Needs

Slate Canyon: Grand Canyon National Park, March 25-28, 2006

March 23, 2006

I should have been tired and weary and unhappy and uncomfortable, laying on top of hard snow on a dirt road somewhere in southern Utah after having driven for 17 hours down the mind numbing interstate highway system. I was thrilled to be where I was, when I was. I had left Lakewood feeling caged, soft. I had left Lakewood uncertain as to what the Spring would bring for me, for it had been an early Springtime indeed this year, starting in early February this year. ÊI needed to leave that place and live on a more primal level for a while, to live without doubt or hesitation or constraint. To live instinctively, intuitively, instead of rationally, analytically. To live directly, as Thoreau once wrote.

As I sat under the impossibly bright stars at the edge of Red Rock Country, on the border of Abbey's Country, drinking a can of beer, I realized that everything that had been weighing on me was, for the next ten days, somewhere else. The feeling of space, here under the stars, was intoxicating. It had been some time since I had been able to be in the middle of nowhere, completely alone, and not feel lonely. I grabbed another beer from the snow holder that I had fashioned to chill the cans and wondered how people could live otherwise. Not sleeping by the side of the road in a desert drinking cheap beer, but rather how they could live confined, their lives dictated to them by obligations they themselves had taken up. A crushing mortgage. A boring, but high paying, job in order to pay the mortgage, support the family, buy a wide screen, plasma, HDTV, purchase a time-share in Hawaii that would never be used, keep up with the Jonses. Not putting down roots, but rather settling down like mud to the bottom of a pond, as celebrated Himalayan explorer once wrote. Nine months ago this was what I thought I had wanted, at least temporarily, this settling down thing, that is. That time had passed, and yet the Springtime lingered inside of me, unwilling to leave on its own, and I equally unwilling to completely let it go. I needed this time away from everything, I needed it more than I had ever in the past. I knew that when I returned the Spring would be there, but that now I had some refuge from the its turmoil, from its charms, from those things that were so drew me to it. Ten days without conflict, away from the war without end.

The early morning light woke me as it turned the mountain sides around me a preternatural yellow gold, mountain sides that I hadn't even known existed in the blackness of last night. I collected the empty beer cans around me and quickly tossed my sleeping gear into the trunk of my car before roaring down US 89 in search of coffee and breakfast in Kanab. I hadn't showered in two days and I was beginning to sport something approximating a gritty beard. With old jeans and a fifteen year old baseball cap, I looked rather run down, as the owner of the cafe I ended up with couldn't fail to notice. A plate of huevos rancheros, the best I'd ever had, came to me in the cafe, with only a few others about, along with a steaming hot cup of coffee and a smile. Thinking me a local that was down on his luck, waiting for the summer tourist season, and hence regular employment, to begin, she kindly offered me a thick discount. Warmed inside more by this than by the outstanding food I, too, smiled, and offered that I was just passing through on my way to the canyon, but I appreciated the offer.

Having driven so hard the day before I reached The Most Beautiful Place on Earth before noon and found my way to the Backcountry Office to modify the permit that I had reserved six months before. My friend Sandy was coming along for this spring's trek, which was much more ambitious than the one she had been on two years ago down to the confluence of the Little Colorado and the Colorado rivers. Sitting behind the counter was a young man that seemed familiar to me, and I to him. After a few questions were exchanged about water sources and route finding on the Tonto West and South Bass trails, it became clear we knew each other. Spidermite, as I knew him, was at last year's ADZPCTKOP with some friends of mine and we had spent time during that hikertrash festival. He was working as a ranger in the canyon for the spring and summer seasons, and probably hoping to stay on after that in some sort of permanent capacity, at least until a long walk called to him again.

Permit in hand, I drove to Mather campground and threw up a tent for the night. I had hours to kill before Sandy showed up, which I spent on my back, a beer resting on my belly, doing what people do during vacations. The campground was empty, with most of the inhabitants off day hiking or driving from front country site to front country site "doing" the canyon. Part of me, the uncompassionate part, didn't especially care if the gawkers among them wasted their time ogling the canyon from above for a few minutes before driving off to some other ogling viewpoint. They could ogle to their heart's content, just as they could over a picture book at home. Ogling a picture book is in many ways better, for the photos are taken by professionals in exactly the right light, with precise skill, and amazing artistic ability. And no line for the bathroom. As long as they didn't choke the backcountry (as if they could step off a paved trail), I didn't mind the traffic jams they caused. Even if they all fled to the backcountry, the Canyon is a large enough place for all.

