Road's End to Bishop

July 12, 2006

My watch read 6 am. Today. This day. Now. At the beginning of a long walk, the mind has difficulty comprehending how it ever thought such a thing was a good idea in the first place. It has a hard time remembering the pleasant evenings, when the body was curled up on a futon pouring over maps and descriptions of remote places, calmly drinking a beer, with Bach or Burning Spear playing in the background. Complete comfort has a way of making long, hard trips in remote places seem fun and adventurous, but when the time comes to actually do the walk, the mind revolts. A fickle thing, the mind.

I pulled myself out of my sleeping bag and into the warm morning air, almost thankful that we'd be starting on trail this morning, even though it meant more than a vertical mile of elevation gain. Trail was safe and secure. By the afternoon, we'd be stepping off trail and into the wilds, where such things are not frequently found . Although I felt the normal trepidation, I was also excited to start the trip, to begin walking north through a land as special as the Sierra Nevada. In only a few minutes the three of us were packed and hopped into the truck of our neighbor for a ride to the trailhead. Because of the heat at such a low elevation, he preferred his day hikes to be early morning affairs, with the afternoons spent lounging by a river, perhaps fishing. A nice retirement, I thought.

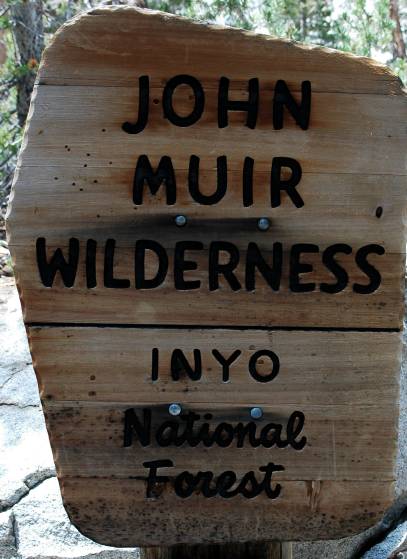

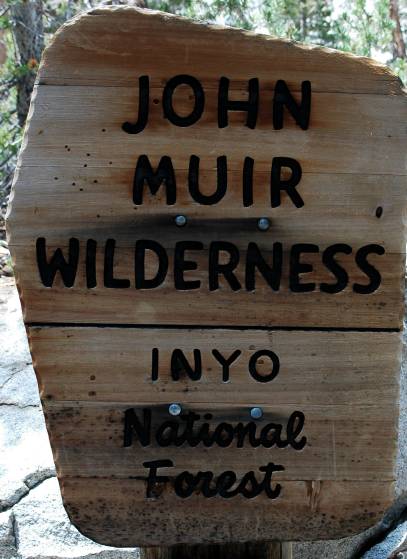

We were the only ones waiting for the rangers to arrive and issue us a permit, though a couple showed up a few minutes later. The idea of a permit for a hike such as ours bordered on the insane: We wouldn't be near trail for most of our hike. We had no idea where we would be camping. If we got into trouble, the length of our trip meant that no one would be coming to look for us. We would be passing through land managed by several different land agencies. At best, the permit would simply give the rangers some additional bodies to claim had passed through their land, bolstering their case for more funds when budget time came around. Perhaps we might help get a fancy outhouse built here at the ranger station.

An attractive young ranger opened shop for us and started the permit questions, though thankfully she recognized that we had some experience behind us and kept things short. I invented a few fictitious places where we might camp and stretched the truth a bit about our bear canisters. Sure, we each had one. Two Bearvaults and one Garcia. Of course the Bearvaults have the red sticker and the button. Yup, all of our food and smell-ables are inside. The ranger hadn't issued a permit for the Copper Creek Trail in ten days and warned of serious snow above 10,000 feet. She wished us well on our hike and sent us on our way with the permit in hand. We were now legal. At least we were as long as no one noticed that we had neither red sticker nor buttons on the Bearvaults, or that half of our food was in stuff sacks.

The depth of the canyon of the South Fork of the Kings River meant that we started our vertical mile in the shade, though quickly we pulled out and into the sun as the switchbacked trail snaked its way up the north wall of the canyon. Being on trail meant that we could move at our own paces and I had ample opportunity to walk and think. Walking is good for thinking, though I found most of my thoughts roaming over my life at home and the last summer. I was happy with my home life, happy with what I had been able to do there after I returned from my attempt on the Continental Divide Trail and all the misery I experienced then. The pale light bathed me as it came over the mountains, washing the valley clean. That same valley that was rapidly shrinking in perspective.

I climbed for 90 minutes in solitude before resting and drinking water. I was back. The first sip of mountain water, unspoiled by chemicals, drunk from the source without treatment, is one of the signs. Another is the calmness. I sat only a few minutes before pushing higher, my sweat having not had much of a chance to dry from my face. After thirty minutes I stopped at Lower Tent Meadows and another stream to wait for Birdie and Ishmael. Although we were still several thousand feet from the crest and the beginning of our off trail travel, I did not want huge distances between us as we went higher and higher. I rested for an hour, luxuriating in the lap of freetime. I found my head still drifting back to Puget Sound and the life that I had managed to build for myself there. I was comfortable and happy there, with new horizons, new opportunities, new people appearing everyday. And so I also questioned why I was where I was. Why leave such things for three weeks of living at Nature's whim? Why, indeed.

