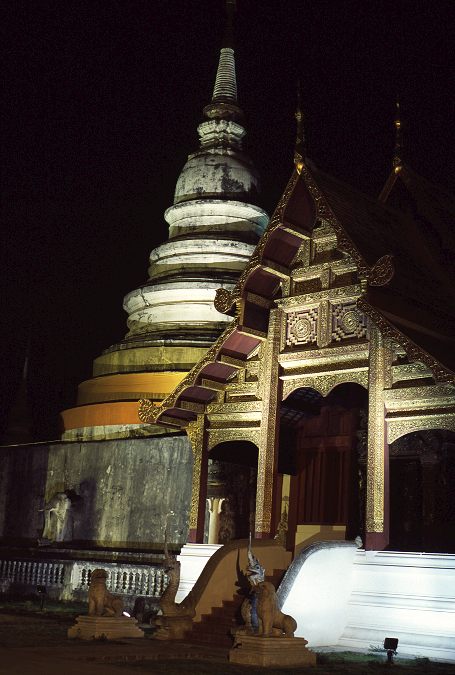

The afternoon hours passed and the light began to wane as I ate a plate of noodles across the street from the Sumit, watched the land grow dark on me, wondering what my fellow farang would be doing tonight. Some would be with their families inside of hotel rooms. Others heading out for a drink at a night club. I was heading out into the dark night looking for a plate of something tasty. I wandered the streets of the city, stopping off in various places to snack and to eat, and eventually found myself inside Wat Phra Singh.

There were no farang at this late hour and a Buddhist ceremony was going on inside the main temple, the sounds of chanting pouring forth from inside. I walked about the grounds and found a comfortable place to sit in the dark. I sat and did little other than point my camera at the buildings around me, happy to be anonymous, unseen, an unknown entity hiding in the shadows.

"It is beautiful here at night, eh?"

The voice came to me out of the darkness of the grounds, though it oddly enough neither startled nor scared me. I turned in the direction of the sound and could barely make out of the form of the speaker. The accent was not Western, but that was all I knew about my interlocutor. I agreed with the speaker, thinking about my experiences in Yellowstone last summer, wondering if this was really happening to me.

"What does your camera see at night that you do not?"

I couldn't answer, despite knowing many different, standard responses to the question. The speaker was right, and I tried to tell him so. I couldn't tell what impact my words had on the speaker. I couldn't even tell in the black night if he moved, or was even there any longer. A moment of unknown duration passed and he wished me a goodnight and was then gone. I wandered back through the night, giving directions to a drunken Australian who couldn't find his guesthouse. He had been drunk the night before and didn't remember the way. I showed him my map, though this did little good as he had no idea where he was and even less of an idea in which direction his guesthouse was. He produced a card with the name of it and I suggested he hail a tuk-tuk. This seemed like a great, wonderful solution to his problem and he quickly moved off to the edge of the street, waving at the passing cars. Chuckling, I walked back wondering about the reality of the speaker in the shadows. I didn't really matter, I thought. What mattered was what I did in response.

Sitting in the UN Irish Pub while eating muesli and drinking coffee, I could have been anywhere in the world. Only the lithe Thai waitress and the Bangkok Post indicated a specific position in the world. Just sitting in the outdoor section of the pub was a treat. I had no routine, no schedule, no responsibilities. I was also quite alone. As the spirit moved me, I set out on a walking tour along the northern edge of Chiang Mai, with no particular destination in mind. Just moving. Just seeing. Just being. I found myself in a hole-in-the-wall, whose blazing pork curry indicated a distinct lack of farang as customers, wondering how I would get to Doi Sutep, for I had to go. The elder monk in Phitsanulok told me that it was important that I make the trip to the wat, sitting on top of a large hill outside of Chiang Mai.

After eating the impossibly delicious curry, I wandered out into the street and flagged down a pick up truck for a lift out to Chiang Mai University, near which, my guidebook told me, was the main jumping off point for trucks up to the wat. In actuality, this turned out to be several trucks on the side of the road, a few bored drivers, and a sign telling me the price and that trucks would leave only when there were seven passengers. As I was the only farang in sight, it seemed that it would be some time before the requirement was met. I had a seat next to the drivers and relaxed in the shade, making small talk as I could. About every twenty minutes one of them would ask me if I wanted to pay for all seven seats and get a lift up. As I had a lot of time on my hands and very little to actually do, I just sat and watched the traffic go by. I actually enjoyed sitting alongside the road, waiting contentedly, and not dwelling on when I might actually get up the hill, for without a schedule and with a chair, one can accomplish miracles of patience.