On the other hand, the more caring part of me wanted them to experience something they couldn't get from a picture book. It was something they would have to step off the paved trail in order to get. No amount of pictures or overlooks could show the true qualities of a place. No amount of skill will allow you to judge a book based on its cover. No amount of skill will show you the heart of a woman based on her figure. You need time to discover all three. But time is something most people choose not to have, just as they choose to surround themselves with the shiny things that are so well marketed to their specific age-gender-income level-geographic area-education type-political affiliation-religious inclination. Advertisers are, if nothing else, clever. I felt sorry for them just as, I'm sure, they felt sorry for me.

Sandy arrived in the early last evening after making the drive down from her home in Salt Lake City and we had spent a pleasant few hours together eating dinner and catching up after an absence nearly a year. We spent an hour going over her gear and food and getting everything packed up before hopping on a shuttle bus to take us out to Hermit's Rest and the start of the Boucher Trail. My plan was to hike down the Boucher to the river, then over on the Tonto West route to the South Bass trail, then up to the South Rim and a 28 mile dirt road walk back to the cars. With no day over 15 miles, and fairly gentle elevation gains, and even a basecamp day for exploring along Huxley Terrace, it seemed like a fairly simple plan to me. There was some question of where we could find water along the South Rim walk, but there seemed to be enough tanks and cattle troughs that it should be an issue. We'd hit at least one water source, about in the middle, of each day's hike and could camp at a source every night. As far as desert hikes go, this was fairly easy, though Sandy seemed rather nervous about being separated by as many as eight miles from water.

I tried to reassure her that thing generally work out for the best, and even if they didn't on this particular occasion it wouldn't be a big deal to be thirsty for part of a day. Still, the sense of going outside of her own comfort zone into an unknown area was a bit daunting. I couldn't tell her for sure where water would be, or how long it would take to get to it, or how bad the side canyons would be, or how much scrambling we'd have to do, or how many people we would see, or if the water would be salty, or if someone might give us a ride on the South Rim road, or if the tanks would be full, or if it would take one or two days to get out, or if the route was well cairned. I didn't mind not knowing, for I knew that something would work out. She didn't know and she did care. Fortunately, the weather was good at the start and I was on known ground for now, going over the start and end of my first Grand Canyon hike.

As we descended the massively built Hermit's Rest trail, the majesty of the canyon made itself apparent, just as a slap from a sledgehammer would. The Canyon is a vertical world and the agony that the first explorers must have gone through to reach the river was impressive. Plateaus and escarpments are easy to traverse, but at some point one must descend, and finding good places to do so is not especially easy. The Hermit dropped us down to a butte, from which point we began the long, mostly level traverse around the walls of the canyon heading for the point where the Boucher makes its plunge to White's Butte and eventually the river.

Our blue skies had faded into a mass of white a few hours into the hike, but no rain seemed to be present in them, at least for us. Sandy was thrilled beyond belief, as I was, to be out of town and away from things for a while. Though she had initially loved Salt Lake City after our shared confines of Champaign, Illinois, three years there had been enough. She had not been able to make the connections with the people there that she had wanted and had grown tired of feeling like an outsider. Away in the Canyon with a friend was what she needed at the time, just as I needed to be without responsibilities and obligations and worries. That these two needs might be in conflict with each other crossed my mind, but only in the briefest of time spans.

We picked up the Boucher Trail proper, after cutting over from the Hermit on the Dripping Springs trail, and made good progress on our traverse, stopping for lunch on a slab of rock overlooking the beginning of the plunge downward. Three years ago I had climbed up the steep, though well marked and passable, route after spending a night in a wind and rain storm next to White's Butte.

After filling up on lunchables, we started back on the trail. I moved slowly, knowing the Sandy was shaky on rocky, steep descents, as indeed most hikers are. The footing seems so much more precarious than when you are trying to gain elevation that, almost involuntarily, one uses one's quads far more than necessary. As a result, one's legs quickly turn to jelly and the problem is amplified.