Birdie and Ishmael came up the trail and rested for bit before we began climbing once again. The boots on Birdie's feet were causing her problems, as her normal foot coverings were trail runners. I, too, was in boots, but after a winter and spring of climbing in heavy mountaineering boots, the light fabric models seemed like slippers in comparison. Both Birdie and Ishmael had heavier than normal packs due to the amount of food and the bear canisters. After hauling 50 lbs up and down glaciers, my pack seemed light. The process of moving uphill seemed a joy, especially on the solid trail and thoughts of the upcoming trail-less segment vanished as we began to approach tree-line. Mount Clarence King and the other high peaks of the southern and eastern Sierra vaulted up on the other side of the deep gorge we had just climbed out of. For now, my question of Why seemed stupid and obvious. A beautiful place and a well designed trail can do that for a hiker. One gains a sense of living in the complete present, without worries of the future or the burdens of the past. A monk in Thailand had told me that after letting go of the past, that after releasing the future, I would have to relinquish my grasp on the present. With all attachments severed, the cycle of suffering that is Life would end. I couldn't see that happening at this particular moment.

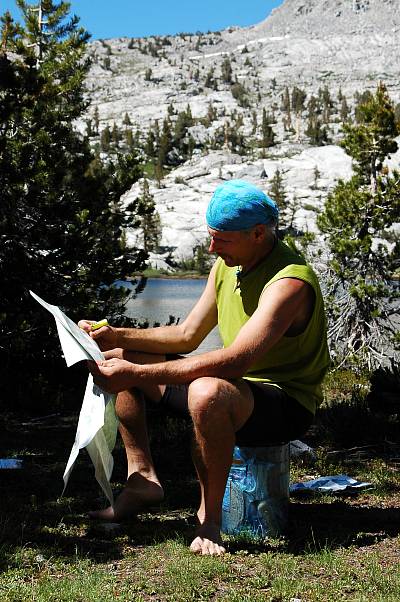

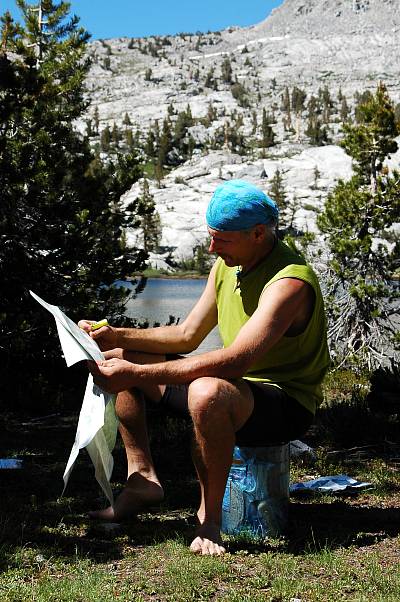

The trail leveled off as we broke the 10,000 foot mark. Only a few minor patches of snow dotted the thin forest at the crest, and the view to the north showed only slightly more. Apparently, the information concerning thick snow at this elevation were slightly outdated. To the north held the path of my first trip in Kings Canyon, far back in 2001. It hardly seemed possible for only five years to have passed since then. I wasn't five years older. I was a different person. We rested for a while, scanning maps and the route description, for we would shortly be leaving the trail and moving cross country through the forest to Grouse Lake. No obstacles, just contour. The High Route was starting off easy.

The forest was open enough to make walking through it easy: No bushwhacking, no Devil's Club, no monster creek fords. Grouse Lake was a scant half mile away, approaching on a contour, with some slight uphill walking along blindingly white slabs of granite. Walking on the slabs was about as difficult as walking down a paved sidewalk in town, though much more aesthetically pleasing.

The shore of Grouse Lake was inviting. An extended rest and a hot lunch were called for after our nearly 6000 foot climb. The first pass of the trip was visible above the lake's far shore and looked very easy. Shade and a pleasant breeze coupled with a patch of soft, green grass gave the basin a feeling of comfort and luxury that no high-end restaurant could hope to replicate. Stoves were fired up and meals prepared along the lakeshore only after, of course, boots and socks were removed and sleeping pads spread out for that extra touch of fine living. The fact that there were no mosquitoes shocked and surprised us, but no one complained.

Although Grouse Lake would have made for an excellent camp, all of us were anxious to get up and over the first pass and there was still a lot of daylight left. We picked our way along the boulders of the lakeshore, moving steadily higher on a rising contour toward the pass. A few bits of firm snow interspersed with the white boulders and green grass that provided our route to the top. The lake fell away behind us, along with the deep gorge we had come from. It would be our last view of our start, a milestone that every traveler both celebrates and mourns.

From the pass a new world opened upon us, one unbroken by any semblance of a trail. Though I knew that others had been here before, the feeling of exploration was unshakable: There was no trail to guide us or restrict us. Goat Crest Saddle, our next pass was visible across the lakes basin below us. Snow and rock dropped off mildly below the pass, though not so much as to make the descent difficult. After a long rest, we decided to hunt down some hidden lakes and camp for the night, rather than trying to get up and over the pass and down to camping on the other side. The basin was pleasant and we had worked our bodies to get here. A short day was in order.

