Asphalt Approach

August 5, 2007

Why am I doing this? I'm going to die. I will fall off a mountain. I will tumble into a crevasse. A river will sweep me away. A bear will eat me. I should stay at home.

The floor of my apartment was littered with gear. Bags of food were strewn throughout the kitchen. I sat on my futon scratching my head. Scratching my beard. I scratched my head again. I was going to a place that I swore I would never go back to. Yet, here I was, with three weeks worth of food prepared and gear assembled, getting ready to do just that. Mike and Wallapak would be here soon to take me to Vancouver. I should do something. Instead I scratched my beard once more.

In 2001 I had first gone up north. Mike Bennett, John Grant, Kevin Burke, and myself had traversed across the Arctic Plateau, crossed the Spectrum Range, and then traversed the Edziza Plateau, moving from Arctic Lake to Buckley Lake. That was difficult, but enjoyable. In 2002, Mike, John, and I had gone back, this time flying in once again to Arctic Lake, but heading west, crossing Mess Creek, in an attempt to climb Mount Hickman. That trip was far more difficult and ended in a maze of crevasses, when we found that our food drop had been unsuccessful and after several crevasse falls. Mike and John returned three more times in the following years, while I pursued other interests, like hiking the Pacific Crest Trail, hiking the Appalachian Trail, traversing the Canadian Rockies, and moving to Washington and exploring the Cascade and Olympic Mountains that were now in my backyard. But now I was going back. As with any long journey, the idea is appealing until it comes time to actually leave home. Then the reality of what you are undertaking finally becomes immediate and slaps you in the face for your arrogance at thinking it possible. There is nothing to do at this point. I began stuffing gear and food into bags and packs.

August 7, 2007

Grayness. As Mike's Element sped out of Vancouver, I watched the faces stuck in their metal coffins making the morning commute from the suburbs into Vancouver along HWY 1. I wondered what they were thinking about as they moved along, sometimes as fast as 10 kilometers per hour. I thought about how safe their lives were, free from uncertainty. Predictable. Secure. Overloaded with gear and food, the Element lumbered out of town.

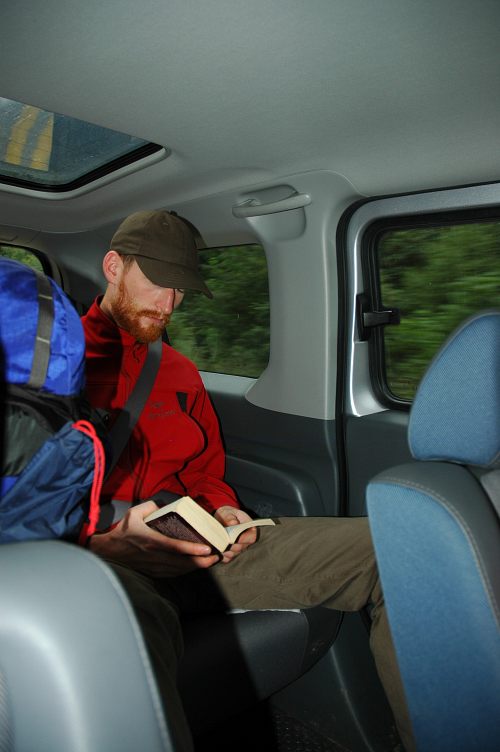

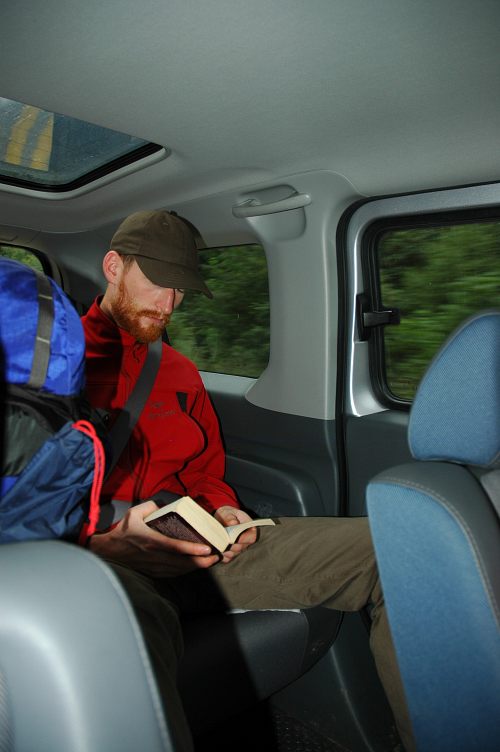

Mike, Bob, and I had spent a hectic day getting gear ready, buying more food, vacuum sealing dinners, preparing three 55 liter dry bags for an airdrop, and generally running around frantically trying to deal with things we should have dealt with long ago but hadn't. Whatever we didn't get done couldn't matter now, now that we were on the road. We breezed through Hope and turned north for the first time on the TransCanada, stopping only for coffee and pastries and to re-fuel.