The worst of the descent was at the start for us: A short, twelve or fifteen foot scramble down some rocks that had proved easy to climb up three years ago, even in the rain. I moved down the chute to show Sandy the way and then waited for her at the base in case she needed a helping hand. Although nervous about it, she managed her way down without problem and got back to the trail, happy to be on slightly level ground once again.

With the worst over, I moved out in front of Sandy at a comfortable pace, knowing that it was best for her to make her own way over the rocks at a pace that she was confident at. I did, however, keep her in sight in case something unfortunate happened on the way down. The clouds gathering overhead were looking more and more ominous and I didn't especially want to get caught on the descent on the other side of White's Butte in a storm. I did, however, feel that I had to wait for Sandy before beginning the next descent, for she was worried about losing the trail, despite my having given her a map and the trail descriptions from the park service. And so I sat for twenty minutes next to the butte watching the skies darken.

Sandy's legs were quite tired and she was running out of energy. The nearest water was Boucher Creek, near the bottom of the descent, which meant that camping at White's Butte really was out of the question. We would have to make the next descent. Climbing up the gully to White's Butte, the route we were to begin presently, had broken the three friends I was with in 2003. If going down is harder on the legs than going up, the future didn't look especially good for Sandy's jellified legs.

Beginning at the notch, the trail leads down into a brush choked gully, plunging as quickly as possible to get out of the restricted space and on to the wall where walking is easier. Within a few minutes I was already far from Sandy and, knowing that she would be nervous if I was out of sight, I stopped to wait for her on two minute intervals. The clouds were growing darker and certainly held rain of some sort, though whether or not they would decide to drop it on us was another question. I reached a trail junction after thirty minutes, with five minutes of waiting, and had a seat out of the wind, not wanting to risk having Sandy go in the wrong direction at the junction in her tired state. Five minutes passed. Ten. Twenty. And still no Sandy. Becoming a bit nervous myself, I walking briefly up the trail and stood, hoping to catch a glimpse of her as she came down the trail. I eventually spotted her on the cliffs above, waved, and returned to the junction, which she reached ten minutes later, completely exhausted.

I had already scratched the plans to camp along the Colorado River, for I did not think she could make it much further. We simply needed to reach water and then find a flat spot to camp and we could end the day. Boucher Creek wasn't far, as I remembered, and so after a short rest we pushed on, this time staying together on the descent, which was far easier than the drop from White's Butte. Within a few minutes we heard the sound of running water and saw the source a few minutes after that. Now, just a flat spot was needed. Ten minutes down the trail we found ample spots, along with a group of four utterly whipped men, who had also planned on making the river. There was room for all and we found a nice place close to the creek spacious enough for both of our tarps. I got Sandy's set up, and then mine, as Sandy fetched watched and did other camp chores, knowing that once she stopped completely, she would be done for the day.

We had an hour or so of daylight left to cook and eat in, which Sandy managed to do despite not having an appetite. Anyone who has put in a physically challenging day knows that hunger and the desire to eat vanish completely. Sandy, however, was smart enough to know, without my prompting, that she had to eat to give her body the necessary fuel to repair itself and prepare for tomorrow. Once dinner was finished, however, she was asleep and I was alone pondering what would happen during the rest of the trek. We had taken twice as long as I thought it should taken and Sandy had arrived with nothing left physically. Rather than being free to roam about as I saw fit, I was instead spending a large portion of time waiting for her or making sure she was alright. She had ended the day happy, for she was far tougher than to become depressed over a bit of hard work, but I doubted whether or not she would be able to make the full trip without becoming so. And, moreover, I doubted whether I would enjoy being relegated to the roll of guide, having to watch over her constantly and re-assure her that everything would work out. It wasn't what I needed at this point. I needed the freedom of the backcountry. A few hours after Sandy went to bed the stars came out in glorious fashion, giving, as they always do, a feeling of hope to my otherwise doubting mind. My hope, though was misplaced, mere stargazng. Sandy wasn't the one depressed after day one. I was.