We scooted down the soft snow, taking to rock from time to time, and arrived at the large stream system running from lake to lake through the basin. It took only a few minutes for each of us to find our own way across this minor obstacle; Birdie and Ishmael rock hopping, myself leaping. The route back up to the pass looked just as easy and pleasant as the ascent on the other side had been, and I hoped that all the passes on the High Route would be as civilized as this one was. I hoped, but having read ahead in the route description I knew that this hope was delusional at best.

We picked our way up toward the hidden lakes, though pulled up short of them at a flat, dry area sheltered between several large granite slabs, amply watered by a stream close by. Home. With much daylight remaining, I had a rare opportunity to write in my journal. Last summer I had taken to writing for several hours every day, pouring out my thoughts and feelings in an attempt, eventually successful, to sort out my life. I had stopped writing in October, with only a few entries in the winter and spring when life became confusing. It wasn't so much lack of time as it was lack of inspiration. It was hard to lack inspiration as I watched the sun drop on the horizon and the granite began to glow. Ishmael had gone off to one of the lakes to write as well and Birdie had disappeared, off to do her own thing. When she returned I had about finished writing and we sat talking together, watching the light show. Birdie and I had shared much time on the Pacific Crest Trail during the summer of 2003, a foundational experience for me. My comfort with her was beyond the ability of many to comprehend, myself included at times. With the last bit of light rapidly escaping, Ishmael returned from the lake to don warm clothes and to eat a snack before the stars came out and signaled an end to the day. The trepidation that I had felt this morning had up and vanished. The present was the only thing of importance, it seemed. Again, the monk's challenge seemed an impossible one to achieve.

Dawn comes late to a mountain ringed basin. Although perfectly light at 6 am, the sun was still more than an hour away from striking us directly as we each rumbled through our morning routines. A half liter of green tea and a breakfast cookie for me, hot chocolate and pop tarts for Birdie. Ishmael seemed to prefer stretching to breakfasting. By 7:15 we were rolling up the basin heading for Goat Crest Saddle, a large, prominent pass at the head of the valley. Although it still held a lot of snow, the ascent of the pass was easy and pleasurable, passing by several small ponds that had partially frozen overnight. My heart rate never broke 70 on the climb up.

From the top of the pass we gazed out onto an entirely new world. Well below us, at the base of the saddle, sat lovely Glacier Lake. Large for its elevation, it seemed we had made a mistake in camping early in the basin, for a night at the lake looked wonderful indeed.

With the sunshine now direct, I quickly skinned off my thermal underwear, stripping down to shorts and a t-shirt, and dabbed on large amounts of sunscreen. The descent down to Glacier Lake didn't look especially difficult, with low angle (perhaps up to 20 degrees in spots) snow separating islands and fingers of rock. Indeed, except for the initial traverse across steep snow to gain an expanse of easy rock, the descent proved simple.

There was one obstacle that all of us had missed: Mosquitoes. After a day without them, I had convinced myself that somehow they did not exist in this fine land of granite. The mosquitoes didn't care at all what I had convinced myself of and began their attack before we even reached the lake. Swarming and biting, the buggers flew up my nose, in my ears, and, occasionally, down my throat, bringing forth choking fits as I moved down the snow, racing for a spot where I could douse myself in DEET.

Fully protected, the bugs declined to land on me, but hovered incessantly around my body, sure that there was something tasty to eat in the vicinity, but fooled by the DEET just enough to stay off of my skin. We moved around the upper lake and descended slowly, but surely, through the thin forest to another of the Glacier Lakes, and eventually to the top of a cliff where we had some protection, courtesy of a breeze, from the bugs and a nice view of our route for the latter part of the morning. A long, green valley stretched below us, leading to a trail junction that we would take up and to the right to get up to the next set of lakes and yet another pass. Simple! We'd been moving well without a trail, so once we found that trail (which we would have to cross) our progress would be rapid.

A short bit of rock scrambling got us down from the cliffs and into the valley, where the bugs alternated between ferocious and placid, depending on our proximity to swampy areas of the valley. A use trail ran alongside of the open part of the valley, winding into the forest from time to time, fading in and out. It didn't really matter, for there was only one direction to go. Unfortunately for us, the trail we were looking for never appeared. After an hour of hiking down the valley, we reached a sharp bend in the river and, after consulting the map, realized that somehow all three of us had stepped over the trail without realizing it. Rather than retreating and searching, we forded the river and set out cross country through the woods, bobbing and weaving as the terrain dictated, but generally trying to head northeast. After an hour of (mostly) pleasant walking, I spotted a trail to everyone's delight.

After a lengthy lunch and foot drying session, we followed the trail to a nice set of lakes. However, a quick look at the map showed us that we should not have run into a nice set of lakes: We were going the wrong direction yet again. We retreated back a mile and followed the trail in the opposite direction, winding in and out to reach the Horseshoe Lakes several miles later on. The heat of the day was full on and my body began to tell me something: Drink more water, you lackwit! With the route finding difficulties of the morning, I hadn't bothered to drink as much water as I should have and needed a good break to do so. We agreed to meet at the largest of the Horseshoe Lakes, where we would again step off trail. Ishmael and I found a lake with a resident bald eagle and had a sit. When Birdie didn't show after a few minutes, I quickly looked over my map and found that we were not sitting at the largest of the lakes. Denied the needed water by my own incompetence, I quickly packed back up and rumbled up a hillside to look for Birdie, eventually following her calls to the other side of the proper lake.