At Cache Creek we left the TransCanada for HWY 97 and the run north. We swapped drivers and continued the weary drive. A town would pass by occasionally, usually nothing more than a couple of gas stations and perhaps a restaurant or two. 70 Mile House. 100 Mile House. The towns got smaller and farther appart. Lac la Hache. 150 Mile House. Williams Lake. At Williams Lake we descended into the Thompson River valley, in the rainnshadow of the Coast Mountains. The land became, almost immediately, arid. Looking more like California rather than British Columbia, this was one of the driest places in all of Canada and was home to many fruit orchards. The sun was shining and it was comfortably warm for us during the short breaks we would take to re-fuel. At Quesnel we left the Thompson and jogged north east before returning to a due north direction. Another driver change. At Hixon we re-united with the Thompson, but the aridness was gone. Now, the flat lands of British Columbia were in full force.

We raced into Prince George, the largest city north of Vancouver, large enough to have a branch campus of the University of British Columbia, and pulled over at a restaurant to have dinner with Bob's brother and sister-in-law. The road was tiring. The driving was monotonous. We supped and chatted for an hour before hitting the road once more, intent on making it another few hours north before stopping for the night. We left HWY 97 and rejoined HWY 1. Fewer and fewer towns. The distance between houses grew great as we left anything that might be called urban. Two hours brought us to Burns Lake and the end of our day of driving.

I was tired of thinking about the dangers that lay ahead and just wanted to face them, to engage them, to deal with them. There were so many unknowns, so many variables, that it was too much to try to organize. I couldn't think them away, so I settled instead on waterproofing the new boots that I was taking with me up north. Taking with me into the Stikine. We still had another day of driving to do, nearly a thousand kilometers, before we reached Tatogga Lake and our float plane. Even then, the weather might ground us for several days. And then I would begin to make shape out of the uncertain void that was the future.

The land passed by. We were far north now, after making a stop in Smithers for breakfast and to try to chase down a map that was supposed to have been delivered to us in Vancouver, but had failed to arrive. I won't bother trying to describe the interview that Mike and Bob had with an agent from Air Canada; the stupidity of that corporation is too well known. At Gitwanka we left the TransCanada again and jumped onto tiny HWY 37, also known as the Cassiar Connector, or the Alaska-Stewart Highway. This is one of the two routes to Alaska, though we would not be going quite that far, the other being the AlCan. There is almost nothing along the route except for a few scattered First Nation villages, and a lot of logging. And wilderness. The environment this far north is so harsh that few people live here. At Meziadin Junction we found the only gas station, which is also the only building, closed permanently and had to detour over to Stewart to buy gas for the final haul to Tatogga Lake. The small road to Stewart passes by a massive glacier spilling down to a lake. The lake used to be the glacier, but global warming had pushed the ice far enough back that a big lake sat where the glacier used to be.

And the drive continued. HWY 37 used to be only an "improved" road from Meziadin north to beyond the Yukon, but the Canadian government had been slowly replacing the hard packed gravel with pavement. The utility of this was dubious, but progress demands certain things, and paved roads are one of those things.

We drove north. And drove and drove. As we began to approach Tatogga Lake, signs of activity increased. An new airstrip was in place. People bustled about. It was because of the mine. The mine at Galore Creek that would eventually become the largest in North America. And we would be passing right by it. Construction of the mine and the road building to reach it from HWY 37 was bringing many jobs to the area and the jobs paid extremely well. In return for destroying a portion of their land, the people of the north got paychecks.

And still the Element pressed forward. We had seen more than 10 black bears on HWY 37 so far, but when we saw a mountain goat standing in the middle of the road, we were truly baffled. Mountain goats like high, remote areas, far from predators. But here was one in the road, far from any mountain and in the middle of a sea of predators, including black bears, grizzly bears, and wolves. And humans. The goat jumped into the brush and we sped past.

The road, it seemed, would never end. Ever northward, the road pushed us further and further from the safety of Vancouver and closer and closer to the dangers of the Scud. The size of British Columbia would put a Texan to shame. In that state you might spend a long day driving from Texarkana, in the east, to El Paso, in the west. We were nearing two days of driving, and when we stopped we would still be a few hundred kilometers south of the Yukon border.

We arrived in a light rain. It wasn't a city or a town or a village or a hamlet that ended our driving. Rather, it was a small lake with a "resort" on one side of it. The Tatogga Lake resort wasn't much more than a collection of rustic cabins, some completely mouse infested and rotting, others pleasant enough for a night, set on one shore of a lake big enough for float planes use as an airstrip.

The resort had recently been sold and was under new ownership since the last time Mike or I had been here. Gone were the unpleasant, but highly competent Bavarians. Now, there was a married couple who were trying to run everything themselves, and as a consequence got nothing done. With the number of mine and road workers in the area, their lack of hired help put such a strain on them that they brought a mother-in-law in to help. One more set of hands didn't do very much and it took 90 minutes for the hamburgers we ordered to actually make it out to us. I doubted they would be in business next year, and it wasn't clear that when we returned from our trip, if we returned, that they would still be in business.

After dining, we moved into one of the nicer cabins and sorted gear yet again. I sat on the porch in a cloud of black flies and drank a few cans of cheap beer, waiting for tomorrow. Waiting to start this thing. I was terrified of it, and the only way to extract myself from it was to do it. Or go home. And I couldn't go home now. I made an attempt to bring things into focus, but found only more questions. I drank another can of beer and waited for tomorrow.