I could see the morning light glowing on the wall in front of us, but our sheltered area in the drainage was still quite dark. I wasn't sure what was going to happen today, but thought it best to give the hike a shot and see how things turned out. I wanted to walk along the Tonto Platform in freedom, enjoying a land more powerful than any I had ever been to, enjoying a moment of my life spent living directly.

We packed and filled water for the traverse over to Slate Canyon, about five miles distant, where we had been told there was a very reliable water source. Five miles wasn't especially far as these things go, and other than a few hundred foot climb back to the platform, most of the day to Turquoise Canyon should be flat and easy walking. Sandy's legs were sore from yesterday's descent, but I hoped that with movement they would loosen up and be alright.

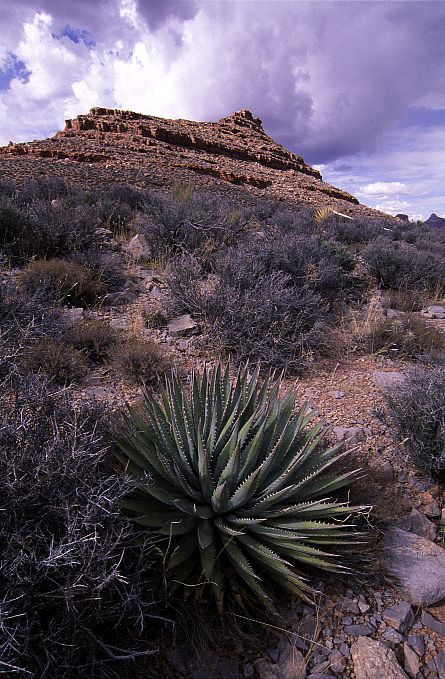

From our camp the trail disappeared, but it was clear where to go: Straight down the drainage heading toward the river. Not having a trail had long since ceased being a point of worry for me, as the drainage was easy to follow: Just walk along the water. Sandy was a little less thrilled about this prospect, but I tried to keep her in sight and maintain a confident aspect. Perhaps a half mile down the drainage we found cairns that indicated our drainage walking was over and the Tonto West was beginning. After the brief climb, we emerged onto the platform under impossibly blue skies. Marsh Butte, on the other side of which we had camped thrust itself up to our rear, while we faced miles of spectacular flat hiking. Perfect. Glorious. My fears and depression were gone, for this was a trail that anyone could walk.

Unlike previous canyon hikes along the Tonto, this one seemed to be almost prarie-like, with large amounts of open space and a trail that had zero exposure: No air was to be found underfoot. Sandy and I quickly separated, but remained in sight, as my longer stride and enthusiasm brought me forward with a rush of anticipation for what the day might bring.

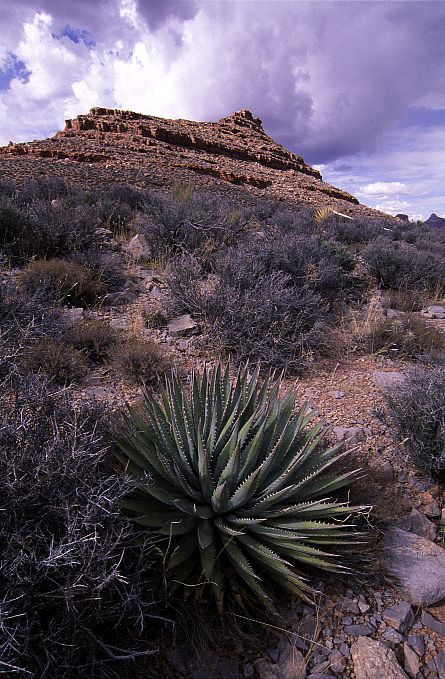

Even accounting for a slower pace and more rest breaks, I didn't thing the distance to Turquoise Canyon would take much time at all. Perhaps in by three or four in the afternoon, with plenty of time to gather water and explore the canyon itself. After a break with Sandy, we began the push into Slate Canyon, which my map showed as being very deep. Scylla Butte was on the other side of the side-ditch and made for a prominent land mark to judge progress, or lack thereof. As we ran down one side of Slate, we encountered, much to my surprise, two backpackers coming from the west. They were reversing our route and taking twice as much time to do it in, and were having an absolute joy of a time. They brought excellent news: Water was flowing about everywhere, bighorn herds had been spotted, and cougar tracks found. After my depression of last night, this was very good news indeed. Water would not be an issue inside the canyon and there would be much to see and stalk along the way.