Making yet another mistake, I left the lake without getting water, without drinking the little that I had in my pack, and without the rest that I wanted. I was sure there would be a pleasant stream somewhere close by, but unfortunately there was only a steep, sunny, hillside that seemed to delight in having an immense collection of dust piles. When your body runs out of water, physical activity becomes unpleasant at best, difficult normally, and at times it makes walking impossible. With no energy, no desire, a headache, and a sour stomach, I pulled my way up the hillside for several hundred vertical feet until we, at last, came upon a nice finger of water running out to a spectacular view of the deep valley below us.

I gathered 2.5 liters of water out of the stream and collapsed in a dust heap that was nicely shaded by a large bush. As the water flowed into my body, I began to feel better and better, with the sour stomach vanishing and my energy and drive returning. A thirty minute rest brought me back to normal, with a desire to tackle the easy route ahead. The description didn't sound too bad, with plenty of large landmarks to navigate by, and that reassured me after our route finding difficulties of the morning and early afternoon.

However, they were not over. After skirting by some pretty lakes and picking up segments of an old use trail, we missed all of our obvious landmarks. No worries, I thought. Ishmael and I spotted what we thought was Windy Pass, well above us but quite clear. Never-you-mind that the ascent to the pass didn't even remotely match the route description, which involved descending. We know the right way. And so off we marched, heading higher on rock and occasional snow. Forty minutes later I reached the pass and gazed down a sheer precipice.

Far, far below us lay the basin we needed to be in. Separating us from it was a long rappel and very, very steep snow. As we had neither rope nor harnesses, our progress was ended. Frustrated, I let out a yell and threw my arms up as the others finished the ascent. There wasn't any doubt now: Our pass was not the promised one. We were far too high. After scanning the map, our error became clear and, looking down from where we had came from, the true location of Windy Pass was about as obvious as a set of wings on a pig. All three of us were tired and weary from the numerous route finding mistakes we had made this day and so, after a short descent to water, we decided to rest and eat a hot meal. Passing most of the hour in silence, despite the unbelievable views of the brutal mountains around us, I tried not to focus on the route or our mistakes.

Although the land was stunning, much different from the Cascades and Olympics, my attention was now directly completely on finding the correct route down and into the basin, and then up to White Pass. Leading down snow and rock, the beautiful world passed by almost unnoticed. I had experienced this before on the Devil's Backbone in Montana: A special place ignored because other thoughts, other problems were keeping my attention from it.

I was no longer a part of the natural world. I was no longer moving in harmony. Rather, I was concentrating on merely getting through. I hated the feeling, the wasted time. But most of the day had been spent backtracking, misreading the map, misinterpreting the route description, and making poor choices. At the end of the day the last thing we needed was another problem. All I wanted was camp.

We made the descent into the basin and began to scamper up large granite slabs and boulders to the head of the valley. The steep walls of the valley and the later hour meant that we quickly entered into shade, yet the part of the valley below us was well lit by an intense white light. The basin held many small lakes and streams, and their attendant green grass and microwildflowers. An idyllic land. All I wanted was camp.

Moving hard and fast up the granite, I realized that Birdie and Ishmael were still well below me. Stopping periodically to keep them in sight, my camp drive intensified. I tried to assuage it by taking photographs and pondering the land, but these tactics failed. All I wanted was camp.

I finally reached the top of the basin, directly underneath White Pass, and waited for fifteen minutes as the others made their way up the slabs and boulders. The head of the valley was beautiful in a stark way, with few features other than rock, patches of snow, and flowing water. Nothing green. The outlet stream from a large lake ran though the region, but we declined to follow it to the source. Instead, just past a pile of scat, most likely from some large cat, we found a flat sandy area and threw up our respective homes for the night.

The ascent up the basin had taken me through an amazing land of spectacular austerity, mixed with explosions of green around the numerous water sources. But all I had wanted was to get into camp. My photographs would record the sights, but could never capture the spirit of the place, its true essence. You had to pass through it, to spend time in it, to truly appreciate a land like this. My body had passed through, but my head was somewhere else and I had missed the place. Safe and warm in my sleeping bag, I wasn't even remotely bothered by this.

I felt much better in the morning and was ready to tackle the passes once again. We simply needed to be more careful, to pay more attention to the route and not just follow our noses in a blind fashion. The basin we had camped in was just below White Pass, though our experiences from yesterday meant that we spent a long time looking at our various maps and reading, and re-reading the description of White Pass. Granite ramps and grassy slopes gained us most of the elevation to the pass, which finally showed itself. A long traverse of hard frozen snow slowed us significantly, however, and I had to cut a few steps en-route in the slippery early morning concrete. The view from the pass was substantial, with the usual mile-after-mile of rugged, imposing mountains in the background, and a pleasant, though barren, lake basin below us.

The location of Red Pass was immediately clear, sitting next to a minor peak with a large red streak on its flanks. Relieved that we had an easy, obvious route ahead of us, I sat for a break in the sun and the ritual exchange of thermal underwear for sunscreen. Leaving the pass, we traversed up and along a sequence of rocky ledges until reaching snow that was safe to traverse.