After an hour, three Thai university students walked up and spoke to one of the drivers for five minutes before waving me over. I had a ride up for the normal fare, mostly, I think, because of the boredom of the driver and his hope that he might be able to find more fares for the ride down. Whizzing up the road to the wat, the three students and I engaged in a rather broken conversation in English, as my Thai was good primarily in food stalls. They made the trip up to the wat every year to pay their respects, I think, though I couldn't figure out to what. Slightly queasy from the winding road, I was glad to hop out of the truck and start up the long staircase with the three students, heading finally to the wat itself.

The students were winded and tired when we reached the top and were on their way to pray, so we parted ways at the entrance, though I was not alone: The wat was popular with locals, who far outnumbered farang.

Doi Sutep was much like the other famous wats of Thailand that I had been to; if I hadn't been to many places just like it, I would have been overwhelmed by its beauty.

As I had learned to do, I went in search of the things that would made Doi Sutep unique. Some of these, like the the expansive views down in the haze-choked valley of Chiang Mai were obvious, though not especially appealing. Some came to my mind because of their sound, like the long row of bells that were struck by the faithful from time to time.

Others came to me via my nose, such as the sweet smelling flowers and flowering trees that lined the perimeter of the wat.

Others because they seemed incongruous at first, but later expressed part of of the Thai culture that was making such an impact on me.

I walked about the grounds for some time, making not one but three circuits to see what I could see, mostly ignoring the larger, more "important" structures in search of uniqueness. I came upon an old tree wrapped with a golden silk, the significance of which was lost on me. But the simple beauty was not. For many reasons it did not matter why the tree was wrapped, though I wished someone could tell me the answer. I only knew that it was one of the few times that the hand of man had modified nature to create something more appealing to me.

I had spent an hour or so wandering about the wat before heading back down the long stair case in search of some food and a ride back in to town. Doi Sutep had not made the same impression on me as the monk in Phitsanulok, or my experience at U Mong, or even my night time friend from Wat Phra Singh. But it had been, at least, an agreeable afternoon.

The ride back into town was just as twisty as before and I was happy to hop out on the outskirts of Chiang Mai and walk the rest of the way back to my neighborhood, taking a long, round-about route through a new part of town. I had nothing left to do in Chiang Mai, nothing in the guidebook seemed appealing, and it was only the mid-afternoon. I was on my own for entertainment. I found it in the form of the kind woman owner of a pub called The Mask, around the corner from the Sumit. As I swilled beer and ate Lap Gai, a spicy salad made from chicken, we talked about various topics, none of great importance, but holding great pleasure for me. Like Nasser in Tripoli and Kemal in Damascus, Flora (not her actual name, but rather my interpretation of it) gave me perspective by allowing me inside of a part of Thailand that you cannot get from a book or on a tour. It wasn't that Flora was looking for money. Rather, she just wanted to get to know me, to hear my stories, as I wanted to know her and to hear hers. I couldn't offer anything else to her. After a few hours I said my goodbyes, telling her I would be back the next day, and headed out into the now-dark night air of Chiang Mai to wander the streets for a while.

I found myself in the compound of Chedi Luang making circuits around the main structure, lit up with a mellow golden glow that heightened the beauty. A few others were strolling about in the darkness, a few cats ran here and there. I was content to wander and point my camera, to think and ponder. And eventually just to sit in the darkness. To sit and be still for a while, despite knowing that I was going to have to leave eventually. I would have to leave Chiang Mai in a few days, leave Flora in a few days. And eventually leave Thailand. But that was the future, and I was supposed to try to let go of that and simply be still.

The waitress at the UN Irish Pub didn't even have to bring me a menu or ask what I wanted. A cup of coffee and, a few minutes later, a bowl of museli, fruit, and yogurt showed up to accompany the Bangkok Post that I was reading. The morning routine in Chiang Mai has been pleasant, to say the least I can about it. Two hours of breakfast was a treat that I could never seem to indulge in on a regular basis while at home.

After my morning leisure, I took my morning constitutional by walking over to a large market, teeming with Thai and few farang. There was a little for a farang to buy here and going to it was about the equivalent of a Thai visiting Wal-mart: A cultural experience. I tired quickly of the market and headed to where the night market was, but found little that of interest as no vendors had set up in the early afternoon and so headed back to the Sumit, pausing briefly to listen to the cat-calls from a group of women lounging in front of a pub, and actually stopping for coffee at a Thai version of Starbucks, called Black Canyon Coffee.