Sandy, however, was not feeling well. Her tired legs had not loosened and she was exhausted already, despite the flat hiking. It wasn't from the exertion of the day, for we I hadn't broken a sweat yet, but rather a carry over from the day before. We talked as we went and I began to face the decision that I had hoped would disappear with yesterday's clouds. We were no longer compatible as hikers. She would either have to death march to follow me, or I would have to play guide with her. Neither was acceptable. Sandy couldn't function independently in the canyon in a way that would allow her to enjoy her time there and needed me to be there with her, remind her when water was coming up, when to drink, what to eat, and so on. She needed a different kind of trip than I did. We found the water coming out of Slate Canyon and sat in silence eating some energy bars and drinking water as I pondered our options.

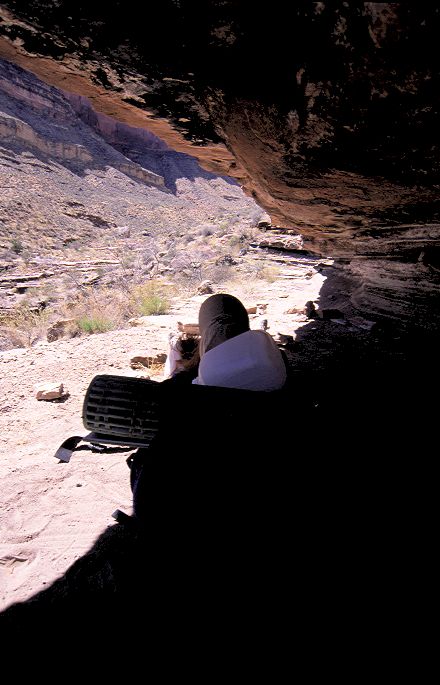

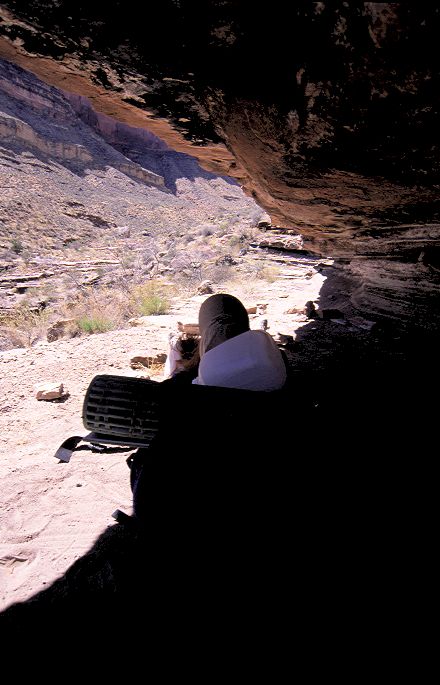

There seemed only one good one, and that was to turn around here. My trip, planned months in advance, salivated over during the rains of a Pacific Northwest winter, was done. I couldn't in good conscience drag her forward. She would, most likely, be able to tough out the rest of the trip but would not enjoy herself. The physical strain and the mental effort were going to be too much to relax. Moreover, I didn't want to put my friend through that or play the role of tour guide. After our break, we recovered the trail on the other side of Slate Canyon and I stopped us under some shady cliffs to lay out the scenario. At 11:30 am, we decided to stay the night under the cliffs and then retrace our steps over the next day and a half, camping at White's Butte along the way. I wanted to weap as Sandy laid down in the shade for a nap.

I wandered about exploring our environs and working on my tan, wondering what places like Turquoise Canyon or Bass Rapids looked like. Wondering what Spencer Terrace might hold. About an opportunity missed that would not return for another year at the least. After an hour or so I regained my composure and returned to the cliffs to nap in the shade as well.