The snow was perfect to walk on and gave us a route as easy as a trail all the way to the pass. I had been playing on snow slopes for most of the winter, spring, and early summer in Washington and found the route quick, though the extensively sun-cupped snow meant that glissading was not a wise idea.

From Red Pass I gazed down into the deep cirque holding Marion Lake, colored an intense, preternatural blue, and beyond it to the Lakes Basin where we had to head. Somewhere in the Lakes Basin was Frozen Lake Pass, whose description in the book had been spooking me for months. The route finding to the pass was supposed to be difficult, with the pass not visible until you were almost upon it, and the pass itself was supposed to be rather dangerous, with lots of loose talus. A warning about leg-crushing was given by Roper.

We re-grouped and I led out onto the much steeper snow heading down toward Marion Lake, taking to rock where appropriate. The steepness of the snow slowed Birdie and Ishmael significantly, and I found myself all alone at a pleasant lake and a steep cliff above Marion Lake.

Marion was a true gem of a lake and very unlike many of the previous lakes we had passed by. Instead of being barren and rock bound, Marion was lush and verdant, inviting rather than intimidating. Marion was a place of leisure and relaxation, though reaching it seemed to be something of a problem. Several steep gullies led through the cliff and down to the shore, but none seemed especially civilized.

As per the route description, we chose one on the far left of the cliff system and began the delicate descent. Birdie and Ishmael took to the loose rock and scree on the right of the gully, while I hopped on the snow, feeling more secure there where the footing was a little more assured. After twenty feet of easy going on the snow, I managed to slip and had to self arrest quickly. Already wet from the snow, I glissaded the rest of the way down toward the lake and then crossed over to pick up the use-trail that the others had found.

The use trail led comfortably around Marion Lake to near its outlet, where we paused for water and a rest in the sun. The gully we had come down seemed preposterous from this perspective, but we had managed it safely. However, the "easy" gully described in the book was sitting even further to the left of the cliff system and really did look simple.

The lake was too inviting for Ishmael, who quickly stripped down and dove in, letting loose a series of loud howls from the chill water. Although beautiful to look at, Marion was not about to let anyone swim in her for very long.

After his swim we packed up and headed cross country for the Lakes Basin and Frozen Lake Pass. We had been scanning for the general location of the pass from the very beginning, but we still moderately confused as to its location. As we climbed into the basin, and the trees began to thin, the big, massive pass that we had hoped for, to the left of a prominent pyramid, began to become less and less likely. Instead of the easy pass, it looked like we needed to go over the hidden pass to the right of the pyramid. Not a pleasant prospect, especially as we couldn't see terribly much of it. While the massive pass would be easy, it would drop us into a basin and we'd have to go over yet another pass to get into the basin below Mather pass.

We found a nice spot with running water for lunch and sat for an hour in near silence. Whether because of the focus on eating or the worries about the pass, very few words were exchanged. After a final bit of map reading, we set out for the pass, crossing many outlet streams and passing by their lakes. The Lakes Basin was about as beautiful as a place as Nature is capable of producing, but I was concentrating more on the pass and the route than on the scenic qualities of the land.

This, perhaps, is the greatest downside to off trail hiking. The uncertainty of getting through becomes very distracting. With a solid trail, I am more aware of my surroundings and my place in them. Without a trail, I have a problem to work on and notice less.

Picking up the outflow stream of several large lakes that our map told us sat just below the pass, we began scrambling up the easy class 2 and 3 rock toward the lakes themselves, which were still out of sight. I kept hoping that an easy pass would appear, but as I went higher the pass began to look worse and worse.

The pyramid to the left of the pass was a loose choss heap, which is a technical term for a place where you don't want to go. The remoteness of the place struck me for the first time, as I realized that if any of us got hurt, it would take at least two hard days of hiking for someone to get out to a road to get help. If the injury was at all serious, the victim could be in a lot of trouble. A slip and a fall, or rock fall from above, could produce a compound fracture with some ease. Four or five days might mean an infection and a loss of the limb. Or life.

Ishmael and I topped out on the rock pile we had been climbing and gazed down upon one of the large lakes our map said should be there. I set off for a high, rocky point in the hope of finding the final lake and to get a good view of Frozen Lake Pass. I kept hoping to see a solid route, or good snow, leading up to it, but knew that this was a futile hope. Indeed, upon reaching the point I saw the final lake and the pass, losing all hope. My mind now turned to survival rather than enjoyment. The start didn't look too bad: Careful talus hopping with a little snow, but extreme care would have to be exercised on the loos rock above. I let out a yell and sat, dejected, on a warm rock to wait for the others.

There was nowhere else to go, however. The three of us re-grouped and scanned for a route to the top. Thankfully, Ishmael cheerily agreed to lead the pass. I had no desire to go over the pass, let alone be responsible for picking a safe path. The individual skills of the members of our group, that had been showing themselves for the last few days, became bloody apparent on Frozen Lake Pass.

We traversed across bits of snow that separated the talus field below the pass. Moving slowly on the rock, we gained little elevation at first, but then moved rapidly rapidly upward as we neared the pass. While most of the talus was stable enough to be relied upon, this wasn't always the case. The Lakes Basin we had moved through a few hours earlier began to fall away at my feet, but I couldn't even remotely appreciate the views: Each step was measured, every rock scanned. Occasionally a rock would roll about as I weighted it, though never especially seriously. Tired and lathered in sweat, I could no longer see Ishmael, though the route he had chosen was obvious at this point: I went the easiest way possible. After several slips in loose scree, I arrived the wall of the pass and a reasonable use trail led up it to the top.