I was struggling to find something to do and so, after a cat nap back at the Sumit, walked over to The Mask to see if Flora was about. Indeed she was, along with her son and brother, both of whom she introduced me to. She joined me at my table and as I swilled Beer Chang, talking about the US and how foreign men view Thai women. She seemed especially interested in this last topic, which was a little difficult to talk about despite her excellent English. Affairs of the heart are rarely simple enough to break down into easy words without using allusion or metaphor. I spent a few hours with Flora before the Mask started to become busy once again with the onset of the dinner crowd and she was called back to the business of running a pub. I set out into the darkness for the night market.

In contrast to the afternoon, the night market was in full swing when I arrived. Vendors were set up and busy hawking their wares, from food to watches to handicrafts. I stopped at a stall to look at the silk scarves for sale, taking advantage of the missing vendor to look over the goods for a bit without pressure. After a minute or two, the grapevine must have passed along the message for a miniscule Thai girl, not older than fourteen, came running over and the haggling began. All over the developing world the same conversation was taking place.

Me: "How much?" (pointing to one scarf)

Her: "For you, special price" (shows me a calculator with the number 200 on it)

Me: "For small scarf? Too much!" (trying to look hurt)

Her: "How many you want? I give you good price." (trying to look hurt)

Me: "One scarf only." (I want four)

Her: "You first customer tonight. I give you special price. How much you pay?" (she knows I'm lying)

Me: "I give you..." (enter the number 100 on the calculator)

Her: "Eye!" (she enters the number 175)

Me: "Maybe I'll get this one also. How much?"

Her: "You first customer, get special price." (enters the number 330)

.

Me: "Eye! Too much!" (I enter 200, look hurt).

Eventually I left with four scarfs, three small ones (about the size you'd wear) and one large one, for 500 B. Although I could have paid left, my skills at haggling are only so developed, and in the end we would have only been arguing over a dollar or two. I had done my part and gotten what I wanted for a reasonable price. She had done her part and had sold at what she thought a reasonable price. Someone on the outside watching the spectacle (6'4", 200 lb bearded farang haggling with a 4'8", 80 lb Thai girl) would have found the scene rather comical, as indeed I did. Happy, I went in search of food.

In the main food vendor area, I found place serving up sizzling mussel omelets, whose delights I first experienced in Bangkok with Wallapak and Sandra. Unlike a traditional French omelet, the Thai omelet is more like scrambled eggs, fried up into an amalgamation with scallions, bean sprouts, and copious amounts of oil and tender mussels. Served with a sweet chili sauce, it made an excellent appetizer to go along with a bottle of Beer Singha.

From the evidence in front of my eyes, and conforming to what I had experienced in the past two weeks, the Thai love to eat and the courtyard was jammed with families, groups of pre-teens, and collections of businessmen. Rarely were there solitary diners, except for the one or two farang that I could see. We were a rare breed here in the part of the night market devoted to food. Perhaps farang were scared of getting something from the food and so trusted to restaurants, where the food was prepared behind the scenes, instead of in front of your eyes. After all, isn't it a cardinal sin of travel to eat off of the street? Perhaps the lure of McDonalds was too great, drawing people to eat french fries and hamburgers.

I had little to do tonight except try to see Flora again and so made a long stroll through the market, wondering why there were so many farang buying T-shirts instead of mussel omelets. I decided that it wasn't for me to know this and contented myself by buying some chicken-on-a-stick, making my own choice, just as the T-shirt buyers were making their own. Walking down the dark street, eating the satay, I couldn't have been more at home.

Ah, moving day. An opportunity to go someplace new and different, to see and do new things and meet new people. It meant leaving a comfortable place and separating from those I knew, but at 10 pm a train was heading south and I meant to be on it. I had to check out at noon, which gave me a lot of time to do nothing in town. After my normal morning routine in Chiang Mai, I headed out, with my pack, to Wat Lokmoli, finding one of the nicest wats in Chiang Mai.

The quiet grounds, with their flowrs and shrubs and monuments, exuded compassion. Equal in most ways to the higher profile wats in my guidebook, but given only a marking on the map, Lokmoli was good for an hour of strolling and sitting. Except for a Thai family, I had the place to myself. The Lonely Planet had to be doing this deliberately, I thought. There was so much good stuff that they didn't include as a "sight" that it couldn't be accidental. That is how a guidebook should be: A start, not a dictionary.

I spent the rest of the day wandering through Chiang Mai, revisiting a few final places, seeing a few final sights. After hours of wandering, I found myself again in The Mask eating dinner and drinking beer and talking with Flora. Of all the things I had done in Chiang Mai, perhaps it was knowing Flora that I cherished most inside of me. A wat is just a wat, but a person is more than the sum of her parts. When my time came, and it was quite dark outside when it did, I left her for the night air and the uncertain future, walking toward the train station and the future.