My nap was to be short lived, as quickly two hikers were heard also coming from the west. I had been told that this section of the park was the most remote, least travelled of any on the South Rim yet we had now met four hikers. Not exactly a traffic jam, but far more than the number of people I had seen last year along the Escalante Route. The two hikers were also doing our route in reverse, and also taking twice as long to do it. Although it was already two in the afternoon, they had camped only two or three miles from here and would spend nearly four hours by the water of Slate Cayon before moving on. It wasn't the difficulty of the route, it seemed, but rather people wanting to spend more time in camp or resting than walking. Different needs. After chatting for a while, the hikers moved on to the water to wash and drink and make dinner, leaving Sandy and I to sit and chat in the shade. As the afternoon advanced, two more hikers, this time from the east, came into Slate as well, forming one of the largest collections of hikers I had ever seen in one place in the Canyon.

The two young women held the distinction of being teachers at the elementary school in the Grand Canyon. Not outside, but inside the park there was apparently an elementary school for the children of employees of the park and the various private companies operating in and around the park. Sandy was chatty with them, telling them of our plans (they thought it insane, but given the massive sunburn and blisters on them, they didn't seem to be even remotely experienced in hiking) and in general enjoying herself. I mostly tried not to be dour.

As we were leaving to return to our cliffs and cook dinner, Sandy spotted something that both of us had missed: A couple of cougar tracks right next to the water. We had seen some up-canyon while searching for the trail, but these were right on it. I have never seen a large cat in the wild and doubted I would today, but the tracks were nice to see anyways.

Cheered, we returned to the cliffs for dinner and to watch the stars come out. Although things could have been better, life was pretty good in Slate, with plenty of water and interesting rock formations to play about on. An a bottle of overproof rum to go along with my dinner. Tomorrow would begin our retreat out from the Canyon and the Tonto West, which was almost sad enough to spoil my mood. But not quite.

A day of retreat. At least it would be easy, with only one moderate climb up to White's Butte. And short. But not pleasant for most of the way, for retreat is never enjoyable. The trip was now about Sandy's needs, rather than my own. A year ago I couldn't have accepted this with anything other than malice, but I had grown since then and I held no ill feelings, though my heart was sad. We set out for the five mile walk back to Boucher under cloudy, though non-threatening, skies.

We met the two backpackers camped along the plateau, just finishing breakfast, ensconced in a campsite with a wonderful, open view, though we didn't stop to talk for long. As we rolled along I lost the trail in a drainage, missing the correct exit point, and hiked up rather than along. Realizing that I had lost the correct path, I struck out cross country, not thinking anything of it. For, given the topography, there was only one place to go and the general location of the trail wasn't in dispute. I shouted down to Sandy that I was off trail and either to follow me or find the exit point below. That settled, I walked over a mild ridge and descended to meet the trail. Not wanting to get too separated, I sat and waited.

Thirty minutes passed and I was feeling rather annoyed that Sandy had not yet appeared. I put my pack back on and stomped down the trail, shouting out her name as I went. A few minutes later I found her pack sitting by the side of the trail, but could not find her. I shouted her name several times, but got no answer. On the verge of losing my temper for the first time in years, I stood on my feet, rooting myself to the earth, and waited. Five minutes later, she appeared, walking up the trail from the direction of our campsite the night before. Incredulous, we exchanged a few rapid words before I set off at a pace that would ensure I wouldn't actually lose said temper.

Walking alone for forty minutes did me some good and when I reached the start of the descent down to Boucher I had a sit to wait for Sandy, for I knew that descents, particularly with still-wobbly legs, made her nervous. When she arrived ten minutes later all was back to normal and we began the short descent to the drainage, where I waited another twenty minutes for her to come down. Her legs were tired and sore and her balance was gone, which meant that everything was taking twice as long for her as for me. After a brief hike up the creek, we returned to our first night's campsite where Sandy quickly fell asleep.

It wasn't like we had a terribly hard schedule to keep. Once starting out, we'd be at White's Butte in less than two hours, even at a slow pace and with a copious rest break. I amused myself for a while with lunch and photography, trying to give her as much time to rest before starting up to White's Butte. An hour and half, I hoped, would recharge her.

She awoke from her nap cheery as ever. The prospect of hauling water up to White's Butte for the dry camp didn't daunt her, as we were going back over known ground. With the prospect of the unknown removed from our trip, she could relax again. Indeed, she was all smiles as we set off for the climb that had broken three of my friends back in 2003.