Exhausted, both physically and mentally, I collapsed at the narrow pass to simply breathe. I didn't want to look at the north side of the pass, which was supposed to be the difficult and dangerous side, according to Roper. Birdie arrived, smiling as always, and had a seat as well. I was amazed at the calmness and composure of the others.

Nearly ten minutes had passed before I could stand again and take a few photos from the top, including looking down the north side. Far below was the frozen lake that gave the pass its name, and below that was the massive basin holding Mather Pass and the Pacific Crest Trail. The descent was going to be steep and on loose scree most of the way, but there was a thick blanket of snow as well. The steepness of it, approaching forty degrees near the top, along with the rocky run out, made the rock route mandatory at the start.

We had to get off the pass. No one else was going to do it for us and there was no easy way to go. We simply had to do it as safely as we could. Ishmael led down the scree and I gave him a long, healthy lead before following. Birdie followed me at a similar distance as we slowly picked out way down the unstable rock, launching bits downward despite our care. After fifty vertical feet, I couldn't take the steep, loose scree anymore and moved over to my friend, the snow.

Although much steeper than I would have liked, I could get a solid foot hold and belay myself with my ice axe as insurance against a slip. The route down through the snow had to dodge numerous rocks, but I felt much safer here than on the rock, which Ishmael was still on. Again, individual strengths dictated our specific routes, but all three of us made it off of the very steep part and down to Frozen Lake safely.

Another steep cliff separated us from the nice, flat basin below us, but fortunately its left side was thickly covered in snow and the descent of the snow field seemed trivial in comparison to what we had just done. The day, however, was getting long and we were all tired. I was weary of moving and simply wanted to eat dinner and camp for the night. But the Pacific Crest Trail was close and the prospect of again standing on solid trail provided just enough drive for us to keep going. Looking back at Frozen Lake Pass, I could hardly believe that we had just descended it without breaking a bone or four. No amount of money could have made me try the pass from this side.

After rounding yet another cliff system, we hiked across the mostly flat basin searching for the PCT, finding it after almost an hour. All three of us dropped to the ground and began a well deserved rest and dinner. Although spent, I could feel energy returning to me as I sat in the sun eating pasta, drying my feet and trying not to look at Frozen Lake Pass. Over dinner I began to question my commitment to the rest of the hike. I felt that we had gotten safely over the pass with some measure of luck. Although we had been very careful, a foot put in the wrong place, or a dislodged rock from above would have been very, very serious. I was far out of my comfort zone on Frozen Lake Pass and didn't want to push my luck much further. Although there was nothing especially dangerous sounding between us and our resupply at Bishop, there were some very gruesome passes afterward.

It was after 7 by the time we started hiking again, though we didn't plan to move very far. Just twenty minutes up the trail, far enough to get away from our cooksite. The sun had already moved behind the mountains and the shade, on my still sweat-soaked body, produced a chill that I was able to battle off only by dint of moving.

We found a dry, flat area next to a large snow field and quickly set up camp. The day had begun easily, but had ended hard. The glowing mountains in the distance and the reunion with the PCT could only do so much for my spirits. In a land of so much beauty, I found my mind stuck on one idea: Just hike the PCT north. Leave the High Route for someone else to try. The remoteness of the land and the last pass had driven fear into my mind, a fear that I didn't think would fade overnight. As travelers on the Oregon Trail used to say, I had seen the elephant.

As usual, I felt much better in the morning, body refreshed and mind empty of doubts. I still had no desire to go over a pass like Frozen Lake again, but I wasn't brooding on the future. For the next few miles we had the Pacific Crest Trail under our feet and Mather Pass looked substantially easier than when I had passed through three years ago.

In 2003 the pass had been completely snow covered and the route I took to the top was a steep, scary snow climb. Today there was only a little snow obscuring some of the well built trail and, although frozen hard, these sections were easy to traverse.

I reached the top without much effort and gazed out with something approximating joy, an emotion that had largely been replaced by fear over the last day. Everything was beautiful this morning, everything seemed possible. I had ten minutes on top before Ishmael and Birdie arrived, plenty of time to soak up the warm rays of the sun and get fully coated in sunscreen.

The others seemed to feel much as I did: The luxury of a trail was allowing us to more fully appreciate our surroundings, instead of worrying constantly about route finding and future difficulties. With a trail, there were no difficulties other than having to put forth a little physical effort. No technical problems. No scanning of maps. No parsing of a route description. Just move forward with a smile.

The north side of Mather Pass held more snow, but far less than in 2003, when I came through a full month earlier. Cirque Pass, the next one to be survived could be seen in the distance, hovering above where Lower Palisade Lake, still out of sight, sat.