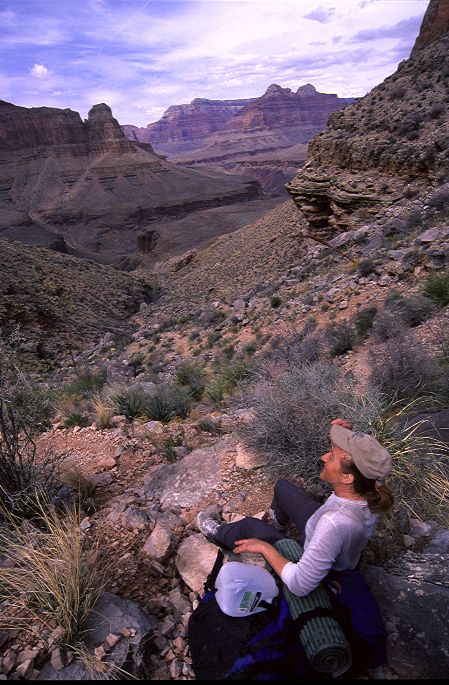

Sandy moved well along the trail, taking less time to go up it than it had taken her to go down in a few days ago. As we gained elevation we kept looking back on our route, amazed at how fast the land below shrunk to miniature scale.

Nearing the top of the climb we met the brushy chute area which slowed our progress a bit as the trail was no longer clear, but had bit of boulder strewn throughout.

Passing the cliffs below, I knew that we were within a few meters of the top and so refused Sandy the break she wanted in order that we might rest at the top, knowing for certain that our climb was over. White's Butte, which looks impressive from below, was a mere rumble heap from our vantage point. I had camped here in 2003 in the midst of a powerful wind and rain storm, something I wished to avoid this year. To the north and west the sky was clear blue with a few big white puffies hanging about. To the south and east there were large, dark grey storm clouds. As it was barely 3 pm, we decided to defer setting up camp to give the weather a chance to sort itself out and declare its intentions for the evening.

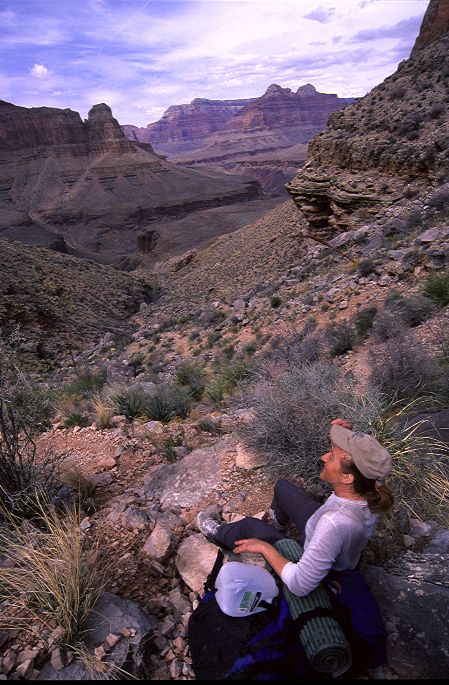

Sandy was thrilled to be on top, but wanted to gaze down at the world we had come from for a while. Understanding this desire, I let her be by herself and set out to roam about the plateau with my camera looking for interesting things to record. But really, I was simply trying to forget about the retreat and keep my heart as happy as I could.

I still had time left before starting teaching once again and I pondered how I might spend it. Unfortunately, I didn't really have enough time for another overnight backpacking trip in the canyon or along the drive back home. I could stop in for some car camping and day hiking in some of the desert parks, but I suspected that once I got to my car the desire would vanish.

I needed to be free for a while, and this need was only partly fulfilled by the walk down to Slate and back up. I needed time, I needed to be off a schedule, in order to be free and my time was running out. Best just to head back and try to live at peace with myself for a while.

After an hour I found Sandy perched on an overlook above the chute, gazing away, entranced by the beauty of the place and the satisfaction of doing something that she clearly recognized was at the limit of her current abilities. As the weather looked worse than before, we decided to spend another night under some cliffs, well out of the wind and mostly protected from any rain that might fall. The open top would be more scenic, but the memories of the storm in 2003 were not especially pleasant.