Unfortunately for us, descending from Mather Pass was in no way as easy as the ascent. The north side of the pass was thickly covered in snow and that snow was still in the shade. Hard as concrete and steep, it proved formidable. I led out on onto the snow, trying to follow some mostly melted out steps, and trying not to think about the fast slide down the slope into the rocks below. Falling was not an option. Cutting steps proved extremely difficult with the light axe I was carrying, nor could I get it in solidly to belay myself. Feeling very insecure, I decided to down climb on the sun cups, which provided more solid footing. Birdie and Ishmael felt more comfortable traversing and continued on the route, making a direct line for some rocks on the far side. The sun cups, though slow, felt very safe and I moved down the mountainside, face to the snow, with something approaching confidence. Occasionally I would look up to follow the others' progress, amazed that they hadn't fallen yet, but mostly I concentrated on reaching my own set of safe rocks. Thirty minutes of effort got me down and eventually along to the trail, where the others had been waiting for a few minutes, having made it across the terrifying traverse without a fall.

With good trail underneath us once again, we quickly hiked down to Upper Palisade Lake, where we had a fast ford and the first company since the Copper Creek Trail several days earlier. Two retired men were out for a section hike of the John Muir Trail, from Bishop down to Mount Whitney. They were worried about the snow, but we re-assured them that they would now have good steps to follow and that the snow would be plenty soft to be safe. After a long rest, we forded the creek and hiked down to Lower Palisade Lake, where we would once again leave trail.

Just past the outflow, we left trail and began climbing green slopes and rock benches, heading for a pass that we couldn't quite see. Ishmael led the way, picking a good route and stopping frequently for conferences and course corrections. A steep, class 2 rock scramble got us around a cliff system and up to a basin below the pass. Thankful for the sight, Cirque Pass did not appear to have any real objective hazards.

Looking back to a small lake we had passed, along with the Palisades and, far in the distance, Mather Pass, I felt once again the enormity of the land we were moving through. I once again felt confident in the route we were taking, in the land immediately in front of us, and doubts were vanishing as the distance from Frozen Lake Pass increased.

A few class 3 sections broke up the easy scramble to the top, ending on snow. A deep lake basin sat below us and, on the other, slightly below us, was our next objective: Potluck Pass. Although the route to the pass was obvious, the particulars of getting up to it seemed delicate. An extensive, monolithic cliff system guarded the upper reaches of the pass and finding a straightforward route past it seemed to be unlikely. But lunch was calling and a hungry belly has precedence over a doubtful mind.

We carefully picked our way down rock ledges until it was possible to gain snow of moderate incline, and then bombed down the white stuff to reach the outflow the lake. I cooked up a pot of instant mashed potatoes along with some dried vegetables and olive oil and tried not to think too much about the upcoming pass. The book had a very feasible sounding description in it, mentioning a hidden-from-below, class 2 ledge system that would take us all the way to the top.

The route to the top proved, after some minor route finding issues, to be fairly pleasant for most of the way. A scree field turned out to have a solid use trail through it and gained us most of the elevation to the base of the cliffs.

However, Roper's ledge system wasn't especially easy, nor was it class 2. I found Ishmael waiting at one particular move, a bit of balancing work with a lot of exposure. I took off my pack and worked my way up, finding it easier than expected, but very happy that the others were below spotting me. I hoisted up my pack, and then Birdie's, and the others followed without too much issue. Dodging around a bit, we were once again frustrated and presented with a short crack climb of about 8 vertical feet. While not especially dangerous, it was most definitely beyond the realm of scrambling. Although not as easy as hoped for, Potluck was actually a fun pass and the view of our route ahead encouraging.

The deep Palisade basin below us held snow and lakes, rock and scree, but the route across it to Knapsack Pass couldn't have looked easier from our vantage point. Even Knapsack Pass, several hundred feet below us, looked like a cakewalk. However, there was the little matter of actually walking over to it, a task that became progressively more difficult as we neared Upper Barrett Lake.

As we approached the lake, various rock outcroppings obscured our view of the lake and snow became thin enough that I continually broke through and down into streams and ponds below. We wound our way around as best as we could, climbing at last to a high ridge above the lake and pondered the rest of the route. It looked much easier and faster to round the lake on our side, but we could not see the outflow of the lake, which might be impassable. The other side of the lake would be a longer route, and harder, but we would not have to deal with the outflow.

We decided on the longer, sure route and were rewarded (for following Roper's route) with a sometimes-there, sometimes-not use trail. The massive Palisades loomed above us, looking preposterously difficult as a climb, but very pretty as a bit of scenery.

We climbed a bit, passing by another stunning lake, and pondered going over Knapsack Pass tonight. From our vantage point, it looked easier than anything we had done since the first day of the hike. Roper described it as easy as well, though he declined to give specific directions for it, instead simply saying that many routes were possible. However, we had information from another set of hikers who had done the SHR the year before and found Knapsack to be impossibly difficult. Their descriptions of the other passes had been accurate, thus confounding us.

The day was well advanced and we were tired as usual and so we decided to camp just below the pass in a flat, sandy spot with an awesome view of the lower reaches of Palisade Basin. The absence of bugs made this quick and easy: Throw out a ground cloth, unroll sleeping bag. Cowboy camping gives you the stars for a ceiling, a feature noticeably lacking under a tarp or in a tent.

The sunset in the basin was spectacular once again. The basin filled with light of a quality not to be had in a settled land, but the real treat was still to come. Once the show in the basin was over, the hulking Palisades, looming over our camp, began to glow well after the sun had set behind Knapsack Pass. Their height meant that while we were in rapidly increasing darkness, their faces began to glow pink, then orange, and finally red. A very nice reward for our sloth.