After eating dinner and chatting, we heard voices in the chute and around 7 pm the two backpackers emerged from the climb, sweaty and tired. They had lingered for hours in Boucher, though doing what I didn't ask. As we already filled out the cliffs, they left to camp on top and brave whatever the night might bring. The sun dropped and the world became black as I finished off the rest of my rum and cookies. No stars could be had, no moon seen. The night was just black, expressionless, almost hopeless. Sandy went to sleep with a cheer in her voice, repeating the words she had said to me so often over the last few days: "This was just what I needed."

A few drops of rain had fallen overnight and the air temperature was noticeably cooler than when we went to sleep yesterday evening. Clouds looked ominous and there was something of a wind, though for now the weather was holding. It was time to go, for we had a bit of a tricky climb coming up. The climb up and out of Travertine Canyon wasn't especially difficult, but there was the one spot we had to downclimb on our descent, and I didn't want Sandy to be doing this in the rain. I was worried about the weather, but Sandy, showing some green-ness, proclaimed herself to be thrilled by the clouds, so that the climb up wouldn't be too hot. Given that, at this time of the year, hot would be about 70 degrees, I almost laughed. Better to have plenty of sun and no clouds than to be rained and stormed on. I tried not to be annoyed.

I let Sandy lead the way out of our campsite so that we would not get too separated during the rough section of trail ahead. Moving slowly, with lots of rest breaks, we picked our way up the trail, climbing over the boulder obstructions without issue, and reached the top where a group (or perhaps several) of backpackers were beginning their descent.

I smelled the air and looked about, knowing that rain was on its way rather shortly. Needing a rest at the top, I found a sheltered cove for us to rest in, but Sandy, not thinking the rain was coming, chose a more open spot. As the rain came all I could do was shake my head. It was an honest storm coming down on us, not a minor drizzle. Given that the trail was now well marked, obstruction free, and that she had a map, I didn't think it too much of an issue to set out on my own pace, wanting to be out of the storm as quickly as possible. Sandy did want me to wait at the upcoming trail junction so that she would not get lost. Again, given that she had a map, had come this way before, and that there was a big, huge sign proclaiming the proper way, I again nearly lost my temper before blazing away. The wind picked up to gale force strength at time, the rain pounded down, and I again thought about her cheer at seeing clouds in the morning.

Pushing hard, I reached the trail junction at forty five minutes, rather wet and cold, and plopped down in the partial shelter of a juniper tree to wait for Sandy. I didn't know how long I could be sedentary before hypothermia became a risk, neither did I want to put on warm dry clothes to keep it away. I had to sit and wait for as long as I could. Thirty minutes later, she arrived, I hopped up, pointed at the right direction down the trail, and set off at a furious pace to rewarm my now-cold body. I was wet inside and out, but didn't care as I knew I could force the top quickly and get to somewhere dry and warm. Passing day hikers on their way down into the storm, I thundered up the trail and a pace that was about as fast as I could go. Climbing hard, I reached the top and went straight to the curio shop for tourists that sits at the end of the Hermit's Rest road.

Shivering now that there was no more elevation to gain, I reached the shop and tore open my pack in search of dry clothes. The well dressed tourists initially thought this funny, but when stripped down to my skin to get off the wet clothing, they seemed rather revolted at my bare body in a pubic place. Warm once again, I sat about waiting for Sandy, chatting with a few of the more adventurous tourists, including some very nice ones, before Sandy showed up an hour later, grinning and happy that she had come through ok.

A short ride on the heated shuttle bus, filled with a few chatty tourists who were happy that they had been able to "do" the Grand Canyon in the morning before the storm came in, was another exercise in patience. I was rather happy to get off the bus and race back to our cars, through the rain, and I am quite sure the tourists were just as happy to be rid of our smelly bodies, offending their delicate noses. I didn't want to think about a summary of our trip. Sandy was, as usual, happy as we set off in our vehicles, no longer hikers, in search of beer and a warm place to stay in Tusayan. These we would find, and much more, in the town. But those adventures are for another time and place to be told, and certainly not to the general public.