My stomach was churning. The strong, black tea that I brewed up for breakfast didn't help matters at all and I was close to vomiting even before I crawled out of my sleeping bag. If Knapsack Pass was, in actuality, a difficult obstacle, I was not in the shape for it. We packed up and began moving before the sun had cleared the ridge, hoping for the best. The pass was only 200 feet above us and we quickly gained the top. No difficulties. There were lots of possible routes, but the one we took involved only a few class 2 boulder systems. The other hikers could not have gone over the same pass.

From the top of the pass we were afforded a magnificent view of Dusy Basin, one of the most popular destinations in the Sierra Nevada, with its many open lakes and stunning surrounding mountains. My stomach problems had vanished at the top of the pass. There was a trailhead about 15 miles away, which we were aiming to get to by the early afternoon so that we could hitch into town with plenty of time to enjoy all that Bishop had to offer. The basin was beautiful, but no more so than any of the other basins we had passed through. It was, however, rather welcoming given the fact that once we traversed across it, we'd hit solid trail once again.

The other hikers had described the descent as difficult and dangerous, but all we found was a gentle snow slope running all the way down to the first lake. This cemented our assertion that they had gone over the wrong pass. We hiked cross country along pleasant, lightly forested slopes, passing one lake after another, one waterfall after another, enjoying the thoroughly easy hiking.

A scant hour since leaving the pass, we arrived at a massively dug trail, complete with a set of stone stairs that must have taken a trail crew several hundred man-hours to construct. Perhaps a Boy Scout project, it was unclear why the stone steps were necessary, but it was hard to ignore the artistry and effort involved in their construction. With big trail ahead of us, we separated along the trail, each moving at their own pace, and headed toward Bishop Pass.

The lure of a town was powerful, but upon arriving at Bishop Pass my motivation for hiking just about vanished. The day was bright and warm, the scenery spectacular, and I most definitely did not feel like hiking down to a trailhead that would take us to the fiery flats of Bishop. Various hikers and backpackers came and went from the pass during the hour we spent lounging in the sun warmed rocks. As the town would not come to us, we would have to go to it. The heavily switchbacked trail quickly dropped us down toward the lakes region below the pass, though a few remaining snow tongues forced us to do a little scrambling along the way.

The lower we went, the thicker the traffic became. Fishermen, day hikers, even swimmers, were mixed in with the normal residents of a trail. The mosquitoes grew thicker as well and the air became hotter and hotter. At 8000 feet in Washington, you are going to be cold. At 8000 feet in the Sierra Nevada, you'll be roasting. We again strung out along the trail, each of us stopping to chat with people on their way out, trying to score a ride to Bishop.

One couple seemed willing, and so I raced after them to secure us a ride. I should have taken their rapid pace as a sign that they did not really want to jam three stinking hikers into their car for the thirty minute ride down to Bishop. After what seemed an eternity, I reached the car-filled parking lot just behind them. I dropped my pack and sat in the shade of a tree and watched as they quickly hopped in their car and drove off with a wave. I hoped that Birdie and Ishmael might have had better luck.

Ishmael rolled in a few minutes later with the good news that the large party we had passed earlier was willing to give us a ride down to Bishop. They were a Sierra Club party from Orange County, just out of the weekend on a short overnighter into some of the lakes below Bishop Pass. When all were assembled, a former Fort Lewis Army Ranger packed Ishmael and I into his SUV and drove us down to town, Birdie riding with another member of the group. Chris, our driver, worked for the federal government as a lawyer on water resource issues and pollution and gave us some interesting information about the massive water use of industrial farms in the Central Valley. Hearing anything other than route issues or bowel problems was a real treat.

The parade of cars dropped us off in the middle of town near a few motels. With the windows rolled up and the air conditioning on, none of us were prepared for the blast of heat that greeted our arrival. A bank display across the street read 108. There would be no searching around town for the best deal or location. We walked straight to the Rodeway Inn and got a room for $70. The AC was turned on immediately. Almost as rapidly the room acquired that sour funk that can only be produced by three hikers and their shoes.

Every town stop is the same for long distance hikers. We want the same things everytime, usually in a well defined order, though some variation is allowed given the fact that there is only one shower per room. I went straight to the McDonalds across the street, returning with a double quarter pounder with cheese, a double cheese burger, and a jumbo sized strawberry shake. The injection of more than 2000 calories didn't seem to faze me, neither did the fact that I never eat at places like McDonalds when at home. I showered and dumped my dirty clothes into a pile for future laundering before sitting down in front of the television to find out what had been happening in the world. The news was not good. Israel was in full conflict with Hezbollah, apparently fighting over the kidnapping of two soldiers. Many people were going to die.

In the early evening we set out wearing our rain gear, which given the 100+ degree heat was not very pleasant, to do laundry and find some dinner. I became rather dehydrated on the ten minute walk to the Pizza Factory and promptly guzzled 2 liters of lemonade, bloating my stomach and keeping me from gorging as I had wished. Like any good long distance hiker, I picked up some quality Sierra Nevada beer from the gas station before returning to the comforts of air conditioning and a soft bed. More people were dying on TV.